The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from the High Middle Ages to 1848 during its dissolution. It was also an early colonial power, with colonies in Asia and Africa, and the largest being New France in North America centred around the Great Lakes.

Kingdom of France Reaume de France (Old French) Royaulme de France (Middle French) Royaume de France (French) Regnum Franciæ (Latin) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 843–1792 1814–1815 1815–1848 | |||||||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||||||

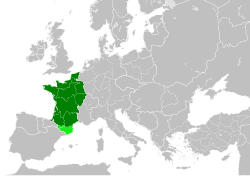

The Kingdom of France in 1000 | |||||||||||||

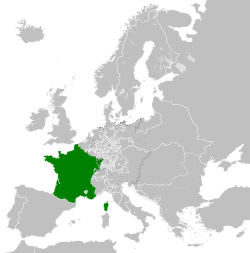

The Kingdom of France in 1789 | |||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||

| Largest city | Paris | ||||||||||||

| Official languages | Latin (until 1539) • French (from the 12th century) | ||||||||||||

| Regional languages | Breton, Franco-Provençal, Occitan, Norman, Picard, Champenois, Angevin, Gallo, Burgundian, Poitevin, Basque, Alsatian | ||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | French | ||||||||||||

| Government |

| ||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||

• 843–877 (first) | Charles the Bald | ||||||||||||

• 1830–1848 (last) | Louis Philippe I | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1815 | Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand | ||||||||||||

• 1847–1848 | François Guizot | ||||||||||||

| Legislature |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval/Early modern | ||||||||||||

| c. 10 August 843 | |||||||||||||

• Capetian dynasty established | 3 July 987 | ||||||||||||

| 1337–1453 | |||||||||||||

| 1562–1598 | |||||||||||||

| 5 May 1789 | |||||||||||||

| 21 September 1792 | |||||||||||||

| 6 April 1814 | |||||||||||||

| 2 August 1830 | |||||||||||||

| 24 February 1848 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Livre, Livre parisis, Livre tournois, Denier, Sol/Sou, Franc, Écu, Louis d'or | ||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | FR | ||||||||||||

Map of the first (light blue) and second (dark blue) French colonial empires. | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Kingdom of France was descended directly from the western Frankish realm of the Carolingian Empire, which was ceded to Charles the Bald with the Treaty of Verdun (843). A branch of the Carolingian dynasty continued to rule until 987, when Hugh Capet was elected king and founded the Capetian dynasty. The territory remained known as Francia and its ruler as rex Francorum ('king of the Franks') well into the High Middle Ages. The first king calling himself rex Francie ('King of France') was Philip II, in 1190, and officially from 1204. From then, France was continuously ruled by the Capetians and their cadet lines under the Valois and Bourbon until the monarchy was abolished in 1792 during the French Revolution. The Kingdom of France was also ruled in personal union with the Kingdom of Navarre over two time periods, 1284–1328 and 1572–1620, after which the institutions of Navarre were abolished and it was fully annexed by France (though the King of France continued to use the title "King of Navarre" through the end of the monarchy).

France in the Middle Ages was a decentralised, feudal monarchy. In Brittany and Catalonia (the latter now a part of Spain), as well as Aquitaine, the authority of the French king was barely felt. Lorraine, Provence and East Burgundy were states of the Holy Roman Empire and not yet a part of France. West Frankish kings were initially elected by the secular and ecclesiastical magnates, but the regular coronation of the eldest son of the reigning king during his father's lifetime established the principle of male primogeniture, which became codified in the Salic law. During the Late Middle Ages, rivalry between the Capetian dynasty, rulers of the Kingdom of France and their vassals the House of Plantagenet, who also ruled the Kingdom of England as part of their so-called competing Angevin Empire, resulted in many armed struggles. The most notorious of them all are the series of conflicts known as the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) in which the kings of England laid claim to the French throne. Emerging victorious from said conflicts, France subsequently sought to extend its influence into Italy, but after initial gains was defeated by Spain and the Holy Roman Empire in the ensuing Italian Wars (1494–1559).

France in the early modern era was increasingly centralised; the French language began to displace other languages from official use, and the monarch expanded his absolute power in an administrative system, known as the Ancien Régime, complicated by historic and regional irregularities in taxation, legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions, and local prerogatives. Religiously, France became divided between the Catholic majority and a Protestant minority, the Huguenots, which led to a series of civil wars, the Wars of Religion (1562–1598). The Wars of Religion crippled France, but triumph over Spain and the Habsburg monarchy in the Thirty Years' War made France the most powerful nation on the continent once more. The kingdom became Europe's dominant cultural, political and military power in the 17th century under Louis XIV. Throughout the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries, France was Europe's richest, largest, most populous, powerful and influential country.[2] In parallel, France developed its first colonial empire in Asia, Africa, and in the Americas.

