Krzysztof Eugeniusz Penderecki (Polish: [ˈkʂɨʂtɔf pɛndɛˈrɛt͡skʲi] ⓘ; 23 November 1933 – 29 March 2020) was a Polish composer and conductor. His best-known works include Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima,[1] Symphony No. 3, his St Luke Passion, Polish Requiem, Anaklasis and Utrenja. His oeuvre includes five operas, eight symphonies and other orchestral pieces, a variety of instrumental concertos, choral settings of mainly religious texts, as well as chamber and instrumental works.[1][better source needed]

Krzysztof Penderecki | |

|---|---|

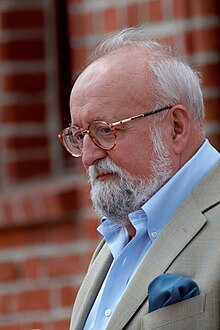

Penderecki in 2008 | |

| Born | Krzysztof Eugeniusz Penderecki 23 November 1933 |

| Died | 29 March 2020 (aged 86) Kraków, Poland |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Born in Dębica, Penderecki studied music at Jagiellonian University and the Academy of Music in Kraków. After graduating from the academy, he became a teacher there and began his career as a composer in 1959 during the Warsaw Autumn festival. His Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima for string orchestra and the choral work St. Luke Passion have received popular acclaim. His first opera, The Devils of Loudun, was not immediately successful. In the mid-1970s, Penderecki became a professor at the Yale School of Music.[2] From the mid-1970s his composition style changed, with his first violin concerto focusing on the semitone and the tritone. His choral work Polish Requiem was written in the 1980s and expanded in 1993 and 2005.

Penderecki won many prestigious awards, including the Prix Italia in 1967 and 1968; the Wihuri Sibelius Prize of 1983; four Grammy Awards in 1987, 1998 (twice), and 2017; the Wolf Prize in Arts in 1987; and the University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition in 1992.[3] In 2012, Sean Michaels of The Guardian called him "arguably Poland's greatest living composer".[4] In 2020 the composer's Alma Mater, the Academy of Music in Kraków, was named after Krzysztof Penderecki.[5]

Career

edit1933–1958: early years

editPenderecki was born on 23 November 1933 in Dębica, the son of Zofia and Tadeusz Penderecki, a lawyer. His grandfather Michał Penderecki was a native of Tenetnyky village near Rohatyn (now Ukraine)[6] and belonged to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church.[7] He married Stefania Szylkiewicz of Armenian origin[7] from Stanislau (now Ivano-Frankivsk in Ukraine)[8] and they later moved to Dębica. The rest of the Penderecki family avoided Polonisation and some still live in their ancestral village.[9] Krzysztof met them upon his visits to Ukraine in the 1990s.[6] On his mother's side his grandfather, Robert Berger, was a highly talented painter and director of the local bank at the time of Penderecki's birth; Robert's father Johann, a German Protestant, moved to Dębica from Breslau (now Wrocław) in the mid-19th century. Out of love for his wife, he subsequently converted to Catholicism.[8][10]

Krzysztof was the youngest of three siblings; his sister, Barbara, was married to a mining engineer, and his older brother, Janusz, was studying law and medicine at the time of his birth. Tadeusz was a violinist and also played piano.[10]

The Second World War broke out in 1939; Penderecki's family moved out of their apartment, for the Ministry of Food was to operate there. After the war, Penderecki began attending grammar school in 1946. He began studying the violin under Stanisław Darłak, Dębica's military bandmaster who organized an orchestra for the local music society after the war. Upon graduating from grammar school, Penderecki moved to Kraków in 1951, where he attended Jagiellonian University.[11]

He studied violin with Stanisław Tawroszewicz and music theory with Franciszek Skołyszewski. In 1954, Penderecki entered the Academy of Music in Kraków and, having finished his studies on violin after his first year, focused entirely on composition. Penderecki's main teacher there was Artur Malawski, a composer known for his choral and orchestral works, as well as chamber music and songs. After Malawski's death in 1957, Penderecki took further lessons with Stanisław Wiechowicz, a composer primarily known for his choral works.[12] At the time, the 1956 overthrow of Stalinism in Poland lifted strict cultural censorship and opened the door to a wave of creativity.[13]

