Lewis Nkosi (5 December 1936 – 5 September 2010) was a South African writer and journalist, who spent 30 years in exile as a consequence of restrictions placed on him and his writing by the Suppression of Communism Act and the Publications and Entertainment Act passed in the 1950s and 1960s. A multifaceted personality, he attempted multiple genre for his writing, including literary criticism, poetry, drama, novels, short stories, essays, as well as journalism.

Lewis Nkosi | |

|---|---|

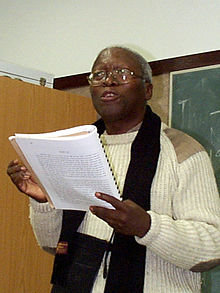

Nkosi at the Centre for the Study of Southern African Literature and Languages, University of Durban-Westville, 2001 | |

| Born | 5 December 1936 Embo, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa |

| Died | 5 September 2010 (aged 73) Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Nationality | South African |

| Occupation(s) | Novelist, journalist, essayist, poet |

| Notable work | Mating Birds (1986); Mandela's Ego (2006) |

Early life

editNkosi was born in a traditional Zulu family in a place called Embo in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. He attended local schools, before enrolling at M. L. Sultan Technical College in Durban.[1]

Later life

editNkosi in his early twenties began working as a journalist, first in Durban, joining the weekly publication Ilanga lase Natal ("Natal sun") in 1955, and then in Johannesburg for Drum magazine and as chief reporter for Drum's Sunday newspaper, the Golden City Post, from 1956 to 1960.[2]

Literary career in South Africa

editHe contributed essays to many magazines and newspapers. His essays criticised apartheid and the racist state, as a result of which the South African government banned his works.

Life as an exile

editNkosi faced severe restrictions on his writing due to the publishing regulations found in the Suppression of Communism Act and the Publications and Entertainment Act passed in the 1950s and 1960s. His works were banned under the Suppression of Communism Act,[3] and he faced severe restrictions as a writer. At the same time, he became the first black South African journalist to win a Nieman Fellowship from Harvard University to pursue his studies.[4] When he applied for permission to go to United States, Nkosi was granted a one-way exit permit to leave South Africa, thus being barred from returning. In 1961, accepting the scholarship to study at Harvard (1961–1962), he began a 30-year exile.

In 1962, he attended the African Writers Conference at Makerere University, along with the likes of Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong'o and Ezekiel Mphahlele.[5] Moving to London, Nkosi obtained work with the BBC and between 1962 and 1965 produced the radio programme Africa Abroad, also interviewing major African writers for the television series African Writers of Today on NET, and serving as literary editor for The New African magazine (1965–1968).[6] He appeared in Three Swings on a Pendulum, a programme about "Swinging London" in 1967, which can be viewed on BBC iplayer.[7]

In 1970, he was visiting Regents professor at the University of California-Irvine, and having earned a BA degree in English literature from the University of London (1974) and an MA from the University of Sussex (1977), he went on to become a Professor of English at the University of Wyoming (1991–91), as well as holding visiting teaching positions at universities in Zambia and in Warsaw, Poland.[6]

Return to South Africa

editLewis Nkosi returned to South Africa in 2001, after a gap of nearly four decades. His final years before his death in 2010 were passed in financial difficulties and ill health. He was apparently injured in a car crash in 2009 and spent his time on the bed, slowly recuperating from the wounds; however, a recovery never really happened and he drifted towards death. Despite Nkosi being considered an African literary legend, none of his efforts in literature gave him any economic relief and his friends and fans gathered a charity fund to pay his last medical bills.[8]

Nkosi died aged 73 on Sunday, 5 September 2010, at the Johannesburg Wellness Clinic.[9] survived by his partner, Astrid Starck-Adler, and his twin daughters, Joy and Louise.[10] A memorial service for Nkosi was held on 8 September at the Museum Africa, Newtown Cultural Precinct, in Johannesburg, and his funeral took place in Durban on 10 September.[11]

Works

editNovels

editThough Nkosi started his literary career in the 1960s, he entered the realm of fiction much later than his Drum colleagues. His first novel, Mating Birds, was published in 1986.[12] His next novel, Underground People, came out in 2002[13] and his third novel, Mandela's Ego, in 2006.[14]

Mating Birds (1986)

editMating Birds is the narration of an educated South African black native called Ndi Sibiya. He narrates the story from prison, awaiting a death sentence. As a jobless youth Sibiya wanders the city of Durban and reaches the segregated beach. There he finds a white girl on the other side of the fence (on the white side of the beach). They silently exchange looks and enter into a muted affair. They were well aware that race laws in South Africa would sentence them to imprisonment if caught. The white girl intentionally allows her naked body to be seen by Sibiya. He takes the entire episode as a love affair between the white girl and himself. The girl with her regular appearances on the beach and seeming interest dupes Sibiya into believing her.