In the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over 10,000,000 square kilometres (3,900,000 sq mi), the second-largest empire in the world at the time behind the Spanish Empire. Colonial conflicts with Great Britain led to the loss of much of its North American holdings by 1763. French intervention in the American Revolutionary War helped the United States secure independence from King George III and the Kingdom of Great Britain, but was costly and achieved little for France.

France through its French colonial empire, became a superpower from 1643 until 1815;[3][4] from the reign of King Louis XIV until the defeat of Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars.[5] The Spanish Empire lost its superpower status to France after the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees (but maintained the status of Great Power until the Napoleonic Wars and the Independence of Spanish America). France lost its superpower status after Napoleon's defeat against the British, Prussians and Russians in 1815.[6]

Following the French Revolution, which began in 1789, the Kingdom of France adopted a written constitution in 1791, but the Kingdom was abolished a year later and replaced with the First French Republic. The monarchy was restored by the other great powers in 1814 and, with the exception of the Hundred Days in 1815, lasted until the French Revolution of 1848.

Political history

editWest Francia

editDuring the later years of Charlemagne's rule, the Vikings made advances along the northern and western perimeters of the Kingdom of the Franks. After Charlemagne's death in 814 his heirs were incapable of maintaining political unity and the empire began to crumble. The Treaty of Verdun of 843 divided the Carolingian Empire into three parts, with Charles the Bald ruling over West Francia, the nucleus of what would develop into the kingdom of France.[7] Charles the Bald was also crowned King of Lotharingia after the death of Lothair II in 869, but in the Treaty of Meerssen (870) was forced to cede much of Lotharingia to his brothers, retaining the Rhône and Meuse basins (including Verdun, Vienne and Besançon) but leaving the Rhineland with Aachen, Metz, and Trier in East Francia.

Viking incursions up the Loire, the Seine, and other inland waterways increased. During the reign of Charles the Simple (898–922), Vikings under Rollo from Scandinavia settled along the Seine, downstream from Paris, in a region that came to be known as Normandy.[8]

High Middle Ages

editThe Carolingians were to share the fate of their predecessors: after an intermittent power struggle between the two dynasties, the accession in 987 of Hugh Capet, Duke of France and Count of Paris, established the Capetian dynasty on the throne. With its offshoots, the houses of Valois and Bourbon, it was to rule France for more than 800 years.[9]

The old order left the new dynasty in immediate control of little beyond the middle Seine and adjacent territories, while powerful territorial lords such as the 10th- and 11th-century counts of Blois accumulated large domains of their own through marriage and through private arrangements with lesser nobles for protection and support.

The area around the lower Seine became a source of particular concern when Duke William of Normandy took possession of the Kingdom of England by the Norman Conquest of 1066, making himself and his heirs the king's equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown).

Henry II inherited the Duchy of Normandy and the County of Anjou, and married France's newly single ex-queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who ruled much of southwest France, in 1152. After defeating a revolt led by Eleanor and three of their four sons, Henry had Eleanor imprisoned, made the Duke of Brittany his vassal, and in effect ruled the western half of France as a greater power than the French throne. However, disputes among Henry's descendants over the division of his French territories, coupled with John of England's lengthy quarrel with Philip II, allowed Philip to recover influence over most of this territory. After the French victory at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, the English monarchs maintained power only in southwestern Duchy of Aquitaine.[10]

Late Middle Ages and the Hundred Years' War

editThe death of Charles IV of France in 1328 without male heirs ended the main Capetian line. Under Salic law the crown could not pass through a woman (Philip IV's daughter was Isabella, whose son was Edward III of England), so the throne passed to Philip VI, son of Charles of Valois. This, in addition to a long-standing dispute over the rights to Gascony in the south of France, and the relationship between England and the Flemish cloth towns, led to the Hundred Years' War of 1337–1453. The following century was to see devastating warfare, the Armagnac–Burgundian Civil War, peasant revolts (the English peasants' revolt of 1381 and the Jacquerie of 1358 in France) and the growth of nationalism in both countries.[11]