1958–1962: first compositions

editUpon graduating from the Academy of Music in Kraków in 1958, Penderecki took up a teaching post at the academy. His early works show the influence of Anton Webern and Pierre Boulez (Penderecki was also influenced by Igor Stravinsky). Penderecki's international recognition began in 1959 at the Warsaw Autumn with the premieres of the works Strophen, Psalms of David, and Emanations, but the piece that truly brought him to international attention was Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima (see threnody and atomic bombing of Hiroshima), written in 1960 for 52 string instruments. In it, he makes use of extended instrumental techniques (for example, playing behind the bridge, bowing on the tailpiece). There are many novel textures in the work, which makes extensive use of tone clusters. He originally titled the work 8' 37", but decided to dedicate it to the victims of Hiroshima.[14]

Fluorescences followed a year later; it increases the orchestral density with more wind and brass, and an enormous percussion section of 32 instruments for six players, including a Mexican güiro, typewriters, gongs and other unusual instruments. The piece was composed for the Donaueschingen Festival of contemporary music of 1962, and its performance was regarded as provocative and controversial. Even the score appeared revolutionary; the form of graphic notation that Penderecki had developed rejected the familiar look of notes on a staff, instead representing music as morphing sounds.[13] His intentions at this stage were quite Cagean: 'All I'm interested in is liberating sound beyond all tradition'.[15]

Another noteworthy piece of this period is the Canon for 52 strings and 2 tapes. This is in a similar style to other pieces in the late 1950s in its use of sound masses, dramatically juxtaposed with traditional means although the use of standard techniques or idioms is often disguised or distorted. Indeed, the Canon brings to mind the choral tradition and indeed the composer has the players sing, albeit with the performance indication of bocca chiusa (with closed mouth) at various points; nevertheless, Penderecki uses the 52 'voices' of the string orchestra to play in massed glissandi and harmonics at times – this is then recorded by one of the tapes for playback later on in the piece. It was performed at the Warsaw Autumn Festival in 1962 and caused a riot although curiously the rioters were young music students and not older concertgoers.[16]

At the same time, he started composing music for theater and film. The first theater performance with Penderecki's music was Złoty kluczyk (Golden Little Key) by Yekaterina Borysowa directed by Władysław Jarema (premiered on 12 May 1957 in Krakow at the "Groteska" Puppet Theater). In 1959, at the Cartoon Film Studio in Bielsko-Biała, he composed the music for the first animated film, Bulandra i diabeł (Coal Miner Bulandra and Devil), directed by Jerzy Zitzman and Lechosław Marszałek.[17]

In 1959, he wrote the score for Jan Łomnicki's first short fiction film, Nie ma końca wielkiej wojny (There is no End to the Great War, WFDiF Warszawa). In the following years he created over twenty original musical settings for dramatic and over 40 puppet performances, and composed original music for at least eleven documentary and feature films as well as for twenty-five animated films for adults and children.[18]

The St. Luke Passion

edit| Year | Song title | Work | Instrumentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968: | "Miserere mei, Deus" ⓘ |

Saint Luke Passion | Chorus |

The large-scale St. Luke Passion (1963–66) brought Penderecki further popular acclaim, not least because it was devoutly religious, yet written in an avant-garde musical language, and composed within Communist Eastern Europe. Various different musical styles can be seen in the piece. The experimental textures, such as were employed in the Threnody, are balanced by the work's Baroque form and the occasional use of more traditional harmonic and melodic writing. Penderecki makes use of serialism in this piece, and one of the tone rows he uses includes the BACH motif, which acts as a bridge between the conventional and more experimental elements. The Stabat Mater section toward the end of the piece concludes on a simple chord of D major, and this gesture is repeated at the very end of the work, which finishes on a triumphant E major chord. These are the only tonal harmonies in the work, and both come as a surprise to the listener; Penderecki's use of tonal triads such as these remains a controversial aspect of the work.[19]

