La Jolla (/lə ˈhɔɪə/ lə HOY-ə, Latin American Spanish: [la ˈxoʝa]) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood in San Diego, California, occupying 7 miles (11 km) of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781.[2] The climate is mild, with an average daily temperature of 70.5 °F (21.4 °C).[3][4]

La Jolla, San Diego | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: "The Jewel" | |

| Coordinates: 32°50′24″N 117°16′37″W / 32.84000°N 117.27694°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Diego |

| City | San Diego |

| Founded: | 1850[1] |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

• Total | 46,781 |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (UTC--08:00) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (UTC--07:00) |

| ZIP Code | 92037-92039, 92092, 92093 |

| Area code(s) | 858, 619 |

| Website | LaJolla.com |

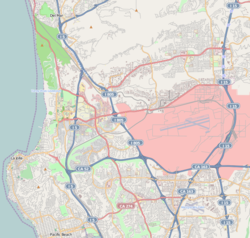

La Jolla is surrounded on three sides by ocean bluffs and beaches[5] and is located 12 miles (19 km) north of downtown San Diego and 45 miles (72 km) south of the Orange County line.[6][7] The neighborhood's border starts at Pacific Beach to the south and extends along the Pacific Ocean shoreline north to include Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve ending at Del Mar.

La Jolla is home to many educational institutions and a variety of businesses in the areas of lodging, dining, shopping, software, finance, real estate, bioengineering, medical practice and scientific research.[5][8][9] The University of California, San Diego is located in La Jolla, as is Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Scripps Research, and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

History

editOrigin of the name

editLocal Native Americans, the Kumeyaay, called this location mat kulaaxuuy (IPA [mat kəlaːxuːj]), lit. 'land of holes' (mat = 'land').[10] The topographic feature that gave rise to the name "holes" is uncertain; it probably refers to sea-level caves located on the north-facing bluffs, which are visible from La Jolla Shores. It is suggested[citation needed] that the Kumeyaay name for the area was transcribed by the Spanish settlers as La Jolla. Another suggestion for the origin of the name is that it is an alternative spelling of the Spanish phrase la joya, which means 'the jewel'. Despite being disputed by scholars, this derivation of the name has been widely cited in popular culture.[11] This supposed origin gave rise to the nickname "The Jewel".[12] The name may also come from the Spanish La Hoya, meaning a geographic hollow. Different spelling conventions over the years would permit this to be written as La Jolla.[13]

Early history

editDuring the Mexican period of San Diego's history, La Jolla was mapped as pueblo land and contained about 60 lots. When California became a state in 1850,[14] the La Jolla area was incorporated as part of the chartered City of San Diego.[1] In 1870, Charles Dean acquired several of the pueblo lots and subdivided them into an area that became known as La Jolla Park. Dean was unable to develop the land and left San Diego in 1881. A real estate boom in the 1880s led speculators Frank T. Botsford and George W. Heald to further develop the sparsely settled area.

In the 1890s, the San Diego, Pacific Beach, and La Jolla Railway was built, connecting La Jolla to the rest of San Diego. La Jolla became known as a resort area. To attract visitors to the beach, the railway built facilities such as a bath house and a dance pavilion. Visitors were housed in small cottages and bungalows above La Jolla Cove, as well as a temporary tent city erected every summer. Two of the cottages that were built in 1894, the "Red Roost" and the "Red Rest", also known as the "Neptune and Cove Tea Room", still exist and are the oldest buildings in La Jolla that are still on their original site. The two cottages have been vacant since the 1980s, boarded up and covered in tarpaulins while their fate was debated. In November 2020 the Red Rest was largely destroyed by fire.[15]

The La Jolla Park Hotel opened in 1893. The Hotel Cabrillo was built in 1908 by "Squire" James A. Wilson and was later incorporated into the La Valencia Hotel.[16]

By 1900, La Jolla comprised 100 buildings and 350 residents. The first reading room (library) was built in 1898.[16] A volunteer fire brigade was organized in 1907; the city of San Diego established a regular fire house in 1914. Livery stable owner Nathan Rannells served successively as La Jolla's volunteer fire captain, first police officer (the only San Diego police officer north of Mission Valley), and first postmaster.[17]

La Jolla Elementary School began educating local children in 1896.[18] The Bishop's School opened in 1909. La Jolla High School was established in 1922. Between 1951 and 1963, other elementary schools (Bird Rock, Decatur, Scripps, and Torrey Pines) were established in the area to ease overcrowding.[18] The La Jolla Beach and Yacht Club (later the La Jolla Beach and Tennis Club) was built in 1927.[16]