The losses of the century of war were enormous, particularly owing to the plague (the Black Death, usually considered an outbreak of bubonic plague), which arrived from Italy in 1348, spreading rapidly up the Rhône valley and thence across most of the country: it is estimated that a population of some 18–20 million in modern-day France at the time of the 1328 hearth tax returns had been reduced 150 years later by 50 percent or more.[12]

Renaissance and Reformation

editThe Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture (much of it imported from Italy).[13] The kings built a strong fiscal system, which heightened the power of the king to raise armies that overawed the local nobility.[14] In Paris especially there emerged strong traditions in literature, art and music. The prevailing style was classical.[15]

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts was signed into law by Francis I in 1539. Largely the work of Chancellor Guillaume Poyet, it dealt with a number of government, judicial and ecclesiastical matters. Articles 110 and 111, the most famous, called for the use of the French language in all legal acts, notarised contracts and official legislation.

Italian Wars

editAfter the Hundred Years' War, Charles VIII of France signed three additional treaties with Henry VII of England, Emperor Maximilian I, and Ferdinand II of Aragon respectively at Étaples (1492), Senlis (1493) and Barcelona (1493). These three treaties cleared the way for France to undertake the long Italian Wars (1494–1559), which marked the beginning of early modern France. French efforts to gain dominance resulted only in the increased power of the House of Habsburg.

Wars of Religion

editBarely were the Italian Wars over, when France was plunged into a domestic crisis with far-reaching consequences. Despite the conclusion of a Concordat between France and the Papacy (1516), granting the crown unrivalled power in senior ecclesiastical appointments, France was deeply affected by the Protestant Reformation's attempt to break the hegemony of Catholic Europe. A growing urban-based Protestant minority (later dubbed Huguenots) faced ever harsher repression under the rule of Francis I's son King Henry II. After Henry II's death in a joust, the country was ruled by his widow Catherine de' Medici and her sons Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. Renewed Catholic reaction headed by the powerful dukes of Guise culminated in a massacre of Huguenots (1572), starting the first of the French Wars of Religion, during which English, German, and Spanish forces intervened on the side of rival Protestant and Catholic forces. Opposed to absolute monarchy, the Huguenot Monarchomachs theorized during this time the right of rebellion and the legitimacy of tyrannicide.[16]

The Wars of Religion culminated in the War of the Three Henrys in which Henry III assassinated Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic League, and the king was murdered in return. After the assassination of both Henry of Guise (1588) and Henry III (1589), the conflict was ended by the accession of the Protestant king of Navarre as Henry IV (first king of the Bourbon dynasty) and his subsequent abandonment of Protestantism (Expedient of 1592) effective in 1593, his acceptance by most of the Catholic establishment (1594) and by the Pope (1595), and his issue of the toleration decree known as the Edict of Nantes (1598), which guaranteed freedom of private worship and civil equality.[17]

Early modern period

editColonial France

editFrance's pacification under Henry IV laid much of the ground for the beginnings of France's rise to European hegemony. France was expansive during all but the end of the seventeenth century: the French began trading in India and Madagascar, founded Quebec and penetrated the North American Great Lakes and Mississippi, established plantation economies in the West Indies and extended their trade contacts in the Levant and enlarged their merchant marine.

Thirty Years' War

editHenry IV's son Louis XIII and his minister (1624–1642) Cardinal Richelieu, elaborated a policy against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) which had broken out in Germany. After the death of both king and cardinal, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) secured universal acceptance of Germany's political and religious fragmentation, but the Regency of Anne of Austria and her minister Cardinal Mazarin experienced a civil uprising known as the Fronde (1648–1653) which expanded into a Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659). The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) formalised France's seizure (1642) of the Spanish territory of Roussillon after the crushing of the ephemeral Catalan Republic and ushered a short period of peace.[18]

Administrative structures

editThe Ancien Régime, a French term rendered in English as "Old Rule", or simply "Former Regime", refers primarily to the aristocratic, social and political system of early modern France under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The administrative and social structures of the Ancien Régime were the result of years of state-building, legislative acts (like the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts), internal conflicts and civil wars, but they remained a confusing patchwork of local privilege and historic differences until the French Revolution brought about a radical suppression of administrative incoherence.

