Khufu or Cheops (died c. 2566 BC) was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom period (26th century BC). Khufu succeeded his father Sneferu as king. He is generally accepted as having commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but many other aspects of his reign are poorly documented.[10][11]

| Khufu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheops, Suphis, Chnoubos,[1] Sofe[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Statue of Khufu in the Cairo Museum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | c. 2589 – c. 2566 BC[3][4] 28–29 years[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Sneferu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Djedefre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Meritites I, Henutsen[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Kawab, Djedefhor, Hetepheres II, Meritites II, Meresankh II, Baufra, Djedefre, Minkhaf I, Khafre, Khufukhaf I, Babaef, Horbaef, Nefertiabet, Khamerernebty I[9] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Pharaoh Sneferu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Queen Hetepheres I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | c. 2566 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Great Pyramid of Giza | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Great Pyramid of Giza, Khufu ship | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 4th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The only completely preserved portrait of the king is a small ivory figurine found in a temple ruin of a later period at Abydos in 1903. All other reliefs and statues were found in fragments, and many buildings of Khufu are lost. Everything known about Khufu comes from inscriptions in his necropolis at Giza and later documents.[citation needed] For example, Khufu is the main character noted in the Westcar Papyrus from the 13th dynasty.[10][11]

Most documents that mention king Khufu were written by ancient Egyptian and Greek historians around 300 BC.[citation needed] Khufu's obituary is presented there in a conflicting way: while the king enjoyed a long-lasting cultural heritage preservation during the period of the Old Kingdom and the New Kingdom, the ancient historians Manetho, Diodorus and Herodotus hand down a very negative depiction of Khufu's character. As a result, an obscure and critical picture of Khufu's personality persists.[10][11]

Khufu's name

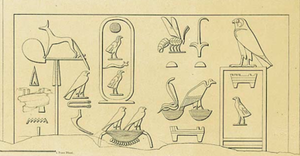

editKhufu's name was dedicated to the god Khnum, which might point to an increase of Khnum's popularity and religious importance. In fact, several royal and religious titles introduced at this time may point out that Egyptian pharaohs sought to accentuate their divine origin and status by dedicating their cartouche names (official royal names) to certain deities. Khufu may have viewed himself as a divine creator, a role that was already given to Khnum, the god of creation and growth. As a consequence, the king connected Khnum's name with his own. Khufu's full name (Khnum-khufu) means "Khnum protect me".[12][13] While modern Egyptological pronunciation renders his name as Khufu, at the time of his reign his name was probably pronounced as Kha(w)yafwi(y), and during the Hellenized era, Khewaf(w).[14]

The pharaoh officially used two versions of his birth name: Khnum-khuf and Khufu. The first (complete) version clearly exhibits Khufu's religious loyalty to Khnum, the second (shorter) version does not. It is unknown as to why the king would use a shortened name version since it hides the name of Khnum and the king's name connection to this god. It might be possible though, that the short name was not meant to be connected to any god at all.[10][11]

Khufu is well known under his Hellenized name Χέοψ, Khéops or Cheops (/ˈkiːɒps/, KEE-ops, by Diodorus and Herodotus) and less well known under another Hellenized name, Σοῦφις, Súphis (/ˈsuːfɪs/, SOO-fis, by Manetho).[10][11] A rare version of the name of Khufu, used by Josephus, is Σόφε, Sofe (/ˈsɒfi/, SOF-ee).[2] (The pronunciations given here are for English; the pronunciations in Ancient Greek were different.) Arab historians, who wrote mystic stories about Khufu and the Giza pyramids, called him Saurid (Arabic: سوريد) or Salhuk (سلهوق).[15]

Family

editKhufu's origin

editThe royal family of Khufu was quite large. It is uncertain if Khufu was actually the biological son of Sneferu. Egyptologists believe Sneferu was Khufu's father, but only because it was handed down by later historians that the eldest son or a selected descendant would inherit the throne.[9] In 1925 the tomb of queen Hetepheres I, G 7000x, was found east of Khufu's pyramid. It contained many precious grave goods, and several inscriptions give her the title Mut-nesut (meaning "mother of a king"), together with the name of king Sneferu. Therefore, it seemed clear at first that Hetepheres was the wife of Sneferu, and that they were Khufu's parents. More recently, however, some have doubted this theory, because Hetepheres is not known to have borne the title Hemet-nesut (meaning "king's wife"), a title indispensable to confirm a queen's royal status.[9][16]

Instead of the spouse's title, Hetepheres bore only the title Sat-netjer-khetef (verbatim: "daughter of his divine body"; symbolically: "king's bodily daughter"), a title mentioned for the first time.[16] As a result, researchers now think Khufu may not have been Sneferu's biological son, but that Sneferu legitimised Khufu's rank and familial position by marriage. By apotheosizing his mother as the daughter of a living god, Khufu's new rank was secured. This theory may be supported by the circumstance that Khufu's mother was buried close to her son and not in the necropolis of her husband, as it was to be expected.[9][16][17]

Family tree

editThe following list presents family members, which can be assigned to Khufu with certainty.

Parents:[9][16][17]

- Sneferu: Most possibly his father, maybe just his stepfather. Famous pharaoh and builder of three pyramids.

- Hetepheres I: Most possibly his mother. Wife of king Sneferu and well known for her precious grave goods found at Giza.

- Meritites I: First wife of Khufu

- Henutsen: Second wife of Khufu. She is mentioned on the famous Inventory Stela.