After several silent meetings on the beach, Sibiya follows her to her bungalow, finds her lonely and willing, and enters into sexual copulation. But they are discovered by neighbours, and the white girl accuses Sibiya of rape. A trial by white judges begins. In the court, the white girl, Veronica, denies any knowledge of Sibiya and reiterates the charge of rape against him. The court finds Sibiya guilty and sentences him to death.

The novel generated a controversy and received critical attention, being awarded the Macmillan Silver Pen Prize in 1986. The New York Times declared the novel one of the best hundred books of 1986.

Underground People (2002)

editNkosi's second novel, Underground People, is a political thriller. In this novel, he moved away from the theme of inter-racial sexual relations and centred the story on the armed struggle in South Africa.

Cornelius Molapo is a language teacher and a member of the National Liberation Movement, an organisation waging armed war against the racist white minority government. He is a poet, a great orator, hungry reader of many books, and even plays cricket. He often criticises the policy of the Central Committee and irks its members. To counter him, they draw a strategy. The Central Committee of the Organization advises Cornelius to go to a remote part of the country called Tabanyane and to participate in peasant uprisings. The Central Committee plans to make use of his absence from mainstream life into an act of abduction by the Government. At first he hesitates, but reluctantly agrees. After reaching Tabanyane, Cornelius organises the poor illiterate jobless country men into revolutionary men and leads them. In this task, he enlists the support of Princess Madi, who is a daughter of the deposed chief of Tabanyane. During the clandestine operations, he takes two white hostages into his custody. However, he is unwilling to execute the unarmed civilians.

Meanwhile, the Central Committee starts a big propaganda about the disappearance of Cornelius from duties. They blame it on the South African police, who deny any knowledge of him. The National Liberation Movement brings the matter to international organisations including the United Nations and Human Rights International. The latter sends its official Anthony Ferguson, who was born in South Africa and immigrated to England, to investigate the matter. Anthony's sister and mother are still living in South Africa. After some rest he undertakes to search for Cornelius unsuccessfully.

The Central Committee members, plagued by jealousy of his success as a revolutionary, want to use the issue of white hostages for the release of their leader from prison, engage in talks with the Government and to observe a ceasefire. But contrary to the expectations of the Central Committee, Cornelius defies them and conducts attacks on the police stations and other locations. To escape police persecution, Cornelius leaves his hideout, and allows the white hostages to leave unharmed. The white hostages reach police and recognise Cornelius's photo and confirm his active presence in the fight.

Naturally, police suspect the intentions of Anthony Ferguson and ask him to go to Tabanyane, to convince Cornelius to surrender. He takes the help of a member of the Central Committee and reaches Tabanyane. However, Cornelius refuses to surrender and ditch the people for whom he had been fighting. Eventually, the police shoot, and he dies.

Mandela's Ego (2006)

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Nkosi's third novel, Mandela's Ego (2006), is the story of Dumisani Gumede, a teenage boy who has come of age in a Zulu village and runs after every girl and woman to satiate his newly acquired power. His uncle Simon tells him many stories about Nelson Mandela and makes him a follower of the great leader. Uncle Simon's storytelling is invested with lies and half-truths. He also tells Dumisani that Mandela is a great pursuer of women. Taking cue from the "real life" of Mandela, Dumisani goes unstopped in his conquests. In his village, every girl falls for his charms except Nobuhle, a beautiful orphaned girl. Dumisani's admiration for Mandela goes to the extent of starting a football club, with Dumisani as its chairman. He even goes to the city of Pietermartizburg to see Mandela, who comes there to address a convention demanding equal rights for all races and a dialogue among all the races.

