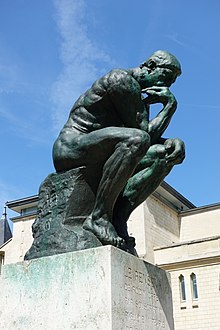

The Thinker (French: Le Penseur), by Auguste Rodin, is a bronze sculpture situated atop a stone pedestal depicting a nude male figure of heroic size sitting on a rock. He is seen leaning over, his right elbow placed on his left thigh, holding the weight of his chin on the back of his right hand. The pose is one of deep thought and contemplation, and the statue is often used as an image to represent philosophy.

| The Thinker | |

|---|---|

Le Penseur (1904) in the Musée Rodin in Paris | |

| Artist | Auguste Rodin |

| Year | 1904 |

| Medium | Bronze |

Rodin conceived the figure as part of his work The Gates of Hell commissioned in 1880, but the first of the familiar monumental bronze castings was made in 1904, and is now exhibited at the Musée Rodin, in Paris.

There are 27 other known full-sized castings, in which the figure is approximately 185 cm (73 inches) high, though not all were made during Rodin's lifetime and under his supervision. There are various other versions, several in plaster, and studies and posthumous castings exist in a range of sizes.

Origin

editThe Thinker was initially named The Poet (French: Le Poète), and was part of a large commission begun in 1880 for a doorway surround called The Gates of Hell. Rodin based this on the early 14th century poem The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri, and most of the figures in the work represented the main characters in the poem with The Thinker at the center of the composition over the doorway and somewhat larger than most of the other figures. Some critics believe that it was originally intended to depict Dante at the gates of Hell, pondering his great poem.

Other critics reject that theory, pointing out that the figure is naked while Dante is fully clothed throughout his poem, and that the sculpture's physique does not correspond to Dante's effete figure.[1] The sculpture is nude, as Rodin wanted a heroic figure in the tradition of Michelangelo, to represent intellect as well as poetry.[2] Other critics came to see the sculpture as a self-portrait.[1][3] This detail from the Gates of Hell was first named The Thinker by foundry workers, who noted its similarity to Michelangelo's statue of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, called Il Pensieroso (The Thinker).[1]

The model for this sculpture, as for other works by Rodin, was the muscular French prizefighter and wrestler Jean Baud, who mostly appeared in the red-light district. Jean Baud was also featured on the 1911 Swiss 50 franc note by Hodler.

The original is in the Musée Rodin in Paris. The sculpture has a height of 72 cm, was made of bronze and had been finely patinated and polished. The work depicts a nude male figure of heroic size who is tense, muscular and internalized, contemplating the actions and fate of the people while sitting on a rock. He is seen leaning over, his right elbow placed on his left thigh, holding the weight of his chin on the back of his right hand. The pose is one of deep thought and contemplation, and the statue is often used as an image to represent philosophy. This and many other works by Rodin were groundbreaking for modernism and heralded a new age of three-dimensional artistic creation.

The work was enlarged in 1902 to a height of 181 cm. The monumental version became the artist's first work in public space. The figure was designed to be seen from below and is normally displayed on a fairly high plinth, although the heights vary considerably chosen by the various owners.

Casts

editThe Thinker has been cast in multiple versions and is found around the world, but the history of the progression from models to castings is still not entirely clear. About 28 monumental-sized bronze casts are in museums and public places. In addition, there are sculptures of different study-sized scales and plaster versions (often painted bronze) in both monumental and study sizes. Some newer castings have been produced posthumously and are not considered part of the original production.

Rodin made the first small plaster version around 1881. The first bronze version was executed in 1884 and is held at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. The first full-scale model was presented at the Salon des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1904. A public subscription financed a bronze casting, which became the property of the City of Paris, and was put in front of the Panthéon.[4] In 1922, the original bronze was moved to the Musée Rodin.

