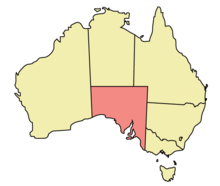

The rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Australian state of South Australia are advanced and well-established. South Australia has had a chequered history with respect to the rights of LGBT people. Initially, the state was a national pioneer of LGBT rights in Australia, being the first in the country to decriminalise homosexuality and to introduce a non-discriminatory age of consent for all sexual activity.[2][3] Subsequently, the state fell behind other Australian jurisdictions in areas including relationship recognition and parenting, with the most recent law reforms regarding the recognition of same-sex relationships, LGBT adoption and strengthened anti-discrimination laws passing in 2016 and going into effect in 2017.

LGBTQ rights in South Australia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Status | Always legal for women; legal for men since 2 October 1975 |

| Gender identity | Change of sex marker on a birth certificate requires appropriate clinical treatment since 2017[1] |

| Discrimination protections | Both state and federal law |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage since 2017; Domestic partnerships since 2007; Registered relationships since 2017 |

| Adoption | Full adoption rights since 2017 |

Since 2007, same-sex couples have been able to enter into domestic partnership agreements and since 2017 they have been able to enter into registered relationships. Changes to the law in 2017 also mean that same-sex couples have legal equity with respect to adoption, surrogacy and assisted reproductive technology rights. South Australia was the last state in the country to abolish the gay panic defence, passing reforms through its Parliament in December 2020 that went into effect in April 2021.[4][5] Hate crime laws that explicitly include "sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex characteristics" within South Australian sentencing legislation were passed and implemented in November 2021.[6] The state parliament recently passed legislation explicitly banning gay conversion therapy in October 2024.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since December 2017, after passage of the Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act 2017 in the Australian Parliament. The 2017 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey, designed to gauge public support for same-sex marriage in Australia, returned a 62.5% "Yes" response in South Australia.

Laws regarding sexual activity

editAs with other former British colonies, South Australia originally derived its criminal law from the United Kingdom. This included the prohibition of "buggery" and "gross indecency" between males.[N 1] Similarly to the United Kingdom, lesbianism was never criminalised under state law.[2]

When he was the South Australian Attorney-General in the mid-1960s, Don Dunstan was the first Australian politician that attempted to repeal homosexual offences,[7] but did not proceed at the time due to a perceived lack of public support.[2] The murder of George Duncan, a gay Australian law lecturer at the University of Adelaide on 10 May 1972, with the police accused of his death, shifted public attitudes in favour of legalising homosexuality.[8] That same year, the Dunstan Labor Government introduced a consenting adults in private defence in South Australia. This defence was later introduced as a bill by Murray Hill, father of former defence minister Robert Hill. This was a limited reform in that it retained the homosexuality offences, simply offered a narrow exception and was not intended to achieve legal parity of treatment, with Hill maintaining that homosexuality should not receive social approval.[2]

In 1975, under the premiership of Dunstan, South Australia went further with the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Amendment Act 1975[9] and became the first state or territory in Australia to offer equality under criminal law, repealing homosexual offences, decriminalising male homosexuality and providing an equal age of consent for sexual intercourse at 17 years of age.[2]

Historical conviction expungement

editSouth Australia was the first jurisdiction in Australia to develop a scheme which provides for criminal convictions of historical private consensual homosexual sexual activity to be cleared from a person's criminal record under the Spent Convictions (Decriminalised Offences) Amendment Act 2013. The act allows those with these historical convictions to apply to have them not appear on their record after a number of crime-free years. This is not a true expungement scheme because instead of being automatically erased from a criminal record upon application, the conviction is treated as "spent" if the person commits no crimes for a set number of years.[10] The legislation gained royal assent on 5 December,[11] and came into force on 22 December 2013.[12]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

editSouth Australian law allows same-sex couples to enter into marriage, domestic partnership agreements and/or registered relationships.

Same-sex marriage

editSame-sex marriage became legal in South Australia, and in the rest of Australia, in December 2017, after the Federal Parliament passed a law legalising same-sex marriage.[13]

Domestic partnerships

editSouth Australia first recognised the relationships of same-sex couples in the form of domestic partnerships. Laws which came into effect in 2007 allow same-sex couples and any two people to make a written agreement called a Domestic Partnership Agreement about their living arrangements. These laws (and others passed in 2003, 2011 and 2017) provided same-sex couples with most of the same rights as married couples, in areas such as joint finances, superannuation property rights, next of kin and hospital visitation rights and elsewhere.