Ellen Browning Scripps

editIn 1896 journalist and publisher Ellen Browning Scripps settled in La Jolla, where she lived for the last 35 years of her life. She was wealthy in her own right from her investments and writing, and she inherited a large sum from her brother George H. Scripps in 1900. She devoted herself to philanthropic endeavors, particularly those benefiting her adopted home of La Jolla. She commissioned many of La Jolla's most notable buildings, usually designed by Irving Gill or his nephew and partner Louis John Gill. Many of these buildings are now on the National Register of Historic Places or are listed as historic by the city of San Diego; these include the La Jolla Woman's Club (1914), the La Jolla Recreational Center (1915), the earliest buildings of The Bishop's School, and the Old Scripps Building at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, as well as her own residence, built in 1915 and now housing the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Her donations also launched Scripps Memorial Hospital in 1924 (originally located on Prospect Street in La Jolla until it moved to its present site in 1964), the Scripps Metabolic Clinic (now Scripps Research), and the Children's Pool. Ellen Browning Scripps also founded Scripps College, a women's college, in 1926.[19] Scripps College is located in Claremont in Los Angeles County (not to be confused with Clairemont, a neighborhood of San Diego).

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

editScripps Institution of Oceanography, one of the nation's oldest oceanographic institutes, was founded in 1903 by William Emerson Ritter, chair of the zoology department at the University of California, Berkeley, with financial support from Scripps and her brother E. W. Scripps. At first the institution operated out of a boathouse in Coronado. In 1905, they purchased a 170-acre (69 ha) site in La Jolla, where the Institution still stands today. The first laboratory buildings there opened in 1907. The institution became part of the University of California in 1912. Ultimately, it became the nucleus for the establishment of the University of California, San Diego.

Camp Matthews

editFrom 1917 through 1964, the United States Marine Corps maintained a military base in La Jolla. The base was used for marksmanship training and was known as Camp Calvin B. Matthews. During and after World War II, the population of La Jolla grew, causing residential development to draw close to the base, so that it became less and less suitable as a firing range because of risk to the adjacent civilian population.[20] Meanwhile, the site was being eyed as a location for a proposed new campus of the University of California. In 1962, Camp Matthews was declared surplus by the Marine Corps. The base formally closed in 1964, and that same year, the first class of undergraduates enrolled in the University of California San Diego.

University of California, San Diego

editLocal civic leaders had long toyed with the idea of a San Diego campus of the University of California, and the quest became more definite following World War II. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, under its director Roger Revelle, had become an important defense contractor, and local aerospace companies like Convair were pressing for local training for their scientists and engineers. The state legislature proposed the idea in 1955, and the Regents of the university formally approved it in 1960.[21] During the planning stage of the university's establishment, it was briefly known as the "University of California, La Jolla", but the name was changed to "University of California, San Diego" before its founding in 1960.[22] The founding chancellor was Herbert York, named in 1961, and the second chancellor was John Semple Galbraith, named in 1964. The university was designed to have a "college" system; there are now eight colleges. The first college was established in 1965 and was named Revelle College after Roger Revelle, who is regarded as the "father" of the university.[22] A medical school was established in 1968. The landmark Geisel Library with its Brutalist architecture opened in 1970. The university is the second largest employer in the city and has the 7th largest research expenditure in the country.[23]

Antisemitism

editThe Camp Matthews site for the university was selected with some hesitation; one of the concerns was "whether La Jollans in particular would lay aside old prejudices in order to welcome a culturally, ethnically, and religiously diverse professoriate into their midst".[21] La Jolla had a history of restrictive housing policies, often specified in deeds and ownership documents. In La Jolla Shores and La Jolla Hermosa, only people with pure European ancestry could own property; this excluded Jews, who were not considered white. Such "restrictive covenants" were once fairly common throughout the United States; the 1948 Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer ruled them to be unenforceable, and Congress outlawed them twenty years later via the Fair Housing Act (Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968).[24] However, realtors and property owners in La Jolla continued to use more subtle ways of preventing or discouraging Jews from owning property there.[25] Revelle stated the issue bluntly: "You can't have a university without having Jewish professors. The Real Estate Broker's Association and their supporters in La Jolla had to make up their minds whether they wanted a university or an anti-Semitic covenant. You couldn't have both."[26] The issue was overcome; La Jolla now boasts a thriving Jewish population,[27] and there are four synagogues in La Jolla.[28]

Mount Soledad cross

editMount Soledad is an 822-foot-tall (251 m) hill on the eastern edge of La Jolla and one of the highest points in San Diego. A large Christian cross was placed at the top in 1913 as a prominent landmark. It has been replaced twice, most recently in 1954 with a 29-foot-tall (8.8 m) cross (43 feet (13 m) tall including the base). Originally known as the "Mount Soledad Easter Cross", its presence on publicly owned land was challenged in the 1980s as a violation of the separation of church and state. Since then the cross has had a war memorial built around it and was renamed "Mount Soledad Veterans War Memorial".[29]

The issue has been in almost continual litigation ever since, with the city attempting to sell or give away the land under the cross. By an act of Congress, the federal government took possession of it under eminent domain in 2006. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit declared the cross unconstitutional in 2011, and the Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear an appeal.[30] In December 2013, U.S. District Judge Larry Burns ordered that the cross be removed within 90 days, but stayed the order pending a forthcoming appeal by the government.[31][32]