Louis XIV, the Sun King

editFor most of the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715), ("The Sun King"), France was the dominant power in Europe, aided by the diplomacy of Cardinal Richelieu's successor as the King's chief minister, (1642–61) Cardinal Jules Mazarin, (1602–1661). Cardinal Mazarin oversaw the creation of a French Royal Navy that rivalled England's, expanding it from 25 ships to almost 200. The size of the French Royal Army was also considerably increased. Renewed wars (the War of Devolution, 1667–1668 and the Franco-Dutch War, 1672–1678) brought further territorial gains (Artois and western Flanders and the free County of Burgundy, previously left to the Empire in 1482), but at the cost of the increasingly concerted opposition of rival royal powers, and a legacy of an increasingly enormous national debt. An adherent of the theory of the "Divine Right of Kings", which advocates the divine origin of temporal power and any lack of earthly restraint of monarchical rule, Louis XIV continued his predecessors' work of creating a centralized state governed from the capital of Paris. He sought to eliminate the remnants of feudalism still persisting in parts of France and, by compelling the noble elite to regularly inhabit his lavish Palace of Versailles, built on the outskirts of Paris, succeeded in pacifying the aristocracy, many members of which had participated in the earlier "Fronde" rebellion during Louis' minority. By these means he consolidated a system of absolute monarchy in France that endured 150 years until the French Revolution.[19] McCabe says critics used fiction to portray the degraded Turkish court, using "the harem, the Sultan court, oriental despotism, luxury, gems and spices, carpets, and silk cushions" as an unfavorable analogy to the corruption of the French royal court.[20]

The king sought to impose total religious uniformity on the country, repealing the Edict of Nantes in 1685. It is estimated that anywhere between 150,000 and 300,000 Protestants fled France during the wave of persecution that followed the repeal,[21] (following "Huguenots" beginning a hundred and fifty years earlier until the end of the 18th century) costing the country a great many intellectuals, artisans, and other valuable people. Persecution extended to unorthodox Roman Catholics like the Jansenists, a group that denied free will and had already been condemned by the popes. In this, he garnered the friendship of the papacy, which had previously been hostile to France because of its policy of putting all church property in the country under the jurisdiction of the state rather than that of Rome.[22]

In November 1700, King Charles II of Spain died, ending the Habsburg line in that country. Louis had long planned for this moment, but these plans were thrown into disarray by the will of King Charles, which left the entire Spanish Empire to Louis's grandson Philip, Duke of Anjou, (1683–1746). Essentially, Spain was to become a perpetual ally and even obedient satellite of France, ruled by a king who would carry out orders from Versailles. Realizing how this would upset the balance of power, the other European rulers were outraged. However, most of the alternatives were equally undesirable. For example, putting another Habsburg on the throne would end up recreating the grand multi-national Empire of Charles V; of the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and the Spanish territories in Italy, which would also grossly upset the power balance. However, the rest of Europe would not stand for his ambitions in Spain, and so the long War of the Spanish Succession began (1701–1714), a mere three years after the War of the Grand Alliance (1688–1697, a.k.a. "War of the League of Augsburg") had just concluded.[23]

Dissent and revolution

editThe reign (1715–1774) of Louis XV saw an initial return to peace and prosperity under the regency (1715–1723) of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, whose policies were largely continued (1726–1743) by Cardinal Fleury, prime minister in all but name. The exhaustion of Europe after two major wars resulted in a long period of peace, only interrupted by minor conflicts like the War of the Polish Succession from 1733 to 1735. Large-scale warfare resumed with the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). But alliance with the traditional Habsburg enemy (the "Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756) against the rising power of Britain and Prussia led to costly failure in the Seven Years' War (1756–63) and the loss of France's North American colonies.[24]

On the whole, the 18th century saw growing discontent with the monarchy and the established order. Louis XV was a highly unpopular king for his sexual excesses, overall weakness, and for losing New France to the British. The writings of the philosophes such as Voltaire were a clear sign of discontent, but the king chose to ignore them. He died of smallpox in 1774, and the French people shed few tears at his death. While France had not yet experienced the Industrial Revolution that was beginning in Britain, the rising middle class of the cities felt increasingly frustrated with a system and rulers that seemed silly, frivolous, aloof, and antiquated, even if true feudalism no longer existed in France.