The Statutes Amendment (Domestic Partners) Act 2006, which took effect on 1 June 2007,[14] amended 97 Acts, dispensing with the term "de facto" and categorising couples as "domestic partners". This meant same-sex couples and any two people who live together are now covered by the same laws. Same-sex couples may make a written agreement called a Domestic Partnership Agreement about their living arrangements. This may be prepared at any time and is legal from the time it is made, but the couples must meet other requirements, such as joint commitments, before being recognised as domestic partners. Until the bill's passage, South Australia was the only state or territory to not recognise same-sex couples in legislation.[15] The legislation passed the Parliament in December 2006.[16][17]

Under state law, equal superannuation entitlements for same-sex couples are provided for with the Statutes Amendment (Equal Superannuation Entitlements for Same Sex Couples) Act 2003. Equal rights in superannuation matters were eventually federalised in 2009.[18][19]

Further legislation in 2011, the Statutes Amendment (De Facto Relationships) Act 2011, recognised same-sex couples in asset forfeiture, property and stamp duty applications.[20]

Further legislation in 2017, the Statutes Amendment (Registered Relationships) Act 2017, recognises the domestic partnerships of same-sex couples who enter into a registered relationship (see below) in 13 additional pieces of legislation, equalising treatment for such couples in matters relating to inheritance, correctional facilities, the South Australian Supreme Court, the first home buyers grant, surveying, governor's pensions, civil liability, and conveyancing.[21] The bill passed the Parliament on 30 March and received royal assent on 26 April 2017.[21][22] The law went into effect on 1 August 2017.[23]

Civil union proposals

editSouth Australia became the first state to consider allowing civil unions for same-sex couples when MP Mark Brindal proposed the Civil Unions Bill 2004 in October 2004. Brindal said, "Same sex attracted people make invaluable contributions to society, and society can no longer afford the hypocrisy to deny them the right to formalise their relationships."[24][25]

In October 2012, independent MP Bob Such introduced a bill to the Parliament of South Australia called the Civil Partnership Bill 2012.[26][27][28][29][30][31] It failed to pass.

Registered partnerships

editSouth Australia drew media attention following the death of David Bulmer-Rizzi while on a honeymoon in Adelaide with his husband Marco.[32] Although the two men had validly married in the United Kingdom, this was not recognised under South Australian law with Bulmer-Rizzi's death certificate recording his marital status as "never married" and his father treated as next-of-kin rather than his husband.[32] Premier Jay Weatherill subsequently called Marco Bulmer-Rizzi to offer a personal apology for the state's discrimination and to promise that the law would be updated to ensure state recognition of overseas same-sex marriages in future.[32] The death certificate was also updated to acknowledge the British marriage.[33] The government subsequently sought to address the issue by introducing legislation for a relationship register.[34]

On 22 September 2016, the Relationships Register Bill 2016 was introduced to the House of Assembly.[34][35] The bill established a registry for relationships, modelled in the same way as other Australian states with domestic partnership registries. Same-sex couples married in jurisdictions which allow same-sex marriage would be able to have their relationships officially recognised under the legislation. The bill also amended legislation to allow same-sex couples equal access to altruistic surrogacy and allow for IVF treatment for single women and lesbian couples.[36][37]

Substantive debate on the bill in the lower house occurred on 15 November 2016. During committee stage, the bill was essentially divided in two; one bill (referred to as the Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy Eligibility) Bill 2016) comprising elements of the original bill which related to surrogacy and IVF regulations in the state and the other bill (referred to as the Relationships Register (No. 1) Bill 2016) comprising the remaining elements of the original bill which related to the establishment of a relationship register and the recognition of overseas same-sex marriages.[38] The bill passed the House of Assembly on 15 November and proceeded to the Legislative Council.[39] The bill was passed by the Council on 6 December.[40][41] It received royal assent on 15 December 2016, becoming the Relationships Register Act 2016, and went into effect on 1 August 2017.[42][43][44]

Adoption and parenting rights

editSame-sex adoption

editSame-sex couples have been able to adopt children in South Australia since February 2017.

Originally, the Adoption Act 1988 allowed only heterosexual couples (both married and de facto) to adopt children.[45] Single individuals were also banned from adoption in South Australia, making it the only place in Australia to have such a restriction.

The difficulties of British same-sex adoptive parents Shaun and Blue Douglas-Galley in bringing their adopted children to South Australia led them to lobby for legal reform, including a letter writing campaign to 70 politicians and an online petition that gathered 27,000 signatures.[46] In response, in July 2014, the Government of South Australia announced the formation of a committee to review its adoption laws, including whether same-sex couples and singles should be able to adopt. Submissions to the inquiry closed on 30 May 2015, though the formal recommendations of the review were not released at any stage that year.[47] Eventually, in mid-2016, the review and its recommendations were publicly released. Chief among the report's recommendations were the legalisation of adoption of children by same-sex couples and a move to allow for the amending of birth certificates to include information about the biological and adoptive parents of a child.[48][49] Around the same time, a report issued by the South Australian Law Reform Institute recommended amendments to adoption law allowing for same-sex adoption and equal access to assisted reproductive treatment for same-sex couples.[50] In August 2016, the Minister for Education and Child Development, Susan Close, said in a statement she would "soon" present a bill to Parliament amending the Adoption Act 1988, which would include a clause removing the ban on same-sex adoption. The clause would be a conscience vote matter for government members.[51][52]