On July 20, 2015, a group called the Mt. Soledad Memorial Association reported that it had bought the land under the cross from the Department of Defense for $1.4 million.[33] On September 7, 2016, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued a one-page ruling, ordering dismissal of the case and an end to all current appeals, stating that the case was now moot because the cross was no longer on government land. Both sides agreed that this decision puts a final end to the case.[34]

Arts

editLa Jolla became an art colony in 1894 when Anna Held (also known as Anna Held Heinrich) established the Green Dragon Colony. This was a cluster of twelve rustic cottages that included The Green Dragon, Wahnfried, and The Ark, a boat-shaped structure with port holes and swinging bunks.[35]

The La Jolla Playhouse was founded in 1947 by Gregory Peck, Dorothy McGuire, and Mel Ferrer.[36] It became inactive in 1959, but was revived in 1983 on the University of California campus under the leadership of Des McAnuff. It now incorporates three theaters: the Mandell Weiss Theatre (1983), the Mandell Weiss Forum (1991) and the Potiker Theater (2005).

The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego was founded in 1941 in La Jolla, in the former home of Ellen Browning Scripps (designed by Irving J. Gill). The museum has undergone several renovations and expansions, and is working on plans to triple its size.[37][38]

The La Jolla Music Society was founded in 1941 as the Musical Arts Society of La Jolla by Nikolai Sokoloff, former conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra. It presented the premieres of commissioned works in the auditorium of La Jolla High School before presenting their concerts in the Sherwood Auditorium of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Since April 2019, the Conrad Prebys Performing Arts Center is the permanent home of La Jolla Music Society and hosts world-class performances presented by LJMS as well as other San Diego arts presenters. Additionally, The Conrad will see a wide range of conferences, corporate meetings, and private events.

Geography

editDemarcation

editThe neighborhoods's border starts at Pacific Beach to the south and extends along the Pacific Ocean shoreline north to include Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve ending at Del Mar. La Jolla encompasses the neighborhoods[39] of Bird Rock, Windansea Beach, the commercial center known as the Village of La Jolla, Muirlands, La Jolla Shores, La Jolla Farms, Torrey Pines, and Mount Soledad to name a few.

The City of San Diego defines the neighboorhood's eastern boundary as Gilman Drive and the Interstate 5 freeway[40] and the northern boundary as UCSD.[41]

The United States Postal Service defines a somewhat larger area, assigning the neighborhood the 92037 ZIP Code, recognizing it as a historically and geographically distinct area. This unique ZIP code allows addresses to read La Jolla, CA, and is the only neighborhood within the City of San Diego so recognized. Additionally, it is in the 919xx/920xx sequence used for suburban and rural ZIP Codes in San Diego County, rather than the 921xx sequence used for the remainder of the City of San Diego. These conditions sometimes lead to the erroneous impression that La Jolla is a separate city, rather than a part of San Diego. The 92037 ZIP code extends the northeasterly boundary to Genesee Avenue and the northerly boundary to Del Mar, California. The UCSD campus, also part of La Jolla, has ZIP Codes 92092 and 92093.

Despite the city and postal service definitions, La Jolla does not have universally accepted boundaries. In the 1980s, the trustees of Scripps Hospital voted to move the campus from downtown La Jolla to University City, east of Interstate 5 and not within the traditional boundaries of La Jolla. The governing documents of the hospital required it to be located in La Jolla, however. A court ruled that "La Jolla" exists merely as a "state of mind" and thus allowed the relocation of the hospital.[42] Several businesses and housing developments east of Interstate 5 use "La Jolla" in their names despite being geographically located in the University City neighborhood of San Diego, which includes areas east of Interstate 5.

Wildlife

editLa Jolla's offshore waters are known to be home to an endless array of marine wildlife, including sea lions, harbor seals, whales—such as migratory gray, humpback and blue whales—harbor porpoises, dolphins (including, at times, hundreds of common dolphins, as well as rough-toothed, bottlenose, Pacific white-sided and Risso's dolphins, and orcas), green sea turtles, countless fish (such as garibaldi, sculpin and more), many migratory and resident sea and shorebirds,[43] and many different sharks, ranging from diminutive, clam-eating dogfish and leopard sharks to the formidable great white shark. Many of the marine animals live within and/or depend on the extensive offshore kelp forest, where scuba divers often venture to explore and encounter interesting species.[44] The kelp forests are also home to an extensive number of invertebrate species, from sea urchins, abalone, sea stars and limpets to king crab and giant octopus.