Brothers and sisters:[9][16][17]

- Hetepheres: Wife of Ankhhaf

- Ankhhaf: The eldest brother. His nephew would later become pharaoh Khafra.

- Nefermaat: Half-brother; buried at Meidum and owner of the famous "mastaba of the geese"

- Rahotep: Elder brother or half-brother. Owner of a life-size double statue portraying him and his wife Nofret, displayed in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo.

- Kawab: Most possibly the eldest son and crown prince, he died before Khufu's own end of reign and thus did not follow Khufu on the throne.

- Djedefra: Also known as Radjedef and Ratoises. Became the first throne successor.

- Khafre: Most possibly second throne successor

- Djedefhor: Also known as Hordjedef. Mentioned in the Papyrus Westcar

- Baufra: Possibly a son of Khufu, but neither archaeologically nor contemporarily attested. Only known from two much later documents.

- Babaef I: Also known as Khnum-baef I

- Khufukhaf I: Also known as Kaefkhufu I

- Minkhaf I

- Horbaef

- Nefertiabet: Known for her beautiful slab stelae

- Hetepheres II: Wife of prince Kawab, later married to pharaoh Djedefra

- Meresankh II

- Meritites II: Married to Akhethotep

- Khamerernebty I: Wife of king Khafra and mother of Menkaura

- Duaenhor: Son of Kawab and possibly eldest grandchild

- Kaemsekhem: Second son of Kawab

- Mindjedef: Also known as Djedefmin

- Djaty: Son of Horbaef

- Iunmin I: Son of Khafre

Nephews and nieces:[9][16][17]

- Hemiunu: Director of the building of Khufu's great pyramid

- Nefertkau III: Daughter of Meresankh II

- Djedi: Son of Rahotep and Nofret

- Itu: Son of Rahotep and Nofret

- Neferkau: Son of Rahotep and Nofret

- Mereret: Daughter of Rahotep and Nofret

- Nedjemib: Daughter of Rahotep and Nofret

- Sethtet: Daughter of Rahotep and Nofret

Reign

editLength of reign

editIt is still unclear how long exactly Khufu ruled over Egypt. Dates from Khufu's final years suggest that he was approaching his 30-year jubilee, but may have just missed it.[19]

One of them was found at the Dakhla Oasis in the Libyan Desert. Khufu's serekh name is carved in a rock inscription reporting the "Mefat-travelling in the year after the 13th (biennial) cattle count under Hor-Medjedu", reignal year 27.[20]

Several papyrus fragments, known as the Diary of Merer, were found at Khufu's harbor at Wadi al-Jarf. They log the transport of limestone blocks from Tura to the Great Pyramid of Giza in the "year after the 13th cattle count under Hor-Medjedw".[21][22]

The highest known date from Khufu's reign is related to his funeral. Four instances of graffiti from the western of two rock-cut pits along the south side of the Great Pyramid attest to a date from the 28th or 29th reignal year of Khufu: the 14th census, month 1 of the season Shemu (our spring-early summer).[19]

The Royal Canon of Turin from the 19th Dynasty, gives 23 years of rulership for Khufu.[10][23] The ancient historian Herodotus gives 50 years, and the ancient historian Manetho even credits him 63 years of reign. These figures are now considered an exaggeration or a misinterpretation of antiquated sources.[10]

Political activities

editThere are only a few hints about Khufu's political activities within and outside Egypt. Within Egypt, Khufu is documented in several building inscriptions and statues. Khufu's name appears in inscriptions at Elkab and Elephantine and in local quarries at Hatnub and Wadi Hammamat. At Saqqara two terracotta figures of the goddess Bastet were found, on which, at their bases, the horus name of Khufu is incised. They were deposited at Saqqara during the Middle Kingdom, but their creation can be dated back to Khufu's reign.[24]

Wadi Maghareh

editAt Wadi Maghareh in the Sinai a rock inscription depicts Khufu with the double crown. Khufu sent several expeditions in an attempt to find turquoise and copper mines. Like other kings, such as Sekhemkhet, Sneferu and Sahure, who are also depicted in impressive reliefs there, he was looking for those two precious materials.[25] Khufu also entertained contacts with Byblos. He sent several expeditions to Byblos in an attempt to trade copper tools and weapons for precious Lebanon cedar wood. This kind of wood was essential for building large and stable funerary boats and indeed the boats discovered at the Great Pyramid were made of it.[26]

Wadi al-Jarf

editNew evidence regarding political activities under Khufu's reign has recently been found at the site of the ancient port of Wadi al-Jarf on the Red Sea coast in the east of Egypt. The first traces of such a harbour were excavated in 1823 by John Gardner Wilkinson and James Burton, but the site was quickly abandoned and then forgotten over time. In 1954, French scholars François Bissey and René Chabot-Morisseau re-excavated the harbour, but their works were brought to an end by the Suez Crisis in 1956. In June 2011, an archaeological team led by French Egyptologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard, organized by the French Institute of Oriental Archeology (IFAO), restarted work at the site. Among other material, a collection of hundreds of papyrus fragments were found in 2013 dating back 4500 years.[21][22] The papyrus is currently exhibited at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass called this ancient papyrus “the greatest discovery in Egypt in the 21st century.”[27][28][29][30][31]