Upon Louis XV's death, his grandson Louis XVI became king. Initially popular, he too came to be widely detested by the 1780s. He was married to an Austrian archduchess, Marie Antoinette. French intervention in the American War of Independence was also very expensive.[25]

With the country deeply in debt, Louis XVI permitted the radical reforms of Turgot and Malesherbes, but noble disaffection led to Turgot's dismissal and Malesherbes' resignation in 1776. They were replaced by Jacques Necker. Necker had resigned in 1781 to be replaced by Calonne and Brienne, before being restored in 1788. A harsh winter that year led to widespread food shortages, and by then France was a powder keg ready to explode.[26] On the eve of the French Revolution of July 1789, France was in a profound institutional and financial crisis, but the ideas of the Enlightenment had begun to permeate the educated classes of society.[23]

Limited monarchy

editOn September 3, 1791, the absolute monarchy which had governed France for 948 years was forced to limit its power and become a provisional constitutional monarchy. However, this too would not last very long and on September 21, 1792, the French monarchy was effectively abolished by the proclamation of the French First Republic. The role of the King in France was finally ended with the execution of Louis XVI by guillotine on Monday, January 21, 1793, followed by the "Reign of Terror", mass executions and the provisional "Directory" form of republican government, and the eventual beginnings of twenty-five years of reform, upheaval, dictatorship, wars and renewal, with the various Napoleonic Wars.

Restoration

editFollowing the French Revolution (1789–99) and the First French Empire under Napoleon (1804–1814), the monarchy was restored when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the House of Bourbon in 1814. However the deposed Emperor Napoleon I returned triumphantly to Paris from his exile in Elba and ruled France for a short period known as the Hundred Days.

When a Seventh European Coalition again deposed Napoleon after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the Bourbon monarchy was once again restored. The Count of Provence - brother of Louis XVI, who was guillotined in 1793 - was crowned as Louis XVIII, nicknamed "The Desired". Louis XVIII tried to conciliate the legacies of the Revolution and the Ancien Régime, by permitting the formation of a Parliament and a constitutional Charter, usually known as the "Charte octroyée" ("Granted Charter"). His reign was characterized by disagreements between the Doctrinaires, liberal thinkers who supported the Charter and the rising bourgeoisie, and the Ultra-royalists, aristocrats and clergymen who totally refused the Revolution's heritage. Peace was maintained by statesmen like Talleyrand and the Duke of Richelieu, as well as the King's moderation and prudent intervention.[27] In 1823, the Trienio Liberal revolt in Spain led to a French intervention on the royalists' side, which permitted King Ferdinand VII of Spain to abolish the Constitution of 1812.

However, the work of Louis XVIII was frustrated when, after his death on 16 September 1824, his brother the Count of Artois became king under the name of Charles X. Charles X was a strong reactionary who supported the ultra-royalists and the Catholic Church. Under his reign, the censorship of newspapers was reinforced, the Anti-Sacrilege Act passed, and compensations to Émigrés were increased. However, the reign also witnessed the French intervention in the Greek Revolution in favour of the Greek rebels, and the first phase of the conquest of Algeria.

The absolutist tendencies of the King were disliked by the Doctrinaire majority in the Chamber of Deputies, that on 18 March 1830 sent an address to the King, upholding the rights of the Chamber and in effect supporting a transition to a full parliamentary system. Charles X received this address as a veiled threat, and in 25 July of the same year, he issued the St. Cloud Ordinances, in an attempt to reduce Parliament's powers and re-establish absolute rule.[28] The opposition reacted with riots in Parliament and barricades in Paris, that resulted in the July Revolution.[29] The King abdicated, as did his son the Dauphin Louis Antoine, in favour of his grandson Henri, Count of Chambord, nominating his cousin the Duke of Orléans as regent.[30] However, it was too late, and the liberal opposition won out over the monarchy.

Aftermath and July Monarchy

editOn 9 August 1830, the Chamber of Deputies elected Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans as "King of the French": for the first time since French Revolution, the King was designated as the ruler of the French people and not the country. The Bourbon white flag was substituted with the French tricolour,[31] and a new Charter was introduced in August 1830.[32]

The conquest of Algeria continued, and new settlements were established in the Gulf of Guinea, Gabon, Madagascar, and Mayotte, while Tahiti was placed under protectorate.[33]

However, despite the initial reforms, Louis Philippe was little different from his predecessors. The old nobility was replaced by urban bourgeoisie, and the working class was excluded from voting.[34] Louis Philippe appointed notable bourgeois as Prime Minister, like banker Casimir Périer, academic François Guizot, general Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and thus obtained the nickname of "Citizen King" (Roi-Citoyen). The July Monarchy was beset by corruption scandals and financial crisis. The opposition of the King was composed of Legitimists, supporting the Count of Chambord, Bourbon claimant to the throne, and of Bonapartists and Republicans, who fought against royalty and supported the principles of democracy.