Penderecki continued to write sacred music. In the early 1970s he wrote a Dies irae, a Magnificat, and Canticum Canticorum Salomonis (Song of Songs) for chorus and orchestra.[15]

De Natura Sonoris and other pieces in the 1960s and early 1970s

editPenderecki's preoccupation with sound culminated in De Natura Sonoris I (1966), which frequently calls upon the orchestra to use non-standard playing techniques to produce original sounds and colours. A sequel, De Natura Sonoris II, was composed in 1971: with its more limited orchestra, it incorporates more elements of post-Romanticism than its predecessor. This foreshadowed Penderecki's renunciation of the avant-garde in the mid-1970s, although both pieces feature dramatic glissandos, dense clusters, use of harmonics, and unusual instruments (the musical saw features in the second piece).

In 1968 Penderecki received the State Prize 1st class.[20] During the jubilee of the People's Republic of Poland he received the Commander's Cross (1974)[21] and the Knight's Cross of Order of Polonia Restituta (1964).[22]

Towards the end of the decade, Penderecki received a commission to write for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the United Nations. The result was Kosmogonia, a piece of twenty minutes for 3 soloists (soprano, tenor, bass), mixed choir and orchestra. The Los Angeles Philharmonic premiered the piece on 24 October 1970 with Zubin Mehta as conductor and Robert Nagy as tenor. The piece uses texts from ancient writers Sophocles and Ovid in addition to contemporary statements from Soviet and American astronauts to musically explore the idea of the cosmos.[23]

1970s–2020: later years

editIn the mid-1970s, while he was a professor at the Yale School of Music,[24] Penderecki's style began to change. The Violin Concerto No. 1 largely leaves behind the dense tone clusters with which he had been associated, and instead focuses on two melodic intervals: the semitone and the tritone. This direction continued with the Symphony No. 2 (1980), which is harmonically and melodically quite straightforward; the symphony is sometimes referred to as the "Christmas Symphony" due to the opening phrase of the Christmas carol Silent Night appearing three times during the work.[25]

Penderecki explained this shift by stating that he had come to feel that the experimentation of the avant-garde had gone too far from the expressive, non-formal qualities of Western music: 'The avant-garde gave one an illusion of universalism. The musical world of Stockhausen, Nono, Boulez and Cage was for us, the young – hemmed in by the aesthetics of socialist realism, then the official canon in our country – a liberation...I was quick to realise however, that this novelty, this experimentation, and formal speculation, is more destructive than constructive; I realised the Utopian quality of its Promethean tone'. Penderecki concluded that he was 'saved from the avant-garde snare of formalism by a return to tradition'.[15] Penderecki wrote relatively little chamber music. However, compositions for smaller ensembles range in date from the start of his career to the end, reflecting the changes his style of writing has undergone.[26]

In 1975 the Lyric Opera of Chicago asked him to write a work to commemorate the US Bicentennial in 1976; this became the opera Paradise Lost Owing to delays to the project, however, it did not see its premiere until 1978. The music continued to illustrate Penderecki's move away from avant-garde techniques. It is tonal music, and the composer explained: "This is not music by the angry young man I used to be".[27]

In 1980, Penderecki was commissioned by Solidarity to compose a piece to accompany the unveiling of a statue at the Gdańsk shipyards to commemorate those killed in anti-government riots there in 1970. Penderecki responded with Lacrimosa, which he later expanded into one of the best-known works of his later period, the Polish Requiem (1980–84, 1993, 2005). Later, he tended towards more traditionally conceived tonal constructs, as heard in works such as the Cello Concerto No. 2 and the Credo, which received the Grammy Award for best choral performance for the world-premiere recording made by the Oregon Bach Festival, which commissioned the piece. The same year, Penderecki was awarded the Prince of Asturias Prize in Spain, one of the highest honours given in Spain to individuals, entities, organizations or others from around the world who make notable achievements in the sciences, arts, humanities, or public affairs. Invited by Walter Fink, he was the eleventh composer featured in the annual Komponistenporträt of the Rheingau Musik Festival in 2001. He conducted the Credo on the occasion of the 70th birthday of Helmuth Rilling, 29 May 2003.[28] Penderecki received an honorary doctorate from the Seoul National University, Korea, in 2005 and the University of Münster, Germany, in 2006. His notable students include Chester Biscardi and Walter Mays.