Oftentimes, tourists can see California sea lions and harbor seals hauled-out on the rocks, basking in the sun; however, as many local divers and swimmers can attest, pinnipeds are not always a good omen, as their presence usually lures bigger, predatory sharks—namely the great whites.[45][46] During the winter, these apex predators breed, hunting the plentiful seals around the kelp forest, and sometimes, coming even closer to shore.[47] Piers, caves, and buoys are areas that surfers avoid for these reasons, as sharks patrol these locations to ambush pinnipeds diving back into the water. However, with very few exceptions, the majority of shark encounters are uneventful and not aggressive, and, many times, great white sharks may come within mere feet of surfers or swimmers yet remain completely unnoticed; it is often only with drone footage that such close encounters are even observed.[48][49]

Geology

editLa Jolla is an area of mixed geology, including sandy beaches and rocky shorelines. The area is occasionally susceptible to flooding and ocean storms, as occurred in January and December 2010.[50]

Mount Soledad is covered with the narrow roads that follow its contours and hundreds of homes overlooking the ocean on its slopes. It is the home of the Mount Soledad Cross, built in 1954, later designated a Korean War Memorial, that became the center of a controversy over the display of religious symbols on government property.

The most compelling geographical highlight of La Jolla is its ocean front, with alternating rugged and sandy coastline that serves as habitat for many wild seal congregations. There are many beaches, accessible from the cliffs all throughout the coast of La Jolla. Locals and surfers will walk barefoot down to the beachfront, occasionally using ropes and planks to safely cross otherwise impassable, steep passageways down the cliff-face.[51] There are many notable tourist locations including Torrey Pines Gliderport, Blacks Beach, Sunset Cliffs, La Jolla Shores, La Jolla Cove, and more. Blacks Beach, commonly known for being one of the only nudist beaches in the area, is one of the most popular lesser known surfer spots throughout the year.[52] Torrey Pines Gliderport is another a staple of the La Jolla cliffs, offering views of gliders scattered throughout the air.[53] Sunset Cliffs is a location popular amongst locals and tourists alike, known for views of the sunset off to the horizon past the cliffs and caves below.[54] La Jolla Shores, not to be mistaken with La Jolla Cove, is located right next to Scripps Pier[55] and is close to many small shops, homes, and restaurants.[56] La Jolla Cove, the staple of La Jolla, is the most popular tourist destination[57] in La Jolla, featuring many snorkelers,[58] swimmers, and wildlife (most notably the La Jolla seals).[59][60] During some parts of the year, people will find the shallow ends of the beach filled with harmless leopard sharks, as they come closer to shore to breed.[61] All of the popular beaches and coastal access points, listed from north to south, include:

- Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve

- Black's Beach (a de facto nude beach)

- Scripps, near the Scripps Institution of Oceanography

- La Jolla Shores

- La Jolla Beach & Tennis Club

- La Jolla Cove

- Boomers Beach

- Shell Beach

- Children's Pool Beach

- Wipeout Beach

- Horseshoes

- Marine Street

- Windansea Beach

- Bird Rock

Climate

edit| Climate data for La Jolla, San Diego | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

103 (39) |

108 (42) |

104 (40) |

111 (44) |

107 (42) |

100 (38) |

88 (31) |

111 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

67 (19) |

68 (20) |

69 (21) |

70 (21) |

73 (23) |

77 (25) |

79 (26) |

78 (26) |

75 (24) |

71 (22) |

67 (19) |

72 (22) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 47 (8) |

49 (9) |

51 (11) |

54 (12) |

58 (14) |

61 (16) |

64 (18) |

66 (19) |

64 (18) |

59 (15) |

51 (11) |

47 (8) |

56 (13) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 29 (−2) |

36 (2) |

38 (3) |

40 (4) |

45 (7) |

50 (10) |

55 (13) |

57 (14) |

51 (11) |

43 (6) |

36 (2) |

34 (1) |

29 (−2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.73 (69) |

2.44 (62) |

2.66 (68) |

0.93 (24) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.09 (2.3) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.48 (12) |

1.23 (31) |

1.53 (39) |

12.77 (324) |

| Source: [62] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editAccording to United States Census Bureau figures, the ethnic/racial makeup of La Jolla is 82.5% White, 0.8% Black, 0.2% American Indian, 11.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 2.0% any other race, and 3.1% two or more races. Latinos, who may be of any race, form 7.2% of La Jolla's population. There is also a sizable Persian population in La Jolla.[63]

La Jolla had the highest home prices in the nation in 2008[64] and 2009,[65] according to a survey by Coldwell Banker. The survey compares the cost of a standardized four-bedroom home in communities across the country. The average price for such a home in La Jolla was reported as US$1.842 million in 2008 and US$2.125 million in 2009.

Neighborhoods

edit- La Jolla Farms — This northern La Jolla neighborhood is just west of UCSD. It includes Torrey Pines Gliderport, the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and a group of expensive homes on the cliffs above Black's Beach (one of which is the Audrey Geisel University House).

- La Jolla Shores — The residential area and Scripps Institution of Oceanography campus along La Jolla Shores Beach and east up the hillside. Also includes a small business district of shops and restaurants along Avenida de la Playa.

- La Jolla Heights — The homes on the hills overlooking La Jolla Shores. No businesses.

- Hidden Valley — Lower portion of Mount Soledad on the northern slopes. No businesses.

- Country Club — Lower Mt. Soledad on the northwest side, including the La Jolla Country Club golf course.

- Village — Also called Village of La Jolla (not to be confused with La Jolla Village) the "downtown" business district area, including most of La Jolla's shops and restaurants, and the immediately surrounding higher density and single family residential areas.

