Kids is a 1995 American drama film directed by Larry Clark in his directorial debut and written by Harmony Korine in his screenwriting debut.[4] It stars Leo Fitzpatrick, Justin Pierce and Chloë Sevigny in their film debuts. Fitzpatrick, Pierce, Sevigny, and other newcomers including Rosario Dawson portray a group of teenagers in New York City. They are characterized as hedonists, who engage in sexual acts and substance abuse, over the course of a single day.

| Kids | |

|---|---|

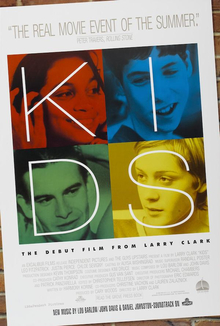

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Larry Clark |

| Written by | Harmony Korine |

| Produced by | Cary Woods |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Eric Edwards |

| Edited by | Christopher Tellefsen |

| Music by |

|

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Shining Excalibur Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5 million[2] |

| Box office | $20.4 million[3] |

Ben Detrick of the New York Times has described the film as "Lord of the Flies with skateboards, nitrous oxide and hip-hop... There is no thunderous moral reckoning, only observational detachment."[5] The film caused controversy upon its release in 1995 over its treatment of the subject matter. It received an NC-17 rating from the MPAA, but was released without a rating. Critical response was mixed, and the film grossed $20.4 million on a $1.5 million budget. It is now considered a cult classic.[6]

Plot

editIn an encounter that starts out consensually, a 17-year-old boy named Telly roughly has sex with a teen girl, despite her pleas for him to stop and be more gentle. Afterward, Telly meets with his best friend, Casper, and they discuss his sexual experience. He vocalizes his desire to keep having sex with virginal girls. They then enter a local store, where Casper shoplifts a bottle of malt liquor. Looking for drugs, food, and a place to hang out, they head to their friend Paul's apartment despite disliking him. They join the other boys in boasting about their sexual prowess and nonchalant attitudes to unprotected sex and venereal diseases.

Across the city, a group of girls are talking about sex. Their attitudes contradict that of the boys on many topics, particularly fellatio and the significance of the individuals to whom they lost their virginity. Two of the girls, Ruby and Jennie, mention that they were recently tested for sexually transmitted disease: Ruby tests negative, even though she has had multiple sexual encounters, and Jennie tests positive for HIV. She tells the nurse that she has had sex only once, with Telly. Distraught, she tries to find him to prevent him from passing HIV on to another girl. Meanwhile, Telly and Casper walk to Telly's house and steal money from his mother.

After purchasing marijuana, they gather with a few friends and, together, taunt a gay couple passing by. As Casper rides on a skateboard, he carelessly bumps into a man who angrily threatens and pushes him. The man is struck in the back of the head with a skateboard by Casper's friend Harold, causing him to collapse. Several other skaters join in, beating the man until he is rendered unconscious by a final blow to the head by Casper.

Telly and some of the group then pick up a 13-year-old girl named Darcy—the virginal younger sister of an acquaintance—with whom Telly wants to have sex, but Darcy shows restraint. Afterward, the group goes to an unsupervised party at the house of their friend Steven.

Jennie meets Misha, a girl who dislikes Casper and notes Telly's possible whereabouts at The Shelter. When Jennie arrives at the club, she runs into a boy named Fidget, who shoves a depressant into her mouth; she then learns Telly is at Steven's house. When Jennie arrives, Darcy and Telly have already begun having sex, which turns into rape, exposing Darcy to HIV. Jennie cries and passes out among the other partygoers.

The morning after, a drunk Casper rapes Jennie unprotected as she sleeps, unwittingly exposing himself to HIV. After a montage shows homeless people and drug users in the waking New York City, a voiceover by Telly says that sex is the only worthwhile thing in his life. A naked Casper says, "Jesus Christ, what happened?".

Cast

edit- Leo Fitzpatrick as Telly

- Justin Pierce as Casper

- Chloë Sevigny as Jennie

- Rosario Dawson as Ruby

- Yakira Peguero as Darcy

- Atabey Rodriguez as Misha

- Jon Abrahams as Steven

- Harold Hunter as Harold

- Sajan Bhagat as Paul

- Hamilton Harris as Hamilton

Sarah Henderson portrays the first girl Telly is seen having sex with. Tony Morales and Walter Youngblood portray the gay couple. Julie Stebe-Glorius and Christina Stebe-Glorious appear as Telly's mother and younger brother, respectively. The Rastafari is played by an actor credited as "Dr. Henry". Screenwriter Harmony Korine has an uncredited appearance as Fidget.