Art market

editIn June 2022 a cast was put up for sale at Christie's in Paris with an estimate of up to €14m. The cast was made in about 1928 at the Rudier Foundry, founded by Alexis Rudier (1845-1897) who worked with Antoine Bourdelle and Aristide Maillol.[5]

Reception

editMax Linde had a copy of the monumental version cast in 1904 and placed it in the garden of his villa, Lindesche Villa. There Edvard Munch painted his painting Rodin's Thinker in the Garden of Dr. Linde, which is now in the Behnhaus. The cast later went to the Detroit Institute of Arts.[6]

In his film The Great Dictator, Charlie Chaplin shows the Venus de Milo and Rodin's Thinker with the modification that the left arms are stretched out in the Hynkel salute.[7] With this allusion to the Nazi salute, Chaplin addresses the integration of art into Nazi propaganda.[8] In the film Night at the Museum 2, the protagonists encounter a statue of the Thinker that has been brought to life. When asked a question, he stutters: "I think...I think...I think." Later in the film, he flirts with a statue of Aphrodite.[9] In Death at a Funeral, the statue is quoted as Alan Tudyk sitting naked on a rooftop in a "thinking pose."[10] In Midnight in Paris, the then French first lady Carla Bruni made a cameo appearance as a tour guide, explaining the sculpture of the Thinker to a group of American visitors in the garden of the Musée Rodin.

In singer Ariana Grande's "God Is a Woman" music video, she sits in the Thinker pose while being attacked by small angry men. They throw into them words taken from the book they are on. However, these bounce off the singer when they reach her.

As part of the Stadt.Wand.Kunst project launched in Mannheim for the painting of houses in the city with large-scale wall paintings (so-called murals) by national and international artists from the street art scene, Rodin's Thinker was taken up and the mural The Modern Thinker implemented.

Similar sculptures

editRepetitive portrayals of individuals, both male and female, have been depicted in physical form while in the process of contemplation or grieving.

The "Karditsa Thinker" is a Neolithic clay figurine found in the area of Karditsa in Thessaly, Greece. This unique artifact, dated around 3900 BCE, during the Final Neolithic period (4500-3300 BCE), is a large solid clay figurine of a seated man. Despite some clumsiness in detail, it conveys the impression of a robust man looking upwards with a manly bearing. The figurine exhibits features of fully developed sculpture and is considered the largest Neolithic artifact found in Greece. The pronounced ithyphallic element, though mostly broken, along with its size, suggests a possible cultic character, possibly representing an agrarian deity associated with the fertility of the land.[11][12]

The Thinker from Yehud, also known as the Thinker of Palestine,[13] is an archaeological figurine discovered during salvage excavations in the Israeli city of Yehud. The figurine, which sits atop a ceramic jug in a posture resembling "The Thinker", dates back to the Middle Bronze Age II Palestine (c. 1800–1600 BCE). It was found in a tomb accompanied by various items, including daggers, spearheads, an axe head, a knife, two male sheep, and a donkey, all likely buried as offerings. After its discovery, the broken jug had to be stabilised and restored before being displayed in the Canaanite Galleries of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.[14]

The "Thinker of Cernavodă", Romania, a terracotta sculpture, and its female counterpart, "The Sitting Woman", are works of art from the Chalcolithic era. The Hamangia culture produced these remarkable sculptures, with The Thinker believed to be the earliest prehistoric sculpture that conveys human self-reflection instead of the more common artistic themes of hunting or fertility.[15][16] The discovery of the Spong Man, which is the earliest known Anglo-Saxon sculpture of a person, was found in Europe's other end, five millennia.[17] The sculpture takes the form of a seated figure on a pottery lid of a cremation urn, resembling a humanoid figure.[18]