- Beach-Barber Tract — The coastal section from Windansea Beach to the Village. A few shops and restaurants along La Jolla Boulevard.

- Lower Hermosa — Coastal strip south of Beach-Barber Tract. No businesses.

- Bird Rock — Southern coastal La Jolla, and the very lowest slopes of Mt. Soledad in the area. Notable for shops and restaurants along La Jolla Boulevard, five traffic roundabouts on La Jolla Boulevard, coastal bluffs, and surfing areas just two blocks off the main drag.

- Muirlands — Relatively large area on western middle slope of Mt. Soledad. No businesses.

- La Jolla Mesa — A strip on the lower southern side of Mt. Soledad, bordering Pacific Beach. No businesses.

- La Jolla Alta — A master-planned development east of La Jolla Mesa. No businesses.

- Soledad South — Southeastern slopes of Mt. Soledad, all the way up to the top, east of La Jolla Alta.

- Muirlands West — The small neighborhood between Muirlands to the south, and Country Club to the north. No businesses.

- Upper Hermosa — Southwestern La Jolla, north of Bird Rock and east of La Jolla Blvd.

- La Jolla Village — Not to be confused with the Village (of La Jolla). In northeast La Jolla, east of La Jolla Heights, west of I-5 and south of UCSD. The neighborhood's namesake is the La Jolla Village Square shopping and residential mall, which includes La Jolla's only remaining movie theater.

Community groups

editThe La Jolla Community Planning Association[66] advises the city council, Planning Commission, City Planning Department as well as other governmental agency as appropriate in the initial preparation, adoption of, implementation of, or amendment to the General or Community Plan as it pertains to the La Jolla area as well as review specific development proposals.[67] The nonprofit La Jolla Town Council[68] represents the interests of La Jolla businesses and residents that belong to the council. The Bird Rock Community Council[69] serves the Bird Rock neighborhood, while the La Jolla Shores Association[70] serves the La Jolla Shores neighborhood. La Jolla Village Merchants Association, Inc. is a non-profit organization formed in February 2011 to manage the La Jolla Village Business Improvement District for the City of San Diego.[71]

Community organizations include Independent La Jolla,[72] a membership-based citizens group seeking to secede from the city of San Diego. Service clubs in La Jolla include Kiwanis, Rotary, La Jolla Woman's Club[73] and the Social Service League of La Jolla,[74] to name a few.

La Jolla is a subsidiary location for Chicago-based Linking Efforts Against Drugs (LEAD), a national drug-prevention organization recognized nationally for its success in reducing substance use and abuse among teens.

La Jolla is the home of InspirED, a community-focused EdTech company that supports schools in supporting their students' mental health through therapeutic services, educational opportunities, and technology.

Attractions and activities

editLa Jolla is the location of Torrey Pines Golf Course, the site each January or February of a PGA Tour event formerly known as the Buick Invitational and since 2010, called the Farmers Insurance Open.[75] Torrey Pines also hosted the 2008 and 2021 U.S. Open.[76] Nearby is the de facto nude beach, Black's Beach, and Torrey Pines Gliderport.[77]

Downtown La Jolla is noted for jewelry stores, boutiques, upmarket restaurants and hotels. Prospect Street and Girard Avenue are also shopping and dining districts.[78] The Museum of Contemporary Art, founded in 1941, is located just above the waterfront in what was originally the 1915 residence of philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps. The museum has a permanent collection with more than 3,500 post-1950 American and European works, including paintings, works on paper, sculptures, photographic art, design objects and video works.[79] The museum was renamed Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in 1990 to recognize its regional significance.

Beaches and ocean access include Windansea Beach, La Jolla Shores, La Jolla Cove and Children's Pool Beach. For many years, La Jolla has been the host of a rough water swim at La Jolla Cove.[80]

In 2011, the La Jolla Community Foundation commissioned various artists to contribute to the scenery of the town, through various murals. Some of the artists that are featured in the series are John Baldessari, Julian Opie, and Kim MacConnel. There are 11 murals in the series, all of which will be on display for two years.[81]

The La Jolla Fencing Academy opened in 2017 on Villa La Jolla Drive.[82][83][84] Among its coaches is two-time world junior saber champion, and 2023 US saber champion, Konstantin Lokhanov.[85][86]

The La Jolla Concours d'Elegance auto show is hosted at La Jolla Cove annually.[87]

Transportation

editThe San Diego Trolley light rail system has four stops on the Blue Line located in the La Jolla neighborhood:

- Nobel Drive, which serves the La Jolla Village Square shopping center in the La Jolla Village neighborhood.

- VA Medical Center, which serves the Veteran Affairs hospital of the same name next to UC San Diego.

- UC San Diego Central Campus, located in the center of the university of the same name.

- UC San Diego Health La Jolla, located near Scripps Memorial Health La Jolla, Jacobs Medical Center, the Moores Cancer Center, and the UC San Diego East Campus (contains the UC San Diego Health La Jolla campus of hospitals & medical facilities, and the Preuss School).

