The testicular vein (or spermatic vein), the male gonadal vein, carries deoxygenated blood from its corresponding testis to the inferior vena cava or one of its tributaries. It is the male equivalent of the ovarian vein, and is the venous counterpart of the testicular artery.

| Testicular vein | |

|---|---|

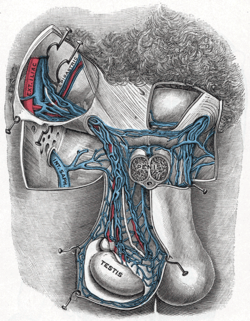

Spermatic veins. | |

| Details | |

| Source | Pampiniform plexus |

| Drains to | Inferior vena cava, left renal vein |

| Artery | Testicular artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vena testicularis, vena spermatica |

| TA98 | A12.3.09.014M A12.3.09.012M |

| TA2 | 5015, 5018 |

| FMA | 14344 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Structure

editIt is a paired vein, with one supplying each testis:

- the right testicular vein generally joins the inferior vena cava;

- the left testicular vein, unlike the right one, joins the left renal vein instead of the inferior vena cava.

The veins emerge from the back of the testis, and receive tributaries from the epididymis.[1] They unite and form a convoluted plexus, called the pampiniform plexus, which constitutes the greater mass of the spermatic cord; the vessels composing this plexus are very numerous, and ascend along the cord, in front of the ductus deferens.

Below the subcutaneous inguinal ring, they unite to form three or four veins, which pass along the inguinal canal, and, entering the abdomen through the abdominal inguinal ring, coalesce to form two veins, which ascend on the Psoas major, behind the peritoneum, lying one on either side of the internal spermatic artery.

These unite to form a single vein, which opens, on the right side, into the inferior vena cava (at an acute angle), on the left side into the left renal vein (at a right angle).

The left spermatic vein passes behind the iliac colon and is thus exposed to pressure from the contents of that part of the bowel.

Variation

editThe testicular veins usually have valves.[1] However, in post-mortem examinations it was found that up to 40% of left testicular veins lack valves, and up to 23% of right testicular veins lack valves.[1]

Clinical significance

editVaricocele

editValveless testicular veins are a major contributing factor to varicocele.[1] Since the left testicular vein goes all the way up to the left renal vein before it empties, this results in a higher tendency for the left testicle to develop varicocele because of the gravity working on the column of blood in this vein, compared to the right internal spermatic vein. One reason for this susceptibility is that the left internal testicular vein often drains into the left renal vein without a right-angle entry like it is with the right testicular vein, which can create increased pressure and possibly disrupt the normal valve function, leading to poor venous return and eventually varicocele development.[2]

The testicular vein may be ligated in part (a branch) or completely to treat varicocele.[3] This is typically very safe.[3] There is debate about whether the testicular artery should also be ligated simultaneously.[3] Affected testicular veins can also be removed completely to further reduce recurrence rates.[citation needed]

Compression

editThe left renal vein passes between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery en route to the inferior vena cava, and is often compressed by an enlarged superior mesenteric artery—this is called the "Nutcracker effect".[4]

Additional images

edit-

Diagram showing completion of development of the parietal veins.

-

The veins of the right half of the male pelvis.

-

The relations of the viscera and large vessels of the abdomen.

-

Transverse section through the left side of the scrotum and the left testis.

-

The spermatic cord in the inguinal canal.

-

Testicular vein

References

editThis article incorporates text in the public domain from page 678 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c d Hutson, John M. (2012-01-01), Coran, Arnold G. (ed.), "Chapter 77 - Undescended Testis, Torsion, and Varicocele", Pediatric Surgery (Seventh Edition), Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 1003–1019, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07255-7.00077-5, ISBN 978-0-323-07255-7, retrieved 2021-02-04

- ^ Hutson, John M. (2012), "Undescended Testis, Torsion, and Varicocele", Pediatric Surgery, Elsevier, pp. 1003–1019, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07255-7.00077-5, ISBN 978-0-323-07255-7, retrieved 2023-10-04

- ^ a b c Zelkovic, Paul; Kogan, Stanley J. (2010-01-01), Gearhart, John P.; Rink, Richard C.; Mouriquand, Pierre D. E. (eds.), "The Pediatric Varicocele", Pediatric Urology (Second Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 585–594, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-3204-5.00045-1, ISBN 978-1-4160-3204-5, retrieved 2021-02-04

- ^ Ahmed K, Sampath R, Khan MS (April 2006). "Current trends in the diagnosis and management of renal nutcracker syndrome: a review". European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 31 (4). European Society for Vascular Surgery: 410–416. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.05.045. PMID 16431142.

External links

edit- Anatomy photo:40:13-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Posterior Abdominal Wall: Tributaries to the Inferior Vena Cava"