Ten of these papyri are very well preserved. The majority of these documents date to the 27th year of Khufu's reign and describe how the central administration sent food and supplies to the sailors and wharf workers. The dating of these important documents is secured by phrases typical for the Old Kingdom period, as well as the fact that the letters are addressed to the king himself, using his Horus name. This was typical when the king in question was still alive; when the ruler was dead he was addressed by his cartouche name or birth name. One document is of special interest: the diary of Merer, an official involved in the building of the Great Pyramid. Using the diary, researchers were able to reconstruct three months of his life, providing new insight into the everyday lives of people of the Fourth Dynasty. These papyri are the earliest examples of imprinted papyri ever found in Egypt. Another inscription, found on the limestone walls of the harbor, mentions the head of the royal scribes controlling the exchange of goods: Idu.[21][22]

Khufu's cartouche name is also inscribed on some of the heavy limestone blocks at the site. The harbor was of strategic and economic importance to Khufu because ships brought precious materials, such as turquoise, copper and ore from the southern tip of the Sinai peninsula. The papyri fragments show several storage lists naming the delivered goods. The papyri also mention a certain harbour at the opposite coast of Wadi al-Jarf, on the western shore of the Sinai Peninsula, where the ancient fortress Tell Ras Budran was excavated in 1960 by Gregory Mumford. The papyri and the fortress together reveal an explicit sailing route across the Red Sea for the very first time in history. It is the oldest archaeologically detected sailing route of Ancient Egypt. According to Tallet, the harbor could also have been one of the legendary high sea harbours of Ancient Egypt, from where expeditions to the infamous gold land Punt had started.[21][22]

Monuments and statues

editStatues

editThe only three-dimensional depiction of Khufu that has survived time nearly completely is a small and well restored ivory figurine known as the Khufu Statuette. It shows the king with the Red Crown of Lower Egypt.[32] The king is seated on a throne with a short backrest, at the left side of his knees the Horus-name Medjedu is preserved, and, at the right side, a fragment of the lower part of the cartouche name Khnum-Khuf is visible. Khufu holds a flail in his left hand and his right hand rests together with his lower arm on his right upper leg. The artifact was found in 1903 by Flinders Petrie at Kom el-Sultan near Abydos. The figurine was found headless; according to Petrie, it was caused by an accident while digging. When Petrie recognized the importance of the find, he stopped all other work and offered a reward to any workman who could find the head. Three weeks later the head was found after intense sifting in a deeper level of the room rubble.[33]

Today the little statue is restored and on display in the Egyptian Museum of Cairo in room 32 under its inventory number JE 36143.[34] Most Egyptologists believe the statuette is contemporary, but some scholars, such as Zahi Hawass, think that it was an artistic reproduction of the 26th dynasty. He argues[where?] that no building that clearly dates to the Fourth Dynasty was ever excavated at Kom el-Sultan or Abydos. Furthermore, he points out that the face of Khufu is unusually squat and chubby and shows no emotional expression. Hawass compared the facial stylistics with statues of contemporary kings, such as Sneferu, Khaefra and Menkaura. The faces of these three kings are of even beauty, slender and with a kindly expression—the clear result of idealistic motivations; they are not based on reality. The appearance of Khufu on the ivory statue instead looks like the artist did not care very much about professionalism or diligence.[32][34]

He believes Khufu himself would never have allowed the display of such a comparatively sloppy work. And finally, Hawass also argues that the sort of throne the figurine sits on does not match the artistic styles of any Old Kingdom artifact. Old Kingdom thrones had a backrest that reached up to the neck of the king. But the ultimate proof that convinces Hawass about the statue being a reproduction of much later time is the Nehenekh flail in Khufu's left hand. Depictions of a king with such a flail as a ceremonial insignia appear no earlier than the Middle Kingdom. Zahi Hawass therefore concludes that the figurine was possibly made as an amulet or lucky charm to sell to pious citizens.[32][34]

Deitrich Wildung has examined the representation of Nubian features in Egyptian iconography since the predynastic era and has argued that Khufu had these specific, Nubian features and this was represented in his statues.[35]

Excavations at Saqqara in 2001 and 2003 revealed a pair of terracotta statues depicting a lion goddess (possibly Bastet or Sekhmet). On her feet two figures of childlike kings are preserved. While the right figurine can be identified as king Khufu by his Horus name, the left one depicts king Pepy I of 6th dynasty, called by his birth name. The figurines of Pepy were added to the statue groups in later times, because they were placed separately and at a distance from the deity.[36]

This is inconsistent with a typical statue group of the Old Kingdom—normally all statue groups were built as an artistic unit. The two statue groups are similar to each other in size and scale but differ in that one lion goddess holds a scepter. The excavators point out that the statues were restored during the Middle Kingdom, after they were broken apart. However, it seems that the reason for the restoration lay more in an interest in the goddess, than in a royal cult around the king figures: their names were covered with gypsum.[37]

The Palermo Stone reports on its fragment C-2 the creation of two oversize standing statues for the king; one is said to have been made of copper, the other of pure gold.[10][32]

Furthermore, several alabaster and travertine fragments of seated statues, which were found by George Reisner during his excavations at Giza, were once inscribed with Khufu's full royal titulary. Today, the complete or partially preserved cartouches with the name Khufu or Khnum-Khuf remain. One of the fragments, that of a small seated statue, shows the legs and feet of a sitting king from the knuckles downward. To the right of them the name ...fu in a cartouche is visible, and it can easily be reconstructed as the cartouche name Khufu.[32][38]

Two further objects are on display at the Roemer- und Pelizaeus-Museum Hildesheim. These are also made of alabaster. One of them shows the head of a cat goddess (most probably Bastet or Sekhmet). The position of her right arm suggests that the bust once belonged to a statue group similar to the well-known triad of Mycerinus.[39]