After his schooling, Dumisani joins a tourist company as a guide. Dumisani's friend Sofa Sonke, driver of the tourist bus, brings every day a newspaper from Durban for him. After many attempts to win Nobuhle, Dumisani finally succeeds and gets accepted by her. She invites him to meet her on the river bank. On the same day, Dumisani receives the news of Mandela's arrest. The news shocks him and takes his nerve away. When Dumisani tries to unite with Nobuhle, his body fails. He tries again but his sexual energy deserts him. Nobuhle leaves in tears.

Dumisani consults many witch doctors, tribal doctors and conventional doctors in hospitals. But nothing works to cure him. He leaves his home, wanders the country aimlessly for years. When he reaches middle age, one day he hears the news of Mandela's release from prison. He attends the first public address of Mandela after the release. He rejoices. In his joy, he huddles a woman next to him, and his lost sexual urge returns. His life is restored.

Mandela's Ego was shortlisted for the 2007 Sunday Times Fiction Award.[5]

Drama

editNkosi's plays include The Black Psychiatrist and some drama for radio.[15]

Poetry

editNkosi's few poems include "To Herbert Dhlomo" in Ilanga lase Natal (22 October 1955). Ntongela Masilela notes that, despite Nkosi's early promise, "in his whole life he wrote seven poems, the last one written in Lusaka in the early 1980s where he was then living and published at that time in Sechaba, the political and cultural review of the African National Congress."[9]

Short stories

editNkosi wrote a good number of short stories. His story of police violence and popular resistance in a black township, "Under the Shadow of the Guns", appeared in the 1990 anthology Colours of a New Day, the book taking its title from an optimistic phrase used by one of the characters in Nkosi's story.[16]

Literary criticism and journalism

editHe wrote critical essays on many issues, including politics, history, African affairs, American culture, and civilisation. No other critic touches upon such diversified themes. His critical works include Home and Exile (1965), The Transplanted Heart (1975), and Tasks and Masks: Themes and Styles of African Literature (1981). His essays and other works were published over four decades in America, England and Africa. Publications in which his writing appeared include Drum, Ilanga lase Natal, Golden City Post, Transition, The Guardian, The Africa Report, Afro-Asian Writings, Sechaba, New Society, The Spectator, New Statesman, The Observer, Negro Digest, Black Orpheus, Fighting Talk, Contact, The African Guardian, Southern African Review of Books, London Review of Books, Genèva-Afrique, The New African, and Harvard Crimson.[9]

Themes

editAs opposed to apartheid, Nkosi's work explores themes of politics, relationships, and sexuality. His works, possessing great depth, received less recognition than they had actually deserved. In the post-apartheid era, his works are gaining critical attention across the third world. Nkosi joined forces with African powerhouse authors Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka in an interview in the third chapter of Bernth Lindfors' Conversations With Chinua Achebe. In 1978, Nkosi and composer Stanley Glasser wrote a collection of six Zulu-style songs called Lalela Zulu for The King's Singers, a group of six white British, male a cappella singers.

Quotations

editOn the situation in South Africa during apartheid

- "Africans have learned that if they are remaining sane at all it is pointless to try to live within the law. In a country where the Government has legislated against sex, drinks, employment, free movement and many other things, which are taken for granted in the Western world, it would take a monumental kind of patience to keep up with the demands of the law. A man's sanity may even be in question by the time he reaches the ripe age of twenty-five." (Nkosi: Home and Exile, 22)

On black writers and their literature

- "Black South Africans did not produce on elite which was alienated form the black masses or even from the conditions of everyday life under which our people laboured. In South Africa we were saved from the emergence of Black Bourgeoisie by the leveling effect of apartheid." (Nkosi: Home and Exile, 32)

On his exile

- "A writer needs his roots; he needs his people perhaps more than they need him in order that they should corroborate the vision he has of them, or at least, to dispute the statements he may make about their lives." (Nkosi: Home and Exile, 93)

On the writers and commitment

- "…whether we consider ourselves revolutionaries or not, are playing a marginal role. We may be good for propaganda; we may raise some money and build up contacts for the people of South Africa-but there is no such thing as a revolution fought in exile, without a base among the oppressed masses of the country for which the change is desired." (Nkosi: On South Africa, 286–292)

- "Ambushed by history, deprived of the moral and material support of the socialist camp by the fall of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, a negotiated peace, between a lame government and weary liberation movements was probably the next best thing.… The negotiated peace enacted what Doris Somer, writing about the South Africa, described as a premature end of a history." (The Republic of Letters: Mandela’s Republic)