On 21 September 2016, the Adoption (Review) Amendment Bill 2016 was introduced to the House of Assembly.[53] The bill would amend the Adoption Act to allow for, among other reforms, same-sex adoption and adoption of children by single persons in South Australia.[54] Debate on the bill in the lower house occurred between 2–15 November,[55] until a conscience vote was held on the legislation. The bill passed the lower house, with the clauses of the bill allowing same-sex adoption being supported by 27 votes to 16.[56] An amendment to the bill tightening the eligibility of single people to adopt was passed by 22 votes to 21; the amendment stating single people could have adoption orders granted where "the Court is satisfied that there are special circumstances justifying the making of the order".[57] The bill proceeded to the Legislative Council. On 7 December, the Council passed the bill at the third reading stage by 13 votes to 4 without amendment.[58][59] The bill received royal assent on 15 December 2016, becoming the Adoption (Review) Amendment Act 2016. Following a proclamation by the governor of South Australia on 16 February, the majority of the Act (including the parts allowing same-sex adoption) went into effect on 17 February 2017.[60][61][62]

Assisted reproductive technology and surrogacy

editSouth Australian law allows same-sex couples to have equal access to assisted reproductive treatments (ART) and altruistic surrogacy (commercial surrogacy is illegal nationwide). A law to that effect passed the Parliament in February 2017 and came into effect on 21 March 2017.

Prior to 2017, South Australia was the only jurisdiction in Australia to ban fertile single women and lesbians from accessing assisted reproductive treatments (ART). A ruling by the Supreme Court of South Australia in 1993 established that a single woman must be "medically infertile" in order to receive IVF treatment. The court found that the restriction of access to treatment on the basis of marital status (in the Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act 1988) contravened the federal Sex Discrimination Act 1984, thereby allowing infertile women of any sexual orientation access to ART.[63] The Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act 1988 was subsequently amended to include these provisions regarding infertility.[64] An attempt in May 2012 to amend the act and allow fertile women access to ART passed the upper house by 12 votes to 9, though failed in the lower house.

South Australia was also one of only two jurisdictions in Australia (the other being Western Australia) to ban altruistic surrogacy for singles and same-sex couples under the Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy) Act 2009.[65] The act presumed that the woman who gives birth to a child is the legal mother of the child, regardless of genetics. It was passed by the Parliament of South Australia on 17 November 2009.[66] An amendment introduced by Labor MP Ian Hunter which would have allowed anyone in a same-sex relationship access to surrogacy was rejected when the law was drafted in 2008.[67] Previously, the Family Relationships Act 1975 made all surrogacy arrangements in the state illegal.[68] The Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy) Act 2009 revised the Family Relationships Act by legalising altruistic surrogacy for married and de facto opposite-sex couples. The ban on commercial surrogacy remained.[69]

At the request of the state government, in May 2016 the South Australian Law Reform Institute issued a sweeping report recommending wholesale changes to assisted reproductive technology (ART) and surrogacy laws in South Australia, recommending equal access to ART services and altruistic surrogacy for same-sex couples and single women.[50] The government subsequently introduced the Relationships Registry Bill 2016 in September 2016, a bill which created a relationship registry for same-sex couples in the state and allowed equal access to surrogacy and ART services for same-sex couples and single people.[70]

On 15 November 2016, the House of Assembly split the aforementioned bill and introduced the Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy Eligibility) Bill 2016, a bill which dealt exclusively with surrogacy and assisted reproductive treatments.[71] The bill would amend several other acts so as to allow same-sex couples access to altruistic surrogacy arrangements and ensure fertile women and same-sex couples have access to assisted reproductive technology. Debate on the bill continued on 16 November, at which point the lower house removed provisions in the bill allowing single people access to altruistic surrogacy arrangements.[72] The following day, the bill passed the lower house by 25 votes to 16.[73] The bill proceeded to the Legislative Council. The bill passed the council by 14 votes to 3, though two important amendments were made to the bill at the clauses stage. Family First members introduced an amendment to allow assisted reproductive treatment providers the right to conscientiously object to providing services based on the patient's sexual orientation. Greens member Tammy Franks responded by introducing an amendment that would require any services that refused treatment to be placed on a publicly available list.[74][75] The bill returned to the House of Assembly (which by that stage had risen for the summer break) for consideration of the council's amendments. In January 2017, the report of the Allan review of the Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act 1988 (SA) concurred with the South Australian Law Reform Institute's recommendations, having conducted extensive review and consultation with community on these matters.[76] On 15 February 2017, the House agreed to an amendment moved by the socially conservative Labor member Tom Kenyon which removed the proposed requirement for those who object to providing treatment on religions or conscience grounds to be placed on a list.[77] The remainder of the bill was accepted by the House. The bill returned to the council for consideration of Kenyon's amendment, which provided its approval on 28 February.[78][79] The bill received royal assent on 15 March, becoming the Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy Eligibility) Act 2017. Following a proclamation issued by Governor Hieu Van Le, the law came into effect on 21 March 2017.[80]