Several statue heads might have belonged to Khufu. One of them is the so-called "Brooklyn head" of the Brooklyn Museum in New York City. It is 54.3 cm large and made of pink granite. Because of its chubby cheeks the head is assigned to Khufu as well as to king Huni.[40] A similar object is on display at the State Collection of Egyptian Art in Munich. The head is made of limestone and is comparatively small at only 5.7 cm.[41]

Reliefs

editKhufu is depicted in several relief fragments found scattered in his necropolis and elsewhere. All reliefs were made of finely polished limestone. Some of them originate from the ruined pyramid temple and the destroyed causeway, where they once covered the walls completely. Others were found re-used in the pyramid necropolis of king Amenemhet I at Lisht and at Tanis and Bubastis.[10][32] One of the relief fragments shows the cartouche of Khufu with the phrase: "Building of the sanctuaries of the gods". Another one shows a row of fat oxen decorated with flowers—they were prepared as sacrifices during an offering procession. The guiding inscription calls them "the surroundings of Tefef serve Khufu", "beautiful bulls of Khufu" and "bawling for Khufu".[42] A third one shows the earliest known depiction of royal warfare: the scene is called "archers prepare", since it shows archers drawing their bows. And a fourth example shows the king with the double crown impaling a hippopotamus.[43][44]

At the Wadi Maghareh in Sinai a rock inscription contains Khufu's names and titles and reports: "Hor-Medjedu, Khnum-Khuf, Bikuj-Nebu, the great god and smiter of the troglodytes, all protection and life are with him". The work-off of the relief is similar to that of king Snefru. In one scene king Khufu wears the double-crown; nearby, the depiction of the god Thoth is visible. In another scene, close by, Khufu wears the Atef-crown while smiting an enemy. In this scene the god Wepwawet is present.[25][45]

None of the numerous relief fragments shows king Khufu offering to a god. This is remarkable, since reliefs of Sneferu and those of all kings from Menkaura onward show the king offering to a deity. It is possible that the lack of this special depiction influenced later ancient Greek historians in their assumptions that Khufu could have actually closed all temples and prohibited any sacrifice.[32][46]

Pyramid complex

editThe pyramid complex of Khufu was erected in the northeastern section of the plateau of Giza. It is possible that the lack of building space, the lack of local limestone quarries and the loosened ground at Dahshur forced Khufu to move north, away from the pyramid of his predecessor Sneferu. Khufu chose the high end of a natural plateau so that his future pyramid would be widely visible. Khufu decided to call his pyramid Akhet-Khufu (meaning "horizon of Khufu").[47][48][49][50]

The Great Pyramid has a base measurement of ca. 750 x 750 ft (≙ 230.4 x 230.4 m) and today a height of 455.2 ft (138.7 m). Once it had been 481 ft (147 m) high, but the pyramidion and the limestone casing are completely lost due to stone robbery. The lack of the casing allows a full view of the inner core of the pyramid. It was erected in small steps by more or less roughly hewn blocks of dark limestone. The casing was made of nearly white limestone. The outer surface of the casing stones were finely polished so the pyramid shimmered in bright, natural lime-white when new. The pyramidion might have been covered in electrum, but there is no archaeological proof of that. The inner corridors and chambers have walls and ceilings made of polished granite, one of the hardest stones known in Khufu's time. The mortar used was a mixture of gypsum, sand, pulverized limestone and water.[47][48][49]

The original entrance to the pyramid is on the northern side. Inside the pyramid are three chambers: at the top is the burial chamber of the king (the king's chamber), in the middle is the statue chamber (erroneously called the queen's chamber), and under the foundation is an unfinished subterranean chamber (underworld chamber). Whilst the burial chamber is identified by its large sarcophagus made of granite, the use of the "queen's chamber" is still disputed—it might have been the serdab of the Ka statue of Khufu. The subterranean chamber remains mysterious as it was left unfinished.[47][48][49]

A tight corridor heading south at the western end of the chamber and an unfinished shaft at the eastern middle might indicate that the subterranean chamber was the oldest of the three chambers and that the original building plan contained a simple chamber complex with several rooms and corridors. But for unknown reasons the works were stopped and two further chambers were built inside the pyramid. Remarkable is the so-called Grand Gallery leading to the king's chamber: It has a corbelled arch ceiling and measures 28.7 ft (8.7 m) in height and 151.3 ft (46.1 m) in length. The gallery has an important static function; it diverts the weight of the stone mass above the king's chamber into the surrounding pyramid core.[47][48][49]

Khufu's pyramid was surrounded by an enclosure wall, with each segment 33 ft (10 m) in distance from the pyramid. On the eastern side, directly in front of the pyramid, Khufu's mortuary temple was built. Its foundation was made of black basalt, a great part of which is still preserved. Pillars and portals were made of red granite and the ceiling stones were of white limestone. Today nothing remains but the foundation. From the mortuary temple a causeway 0.43 miles long once connected to the valley temple. The valley temple was possibly made of the same stones as the mortuary temple, but since even the foundation is not preserved, the original form and size of the valley temple remain unknown.[47][48][49][50]