Production

editI wanted to present the way kids see things, but without all this baggage, this morality that these old middle aged Hollywood guys bring to it. Kids don't think that way...they're living in the moment not thinking about anything beyond that and that's what I wanted to catch.

– Larry Clark[7]

Larry Clark said that he wanted to "make the Great American Teenage Movie, like the Great American Novel."[8] The film is shot in a quasi-documentary style, although all of its scenes are scripted.

In Kids, Clark cast New York City "street" kids with no previous acting experience, notably Leo Fitzpatrick (Telly) and Justin Pierce (Casper).[9][10] Clark originally decided he wanted to cast Fitzpatrick in a film after watching him skateboard in New York, and cursing when he could not land certain tricks.[11] Korine had met Chloë Sevigny in New York before production began on Kids, and initially cast her in a small role as one of the girls in the swimming pool.[12] She was given the leading role of Jennie after Mia Kirshner, the original actress cast, was deemed not the right fit to work with first-time actors.[13][14][8] Sevigny and Korine went on to make Gummo (1997) and Julien Donkey-Boy (1999) together. Korine makes a cameo in the club scene with Jennie, as the kid wearing Coke-bottle glasses and a Nuclear Assault shirt who gives her drugs, though the part is credited to his brother Avi.

Korine reportedly wrote the film's screenplay in 1993, at the age of 18, and principal photography took place during the summer of 1994. Contrary to the perception of many viewers, the film, according to Korine, was almost entirely scripted, with the only exception being the scene with Casper on the couch at the end, which was improvised.[15] Gus Van Sant had been attached to the film as a producer.[14] After insufficient interest had been generated in the film, he left the project. Under incoming producer Cary Woods, the project found sufficient independent funding for the film.[14] Harvey Weinstein of Miramax, wary of parent The Walt Disney Company's opinion of the risky screenplay, declined to involve Disney in funding the production of the film. After Woods showed him the final cut, Miramax paid $3.5 million to buy the worldwide distribution rights of this film.[16]

Release

editMiramax Films, which was owned by The Walt Disney Company, paid $3.5 million to buy the worldwide distribution rights.[16] Later, Harvey and Bob Weinstein, the co-chairmen of Miramax Films, were forced to buy back the film from Disney and created Shining Excalibur Films, a one-off company, to release the film, due to Disney's policy, that at the time, forbid the release of NC-17 rated films, and the fact their appeal to the MPAA to lower it to R was denied. Eamonn Bowles was hired to be the chief operating officer of Shining Excalibur Films.[17][18]

The film, which cost $1.5 million to produce, grossed $7.4 million in the North American box office[3] and $20 million worldwide.[19] According to Peter Biskind's book Down and Dirty Pictures, Eamonn Bowles had stated that Harvey and Bob Weinstein might have personally profited up to $2 million each.[20]

Reception

editThe film received mixed reviews. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 47% based on 58 critic's reviews, with an average rating of 5.70/10. The site's consensus reads, "Kids isn't afraid to test viewers' limits, but the point of its nearly non-stop provocation is likely to be lost in all the repellent characters and unpleasant imagery".[21] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 63/100 based on reviews from 18 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[22]

The film was championed by some prominent critics, including Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, who gave the film three and a half out of four stars. "Kids is the kind of movie that needs to be talked about afterward. It doesn't tell us what it means. Sure, it has a 'message', involving safe sex. But safe sex is not going to civilize these kids, make them into curious, capable citizens. What you realize, thinking about Telly, is that life has given him nothing that interests him, except for sex, drugs and skateboards. His life is a kind of hell, briefly interrupted by orgasms."[23]

Janet Maslin of The New York Times called the film a "wake-up call to the modern world" about the nature of present-day youth in urban life.[24] She added it is also "an extremely difficult film to sit through, with an emphasis on societal disintegration and adolescent selfishness at its most sordid", and that some viewers will find issue with Clark's lack of judgement on the events depicted.[24] Some critics labeled it exploitative, describing it as borderline "child pornography".[25]

Other critics derided the film, with the most common criticism relating to the perceived lack of artistic merit. The Washington Post's Desson Thomson said, "Ostensibly about the banality of youthful evil, 'Kids' is simply about its own banality. At best, it's a misplaced aesthetic experiment. At worst, it's glossy exploitation—with enough controversy to launch a thousand trite radio and television talk shows."[26]