The state's surrogacy laws were consolidated into the Surrogacy Act in 2019, a law which came into effect on 1 September 2020. The new law included a provision allowing "single intended parents" to pursue surrogacy in South Australia, ending the previous legislation which required the intended parents to be a two-person couple.[81]

Recognition of lesbian parents

editIn 2010, the Family Relationships (Parentage) Amendment Act 2010 was a proposed law providing partial recognition of lesbian co-mothers in same-sex relationships and their children.[82] It was introduced by Greens member Tammy Jennings following the 2010 state election in the Legislative Council and passed via a conscience vote of 14–5 on 14 November 2010. It subsequently passed in the Legislative Assembly, also via a conscience vote, by 24–15 on 10 June 2011.[83] The bill was subsequently given royal assent and became law on 23 June 2011, commencing on 15 December 2011.[84][85][86]

In June 2015, the Family Relationships (Parentage Presumptions) Amendment Bill 2015 passed the upper house. The bill abolished the 3-year relationship requirement for parentage recognition. The bill passed the lower house in February 2016 by a margin of 29–12, with both the Government and Opposition having a conscience vote.[87][88] Minor amendments to the bill in the lower house meant it had to return to the upper house for final approval, which occurred later that year. The bill received royal assent on 23 June 2016 and went into effect 3 months after being signed into law (i.e. from 23 September 2016).[89]

Discrimination protections

editHistory

editSouth Australia's Equal Opportunity Act 1984 prohibits unfair treatment of citizens due to sex, sexual orientation and gender identity, amongst a host of other aspects of life. The Act was amended in August 2016 to specifically refer to "gender identity" and "sexual orientation" as being traits protected from discrimination in employment, partnerships, accommodation, charities and numerous other areas (see 2015-16 reforms section below). Previously, the Act contained outdated definitions of what was referred to as "chosen gender" and "sexuality".[90] The monitoring body for anti-discrimination laws in the state is the South Australia Equal Opportunity Commission.[91]

Federal law also protects LGBT and intersex people in South Australia in the form of the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013.[92]

Loopholes and exemptions

editIn August 2021, it was discovered both under state and federal laws that certain loopholes and exemptions are still in force - that legally allows gay workers to be discriminated against in religious organisations (e.g. teachers in religious schools). Even as far as legally allowing to expel and suspend gay students within both religious and private schools.[93]

Gay panic defence

editUntil 1 April 2021, South Australia was the only jurisdiction in Australia to retain the gay panic defence as part of its common law. All other jurisdictions in Australia had abolished the defence from common and/or statute law, the second-last being Queensland in 2017.[94][95] On 4 May 2017, the South Australian Law Reform Institute finalised the first of its two-stage report into the defence. It found that although aspects of provocation law in South Australia which theoretically allowed a person to have a reduced sentence on the basis of a non-violent homosexual advance should be removed, no final recommendations about whether or not provocation as a defence ought to be entirely abolished should be made until the second stage of the report was completed.[96][97] The second and final stage of the report was released on 5 June 2018, several months after the state election which resulted in a change of government.[98] The Institute recommended that, subject to allowing sentencing flexibility arrangements, the defence of provocation should be abolished from South Australian law.[98][99] Attorney-General Vickie Chapman (member of the Marshall Liberal Government) responded favourably to the report, telling Parliament that "gay panic" is "simply no longer acceptable" and she will consider her response to the report's recommendations.[100]

In April 2019, Chapman promised the defence of provocation would be removed from the state's Criminal Code by the end of the year, after an extensive public consultation was undertaken.[101][102] That deadline was not met, and it was until the second half of 2020 that legislation was introduced to the Parliament.[103] The eventual legislation, which removed the defence from common law, was passed on 1 December 2020, with support from most of the members of both houses of Parliament.[4][104] The law went into effect on the 1 April 2021.[105]

In October 2021, it was reported widely that the archaic "gay panic defence" is still legally being used within South Australia in the judiciary system and courts.[106][107]

2015–16 reforms

editIn September 2015, a report released by the South Australian Law Reform Institute identified over 140 South Australian acts and regulations which discriminated (or potentially discriminated) on the grounds of sexual orientation, sex, gender identity and intersex status, and issued a number of sweeping recommendations to amend such laws.[108] The Institute followed up with a final summary report, issued in June 2016, which was specific in its focus on anti-discrimination laws in the state and the scope of religious exemptions to such laws.[109]