On the eastern side of the pyramid lies the East Cemetery of the Khufu necropolis, containing the mastabas of princes and princesses. Three small satellite pyramids, belonging to the queens Hetepheres (G1-a), Meritites I (G1-b) and possibly Henutsen (G1-c) were erected at the southeast corner of Khufu's pyramid. Close behind the queens' pyramids G1-b and G1-c, the cult pyramid of Khufu was found in 2005. On the southern side of the Great Pyramid lie some further mastabas and the pits of the funerary boats of Khufu. On the western side lies the West Cemetery, where the highest officials and priests were interred.[47][48][49][50]

A possible part of Khufu's funerary complex is the famous Great Sphinx of Giza. It is a 241 ft × 66.6 ft (73.5 m × 20.3 m) large limestone statue in the shape of a recumbent lion with the head of a human, decorated with a royal Nemes headdress. The Sphinx was directly hewn out of the plateau of Giza and originally painted with red, ochre, green and black. To this day it is passionately disputed as to who exactly gave the order to build it: the most probable candidates are Khufu, his elder son Djedefra and his younger son Khaefra. One of the difficulties of a correct attribution lies in the lack of any perfectly preserved portrait of Khufu. The faces of Djedefre and Khaefra are both similar to that of the Sphinx, but they do not match perfectly. Another riddle is the original cultic and symbolic function of the Sphinx. Much later it was called Heru-im-Akhet (Hârmachís; "Horus at the horizon") by the Egyptians and Abu el-Hὀl ("father of terror") by the Arabians. It might be that the Sphinx, as an allegoric and mystified representation of the king, simply guarded the sacred cemetery of Giza.[47][48][49][50]

Khufu in later Egyptian traditions

editOld Kingdom

editKhufu possessed an extensive mortuary cult during the Old Kingdom. At the end of 6th dynasty at least 67 mortuary priests and 6 independent high officials serving at the necropolis are archaeologically attested. Ten of them were already serving during the late 4th dynasty (seven of them were royal family members), 28 were serving during the 5th dynasty and 29 during the 6th dynasty. This is remarkable: Khufu's famous (step-)father Sneferu enjoyed "only" 18 mortuary priesthoods during the same period of time, even Djedefra enjoyed only 8 and Khaefra enjoyed 28. Such mortuary cults were very important for the state's economy, because for the oblations special domains had to be established. A huge number of domains' names are attested for the time of Khufu's reign. However, by the end of the 6th dynasty the number of domains abated quickly. With the beginning of the 7th dynasty no domain's name was handed down any more.[10][11][51]

Middle Kingdom

editAt Wadi Hammamat a rock inscription dates back to the 12th dynasty. It lists five cartouche names: Khufu, Djedefra, Khafra, Baufra and Djedefhor. Because all royal names are written inside cartouches, it was often believed that Baufra and Djedefhor once had ruled for short time, but contemporary sources entitle them as mere princes. Khufu's attendance roll call in this list might indicate that he and his followers were worshipped as patron saints. This theory is promoted by findings such as alabaster vessels with Khufu's name found at Koptos, the pilgrimage destination of Wadi Hammamat travellers.[9][16][17]

A literary masterpiece from the 13th dynasty talking about Khufu is the famous Papyrus Westcar, where king Khufu witnesses a magical wonder and receives a prophecy from a magician named Dedi. Within the story, Khufu is characterised in a difficult-to-assess way. On one hand, he is depicted as ruthless when deciding to have a condemned prisoner decapitated to test the alleged magical powers of Dedi. On the other hand, Khufu is depicted as inquisitive, reasonable and generous: He accepts Dedi's outrage and his subsequent alternative offer for the prisoner, questions the circumstances and contents of Dedi's prophecy and rewards the magician generously after all. The contradictory depiction of Khufu is the subject of great dispute between Egyptologists and historians to this day. Especially earlier Egyptologists and historians such as Adolf Erman, Kurt Heinrich Sethe and Wolfgang Helck evaluated Khufu's character as heartless and sacrilegious. They leaned on the ancient Greek traditions of Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, who described an exaggerated negative character image of Khufu, ignoring the paradoxical (because positive) traditions the Egyptians themselves had always taught.[51][52][53][54][55]

But other Egyptologists, such as Dietrich Wildung, see Khufu's order as an act of mercy: the prisoner would have received his life back if Dedi had actually performed his magical trick. Wildung thinks that Dedi's refusal was an allusion to the respect Egyptians showed to human life. The ancient Egyptians were of the opinion that human life should not be misused for dark magic or similar evil things. Verena Lepper and Miriam Lichtheim suspect that a difficult-to-assess depiction of Khufu was exactly what the author had planned. He wanted to create a mysterious character.[51][52][53][54][55]

New Kingdom

editDuring the New Kingdom the necropolis of Khufu and the local mortuary cults were reorganized and Giza became an important economic and cultic destination again. During the Eighteenth Dynasty king Amenhotep II erected a memorial temple and a royal fame stele close to the Great Sphinx. His son and throne follower Thutmose IV freed the Sphinx from sand and placed a memorial stele—known as the "Dream Stele"—between its front paws. The two steles' inscriptions are similar in their narrative contents, but neither of them gives specific information about the true builder of the Great Sphinx.[10][11][51]

At the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty a temple for the goddess Isis was built at the satellite pyramid G1-c (that of queen Henutsen) at Khufu's necropolis. During the Twenty-first Dynasty the temple got extended, and, during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, the extensions continued. From this period of time several "priests of Isis" (Hem-netjer-Iset), who were also "priests of Khufu" (Hem-netjer-Khufu), worked there. From the same dynasty a golden seal ring with the name of a priest Neferibrê was found at Giza.[10][11][51]