The King tried to suppress the opposition with censorship, but when the Campagne des banquets ("Banquets' Campaign") was repressed in February 1848,[35] riots and seditions erupted in Paris and later all France, resulting in the February Revolution. The National Guard refused to repress the rebellion, resulting in Louis Philippe abdicating and fleeing to England. On 24 February 1848, the monarchy was abolished and the Second Republic was proclaimed.[36] Despite later attempts to re-establish the Kingdom in the 1870s, during the Third Republic, the French monarchy has not restored.

Territories and provinces

editBefore the 13th century, only a small part of what is now France was under control of the Frankish king; in the north there were Viking incursions leading to the formation of the Duchy of Normandy; in the west, the counts of Anjou established themselves as powerful rivals of the king, by the late 11th century ruling over the "Angevin Empire", which included the kingdom of England. It was only with Philip II of France that the bulk of the territory of Western Francia came under the rule of the Frankish kings, and Philip was consequently the first king to call himself "king of France" (1190). The division of France between the Angevin (Plantagenet) kings of England and the Capetian kings of France would lead to the Hundred Years' War, and France would regain control over these territories only by the mid 15th century. What is now eastern France (Lorraine, Arelat) was not part of Western Francia to begin with and was only incorporated into the kingdom during the early modern period.

Territories inherited from Western Francia:

- Domain of the Frankish king (royal domain or demesne, see crown lands of France)

- Direct vassals of the French king in the 10th to 12th centuries:

- County of Champagne (to the royal domain in 1316)

- County of Blois (to the royal domain in 1391)

- Duchy of Burgundy (until 1477, then divided between France and the Habsburgs)

- County of Flanders (to Burgundy in 1369)

- Duchy of Bourbon (1327–1523)

Acquisitions during the 13th to 14th centuries:

- Duchy of Normandy (1204)

- County of Tourain (1204)

- County of Anjou (1225)

- County of Maine (1225)

- County of Auvergne (1271)

- County of Toulouse (1271), including:

- County of Quercy

- County of Rouergue

- County of Gevaudan

- Viscounty of Albi

- Marquisat of Gothia

- County of Champagne (to the royal domain in 1316)

- Dauphiné (1349), hereditary possession of the kings of France, to be held by the heir apparent, but technically not part of the kingdom of France because it remained nominally part of the Holy Roman Empire.

- County of Blois (to the royal domain in 1391)

Acquisitions from the Plantagenet kings of England with the French victory in the Hundred Years' War 1453

- Duchy of Aquitaine (Guyenne), including:

- County of Poitou

- County of La Marche

- County of Angoulême

- County of Périgord

- County of Velay

- County of Saintonge

- Viscounty of Limousin

- Lordship of Issoudun

- Lordship of Déols

- Duchy of Gascogne (Gascony)

- County of Agenais

- Duchy of Bretagne (disputed since the War of the Breton Succession, to France in 1453, to the royal demesne in 1547)

Acquisitions after the end of the Hundred Years' War:

- Duchy of Burgundy (1477)

- Pale of Calais (1558)

- Kingdom of Navarre (1620)

- Alsace: Peace of Westphalia (1648), Treaty of Nijmegen, Truce of Ratisbon (1684)

- County of Artois (1659)

- Roussillon and Perpignan, Montmédy and other parts of Luxembourg, parts of Flanders, including Arras, Béthune, Gravelines and Thionville (Treaty of the Pyrenees 1659)

- Free County of Burgundy (1668, 1679)

- French Hainaut (1679)

- Principality of Orange (1713)

- Duchy of Lorraine (1766)

- French conquest of Corsica (1769)

- Comtat Venaissin (1791)

Religion

editPrior to the French Revolution, the Catholic Church was the official state religion of the Kingdom of France.[37] France was traditionally considered the Church's eldest daughter (French: Fille aînée de l'Église), and the King of France always maintained close links to the Pope,[38] receiving the title Most Christian Majesty from the Pope in 1464.[39] However, the French monarchy maintained a significant degree of autonomy, namely through its policy of "Gallicanism", whereby the king selected bishops rather than the papacy.[40]

During the Protestant Reformation of the mid 16th century, France developed a large and influential Protestant population, primarily of Reformed confession; after French theologian and pastor John Calvin introduced the Reformation in France, the number of French Protestants (Huguenots) steadily swelled to 10 percent of the population, or roughly 1.8 million people. The ensuring French Wars of Religion, and particularly the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, decimated the Huguenot community;[41] Protestants declined to seven to eight percent of the kingdom's population by the end of the 16th century. The Edict of Nantes brought decades of respite until its revocation in the late 17th century by Louis XIV. The resulting exodus of Huguenots from the Kingdom of France created a brain drain, as many of them had occupied important places in society.[42]

Jews have a documented presence in France since at least the early Middle Ages.[43] The Kingdom of France was a center of Jewish learning in the Middle Ages, producing influential Jewish scholars such as Rashi and even hosting theological debates between Jews and Christians. Widespread persecution began in the 11th century and increased intermittently throughout the Middle Ages, with multiple expulsions and returns.[44]

Fundamental laws

editSee also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Gallie, Duncan (January 26, 1984). Social Inequality and Class Radicalism in France and Britain. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521257640 – via Google Books.