Feminist scholar bell hooks spoke extensively about the film in Cultural Criticism and Transformation: "Kids fascinated me as a film precisely because when you heard about it, it seemed like the perfect embodiment of the kind of postmodern, notions of journeying and dislocation and fragmentation and yet when you go to see it, it has simply such a conservative take on gender, on race, on the politics of HIV."[27]

In a 2016 retrospective essay about the film, writer Moira Weigel discussed the film's impact at the time of its release and legacy.[28] She acknowledged that the film "nails many of the ethnographic details of teen life in New York in the Nineties".[28] However, she commented on the film's depiction of HIV, writing:

"Watching it today, I was hoping for an account of the ways that the fear of AIDS shaped how young people in that time and place learned about desire. Instead the film recasts the virus into the threat lurking in the background of a kind of nightmare fairy tale...Rather than exploring how it shaped, and unmade, lives, it reduces the disease to one more slick bit of style, something to add suspense where the film might otherwise risk aimlessness and to heighten the aura of transgression. While it manages to capture the sense, instilled in us by our health teachers, that disease and death would be the price of desire, it does little more than that. Instead of examining the myths that loomed over the teen minds of that era, it enlarges them".[28]

Accolades

edit| Year | Award | Category | Recipients | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 1995 | Cannes Film Festival | Palme d'Or | Larry Clark | Nominated | [29] |

| Golden Camera | Nominated | ||||

| 1996 | Stinkers Bad Movie Awards | Worst Picture | Kids (Shining Excalibur) | Dishonourable Mention | [30][31] |

| March 23, 1996 | Independent Spirit Awards | Best Supporting Female | Chloë Sevigny | Nominated | [32][33][34] |

| Best First Screenplay | Harmony Korine | Nominated | |||

| Best First Feature | Kids (Shining Excalibur) | Nominated | |||

| Best Debut Performance | Justin Pierce | Won |

AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains

- Telly - Nominated Villain[35]

Documentary

editThe documentary We Were Once Kids was released in 2021.[36][37] Directed by Eddie Martin, it explores the film's production, as well as the post-film lives of some of the cast. At the time of filming Kids, most of the participating teenagers signed a contract without knowledge about their rights and were left on their own after filming ended.[6] The documentary was awarded for Best Editing at the Tribeca Film Festival.[38][39]

In popular culture

editIn August 2010, American rapper Mac Miller released the mixtape K.I.D.S., and its cover art, title, and some musical themes pay homage to the film. Some audio clips from the film are also part of the mixtape in between songs.[40]

On the film's twentieth anniversary in 2015, skateboarding brand Supreme launched a capsule collection commemorating the film.[41] Actors Justin Pierce and Harold Hunter had been involved with Supreme since its incarnation and were part of the brand's original skate team.[5]

Soundtrack

edit| Kids Original Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various artists | |

| Released | 1995 |

| Genre | |

| Length | 41:16 |

| Label | London |

| Producer |

|

| Singles from Kids Original Soundtrack | |

| |

The soundtrack was released in 1995.

In September 2023, Folk Implosion, the band composed of Lou Barlow and John Davis, released Music For Kids, a compilation of songs from the film, many of which had never been released for streaming, and others that had since become unavailable due to licensing issues. The album included songs that did not make the final cut, and alternate versions of the material present in the film.[43][44]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [42] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[45] |

| NME | 7/10[46] |

| Spin | 8/10[47] |

Creation of the film's soundtrack was overseen by Barlow.

- Daniel Johnston – "Casper"

- Deluxx Folk Implosion – "Daddy Never Understood"

- Folk Implosion – "Nothing Gonna Stop"

- Folk Implosion – "Jenny's Theme"

- Folk Implosion – "Simean Groove"

- Daniel Johnston – "Casper the Friendly Ghost"

- Folk Implosion – "Natural One"

- Sebadoh – "Spoiled"

- Folk Implosion – "Crash"

- Folk Implosion – "Wet Stuff"

- Lo-Down – "Mad Fright Night"

- Folk Implosion – "Raise the Bells"

- Slint – "Good Morning, Captain"

References

edit- ^ "Kids (18)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Kids (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Kids (1995) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ "Kids". Archived from the original on November 8, 2006. Retrieved January 12, 2007 – via Harmony-Korine.com.

- ^ a b Detrick, Ben (July 21, 2015). "'Kids,' Then and Now". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Kramer, Gary M. (June 12, 2021). "Revisiting the ethics of cult favorite "Kids" 26 years later through a new documentary". Salon. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Annear, Judy (2007). Photography: Art Gallery of New South Wales Collection. Art Gallery of New South Wales. p. 260. ISBN 9781741740066.