Late Period

editDuring the Late Period huge numbers of scarabs with the name of Khufu were sold to the citizens, possibly as some kind of lucky charms. More than 30 scarabs are preserved. At Isis' temple a family tree of the Isis priests is on display, which lists the names of priests from 670 to 488 BC. From the same period comes the famous Inventory Stela, which names Khufu and his wife Henutsen. However, modern Egyptologists question whether Khufu was still personally adored as a royal ancestor at this time; they think it more likely that Khufu was already seen as a mere symbolic foundation figure for the history of the Isis temple.[10][11][51][56]

Khufu in ancient Greek traditions

editManetho

editThe later Egyptian historian Manetho called Khufu "Sûphis" and credited him with a rulership of 63 years. He also mentions that Khufu built the Great Pyramid, then he claims that his contemporary Herodotus says that the pyramid was built by a king "Khéops". Manetho thought "Khéops" and "Sûphis" to be two different kings. Manetho also says that Khufu received a contempt against the gods and that he had written a sacred book about that and that he (Manetho) received that book during his travel through Egypt. The story about the alleged "Sacred Book" is questioned by modern Egyptologists, for it would be highly unusual that a pharaoh wrote books and that such a precious document could be sold away so easily.[57][58][59]

Herodotus

editThe Greek historian Herodotus instead depicts Khufu as a heretic and cruel tyrant. In his literary work Historiae, Book II, chapter 124–126, he writes: "As long as Rhámpsinîtos was king, as they told me, there was nothing but orderly rule in Egypt, and the land prospered greatly. But after him Khéops became king over them and brought them to every kind of suffering: He closed all the temples; after this he kept the priests from sacrificing there and then he forced all the Egyptians to work for him. So some were ordered to draw stones from the stone quarries in the Arabian mountains to the Nile, and others he forced to receive the stones after they had been carried over the river in boats, and to draw them to those called the Libyan mountains. And they worked by 100,000 men at a time, for each three months continually. Of this oppression there passed ten years while the causeway was made by which they drew the stones, which causeway they built, and it is a work not much less, as it appears to me, than the pyramid. For the length of it is 5 furlongs and the breadth 10 fathoms and the height, where it is highest, 8 fathoms, and it is made of polished stone and with figures carved upon it. For this, they said, 10 years were spent, and for the underground chambers on the hill upon which the pyramids stand, which he caused to be made as sepulchral chambers for himself in an island, having conducted thither a channel from the Nile.

For the making of the pyramid itself there passed a period of 20 years; and the pyramid is square, each side measuring 800 feet, and the height of it is the same. It is built of stone smoothed and fitted together in the most perfect manner, not one of the stones being less than 30 feet in length. This pyramid was made after the manner of steps, which some call 'rows' and others 'bases': When they had first made it thus, they raised the remaining stones with devices made of short pieces of timber, lifting them first from the ground to the first stage of the steps, and when the stone got up to this it was placed upon another machine standing on the first stage, and so from this it was drawn to the second upon another machine; for as many as were the courses of the steps, so many machines there were also, or perhaps they transferred one and the same machine, made so as easily to be carried, to each stage successively, in order that they might take up the stones; for let it be told in both ways, according as it is reported. However, that may be, the highest parts of it were finished first, and afterwards they proceeded to finish that which came next to them, and lastly they finished the parts of it near the ground and the lowest ranges.

On the pyramid it is declared in Egyptian writing how much was spent on radishes and onions and leeks for the workmen, and if I remember correctly what the interpreter said while reading this inscription for me, a sum of 1600 silver talents was spent. Kheops moreover came to such a pitch of evilness, that being in want of money he sent his own daughter to a brothel and ordered her to obtain from those who came a certain amount of money (how much it was they did not tell me). But she not only obtained the sum that was appointed by her father, but she also formed a design for herself privately to leave behind her a memorial: She requested each man who came in to her to give her one stone for her building project. And of these stones, they told me, the pyramid was built which stands in front of the great pyramid in the middle of the three, each side being 150 feet in length."[51][58][59]

The same goes for the story about king Khafre. He is depicted as the direct follower of Khufu and as likewise evil and that he ruled for 56 years. In chapter 127–128 Herodotus writes: "After Khéops was dead his brother Khéphrên succeeded to the royal throne. This king followed the same manner as the other ... and ruled for 56 years. Here they reckon altogether 106 years, during which they say that there was nothing but evil for the Egyptians, and the temples were kept closed and not opened during all that time".[51][58][59]

Herodotus closes the story of the evil kings in chapter 128 with the words: "These kings the Egyptians (because of their hate against them) are not very willing to say their names. What's more, they even call the pyramids after the name of Philítîs the shepherd, who at that time pastured flocks in those regions."[51][58][59]

Diodorus of Sicily

editThe ancient historian Diodorus claims that Khufu was so much abhorred by his own people in later times that the mortuary priests secretly brought the royal sarcophagus, together with the corpse of Khufu, to another, hidden grave. With this narration he strengthens and confirms the view of the Greek scholars, that Khufu's pyramid (and the other two, as well) must have been the result of slavery. However, at the same time, Diodorus distances himself from Herodotus and argues that Herodotus "only tells fairy tales and entertaining fiction". Diodorus claims that the Egyptians of his lifetime were unable to tell him with certainty who actually built the pyramids. He also states that he did not really trust the interpreters and that the true builder might have been someone different: the Khufu pyramid was (according to him) built by a king named Harmais, the Khafre pyramid was thought to be built by king Amasis II and the Menkaura pyramid was allegedly the work of king Inaros I.[23]