- ^ R.R. Palmer; Joel Colton (1978). A History of the Modern World (5th ed.). p. 161.

- ^ Aldrich, Robert (1996). Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion. p. 304.

- ^ Page, Melvin E., ed. (2003). Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 218. ISBN 9781576073353 – via Google Books.

- ^ Englund, Steven (2005). Napoleon: A Political Life. Harvard University Press. p. 254.

- ^ Englund, Steven (2005). Napoleon: A Political Life. Harvard University Press. p. 254.

- ^ Price, Roger (2005). A Concise History of France. Cambridge University Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780521844802.

- ^ Bradbury, Jim (2007). The Capetians: Kings of France, 987–1328. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781852855284.; Airlie, Stuart (1993). "Review article: After Empire-recent work on the emergence of post-Carolingian kingdoms". Early Medieval Europe. 2 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.1993.tb00015.x.

- ^ William W. Kibler (1995). Medieval France: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 879. ISBN 9780824044442.

- ^ Peter Shervey Lewis, Later medieval France: the polity (1968).

- ^ Alice Minerva Atkinson, A Brief History of the Hundred Years' War (2012)

- ^ Joseph P. Byrne (2006). Daily life during the Black Death. Greenwood. ISBN 9780313332975.

- ^ James Russell Major, Representative Institutions in Renaissance France, 1421–1559 (1983).

- ^ Martin Wolfe, The fiscal system of renaissance France (1972).

- ^ Yarrow, Philip John (1974). A literary history of France: Renaissance France 1470–1589.; Zerner, Henri (2003). Renaissance art in France: the invention of classicism. Flammarion.

- ^ Holt, Mack P. (2005). The French wars of religion, 1562–1629.

- ^ Buisseret, David (1990). Henry IV: King of France. Routledge. ISBN 9780044456353.

- ^ Peter H. Wilson, Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years' War (2009).

- ^ Beik, William (2000). Louis XIV and Absolutism: A Brief Study with Documents.

- ^ McCabe, Ina Baghdiantz (2008). Orientalism in Early Modern France: Eurasian Trade, Exoticism, and the Ancien Régime. Berg. p. 134. ISBN 9781847884633.

- ^ "La Rome protestante face aux exilés de la foi". Le Temps (in French). 13 July 2010.; Le Refuge protestant urbain au temps de la révocation de l'Édit de Nantes. Histoire (in French). Presses universitaires de Rennes. 5 February 2015. pp. 199–215. ISBN 9782753531307.

- ^ Wolf, John B. (1972). Louis XIV. Springer. ISBN 9781349014705.

- ^ a b Daniel Roche, France in the Enlightenment (1998)

- ^ Colin Jones, The Great Nation: France from Louis XV to Napoleon (2003)

- ^ William Doyle, The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction (2001)

- ^ Sylvia Neely, A Concise History of the French Revolution (2008)

- ^ Actes du congrès – vol. 3, 1961, p. 441.; Emmanuel de Waresquiel, 2003, pp. 460–461.

- ^ Duc de Dolberg, Castellan, II, 176 (letter 30 April 1827)

- ^ Mansel, Philip, Paris Between Empires (St. Martin Press, New York 2001) p. 245.

- ^ Bulletin des lois de la République franc̜aise, Vol. 9. Imprimerie nationale. 1831.

- ^ Michel Pastoureau (2001). Les emblèmes de la France. Bonneton. p. 223.

- ^ Barjot, Dominique; Chaline, Jean-Pierre; Encrevé, André (2014). La France au xixe siècle. Presses Universitaires de France. p. 656.

- ^ Barjot, Chaline & Encrevé (2014), pp. 232, 233.

- ^ Barjot, Chaline & Encrevé (2014), p. 202.

- ^ Barjot, Chaline & Encrevé (2014), pp. 211, 2012.

- ^ Barjot, Chaline & Encrevé (2014), pp. 298, 299.