Critical appraisal and research

editThe first comprehensive and critical review on Nkosi appeared in 2006, edited by Professor Lindy Steibel and Professor Liz Gunner, entitled Still Beating the Drum: Critical Perspectives on Lewis Nkosi, published by Wits University Press.[17][18]

Nkosi's works are gaining recognition and being prescribed as university and college textbooks. Some of his works of criticism and essays have been accepted as standard reference texts in the area of African literary criticism and literature. Research on Nkosi's work has also gained momentum across the Third World countries. He is a featured writer in the KZN Literary Tourism project.[19][20]

Writing Home: Lewis Nkosi on South African writing, a collection edited by Lindy Stiebel and Michael Chapman, was published in 2016, drawing on his collections Home and Exile (1965), The Transplanted Heart (1975) and Tasks and Masks (1981), and other writings from journals and magazines.[21] In 2021, other texts and two plays by Nkosi were included in the book Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist | Flying Home! Texts, Perspectives, Homage, edited by Astrid Starck-Adler and Dag Henrichsen.[22]

Bibliography

edit- Collections of essays

- Home and Exile, Longman, 1965

- Home and Exile and other selections, Longman, 1983, ISBN 0-582-64406-2

- The Transplanted Heart: Essays on South Africa, 1975

- Tasks and Masks: Themes and Styles of African Literature, Longman, 1981, ISBN 0-582-64145-4

- Plays

- The Rhythm of Violence (1964)

- The Chameleon and the Lizard

- The Black Psychiatrist (2001)

- Novels

- Mating Birds, Constable, 1986, ISBN 0-09-467240-7 (Winner of the Macmillan Pen prize)

- Underground People, Kwela Books, 2002, ISBN 0-7957-0150-0, originally published in Dutch in 1994

- Mandela's Ego, Struik, 2006, ISBN 1-4152-0007-6

- Short stories

- "The Hold-Up", Lusaka, Zambia: Wordsmith

- Films

- Nkosi shared the writing credits with Lionel Rogosin on Come Back, Africa (1959),[1] a film shot mainly in Sophiatown.

Awards

edit- 1961: Nieman Fellowship, Harvard University

- 1965: Dakar Festival Prize

- 1977: C. Day-Lewis Fellowship

- 1987: Macmillan Silver Pen Award

- 2009: Presidential National Order of Ikhamanga: Silver (OIS)[23]

Posthumous honour

editIn February 2011, wordsetc.co.za published a commemorative volume entitled The Beautiful Mind of Lewis Nkosi.

On 13 June 2011, Nadine Gordimer participated in a colloquium to commemorate the life and works of Lewis Nkosi.[24]

On 12 April 2012, the Durban University of Technology (DUT) conferred on Nkosi a posthumous honorary Doctor of Technology degree in Arts and Design in recognition of his significant contributions as a prolific and profound South African writer and essayist.[25] The award was accepted by his widow, Professor Astrid Starck-Adler, at the graduation ceremony at the DUT Midlands Campus. She was also the guest speaker during the ceremony.[26]

References

edit- ^ a b "Lewis Nkosi", South African History Online.

- ^ "Lewis Nkosi", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Horn, Peter (1994), "A radical rethinking of the art of poetry in an apartheid society", in Writing My Reading: Essays on Literary Politics in South Africa, Rodopi, p. 49, note 2.

- ^ "Lewis Nkosi, the first black South African fellow, dies at 73", Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, 9 September 2010.

- ^ a b Herbstein, Denis (22 September 2010). "Lewis Nkosi obituary". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b Shostak, E. "Nkosi, Lewis 1936–". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Three Swings on a Pendulum", BBC iPlayer.

- ^ Makatile, Don (8 September 2010). "Widow bereft as Nkosi's esteemed works add up to nothing". Sowetan. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Masilela, Ntongela (7–8 September 2010). "Lewis Nkosi (1936–2010): An Appreciation". New African Movement. Claremont (Los Angeles), California: Pitzer College.

- ^ Makube, Tiisetso (12 September 2010). "Obituary: Lewis Nkosi: Author, critic". Times Live.

- ^ SAPA (7 September 2010). "Lewis Nkosi dies". Times Live.