Diodorus states that the Khufu pyramid was beautifully covered in white, but the top was said to be capped. The pyramid therefore already had no pyramidion anymore. He also thinks that the pyramid was built with ramps, which were removed during the finishing of the limestone shell. Diodorus estimates that the total number of workers was 300,000 and that the building works lasted for 20 years.[23]

Khufu in Arabic traditions

editIn AD 642, the Arabs conquered Egypt. Upon arriving at the Giza pyramids, they searched for explanations as to who could have built these monuments. By this time, no inhabitant of Egypt was able to tell and no one could translate the Egyptian hieroglyphs anymore. As a consequence, the Arab historians wrote down their own theories and stories.[60]

The best known story about Khufu and his pyramid can be found in the book Hitat (completely: al-Mawāʿiẓ wa-’l-iʿtibār fī ḏikr al-ḫiṭaṭ wa-’l-ʾāṯār), written in 1430 by Muhammad al-Maqrizi (1364–1442). This book contains several collected theories and myths about Khufu, especially about the Great Pyramid. Though King Khufu himself is seldom mentioned, many Arab writers were convinced that the Great Pyramid (and the others, too) were built by the god Hermes (named Idris by the Arabs).[60]

Al-Maqrizi notes that Khufu was named Saurid, Salhuk and/or Sarjak by the biblical Amalekites. Then he writes that Khufu built the pyramids after repeated nightmares in which the earth turned upside-down, the stars fell down and people were screaming in terror. Another nightmare showed the stars falling down from heaven and kidnapping humans, then putting them beneath two large mountains. King Khufu then received a warning from his prophets about a devastating deluge that would come and destroy Egypt. To protect his treasures and books of wisdom, Khufu built the three pyramids of Giza.[60]

Modern egyptological evaluations

editOver time, Egyptologists examined possible motives and reasons as to how Khufu's reputation changed over time. Closer examinations of and comparisons between contemporary documents, later documents and Greek and Coptic readings reveal that Khufu's reputation changed slowly, and that the positive views about the king still prevailed during the Greek and Ptolemaic era.[61] Alan B. Lloyd, for example, points to documents and inscriptions from the 6th dynasty listing an important town called Menat-Khufu, meaning "nurse of Khufu". This town was still held in high esteem during the Middle Kingdom period. Lloyd is convinced that such a heart-warming name wouldn't have been chosen to honour a king with a bad (or, at least, questionable) reputation. Furthermore, he points to the overwhelming number of places where mortuary cults for Khufu were practiced, even outside Giza. These mortuary cults were still practiced even in Saitic and Persian periods.[61]

The famous Lamentation Texts from the First Intermediate Period reveal some interesting views about the monumental tombs from the past; they were at that time seen as proof of vanity. However, they give no hint of a negative reputation of the kings themselves, and thus they do not judge Khufu in a negative way.[61]

Modern Egyptologists evaluate Herodotus's and Diodorus's stories as some sort of defamation, based on both authors' contemporary philosophy. They call for caution against the credibility of the ancient traditions. They argue that the classical authors lived around 2000 years after Khufu, and their sources that were available in their lifetimes surely were antiquated.[51][58] Additionally some Egyptologists point out that the philosophies of the ancient Egyptians had changed since the Old Kingdom. Oversized tombs such as the Giza pyramids must have appalled the Greeks and even the later priests of the New Kingdom, because they remembered the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten and his megalomaniac building projects.[58][59]

This negative picture was presumably projected onto Khufu and his pyramid. The view was possibly promoted by the fact that during Khufu's lifetime, permission for the creation of oversized statues made of precious stone and their displaying in public was limited to the king.[11][51] In their era, the Greek authors, mortuary priests, and temple priests could only explain the impressive monuments and statues of Khufu as the result of a megalomaniac. These negative evaluations were applied to Khufu.[58][59]

Furthermore, several Egyptologists point out that Roman historians such as Pliny the Elder and Frontinus (both around AD 70) equally do not hesitate to ridicule the pyramids of Giza: Frontinus calls them "idle pyramids, containing the indispensable structures likewise to some of our abandoned aqueducts at Rome" and Pliny describes them as "the idle and foolish ostentation of royal wealth". Egyptologists clearly see politically and socially motivated intentions in these criticisms and it seems paradoxical that the use of these monuments was forgotten, but the names of their builders remained immortalized.[62]

Another hint to Khufu's bad reputation within the Greek and Roman folk might be hidden in the Coptic reading of Khufu's name. The Egyptian hieroglyphs forming the name "Khufu" are read in Coptic as "Shêfet", which actually would mean "bad luck" or "sinful" in their language. The Coptic reading derives from a later pronunciation of Khufu as "Shufu", which in turn led to the Greek reading "Suphis". Possibly the bad meaning of the Coptic reading of "Khufu" was unconsciously copied by the Greek and Roman authors.[61]

On the other hand, some Egyptologists think that the ancient historians received their material for their stories not only from priests, but from the citizens living close to the time of the building of the necropolis.[63] Among the "simple folk", also, negative or critical views about the pyramids might have been handed down, and the mortuary cult of the priests was surely part of tradition. Additionally a long-standing literary tradition does not prove popularity. Even if Khufu's name survived within the literary traditions for so long, different cultural circles surely fostered different views about Khufu's character and historical deeds.[58][63] The narrations of Diodorus, for example, are credited with more trust than those of Herodotus, because Diodorus collected the tales with much more scepsis. The fact that Diodorus credits the Giza pyramid to Greek kings, might be reasoned in legends of his lifetimes and that the pyramids were demonstrably reused in late periods by Greek and Roman kings and noblemen.[23]