- ^ Wolf, John Baptiste Wolf (1962). The Emergence of European Civilization: From the Middle Ages to the Opening of the Nineteenth Century. University of Virginia Press. p. 419. ISBN 9789733203162.

- ^ Parisse, Michael (2005). "Lotharingia". In Reuter, T. (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900–c. 1024. Vol. III. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–315.

- ^ "Christian Majesty, His Most".

- ^ Wolfe, M. (2005). Jotham Parsons. The Church in the Republic: Gallicanism and Political Ideology in Renaissance France. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. 2004. pp. ix, 322. The American Historical Review, 110(4), 1254–1255.

- ^ Hans J. Hillerbrand, Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set, paragraphs "France" and "Huguenots"; The Huguenot Population of France, 1600–1685: The Demographic Fate and Customs of a Religious Minority by Philip Benedict; American Philosophical Society, 1991, 164

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed, Frank Puaux, "Huguenot"

- ^ Henri Pirenne (2001). Mahomet et Charlemagne (reprint of 1937 classic) (in French). Dover Publications. pp. 123–128. ISBN 0-486-42011-6.

- ^ Miller, Chaim (2013). "Rashi's Method of Biblical Commentary". chabad.org.

- ^ Dignat 2021.

Works cited

edit- Dignat, Alban (27 May 2021). Grégor, Isabelle (ed.). "XVIIe siècle : Absolutisme et monarchie en France" [17th century: Absolutism and Monarchy in France]. Herodote.net (in French). Herodote.net SAS. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

Further reading

edit- Beik, William. A Social and Cultural History of Early Modern France (2009) excerpt and text search

- Caron, François. An Economic History of Modern France (1979) online edition

- Doyle, William. Old Regime France: 1648–1788 (2001) excerpt and text search

- Duby, Georges. France in the Middle Ages 987–1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc (1993), survey by a leader of the Annales School excerpt and text search

- Fierro, Alfred. Historical Dictionary of Paris (1998) 392pp, an abridged translation of his Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris (1996), 1580pp

- Goubert, Pierre. The Course of French History (1991), standard French textbook excerpt and text search; also complete text online

- Goubert, Pierre. Louis XIV and Twenty Million Frenchmen (1972), social history from Annales School

- Haine, W. Scott. The History of France (2000), 280 pp. textbook. and text search; also online edition

- Lucien Edward Henry (1882). "Signs of Times". The Royal Family of France: 17–38. Wikidata Q107258901.

- Holt, Mack P. Renaissance and Reformation France: 1500–1648 (2002) excerpt and text search

- Jones, Colin, and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie. The Cambridge Illustrated History of France (1999) excerpt and text search

- Jones, Colin. The Great Nation: France from Louis XV to Napoleon (2002) excerpt and text search

- Jones, Colin. Paris: Biography of a City (2004), 592pp; comprehensive history by a leading British scholar excerpt and text search

- Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel. The Ancien Régime: A History of France 1610–1774 (1999), survey by leader of the Annales School excerpt and text search

- Potter, David. France in the Later Middle Ages 1200–1500, (2003) excerpt and text search

- Potter, David. A History of France, 1460–1560: The Emergence of a Nation-State (1995)

- Price, Roger. A Concise History of France (1993) excerpt and text search

- Raymond, Gino. Historical Dictionary of France (2nd ed. 2008) 528pp

- Roche, Daniel. France in the Enlightenment (1998), wide-ranging history 1700–1789 excerpt and text search

- Wolf, John B. Louis XIV (1968), the standard scholarly biography online edition

Historiography

edit- Gildea, Robert. The Past in French History (1996)

- Nora, Pierre, ed. Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past (3 vol, 1996), essays by scholars; excerpt and text search; vol 2 excerpts; vol 3 excerpts

- Pinkney, David H. "Two Thousand Years of Paris", Journal of Modern History (1951) 23#3 pp. 262–264 in JSTOR

- Revel, Jacques, and Lynn Hunt, eds. Histories: French Constructions of the Past (1995). 654pp, 64 essays; emphasis on Annales School

- Symes, Carol. "The Middle Ages between Nationalism and Colonialism", French Historical Studies (Winter 2011) 34#1 pp 37–46

- Thébaud, Françoise. "Writing Women's and Gender History in France: A National Narrative?" Journal of Women's History (2007) 19#1 pp. 167–172 in Project MUSE

External links

edit- Media related to Kingdom of France at Wikimedia Commons

- Quotations related to Kingdom of France at Wikiquote

- Kingdom of France travel guide from Wikivoyage