In celebration of his 75th birthday, he conducted three of his works at the Rheingau Musik Festival in 2008, among them Ciaccona from the Polish Requiem.[29]

In 2010, he worked on an opera based on Phèdre by Racine for 2014, which was never realized,[30] and expressed his wish to write a 9th symphony.[31] In 2014, he was engaged in the creation of a choral work to coincide with the Armenian genocide centennial.[32] In 2018, he conducted Credo in Kyiv at the 29th Kyiv Music Fest, marking the centenary of Polish independence.[33]

Personal life

editPenderecki had three children, firstly a daughter Beata with pianist Barbara Penderecka (née Graca), whom he married in 1954; they later divorced.[34] He then had a son, Łukasz (b. 1966), and daughter, Dominika (b. 1971), with his second wife, Elżbieta Penderecka (née Solecka), whom he married on 19 December 1965.[35] He lived in the Kraków suburb of Wola Justowska. He was also a keen gardener, and established a 16-hectare arboretum near his manor house in Lusławice.[36][37]

Penderecki died at his home in Kraków, Poland, on 29 March 2020, after a long illness.[38] He was buried at the National Pantheon in Kraków on 29 March 2022.[39]

Legacy and influence

editIn 1979, a bronze bust by artist Marian Konieczny honouring Penderecki was unveiled in The Gallery of Composers' Portraits at the Pomeranian Philharmonic in Bydgoszcz.[40] His monument is located on the Celebrity Alley at the Scout Square (Skwer Harcerski) in Kielce.[41]

The Led Zeppelin guitarist and founding member Jimmy Page was an admirer of the composer's groundbreaking work Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima during his teenage years. This would be reflected later by Page's use of the violin bow on his guitar.[42]

The composer and Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood cited Penderecki as a major influence.[43] For Radiohead's 1997 album OK Computer, Greenwood wrote a part for 16 stringed instruments playing quarter tones apart, inspired by Penderecki.[44] Greenwood visited Penderecki in 2012 and wrote a work for strings, 48 Responses to Polymorphia, which Penderecki conducted in various performances throughout Europe.[43] Penderecki credited Greenwood for introducing his music to a new generation.[43]

Works

editPenderecki's compositions include operas, symphonies, choral works, as well as chamber and instrumental music.

Film and television scores

editKrzysztof Penderecki composed between 1959 and 1968 original music for at least eleven documentary and feature films as well as for twenty-five animated films for adults and children.[45]

Some of Penderecki's music has been adapted for film soundtracks. The Exorcist (1973) features his String Quartet and Kanon For Orchestra and Tape; fragments of the Cello Concerto and The Devils of Loudun. Writing about The Exorcist, the film critic for The New Republic wrote that 'even the music is faultless, most of it by Krzysztof Penderecki, who at last is where he belongs'.[46] Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980) features six pieces of Penderecki's music:[1] Utrenja II: Ewangelia, Utrenja II: Kanon Paschy, The Awakening of Jacob, De Natura Sonoris No. 1, De Natura Sonoris No. 2 and Polymorphia.[47] David Lynch has used Penderecki's music in the soundtracks of the films Wild at Heart (1990), Inland Empire (2006), and the TV series Twin Peaks (2017). In the film Fearless (1993) by Peter Weir, the piece Polymorphia was once again used for an intense plane crash scene, seen from the point of view of the passenger played by Jeff Bridges. Penderecki's Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima was also used during one of the final sequences in the film Children of Men (2006).[1] Penderecki composed music for Andrzej Wajda's 2007 Academy Award nominated film Katyń, while Martin Scorsese's Shutter Island (2010) featured his Symphony No. 3 and Fluorescences.