These four stations were opened on November 21, 2021, when the Blue Line was extended nine stops north from Old Town Transit Center to serve areas such as La Jolla Village, UC San Diego, and University City.

Education

editHigher education

editThe University of California San Diego is the center of higher education in La Jolla. The campus' name was briefly UC La Jolla during the planning stage of the university's development. UCSD includes Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the San Diego Supercomputer Center.

National University is also headquartered in La Jolla, with several academic campuses located throughout the county and the state. Among the several research institutes near UCSD and in the nearby Torrey Pines Science Park are Scripps Research Institute, the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (formerly called the La Jolla Cancer Research Foundation), La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology (LJI), and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

Other schools

editLa Jolla is served by the San Diego Unified School District. Public schools include La Jolla High School, La Jolla Elementary,[88] Muirlands Middle School,[89] Torrey Pines Elementary,[90] and Bird Rock Elementary,[91] as well as Preuss School, a public charter school. The community's prep schools are The Bishop's School, The Children's School,[92] Delphi Academy, Stella Maris Academy,[93] The Gillispie School, and the Evans School. La Jolla Country Day School is located in the nearby community of University City.

Religious institutions

editChristian:

- All Hallows Catholic Church[79]

- Assembly of God[79]

- Christian Science Church[79]

- Congregational Church (the first church built; burned down in 1915 and re-built in 1916 at 1216 Cave Street)[79]

- Barabbas Road Church[94]

- First Baptist Church

- La Jolla Christian Fellowship

- La Jolla Lutheran Church[79]

- La Jolla Presbyterian Church[79]

- La Jolla Religious Society of Friends[79]

- La Jolla United Methodist Church[79]

- Mary, Star of the Sea Catholic church[79]

- Prince Chapel by the Sea (African Methodist Episcopal Church)[79]

- St. James by-the-Sea Episcopal[79]

- St. John Church of God in Christ[79]

- Torrey Pines Christian Church[79]

- The Church Of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints San Diego California Temple

- University Lutheran Church[79]

Jewish:

Business and media

edit- La Jolla (under the fictionalized name "Esmerelda") is the setting for Raymond Chandler's final Philip Marlowe novel, Playback, published in 1958. Chandler lived in La Jolla for the previous decade. La Jolla's Hotel del Charro becomes "Rancho Descansado" in the novel. A number of landmarks described can still be found today.[95][96]

- La Jolla was home to the comic book publisher WildStorm Productions, from its founding by Jim Lee in 1993, until its closing in 2012 when DC Comics, which had purchased the publisher as an imprint in 1998, absorbed the company and moved the office to Burbank, California.[97][98][99][100]

- La Jolla is the base for the Sundt Memorial Foundation, a national organization aimed at discouraging youth from getting involved in drugs.

- La Jolla is also a subsidiary location for Chicago-based Linking Efforts Against Drugs (LEAD), a national drug-prevention organization recognized nationally for its success in reducing substance use and abuse among teens.

- La Jolla is the home of InspirED, an EdTech company that supports schools in supporting their students' mental health through therapeutic services, educational opportunities, and technology.

- La Jolla is mentioned in the Beach Boys' 1963 song Surfin' U.S.A. and in The Network's 2003 song Spike.

- "La Jolla" is the name of a song on Wilbur Soot's 2020 album Your City Gave Me Asthma.[101]

Film

edit- Laboratory scenes for the movie The Cell (2000) were filmed at The Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla.[102]

- La Jolla is one of the backdrops in the movie Traffic (2000).[103]

- Scenes for the movie The Samuel Project (2018) were filmed in La Jolla.[104]

- The movie Hemet, or the Landlady Don't Drink Tea (2023) is set in Riverside County, California, but some scenes were filmed at the director's home in La Jolla.[105]

Television

edit- La Jolla is the setting for the 2011 season of The Real World: San Diego, the twenty-sixth season of the long-running MTV reality television series.[106][107]

- The Netflix sitcom Grace and Frankie is set in La Jolla, although filming takes place in other parts of California.[108]

- Disney+'s Big Shot takes place in La Jolla.

Notable people

editLa Jolla has been the home to many notable people, including prominent scientists, business people, artists, writers, surfers and performers.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "A History of San Diego Government". Office of the City Clerk. City of San Diego. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ a b "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". 2010 Demographic Profile Data. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ "GoVisitSanDiego.com". GoVisitSanDiego.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ "Weather.com". Weather.com. June 17, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "SanDiego.org". SanDiego.org. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ US. "Mapquest". Mapquest. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "San Diego City". Sandiego.gov. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "DiscoverSD". DiscoverSD. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "La Jolla, CA Official Website". Lajollabythesea.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ Langdon 1970.

