The Koinmerburra people, also known as Koinjmal, Guwinmal, Kungmal and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the state of Queensland. They are the traditional owners of an area which includes part of the Great Barrier Reef.

Country

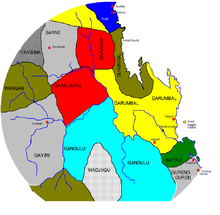

editKoinmerburra traditional lands covered an estimated 4,100 square kilometres (1,600 sq mi), taking in the western slopes of Pine Mountain in the Normanby Range to the Styx River. They occupied the coastal strip from Broad Sound northwards to Cape Palmerston and took in St. Lawrence. Their inland extensions went as far as the Coast Range, and, to the south, ended around Marlborough. Ecologically, they worked large areas of mangrove mudflats, and employed bark canoes to navigate these shoreline zones.[1]

Social organisation

editThe Koinmerburra consisted of several kin groups, the name of at least one of which is known:

According to an early Rockhampton informant, W. H. Flowers, responding to a request for information by Alfred William Howitt, the Koinjmal were divided into two moieties, the Yungeru and the Witteru, each in turn subdivided into two sections, creating 4 sub-classes:[3]

The Yungeru were split into the Kurpal (Eaglkehawk totem) and the Kuialla (Laughing jackass totem): the Witteru divided into the Karilbura and Munaal, which had several totems, including the wallaby, Curlew, Hawk, Clearwater and Sand.[4]

Marriage

editAccording to Flowers, marriages were contracted early, in infancy, when a girl's parents would arrange her marriage to an elder man, who, after the ceremony of betrothal would supply her regularly with game and fish, while scrupulously avoiding going near the camp of her parents or speaking to the mother.[5]

The ceremony was finalised in the following manner:

The parents having painted the girl and dressed her hair with feathers, her male cousin[a] takes her to where her future husband is sitting cross-legged in silence, and seats her at his back, and close to him. He who has brought the girl after a time removes the feathers from her hair and places them in the hair of her future husband, and then leads the girl back to her parents.[5]

The actual marriage was sealed by a simulated kidnapping of the young girl.

when a girl who has been promised is considered to be old enough for marriage by her father, he sends the girl as usual with the other women to gather yams or other food, and he tells the man to whom he has promised her, who, then painting himself, takes his weapons and follows her, inviting all the unmarried men in the camp to assist him. When they come up with the women he goes forward alone, and telling the girl he has come for her he takes her by the wrist or hand. The women at once surround her and try to keep her from him. She tries to escape, and if she does not like him she bites his wrist, this being an understood sign that she refuses him.[7]

History

editSome Koinmerburra kin groups could be found living beyond their traditional lands, at places like Yaamba and Bombandy, at the beginning of the 20th century, but this displacement was the consequence of white encroachments, which drove them to push south of their homeland.[1]

Language

editAlternative names

editAs of 2020, the usual name used for this people is Koinmerburra.[9][10]

Some words

edit- kuinmur (a plain)

Natural resource management

editThe Traditional Owner Reference Group consisting of representatives of the Yuwibara, Koinmerburra, Barada Barna, wiri, Ngaro, and those Gia and Juru people whose lands are within Reef Catchments Mackay Whitsunday Isaac region, helps to support natural resource management and look after the cultural heritage sites in the area.[10]

Notes

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d Tindale 1974, p. 176.

- ^ Tindale 1974, p. 167.

- ^ Howitt 1884, p. 336.

- ^ Howitt 1884, p. 335.

- ^ a b Howitt 1889, p. 118.

- ^ Howitt 1889, p. 118, note.

- ^ Howitt 1889, p. 123.

- ^ a b E49 Guwinbal at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ^ Lyons, Ilisapeci; Hill, Rosemary; Deshong, Samarla; Mooney, Gary; Turpin, Gerry (2020). "Protecting what is left after colonisation: embedding climate adaptation planning in traditional owner narratives". Geographical Research. 58 (1). Wiley: 34–48. Bibcode:2020GeoRs..58...34L. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12385. ISSN 1745-5863. S2CID 213375090.

- ^ a b "Traditional Owners". Reef Catchments. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

References

edit- Dixon, Robert M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.

- Howitt, A. W. (1884). Palmer, Edward (ed.). "Notes on Some Australian Tribes". Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 13: 335–347. doi:10.2307/2841896. JSTOR 2841896.

- Howitt, Alfred William (1889). "On the organisation of Australian tribes". Transactions of the Royal Society of Victoria. 1 (2): 96–137.

- Howitt, Alfred William (1904). The native tribes of south-east Australia (PDF). Macmillan.

- Moore, Clive (1990). "Blackgin's Leap: A Window into Aboriginal-European Relations in the Pioneer Valley, Queensland in the 1860s" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 14 (1): 61–79.

- Muller, Frederic (1887). "Broad Sound, Yaamba, Maryborough, and St. Lawrence" (PDF). In Curr, Edward Micklethwaite (ed.). The Australian race: its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia and the routes by which it spread itself over the continent. Vol. 3. Melbourne: J. Ferres. pp. 52–53.

- Smyth, Robert Brough (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria: with notes relating to the habits of the natives of other parts of Australia and Tasmania (PDF). Vol. 1. Melbourne: J. Ferres, gov't printer.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Koinjmal (QLD)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press.