In response to the September 2015 report, the Parliament of South Australia introduced an omnibus LGBTI rights bill; the Statutes Amendment (Gender Identity and Equity) Bill 2016. The bill amended language used throughout South Australian law, removing gender bias and ensuring that gender identity and intersex characteristics are captured in state legislation. The bill also removed language in legislation that could have discriminated against people based on their relationship status.[110] Following the publication of the final June 2016 report, the Parliament passed the bill on 1 August. It was granted royal assent on 4 August 2016, becoming the Statutes Amendment (Gender Identity and Equity) Act 2016, and went into full effect on 8 September 2016.[111]

Transgender rights

editSouth Australia became the first state in Australia to allow individuals to alter the sex descriptor on their birth certificate without being required to undergo sex reassignment surgery or divorce if in an existing marriage. The Australian Capital Territory was the first jurisdiction in Australia to implement such a law. Appropriate clinical treatment is required instead.

On 4 August 2016, the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Amendment Bill 2016 Archived 27 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine was introduced to the lower house of Parliament. The bill would amend South Australian law by removing the requirement for transgender people to undergo sex reassignment surgery before changing their gender on their birth certificate. Instead, a person would need to consult a medical professional for a psychological assessment.[112] A conscience vote on the legislation was held on 22 September 2016, and the bill was defeated after the Speaker broke a 19–19 tie by voting against the bill. A number of supporters of the bill, including the premier, were not in attendance and had expected a vote would not be held on the legislation that day, with proponents accusing opponents of the bill of orchestrating the vote to coincide with the moment supporters of the bill would be absent from Parliament.[112][113]

A revised version of the bill was reintroduced to the lower house on 2 November 2016. The revised bill, titled the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration (Gender Identity) Amendment Bill 2016, was almost identical to the one defeated in September, except for the fact it increased the age a minor would require judicial approval for registering a change of sex or gender identity to 18 (where previously it was 16) and also mandated that the state registry would be required to retain on file all historical information preceding a change of sex or gender identity.[114][115] The bill was debated in the lower house on 16 November 2016 and passed, though an amendment was carried increasing the time required for individuals to undergo counselling before receiving an updated birth certificate.[116] On 6 December, the bill was approved in the Legislative Council by 10 votes to 7.[117][118] The bill received royal assent on 15 December 2016, becoming the Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration (Gender Identity) Amendment Act 2016 and went into effect on 23 May 2017.[119]

Implemented since 2017, all public school bathrooms and lockerrooms in South Australia must have a policy to keep transgender and intersex individuals safe.[120]

Hate crime laws

editIn November 2021, the Parliament of South Australia passed and eventually implemented explicit sentencing laws to include "sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex characteristics" to hate crimes within South Australia. The bill formally became an Act on royal assent by the Governor of South Australia within the same month and went into effect immediately.[6][121][122][123]

Conversion therapy ban

editIn October 2024, legislation was passed and enacted within South Australia - that explicitly bans sexual orientation and gender identity conversion therapy practices on individuals. The new laws are awaiting to go into legal effect.[124]

Intersex rights

editIn March 2017, representatives of Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Australia and Organisation Intersex International Australia participated in an Australian and Aotearoa/New Zealand consensus "Darlington Statement" by intersex community organizations and others.[125] The statement calls for legal reform, including the criminalization of deferrable intersex medical interventions on children, an end to legal classification of sex, and improved access to peer support.[125][126][127][128][129]

Since 1 August 2017, South Australia's Equal Opportunity Act Archived 3 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine has included anti-discrimination protections specific to intersex people. South Australia is one of just three states or territories to have such measures in their local laws, the other jurisdictions being Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory.[43][44]

Besides male and female, South Australia birth certificates and identification documents are available with a "non-binary" sex descriptor. Children born with an "indeterminate sex" may have their sex listed as "indeterminate", "intersex", or "unspecified".[130]

Summary table

edit| Same-sex sexual activity legal | (Since 1975 for men; always for women) |

| Equal age of consent | (Since 1975) |

| Equal opportunity state laws explicitly including both sexual orientation and gender identity | |

| Hate crime and sentencing legislation explicitly including sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex characteristics | (Since 2021)[6][131] |

| Intersex minors protected from invasive surgical procedures | |

| Same-sex marriage and relationship registry legally implemented | (Since 2017) |

| Full joint adoption, IVF and altruistic surrogacy access and recognition for same-sex couples | |

| Right to change legal gender without sex reassignment surgery, but requires appropriate clinical treatment | (Since 2017) |

| Gay sex criminal records expunged | / (Since 2013, records can be "spent", but not truly "expunged")[132] |

| Gay panic defence abolished | (Since 2021) |

| Conversion therapy practices banned | [133][134] |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood | / (Since 2021 3-month deferral period)[135] |

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c d e f Carbery, Graham (2010). "Towards Homosexual Equality in Australian Criminal Law: A Brief History" (PDF) (2nd ed.). Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives Inc. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Opray, Max (30 January 2016). "How Britain's same-sex marriage laws awoke South Australia to its own injustices". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ a b "South Australia becomes final state to abolish 'gay panic' murder defence". ABC News. 1 December 2020.