Honors and awards

edit- 1959: 2nd Competition for Young Polish Composers in Warsaw organised by the Polish Composers' Union – Penderecki was awarded the top three prizes for the works he anonymously submitted: Stanzas, Emanations, and Psalms of David;[48]

- 1961: Prize of the UNESCO International Tribune of Composers in Paris for Threnody;[49]

- 1966: Grand Art Prize of North Rhine-Westphalia for St. Luke Passion;[50]

- 1967: Prix Italia for the St. Luke Passion;[50] Sibelius Gold Medal;[48]

- 1968: Prix Italia for the Dies Irae in memory of the victims of Auschwitz;[50] Grammy Trustees Award for significant contributions, other than performance, to the field of recording;[51]

- 1972: City of Kraków Award;[48]

- 1977: Herder Prize (Germany/Austria)[52]

- 1978: Prix Arthur Honegger for Magnificat (France)[50]

- 1983: Wihuri Sibelius Prize (Finland);[53] Polish National Award[54]

- 1985: Premio Lorenzo Magnifico (Italy)[50][54]

- 1987: Wolf Prize in Arts (Israel);[54] Grammy for Best Contemporary Composition[55]

- 1990: Grand Cross of Merit of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany;[50][54] Chevalier de Saint Georges;[48]

- 1992: University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition for Adagio – 4 Symphony;[56] Austrian Medal for Science and Art;[48]

- 1993: distinguished Citizen Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study at Indiana University, Bloomington, Prize of the International Music Council / UNESCO for Music;[54] Cultural Merit of the Principality of Monaco[54]

- 1995: Member of the Royal Irish Academy of Music (Dublin);[48] honorary citizen of Strasbourg;[48] Primetime Emmy Award of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences;[48] Pro Baltica Prize[52]

- 1996: Primetime Emmy Award of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (France)[52]

- 1998: Grammy for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance;[55] Composition Prize for the Promotion of the European economy, Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters;[48] corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts, Munich;[48] Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (Lithuania)[48]

- 1999: music Prize of the City of Duisburg (Germany);[48] Honorary Board of the Vilnius Festival '99[48]

- 2000: Cannes Classical Award as "Living Composer of the Year";[48] honorary member of the Society of Friends of Music in Vienna;[57] Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic;[48]

- 2001: Prince of Asturias Award for Art (Spain);[58] Grammy for Best Choral Performance for Credo;[48] Honorary Professor of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts[48]

- 2002: State Prize of North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany), Romano Guardini Prize[59]

- 2003: Grand Gold Decoration for Services to the Republic of Austria;[60] Preis der Europäischen Kirchenmusik (Germany), Freedom of Dębica, Eduardo M. Torner Medal of the Conservatorio de Musica del Principado Asturias in Oviedo, Spain; honorary director of the Choir of the Prince of Asturias Foundation, Honorary President of the Apayo a la Creación Musical, Judaica Foundation Medal;

- 2004: Praemium Imperiale – Music (Japan)[52]

- 2005: Order of the White Eagle (Poland);[61] Gold Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis[62]

- 2006: Order of the Three Stars (Latvia)[63]

- 2008: Polish Academy Award for Best Film Score for Katyn, Commander of the Order of the Three Stars (Latvia), Order of Bernardo O'Higgins (Chile), Golden Medal of the Minister of Culture (Armenia), Commander of the Order of the Lion of Finland;[64] Thorunium Medal[65]

- 2009: Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg;[66] Merit of Armenia[48]

- 2011: Viadrina Prize for contributions to Polish-German cooperation (Viadrina European University, Frankfurt);[67][68] Grand Cross of the Order pro Merito Melitensi (Malta)[50]

- 2012: Paszport Polityki Award[69]

- 2014: Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana, 1st Class (Estonia)[70]

- 2015: Per Artem ad Deum Medal[71]

- 2017: Grammy for Best Choral Performance;[55] New Culture of New Europe Award at the Krynica Economic Forum.[72]