- ^ Brink, André (May 1992). "An Ornithology of Sexual Politics: Lewis Nkosi's 'Mating Birds'". English in Africa. 19 (1). Rhodes University: 1. JSTOR 40238684. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Rosenthal, Jane (1 November 202). "Notes from underground". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Stiebel, Lindy (October 2012). "Correspondence: Linking the Private to the Public in Lewis Nkosi's Novels". English in Africa. 39 (3). Rhodes University: 15–30. doi:10.4314/eia.v39i3.1. JSTOR 24389442. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ Gunner, Liz, "Contaminations: BBC Radio and the Black Artist — Lewis Nkosi's "The Trial" and "We Can't All be Martin Luther King", in Lindy Stiebel and Liz Gunner (eds), Still Beating the Drum: Critical Perspectives on Lewis Nkosi, Rodopi, 2005, pp. 51–66.

- ^ Lefanu, Sara and Stephen Hayward (1990), Colours of a New Day (London: Lawrence and Wishart, pp. xiii, 287.

- ^ Lindy Steibel and Liz Gunner (eds), "Still Beating the Drum: Critical Perspectives on Lewis Nkosi" (Cross/Cultures 81)[permanent dead link], KwaZuluNatal University Press, 2006. ISBN 1-86814-435-6.

- ^ Mkhize, Jabulani (January 2008). "Shades of Nkosi: Still Beating the Drum" (PDF). Alternation. 15 (2): 416–426. ISSN 1023-1757. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Southafrica.net. "KwaZulu-Natal Literary Tourism Route". southafrica.net. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "Lewis Nkosi". KZN Literary Tourism. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Stiebel, Lindy; Michael Chapman, eds. (2016). Writing home : Lewis Nkosi on South African writing. University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. ISBN 9781869143091.

- ^ Slasha, Unathi (12 November 2021). "Lewis Nkosi: The physical bearer of the offending word". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Lewis Nkosi (1936 – ) | The Order of Ikhamanga in Silver". The Presidency, Republic of South Africa.

- ^ Minors, Deborah (19 July 2011). "Gordimer, Mtshali, Khumalo remember Lewis Nkosi". Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

- ^ Khan, Alan, "DUT posthumous honorary Doctorate for Professor Lewis Nkosi", Durban University of Technology, 28 February 2012. Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jansen, Leanne (27 February 2012). "Honours for top South Africans". IOL News.

Further reading

edit- Bernth Lindfors (ed.), Conversations With Chinua Achebe, University Press of Mississippi (October 1997)

- Geoffrey V. Davis (ed.), Southern African Writing: Voyages and Explorations, Rodopi (January 1994)

- Lindy Stiebel and Liz Gunner (eds), Still Beating the Drum: Critical Perspectives on Lewis Nkosi, KwaZuluNatal University Press, 2006. ISBN 1-86814-435-6

- Gall, Emily. "Lewis Nkosi: A Fragile Soul’s Quest for Home", English in Africa 39, no. 3 (2012): 65–80.

External links

edit- Sandile Ngidi, "Lewis Nkosi Selected Milestones: Writing and Honours", Mail & Guardian, 12 November 2021.

- Tribute to Lewis Nkosi by the Minister of Arts and Culture, Ms Lulama Xingwana MP, South African Government Information, 8 September 2010.

- "RIP Lewis Nkosi, 1936 – 2010", Sunday Times Books Live, 6 September 2010.

- Vuyo Seripe, "Writer's Block", Mahala, 28 September 2010.

- "Lewis Nkosi, writer and academic", The Witness, 16 September 2010; reprinted in Pambazuka News.

- "Lewis Nkosi (1936–2010): An Appreciation", Post-Colonial Networks.

- Litzi Lombardozzi, "The Journey Beyond Embo: the construction of place and identity in the writings of Lewis Nkosi", University of Kwa-Zulu Natal. "Journeying beyond Embo: the construction of exile, place and identity in the writings of Lewis Nkosi", dissertation, January 2007.

- A documentary on Lewis Nkosi

- Ryan Wells, "Hands Off, Westerner", Cinespect, 24 January 2012.

- Zodidi Mhlana, "Follow the literary trails of great writers", The New Age Online, 23 February 2012.

- Janice Harris, "On Tradition, Madness, and South Africa: An Interview with Lewis Nkosi". Weber State University, Spring/Summer 1994, Volume 11.2.