- ^ Jones, Ruby (22 March 2017). "South Australia becomes last state to allow gay panic defence for murder". ABC News. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "LZ". 22 November 2021.

- ^ Dunstan, Don (18 October 1968). "Talk to Newman Association" (PDF). Flinders University.

- ^ Reeves, Tim. "Duncan, George Ian (1930–1972)". Duncan, George Ian Ogilvie (1930–1972). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Amendment Act (No 66 of 1975)". classic.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ Riley, Benjamin (27 January 2014). "Community to help develop historical gay sex convictions law". Star Observer. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ Attorney General's Department. "Spent Convictions (Decriminalised Offences) Amendment Act 2013" (PDF). Government of South Australia.

- ^ Alex MacBean (28 October 2016). "Parliamentary Library Research Request". New Zealand Parliamentary Service.

- ^ "Same-sex marriage bill passes House of Representatives, paving way for first gay weddings". ABC News. 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (Domestic Partners) Act (Commencement) Proclamation 2007" (PDF). legislation.sa.gov.au. 1 June 2007.

- ^ "Votes on Homosexual Issues". South Australia, Australia, House of Assembly. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ "SA Upper House passes bill for same-sex rights (Thursday, 7 December 2006. 6:49pm (AEDT))". ABC News. ABC News Online. 7 December 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ "South Australia gays get new rights by Tony Grew (7 December 2006)". pinknews.com.au. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ Australia (4 February 2010). "Commonwealth Powers (De Facto Relationships) Act 2009". Legislation.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (De Facto Relationships) Act 2011" (PDF). 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Legislative Tracker: Statutes Amendment (Registered Relationships) Bill 2017". Parliament of South Australia. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (Registered Relationships) Act 2017" (PDF). legislation.sa.gov.au. 26 April 2017.

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (Registered Relationships) Act (Commencement) Proclamation" (PDF). legislation.sa.gov.au. 1 August 2017.

- ^ "South Australian MP fights for more gay rights (15 October 2004)". Pink Guide. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ^ "South Australia to consider same-sex civil unions (19 October 2004)". Fridae.com. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ^ Australia. "Civil Partnerships Bill 2012". Legislation.sa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "New civil partnerships bill". Star Observer. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "South Australian Parliament receives Private Member's Bill proposing civil unions for all". Herald Sun. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "The latest entertainment news for Australia's LGBTIQ community". Gay News Network. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ Gayapolis, Inc. (23 September 2012). "Australia: Civil Unions Proposed in South Australia". Gayapolis.com. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "Same-sex marriage alternative Bill introduced to Parliament". The Advertiser. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Davies, Caroline; Hunt, Elle (21 January 2016). "Premier apologises to bereaved Briton whose same-sex marriage was not recognised". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "SA amends death certificate to recognise British man's same-sex marriage". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 January 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ a b Hunt, Elle (21 September 2016). "South Australia introduces bill to recognise same-sex marriages". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "South Australian Legislation: Relationships Register Bill 2016". Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "South Australia finally moves to change laws to recognise oversees same-sex marriages". Gay News Network. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "SA govt introduce bill to legally recognise same-sex relationships". Out in Perth. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Tracker: Relationships Register (No 1) Bill 2016". Parliament of South Australia. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ "House of Assembly Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

Refer to pages 7730-7741

- ^ "Legislative Council Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

Refer to pp. 5809-5821

- ^ "Marco Bulmer-Rizzi welcomes South Australia's Relationship Register". ABC News. 7 December 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Administrative Arrangements (Administration of Relationships Register Act) Proclamation 2017" (PDF). legislation.sa.gov.au. 1 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Australian state recognizes same-sex marriages, introduce intersex anti-discrimination measures". Gay Star News. 1 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b "South Australia introduces relationship recognition for same-sex couples and anti-discrimination protections for intersex people". Human Rights Law Centre. 1 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Adoption Act 1988 (Prior to the 2016 amendments which legalised same-sex adoption)" (PDF). 31 December 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Jacques, Oliver (23 November 2016). "Gay adoption set to be legal in every Australian state". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Foster parents set to have more power over everyday decisions about children in their care". The Advertiser. 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Adoption Act review". Your Say SA. 30 May 2015. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016.