Penderecki was an honorary doctor and honorary professor of several universities: Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., University of Glasgow, Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory, Fryderyk Chopin Music Academy in Warsaw, Seoul National University, Universities of Rochester, Bordeaux, Leuven, Belgrade, Madrid, Poznan and St. Olaf College (Northfield, Minnesota), Duquesne University, Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, University of Pittsburgh (PA), University of St. Petersburg, Beijing Conservatory, Yale University and Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität in Münster (Westphalia) (2006 Faculty of Arts).[73]

He was an honorary member of the following academies and music companies: Royal Academy of Music (London), Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (Rome), Royal Swedish Academy of Music (Stockholm), Academy of Arts (London), Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes (Buenos Aires), the Society of Friends of Music in Vienna, Academy of Arts in Berlin, Académie Internationale de Philosophie et de l'Art in Bern, and the Académie Nationale des Sciences, Belles-lettres et Arts in Bordeaux.[54] In 2009, he became an honorary citizen of the city of Bydgoszcz.[74]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Levenson, Eric (29 March 2020). "Krzysztof Penderecki, composer of works in 'The Exorcist' and 'The Shining,' dies at 86". CNN. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Чим унікальна краківська музична академія та хто такий Криштоф Пендерецький - krakow1.one". 28 November 2022.

- ^ "1992 – Krzysztof Penderecki – Grawemeyer Awards". Grawemeyer.org. 20 July 1992.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (23 January 2012). "Jonny Greenwood reveals details of Krzysztof Penderecki collaboration". The Guardian.

- ^ "Zmiana nazwy Akademii Muzycznej w Krakowie". Dziennik Ustaw (in Polish). 16 December 2020.

- ^ a b Roman Rewakowicz’s memoir about Krzysztof Penderecki

- ^ a b "Penderecki on 'aiming for the unreachable'". Dw.com.

- ^ a b Lech, Filip (18 November 2018). "Mistrz". Wprost (in Polish). Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ (LXIX) Wschodnie korzenie Krzysztofa Pendereckiego

- ^ a b Schwinger, p. 16.

- ^ Schwinger, p. 17.

- ^ Schwinger, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Monastra, Peggy. "Krzysztof Penderecki's Polymorphia and Fluorescences" (PDF). Moldenhauer Archives, Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- ^ Thomas (2008), p. 165

- ^ a b c Tomaszewski, Mieczyslaw (2000). "Orchestral Works Vol 1 Liner Notes". Amazon.

- ^ Jakelski, Lisa (2017). Making new music in Cold War Poland: the Warsaw Autumn Festival, 1956–1968. University of California Press. pp. 80–83. ISBN 978-0-520-29254-3.

- ^ "Bulandra i diabeł". telemagazyn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "O projekcie – Muzyczny Ślad Krakowa" (in Polish). Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Walter, Meinrad (2002). "Avantgarde mit menschlichem Antlitz". Herder Korrespondenz (in German). 2002 (10): 507–512. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Dziennik Polski, rok XXIV, nr 172 (7599), p. 6.

- ^ Dziennik Polski, rok XXX, nr 175 (9456), p. 2.

- ^ Dziennik Polski, rok XX, nr 171 (6363), p. 6.

- ^ "Penderecki historycznie: od narodzin świata do World Trade Center". culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Biography on Krakow 2000". Biurofestiwalowe.pl. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "Krzysztof Penderecki, "II Symfonia" i Joanna Bruzdowicz, "Koncerty" (Olympia)". culture.pl. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Krzysztof Penderecki- Bio, Albums, Pictures – Naxos Classical Music". Naxos.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ Hume, Paul (1 December 1978). "'Paradise Lost,' Krzysztof Penderecki's Long-Awaited Opera 'Paradise Lost': The World PremiereMusic of Vivid Imagination Marks Krzysztof Penderecki's Long-Awaited Opera". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Rilling, Helmuth (2003). "29. mai 2003 • 70. geburtstag". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ Ouverture 2008 Archived 10 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Rheingau Musik Festival, p. 17, 11 July 2008.