- ^ a b Bowen, Peter (1995). "The Little Rascals". Filmmaker. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved October 29, 2009 – via Harmony-Korine.com.

- ^ Taylor, Trey (July 28, 2015). "The behind the scenes stories from Kids you haven't heard". Dazed. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Hynes 2015, pp. 1-6.

- ^ "Leo Fitzpatrick, Unlimited". Interview Magazine. March 16, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Kennedy, Dana (March 12, 2000). "OSCAR FILMS/FIRST TIMERS; Who Says You Have to Struggle to Be a Star?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Hynes 2015, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Kohn, Eric (June 24, 2015). "Here's How 'Kids' Happened 20 Years Ago". IndieWire. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Lyons, Tom (October 16, 1997). "Southern Culture on the Skids". The Eye. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2009 – via Harmony-Korine.com.

- ^ a b "Controversy: 'Kids' For Adults". Newsweek. February 19, 1995. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Roman, Monica (January 7, 1998). "Roman, Monica; "Bowles distrib'n prez for Shooting Gallery: Ex-Goldwyn arthouse exec brings sound instincts to Gallery"; January 8, 1998". Variety. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ Evans, Greg (October 16, 1995). "It's Lights Out at Shining Excalibur". Variety. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (May 7, 1997). "Bookie bets on 'Paradise'". Variety.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (2004). Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance, and the Rise of Independent Film. Simon & Schuster. p. 215.

- ^ "Kids (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kids". Metacritic.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 28, 1995). "Kids Movie Review & Film Summary (1995)". Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (July 21, 1995). "FILM REVIEW: KIDS; Growing Up Troubled, In Terrifying Ways". The New York Times.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (August 25, 1995). "'Kids' (NR)". Washington Post. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ Thomson, Desson (August 25, 1995). "'Kids' (NR)". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Jhally, Sut (1997). Cultural Criticism & Transformation by bell hooks (PDF). Media Education Foundation. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ a b c Weigel, Moira (January 22, 2016). "Are the Kids All Right?". Lit Hub. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "Kids". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "Q & A with the Stinkers". The Stinkers. Archived from the original on April 13, 2001. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "Past Winners Database". theenvelope.latimes.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Dretzka, Gary (January 12, 1996). "Film Nominations Are Independent-minded". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "'Leaving Las Vegas' Arrives in Big Way at Spirit Awards". Los Angeles Times. March 25, 1996. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Independent Spirits Give Awards All Own". Chicago Tribune. March 25, 1996. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). American Film Institute. p. 62. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Kids | 2021 Tribeca Festival". Tribeca. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ Lang, Brent (June 12, 2021). "26 Years After 'Kids' Shocked the World, a New Documentary Examines the Lives It Shattered". Variety. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ "We Were Once Kids". Americana Film Fest. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (December 20, 2021). "Lightyear Entertainment Acquires Tribeca Docs 'A-ha: The Movie' And 'We Were Once Kids'". Deadline. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ "'Jesus Christ. What happened?': Larry Clark's 1995 'Kids' turns 20". MSNBC. July 31, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ "Supreme "KIDS 20th Anniversary" Capsule Collection". Hypebeast. May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Thomas Erlewine, Stephen. "Kids [Original Soundtrack] - Original Soundtrack | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ Gordon, Jeremy (September 4, 2023). "The Folk Implosion's Music From 'Kids' Is Returning. The Band Is, Too". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Berman, Stuart (September 9, 2023). "The Folk Implosion: Music for KIDS". Pitchfork. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Kids". Entertainment Weekly. Vol. #288. August 18, 1995. p. 55.

... it is as dark, beautiful, and uncommercial as the film it accompanies. ... But the haunting, gritty results are surprisingly addictive for a score ...

- ^ "Kids". NME. April 13, 1996. p. 49.

... a splendid record [that] ... pull[s] off the effortlessly cool dance fusion of rattly hip-hop beats and copyright-Barlow sonic doodles. ... [it] works, both as a collection of songs `inspired by' the film, and as a Folk Implosion extravaganza.

- ^ "Kids: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Spin. October 1995. p. 120. Retrieved July 8, 2024.

... the music to ... KIDS is an inextricable component. It provides a crucial emotional center in a brutally cold picture. ... Lou Barlow seems an unlikely choice to score the bulk of this street flick, but he's modified his music to fit KIDS's urban vibe ...

Works cited

edit- Hynes, Eric (July 16, 2015). "'Kids': The History of the 1990s' Most Controversial Film". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved July 8, 2024.