- ^ "Adoption Act 1988 (SA) Review" (PDF). Social and Policy Studies at Flinders University (in conjunction with the South Australian Government). 30 May 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Rainbow Families: Equal Recognition of Relationships and Access to Existing Laws Relating to Parentage, Assisted Reproductive Treatment and Surrogacy" (PDF). South Australian Law Reform Institute. 1 May 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ Liz Walsh (5 August 2016). "Gay dads Shaun and Blue Douglas-Galley push to change South Australia's adoption laws". The Advertiser.

The bill will include a clause to remove discrimination against same-sex couples adopting...will be a matter of a conscience vote for government members...Shaun has heard whispers that that conscience vote could be coming as early as September.

- ^ Liz Walsh (20 September 2016). "Child Protection Minister Susan Close's Bill would allow same-sex couples to apply for adoption in SA". The Advertiser.

- ^ "South Australian Legislation: Adoption (Review) Amendment Bill 2016". Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ "Hansard: 21 September 2016". Parliament of South Australia (House of Assembly). 21 September 2016.

Refer to pages 6880-6882 for full summary of amendments

- ^ "Legislative Tracker: Adoption (Review) Amendment Bill 2016". Parliament of South Australia. 21 September 2016. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ Caroline Winter (15 November 2016). "South Australian MPs' conscience vote backs allowing same-sex couples to adopt". ABC News.

- ^ "House of Assembly Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

Refer to pages 7796, 7797, 7799 and 7802

- ^ "South Australia Passes New Law Allowing Gay Couples To Adopt Children". BuzzFeed. 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Council Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

Refer to pp. 5907-5920

- ^ "Adoption (Review) Amendment Act (Commencement) Proclamation 2017" (PDF). Legislation.sa.gov.au. 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Adoption equality now a reality for South Australians". Human Rights Law Centre. 17 February 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- ^ Waldhuter, Lauren (17 February 2017). "Same-sex couples welcome introduction of adoption equality in SA". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Yfantidis v Dr Jones & Flinders Medical Centre [1993] SASC 4337, (1993) 61 SASR 458 (15 December 1993), Supreme Court (SA).

- ^ "Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act 1988" (PDF). Legislation South Australia. 26 November 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy) Act 2009" (PDF). 26 November 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "SA legalises surrogate birth". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 November 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ Vaughan, Joanna (19 June 2008). "Gay couples lose surrogacy access". The Advertiser. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- ^ "Family Relationships Act 1975" (PDF). 1 June 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Australia. "Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy) Act 2009". Legislation.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "Relationships Registry Bill 2016" (PDF). Parliament of South Australia. 22 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Tracker: Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy Eligibility) Bill 2016". Parliament of South Australia. 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "House of Assembly Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

Refer to pages 7911-7920

- ^ "House of Assembly Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

Refer to pages 8068-8076

- ^ "Same-sex couples in South Australia set to get adoption and surrogacy rights". ABC News. 7 December 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Council Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

Refer to pp. 5920-5926 & 5953-5960

- ^ Sonia Allan, Report on the Review of the Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act 1988 (SA) (2017), Recommendation 49.

- ^ "House of Assembly Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 15 February 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

Refer to pp. 8504-8507

- ^ "Legislative Council Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

Refer to pp. 6126

- ^ "Same-sex couples in South Australia to have access to IVF and unpaid surrogacy". Human Rights Law Centre. 28 February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (Surrogacy Eligibility) Act (Commencement) Proclamation 2017" (PDF). legislation.sa.gov.au. 21 March 2017.

- ^ "South Australia Surrogacy Law Reform Update". sarahjefford.com. 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Family Relationships (Parentage) Amendmeng Act 2010 text". Archived from the original on 28 March 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Hughes, Ron (9 June 2011). "SA parenting bill passes with large majority". SX. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Consumer and Business Services - Office of Consumer and Business Services South Australia" (PDF). Ocba.sa.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "Family Relationships (Parentage) Amendment Act 2011" (PDF). 23 June 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Australia. "Acts of the Parliament of South Australia". Legislation.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ "South Australian female co-parents to be recognised on child's birth certificate". Star Observer. 11 February 2016.

- ^ "New laws for lesbian parents in SA". 9News. 4 June 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Family Relationships (Parentage Presumptions) Amendment Act 2016" (PDF). Parliament of South Australia. 23 June 2016.

- ^ "SA Equal Opportunity Commission: Chosen Gender". Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Homepage". Equal Opportunity Commission. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "New Protection". Australian Human Rights Commission. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Premier Steven Marshall against discrimination of gay teachers | OUTInPerth | LGBTQIA+ News and Culture". 29 August 2021.

- ^ "South Australia becomes last state to allow gay panic defence". ABC News. 22 March 2017.

- ^ "The 'Gay Panic Defence' Probably Can't Be Used in South Australia". BuzzFeed News. 24 March 2017.