- ^ "Penderecki sagt 'Phaedra' für Wien ab". Pizzicato (in German). Luxembourg. 9 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "A composer for all seasons". The Irish Times. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Krzysztof Penderecki engaged in creation of choral work on Armenian Genocide centennial". Armenpress.am. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Famous Polish composer marks Polish centenary in Kiev". polandin.com. 30 September 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Notes on Penderecki". Retrieved 30 August 2016. "Aiming for the Unreachable". Dw.com. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Mazes, Notes & Dali: The Extraordinary Life of Krzysztof Penderecki". Culture.pl.

- ^ "'Here I write different music…' Remembering Penderecki, through his garden…". Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ "Penderecki's Garden". Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^

- "Nie żyje Krzysztof Penderecki – Kultura – Radio Kraków". radiokrakow.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Nie żyje Krzysztof Penderecki. Wybitny polski kompozytor i dyrygent miał 86 lat" (in Polish). gazeta.pl. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Lewis, Daniel (29 March 2020). "Krzysztof Penderecki, Polish Composer With Cinematic Flair, Dies at 86". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Potter, Keith (29 March 2020). "Krzysztof Penderecki obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Scislowska, Monika (30 March 2020). "Polish conductor's music featured in film, concerts around world". The Idaho Statesman. Boise, ID. AP. p. A7. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Krzysztof Penderecki spoczął w Panteonie Narodowym" (in Polish). Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Marian Konieczny". Desa.pl. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Aleja Sław". Um.kielce.pl. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Phil Alexander (29 March 2020). "Krzysztof Penderecki, Atonal Composer Who Influenced Some Of Rock's Heaviest Artists, Dead at 86". kerrang.com. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Service, Tom (23 February 2012). "When Poles collide: Jonny Greenwood's collaboration with Krzysztof Penderecki". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Weird Fruit: Jonny Greenwoods Creative Contribution to 'The Bends'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Krzysztof Penderecki". IMDb. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Liner notes for The Exorcist: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Warner Bros. 16177-00-CD, 1998.

- ^ Barham, J.M. (2009). "Incorporating Monsters: Music as Context, Character and Construction in Kubrick's The Shining" (PDF). Terror Tracks: Music and Sound in Horror Cinema. London, UK: Equinox Press. pp. 137–170. ISBN 978-1-84553-202-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Krzysztof Penderecki (Chronology and Profile)". Schott Music. 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Hiemenz, Jack (27 February 1977). "A Composer Praises God as One Who Lives in Darkness". The New York Times. Vol. 126, no. 43499.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Prizes and Awards". Krzysztofpenderecki.eu. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Trustee Grammy Award". www.grammy.com. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Krzysztof Penderecki". Culture.pl. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Wihuri Sibelius Prize". Wihuriprizes.fi. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Krzysztof Penderecki". usc.edu. Polish Music Center, University of Southern California. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ a b c "Krzysztof Penderecki". Grammy.com. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Music Composition". Grawemeyer.org. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Szalsza, Piotr. "Penderecki, Krzysztof". Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online (in German). Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage, Abteilung Musikwissenschaft. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "PRINCE OF ASTURIAS AWARD FOR THE ARTS 2001". Fpa.es. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Guardini-Preis für Krzysztof Penderecki". Wiener Zeitung (in German). Vienna. 5 July 2002. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 1584. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ "M.P. 2006 nr 2 poz. 20". Prawo.sejm.gov.pl. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Warszawa. Wręczono złote medale "Gloria Artis"". Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Ar Triju Zvaigžņu ordeni apbalvoto personu reģistrs apbalvošanas secībā, sākot no 2004. gada 1.oktobra". Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Odznaczenie Komandora Orderu Lwa Finlandii dla Krzysztofa Pendereckiego". Mkidn.gov.pl. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Miejskie nagrody i wyróżnienia". Torun.pl. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Distinction honorifique pour le compositeur polonais Krzysztof Penderecki". varsovie.mae.lu (in French). Luxembourg: Embassy of Luxembourg in Poland. 19 September 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Oppermann, Andreas (29 March 2020). "Viadrina-Preisträger Krzystof Penderecki gestorben". rbb24.de (in German). Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Penderecki odebrał Nagrodę Viadriny". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "PASZPORTY 2012: kto laureatem?". Polityka.pl. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Teenetemärkide kavalerid". President.ee. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Medal Per Artem ad Deum dla Krzysztofa Pendereckiego, Wincetego Kućmy i wydawnictwa Herder". Perartemaddeum.com. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Nagrody Forum Ekonomicznego". Forum-ekonomiczne.pl. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ "Doktoraty honoris causa". Archive.md. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Odszedł Krzysztof Penderecki, honorowy obywatel Bydgoszczy". bydgoszcz.pl. Bydgoszcz. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Sources