A thousand years later, Michelangelo created the tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, which is located in the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence, Italy. The tomb is a sculptural masterpiece and was commissioned by Pope Clement VII to honor the memory of the Duke of Urbino, a member of the powerful Medici family of Florence. The tomb is considered one of Michelangelo's finest works in sculpture and was created in the Mannerist style of the Late Renaissance period.[19] The tomb features a large rectangular base, which is adorned with intricate reliefs and two sculptures, Dusk and Dawn, that represent the cycle of life.[20] The central figure on the tomb is a sculpture of the Duke, who is portrayed as a thinker with his face in shadow and his elbow resting on a money box with a similarly muscular, contemplative figure with his hand on his chin, though the figure is seated rather than standing like Rodin's "The Thinker". The tomb also includes two reclining figures on the sarcophagus that are believed to represent Day and Night.[21]

-

Karditsa Thinker (4500-3300 BCE)

-

The Spong Man lid at Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Elsen, Albert L., Rodin's Gates of Hell, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis Minnesota, 1960 p. 96.

- ^ Gibson, E. (2023). "Rodin & Michelangelo: A Speculation". The New Criterion. 42 (4): 16–21 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "The Thinker by Auguste Rodin". www.thehistoryofart.org.

- ^ Brocvielle, Vincent, Le Petit Larousse de l'Histore de l'Art (in French), (2010), pg. 240.

- ^ "Rodin's the Thinker to sell for up to €14m". 7 April 2022.

- ^ "Alexis Rudier casts". 2011-07-19. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Clausius, Claudia (1989). The gentleman is a tramp : Charlie Chaplin's comedy. New York: P. Lang. p. 127. ISBN 0-8204-0459-4. OCLC 17776035.

- ^ Insdorf, Annette (2003). Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01630-8.

- ^ "Quotes from "Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian"". IMDb. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ Edelstein, David (10 August 2007). "Stardust - Death at a Funeral - The 11th Hour - Manda Bala -- New York Magazine Movie Review - Nymag". New York Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ "The Thinker". ancient-greece.org. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ "Photo-National Archaeological Museum - Neollithic Thinker from Karditsa". www.athensguide.com. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ Ζηνων (2017-09-11). "Αυτόχθονες Έλληνες: ΟΙ ΤΡΕΙΣ ΣΤΟΧΑΣΤΕΣ, ΤΗΣ ΚΑΡΔΙΤΣΑΣ, ΤΗΣ ΠΑΛΑΙΣΤΙΝΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΟΥ ΡΟΝΤΕΝ". Αυτόχθονες Έλληνες. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ "4000-year-old Version of Rodin's 'Thinker' Found in Israel". Haaretz. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ ""The Thinker" and "Sitting Woman", the symbols of the Neolithic culture of Hamangia. – Romania Color". Archived from the original on 2023-04-03. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ^ Coca, Madalina Cristiana (2022), "Cernavoda—CANDU nuclear power plants in Romania", Pressurized Heavy Water Reactors, Elsevier, pp. 429–441, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-822054-2.00007-6, ISBN 9780128220542, S2CID 241284395, retrieved 2023-04-03

- ^ "Spong Man". British Library collections. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "Object: Funerary urn (collection)". norfolkmuseumscollections.org. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ "Tomb of Lorenzo de Medici, 1524 - 1531 - Michelangelo - WikiArt.org". www.wikiart.org. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ^ "Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici by MICHELANGELO Buonarroti". www.wga.hu. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ^ "Grande Arte • A Digital Library for Art Lovers • Michelangelo • THE TOMB OF GIULIANO DE' MEDICI". grandearte.net. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

External links

edit- The "Penseur", a poem by Philadelphia poet Florence Earle Coates at Wikisource

- Artwork listing at the Musée Rodin website

- The Thinker Inspiration, Analysis and Critical Reception

- The Thinker project Archived 2012-09-06 at archive.today, Munich. Discussion of the history of the many casts of this artwork.

- The Thinker, Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Object Number 1988.106, bronze cast No. 10, edition of 12.

- Auguste Rodin and The Thinker Archived 2018-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, the story behind his most iconic sculpture of all time at biography.com.

- Rodin: The B. Gerald Cantor Collection, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which contains material on The Thinker