- ^ "Murder defence should not be linked to 'gay panic'". The University of Adelaide. 4 May 2017. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017.

- ^ "The Provoking Operation of Provocation: Stage 1" (PDF). South Australian Law Reform Institute. 4 May 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2018.

- ^ a b "The Provoking Operation of Provocation: Stage 2" (PDF). 5 June 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "South Australian Government set to repeal gay panic defence". Human Rights Law Centre. 5 June 2018.

- ^ "'Gay panic' defence under fire again in SA, along with mandatory murder terms". ABC News. 5 June 2018.

- ^ Barber, Laurence (9 April 2019). "South Australia To Finally Scrap 'Gay Panic' Defence by the End of the Year". Star Observer.

- ^ "SA to dump provocation defence". Mandurah Mail. 9 April 2019.

- ^ Nielsen, Ben (2 June 2020). "SA led the way for many reforms, so why is 'gay panic' still a defence?". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Scherer, Jennifer (2 December 2020). "South Australia becomes the last state to scrap 'gay panic' murder defence". SBS News.

- ^ "Statutes Amendment (Abolition of Defence of Provocation and Related Matters) Act (Commencement) Proclamation 2021". legislation.sa.gov.au. 22 November 2021.

- ^ "Adelaide man who bashed and robbed victim blames 'gay advance'". 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Adelaide Man Accused of Stabbing Death Claims Victim Had 'Acted Gay'". 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Audit Paper: Discrimination on the grounds of gender identity, sexual orientation and intersex status under South Australian legislation" (PDF). South Australian Law Reform Institute. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ "'Lawful Discrimination': Exceptions under the Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA) to allow discrimination on the grounds of gender identity, sexual orientation and intersex status" (PDF). South Australian Law Reform Institute. 1 June 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "South Australia changing discriminatory LGBTI laws". Star Observer. 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Commencement provisions of the Statutes Amendment (Gender Identity and Equity) Bill 2016" (PDF). Parliament of South Australia. 8 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Jay denies rift after colleagues help kill 'culture war' gender bill". In Daily. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Gender identity bill fails to pass South Australian Parliament". ABC News. 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Assembly Hansard (refer to pages 7554-6)". Parliament of South Australia. 2 November 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Tracker: Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration (Gender Identity) Amendment Bill 2016". Parliament of South Australia. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ "House of Assembly Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

Refer to pages 7832-7842 and 7906-7911

- ^ "Landmark Transgender Rights Bill Passes in South Australia, Nixed in Victoria". BuzzFeed. 6 December 2016.

- ^ "Legislative Council Hansard". Parliament of South Australia. 6 December 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

Refer to pp. 5853-5861

- ^ "Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration (Gender Identity) Amendment Act (Commencement) Proclamation 2017" (PDF). Legislation.sa.gov.au. 23 May 2017.

- ^ "SA schools introduce transgender, intersex policy". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 5 January 2017.

- ^ https://www.riverineherald.com.au/national/2021/08/26/5011329/new-laws-proposed-for-sa-hate-crimes [dead link]

- ^ "New laws proposed for SA hate crimes". 26 August 2021.

- ^ "LZ". 22 November 2021.

- ^ "LZ". 22 November 2021.

- ^ a b Androgen Insensitivity Support Syndrome Support Group Australia; Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand; Organisation Intersex International Australia; Black, Eve; Bond, Kylie; Briffa, Tony; Carpenter, Morgan; Cody, Candice; David, Alex; Driver, Betsy; Hannaford, Carolyn; Harlow, Eileen; Hart, Bonnie; Hart, Phoebe; Leckey, Delia; Lum, Steph; Mitchell, Mani Bruce; Nyhuis, Elise; O'Callaghan, Bronwyn; Perrin, Sandra; Smith, Cody; Williams, Trace; Yang, Imogen; Yovanovic, Georgie (March 2017), Darlington Statement, archived from the original on 22 March 2017, retrieved 21 March 2017 Alt URL

- ^ Copland, Simon (20 March 2017). "Intersex people have called for action. It's time to listen". Special Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ Jones, Jess (10 March 2017). "Intersex activists in Australia and New Zealand publish statement of priorities". Star Observer. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ Power, Shannon (13 March 2017). "Intersex advocates pull no punches in historic statement". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ Sainty, Lane (13 March 2017). "These Groups Want Unnecessary Surgery on Intersex Infants To Be Made A Crime". BuzzFeed Australia. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ "New requirements for registering a change of sex or gender identity". Consumer and Business Services. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "LZ". 22 November 2021.

- ^ Sainty, Lane (14 January 2016). "Some States Are Holding Out Against Erasing Historic Gay Sex Convictions". Buzzfeed. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "LZ". 22 November 2021.

- ^ (Not yet in effect)[2]

- ^ "FAQ". Australian Red Cross Lifeblood. Retrieved 10 May 2021.