- ^ "History of La Jolla". La Jolla Playhouse, via Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Ray, Nancy (August 31, 1985). "One of La Jolla's Best-Kept Secrets Is Fun Ride". Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Gudde, Erwin Gustav (February 12, 1960). "California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names". University of California Press. Retrieved February 12, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ "An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union" (PDF). The Library of Congress. The Government of the United States. September 9, 1850. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Kucher, Karen (November 8, 2020). "Future uncertain for cottages". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c Hollins, Jeremy. "Village Memories: A Photo Essay on La Jolla's Past" (PDF). Journal of San Diego History: 295–305.

- ^ Rannells, Nathan L. (October 1958). "La Jolla No. 1". Journal of San Diego History. 4 (4).

- ^ a b "About La Jolla Elementary". San Diego Unified School District. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "About Scripps College - History". Scrippscollege.edu.

- ^ Denger, Mark J. "A Brief History of the U.S. Marine Corps in San Diego". The California State Military Museum. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Shragge, Abraham J. (Fall 2001). "Growing Up Together: The University of California's One Hundred-Year Partnership with the San Diego Region". Journal of San Diego History. 47 (4).

- ^ a b "Timeline". University of California San Diego. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "nsf.gov - Table 20 - NCSES Higher Education Research and Development: Fiscal Year 2018 - US National Science Foundation (NSF)". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Title VIII: Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity". U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ For example, when the world-famous mathematician and philosopher Jacob Bronowski came to the Salk Institute in 1963, he wanted to build a home on La Jolla Farms Road for his family. For his required character references, his family produced letters from members of Parliament, in Garson, Sue (2003). "The End of Covenant". The San Diego Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ Carless, Will (April 7, 2005). "A specter from our past: Longtime residents will always remember the stain left on the Jewel by an era of housing discrimination". LaJollaLight.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ Stratthaus, Mary Ellen (1996). "Flaw in the Jewel: Housing Discrimination Against Jews in La Jolla, California". American Jewish Historical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 18, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Synagogues in La Jolla". Google Maps. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ "Appeals court says cross on federal land is unconstitutional". CNN. January 5, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "Supreme Court won't hear Mt. Soledad cross case". San Diego Union Tribune. June 25, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Wolski, Kristi (December 12, 2013). "Federal judge says Mt. Soledad cross must come down". Fox 5 San Diego. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Davis, Kristina (December 12, 2013). "Judge: Mt. Soledad cross must come down". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "Mt. Soledad cross to stand as veterans group buys land from Defense Department". The Washington Times.

- ^ Moran, Greg (September 8, 2016). "Soledad cross case concludes, leaving memorial in place". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ^ "Her Hobby Is the Building of Cottages". San Diego Union. July 30, 1903.

- ^ "Playhouse Highlights". La Jolla Playhouse. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Ng, David (March 17, 2014). "Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego picks architect for expansion". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Sherman, Pat (July 28, 2015). "La Jolla's permit reviewers approve museum expansion". La Jolla Light. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ "map of La Jolla neighborhoods". Ruthmillsteam.com. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "San Diego City Department". Sandiego.gov. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Northern Neighborhood | Neighborhood Maps". Sandiego.gov. Archived from the original on May 6, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ Morgan, Neil. "The Building Block of Philanthropy". San Diego Magazine. May 2005. p.116.

- ^ Colla, Phil. "La Jolla Birds – Natural History Photography Blog". oceanlight.com. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ fotex (February 5, 2020). "La Jolla Kelp Forest Dive - San Diego Scuba Guide -". San Diego Scuba Guide. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "WATCH: 14-foot Great White shark circles fishing boat off La Jolla coast". ABC10 News. July 21, 2022. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ White, Brian (December 20, 2022). "Are sea lions in La Jolla attracting more sharks to the area?". cbs8.com. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ Hernandez, David (October 2, 2020). "Juvenile white sharks seen off Torrey Pines State Beach". La Jolla Light. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Shark sightings prompt public warnings near Scripps Pier". La Jolla Light. October 3, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Great White Sharks Seem to Be Around Humans All the Time: Plus a Ground Breaking Study Using Drones". The Malibu Artist, YouTube. August 23, 2023.

- ^ Schwab, Dave (January 20, 2010). "Flooding closes gym on La Jolla's Pearl Street". La Jolla Light. Archived from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Light, Elisabeth Frausto Elisabeth Frausto is a reporter for the La Jolla (April 1, 2022). "Troubled trail? Tour groups on La Jolla trail to Black's Beach draw concerns". La Jolla Light. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "Black's Beach". www.sandiego.org. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "Paragliding and Hang Gliding | Torrey Pines Gliderport". www.flytorrey.com. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "Sunset Cliffs Natural Park". Ocean Beach San Diego CA. October 25, 2013. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "La Jolla Shores Beach". CaliforniaBeaches.com. March 19, 2023.