edit- Schwinger, Wolfram (1989). Krzysztof Penderecki: His Life and Work – encounters, biography and musical commentary. Translated by Mann, William. London, England: Schott. ISBN 978-0-946535-11-8.

Further reading

edit- Bylander, Cindy (2004). Krzysztof Penderecki: a bio-bibliography. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313256-58-5. OCLC 56104435.

- Croan, Robert (7 October 1988). "Composer is deft as conductor". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. p. 43. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Croan, Robert (7 October 1988). "Penderecki makes his Pittsburgh debut". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. p. 43. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Diehl, Jackson (10 July 1988). "Penderecki doesn't let Marxism limit style". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. pp. 73, 74. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com. continued on page 74

- Guerrieri, Matthew (29 October 2013). "An unending path". The Boston Globe. Boston. p. G6, G7. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com. continued on page G7

- Hinson, Mark (8 October 2004). "The master conducts his masterwork". Tallahassee Democrat. Tallahassee, Florida. p. 50. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Johnson, Christopher (7 April 1985). "Krzysztof Penderecki is a composer caught in crossfire of critics". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. p. 73. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Maciejewski, B. M. (1976). Twelve Polish Composers. London, England: Allegro Press. ISBN 978-0-950561-90-5. OCLC 3650196.

- Miller, Margo (19 January 1986). "Penderecki to conduct Requiem". The Boston Globe. Boston. p. 121. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Robinson, Ray (1983). Krzysztof Penderecki: a guide to his works. Princeton, New Jersey: Prestige Publications. ISBN 978-0-911009-02-6. OCLC 9541916.

- Rosenberg, Donald (24 November 1983). "Polish composer's music elicits strong reaction". The Akron Beacon Journal. Akron, Ohio. p. 75. Retrieved 25 May 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Thomas, Adrian (1992). "Penderecki, Krzysztof". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). New Grove Dictionary of Opera. London, England. ISBN 978-0-333-73432-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thomas, Adrian (2008). Polish Music since Szymanowski. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-44118-6.

- "Rede: Trauerstaatsakt für Krzysztof Penderecki". Der Bundespräsident (in German). 22 March 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

External links

edit- "Penderecki's violin revolution in Poland" Archived 9 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Drowned In Sound, 2012)

- Krzysztof Penderecki interview by Bruce Duffie (March 2000)

- Interview with Krzysztof Penderecki by Galina Zhukova (2011), Журнал reMusik, Saint-Petersburg Contemporary Music Center.

- "Krzysztof Penderecki: Turning history into avant-garde". Video interview by Louisiana Channel, Denmark, 2013.

- "Krzysztof Penderecki (biography, works, resources)" (in French and English). IRCAM.

- Krzysztof Penderecki, Culture.pl

- Krzysztof Penderecki's biography on Cdmc website

- Krzysztof Penderecki at IMDb

- Krzysztof Penderecki discography at Discogs

- Not Just 'The Shining': 13 Soundtracks Featuring Krzysztof Penderecki on Culture.pl

- Musical Trace Pendereckis' film & theatre music (Polish only)

- Penderecki's Garden, digital garden from the Adam Mickiewicz Institute launched on 29 March 2021 for the anniversary of his death.