- ^ "La Jolla Shores - Best La Jolla Beach in San Diego". San Diego Beaches and Adventures. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Dillon, Katie (February 23, 2020). "10 Best Beaches in La Jolla for Families, Surfing, & More". La Jolla Mom. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Dillon, Katie (March 15, 2020). "La Jolla Cove: Things to Do, Beach, Directions, Parking - A Local's Guide". La Jolla Mom. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Dillon, Katie (April 29, 2020). "La Jolla Seals and Sea Lions: Exactly How to Visit [Map]". La Jolla Mom. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ Zhanna (January 19, 2023). "Where to See Seals in San Diego: La Jolla's Seal Rookery and Haul-Out Places". Roads and Destinations. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ California, Everyday. "How to Swim With Sharks in La Jolla". Everyday California. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- ^ "Zipcode 92037". Plantmaps.com. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- ^ "Iranians settle on Girard Avenue to show carpets | San Diego Reader". Sandiegoreader.com. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ "Business Week, September 9, 2008". Businessweek.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008.

- ^ Showley, Roger. "La Jolla called most expensive housing market in U.S. again". Signsonsandiego.com.

- ^ "La Jolla Community Planning Association". Lajollacpa.org. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "La Jolla Community Profile". Sandiego.gov. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "La Jolla Town Council". La Jolla Town Council. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Bird Rock Community Council". Birdrock.org. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "La Jolla Shores Association". Lajollaguide.com. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "La Jolla by the Sea - The Official Website of La Jolla, California". Lajollabythesea.com. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ "Independent La Jolla". Independent La Jolla. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ Triqqer Code House. "La Jolla Women's Club". Lajollawomansclub.com. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Social Service League of La Jolla". Darlingtonhouse.com. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Farmers Insurance Open website". Farmersinsuranceopen.com. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Open Future Sites". US Open. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ Sherman, Pat (April 22, 2014). "La Jolla native chronicles Gliderport's rich history in new book". La Jolla Light. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ "La Jolla". Where. Archived from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Schaelchlin, Patricia. La Jolla: The Story of a Community 1897-1987, Friends of the La Jolla Library, San Diego, 1988

- ^ "La Jolla Rough Water Swim". Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ "Murals of La Jolla". Lajollabluebook.com. May 18, 2013.

- ^ "La Jolla Fencing Academy". www.lajollafencingacademy.com.

- ^ "A Physical Game of Chess: La Jolla Fencing Academy opens to teach swordsmanship". La Jolla Light. April 12, 2017.

- ^ "Local's La Jolla Fencing leads to championships, college success". Del Mar Times. October 18, 2017.

- ^ "Our Coaches | La Jolla Fencing Academy". www.lajollafencingacademy.com.

- ^ Longman, Jeré (July 8, 2023). "With War as a Backdrop, a Russian Fencing Drama Plays Out in the U.S." – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "La Jolla Concours d'Elegance". www.sandiego.org. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Friends of La Jolla Elementary School". Ljes.org.

- ^ "Muirlands | San Diego Unified School District". Sandiegounified.org. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ "Torrey Pines Elementary School - Home". Torreypineselementary.org.

- ^ "Bird Rock - San Diego Unified School District". Sandi.net.

- ^ "The Children's School La Jolla: Progressive Private School in San Diego -". Tcslj.org.

- ^ Stella Maris Academy, All Hallows Academy

- ^ "Barabbas Road Church in San Diego, Pacific Beach, La Jolla, CA". Barabbas Road Church in San Diego, CA.

- ^ Raymond Chandler, Playback, Houghton Mifflin, 1958

- ^ OriginallyPB (pseudonym), "Raymond Chandler's Esmerelda", Another Side of History (blog), January 16, 2015

- ^ Wells, Aaron. "Wild, wild comic art" Archived October 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, La Jolla Light, July 25, 2008

- ^ Iyoho, Charles. "Are Superheroes Fleeing La Jolla?" Archived September 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, La Jolla Patch, October 18, 2010

- ^ Phegley, Kiel. "WildStorm & Zuda Imprints Close Amidst DC Changes", Comic Book Resources, September 21, 2010

- ^ "A day of change: bye bye, WildStorm; so long, Zuda" Archived August 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Beat, September 21, 2010

- ^ La Jolla, retrieved March 21, 2023

- ^ "Where was The Cell filmed?". Giggster. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ Benninger, Michael (March 1, 2016). "Hot Shots". Pacific San Diego Magazine. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ Bell, Diane (March 27, 2017). "Old Globe actors use off-stage time to film a movie". The San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Mackin-Solomon, Ashley (January 14, 2024). "'Good type of cringey': La Jolla filmmaker to screen latest creation at Oceanside International Film Festival". La Jolla Light. Archived from the original on January 24, 2024. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ Dehnart, Andy (June 7, 2011). "Real World returning to San Diego for its 26th season". RealityBlured.com. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "MTV's Real World will screen from La Jolla, California according to San Diego Movers", Titan Movers, May 27, 2011

- ^ "Inside The Stunning Homes Of Netflix's Grace & Frankie". houseandhome.com. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

Further reading

edit- Langdon, Margaret (1970). A grammar of Diegueno: the Mesa Grande dialect. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Schaelchlin, Patricia (1988). La Jolla: The Story of a Community 1897-1987. La Jolla: Friends of the La Jolla Library.

External links

editLa Jolla, San Diego.