Modern Egyptologists and historians also call for caution about the credibility of the Arabian stories. They point out that medieval Arabs were guided by the strict Islamic belief that only one god exists, and therefore no other gods were allowed to be mentioned. As a consequence, they transferred Egyptian kings and gods into biblical prophets and kings. The Egyptian god Thoth, named Hermes by the Greeks, for example, was named after the prophet Henoch. King Khufu, as already mentioned, was named "Saurid", "Salhuk" and/or "Sarjak", and often replaced in other stories by a prophet named Šaddād bīn 'Âd. Furthermore, scholars point to several contradictions which can be found in Al-Maqrizi's book. For example, in the first chapter of the Hitat, the Copts are said to have denied any intrusion of the Amalekites in Egypt and the pyramids were erected as the tomb of Šaddād bīn 'Âd. But some chapters later, Al-Maqrizi claims that the Copts call Saurid the builder of the pyramids.[60]

Khufu in popular culture

editBecause of his fame, Khufu is the subject of several modern references, similar to kings and queens such as Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Tutankhamen. His historical figure appears in movies, novels and documentaries. In 1827, Jane C. Loudon wrote the novel The Mummy! A Tale of the 22nd Century. The story describes the citizens of the 22nd century, which became highly advanced technologically, but totally immoral. Only the mummy of Khufu can save them.[64] In 1939, Nagib Mahfuz wrote the novel Khufu's Wisdom, which is based on the stories of Papyrus Westcar.[65]

In 1997, French author Guy Rachet published the novel series Le roman des pyramides, including five volumes, of which the first two (Le temple soleil and Rêve de pierre) use Khufu and his tomb as a theme.[66] In 2004, spiritualist Page Bryant published the novel The Second Coming of the Star Gods, which deals with Khufu's alleged celestial origin.[67] The novel The Legend of The Vampire Khufu, published by Raymond Mayotte in 2010, deals with king Khufu awakening in his pyramid as a vampire.[68]

Films which deal with Khufu, or have the Great Pyramid as a subject, include Howard Hawks' Land of the Pharaohs from 1955, a fictional account of the building of the Great Pyramid of Khufu,[69] and Roland Emmerich's Stargate from 1994, in which an extraterrestrial device is found near the pyramids.

Khufu and his pyramid are the subject of pseudoscientific theories purporting that Khufu's pyramid was built with the help of extraterrestrials and that Khufu simply seized and re-used the monument,[70] ignoring archaeological evidence or even falsifying it.[71]

A near-Earth asteroid bears Khufu's name: 3362 Khufu.[72][73]

Khufu and his pyramid are referenced in several computer games such as Tomb Raider – The Last Revelation, in which the player must enter Khufu's pyramid and face the god Seth as the final boss.[74] Another example is Duck Tales 2 for the Game Boy; the player here must guide Uncle Scrooge through a trap-loaded Khufu's pyramid.[75] In the classic action role playing game Titan Quest, the Giza Plateau is a large desert region in Egypt, where the tomb of Khufu and the Great Sphinx can be found. He is also mentioned in Assassin's Creed Origins, where the player can find his tomb.[76]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Alan B. Lloyd: Herodotus, book II., p. 62.

- ^ a b Flavius Josephus, Folker Siegert: Über Die Ursprünglichkeit des Judentums (Contra Apionem), Volume 1, Flavius Josephus. From: Schriften Des Institutum Judaicum Delitzschianum, Westfalen Institutum Iudaicum Delitzschianum Münster). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 3-525-54206-2, page 85.

- ^ a b Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs. p42. Thames and Hudson, London, 2006. ISBN 978-0-500-28628-9

- ^ Malek, Jaromir, "The Old Kingdom" in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw, Oxford University Press 2000, ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7 p.88

- ^ "Khufu's 30-Year Jubilee: Newly Discovered Pieces of a Puzzle". Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c von Beckerath: Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen, Deutscher Kunstverlag (1984), ISBN 3422008322

- ^ a b Karl Richard Lepsius: Denkmaler Abtheilung II Band III Available online see p. 2, p. 39 Archived 27 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Die Sprache der Pharaonen. Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch. (= Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt. Vol. 64) 4th Edition, von Zabern, Mainz 2006, p. 111, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 pp. 52–53

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3, page 100–104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Aidan Dodson: Monarchs of the Nile. American Univ in Cairo Press, 2000, ISBN 977-424-600-4, page 29–34.

- ^ "BBC - History - Khufu". Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Rosalie F. Baker, Charles F. Baker: Ancient Egyptians: People of the Pyramids (= Oxford Profiles Series). Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0195122216, page 33.

- ^ Gundacker, Roman (2015) “The Chronology of the Third and Fourth Dynasties according to Manetho’s Aegyptiaca” in Towards a New History for the Egyptian Old Kingdom, page 114–115, provides the final vowel but disagrees with Loprieno in some details of the word’s subsequent development: where Loprieno considers the semivowels preceding the tonic /a/ to have ultimately reduced to glottal stops, Gundacker posits that /j/ assimilated to the preceding /w/, which was preserved.

- ^ Gerald Massey: The natural genesis, or, second part of A book of the beginnings: containing an attempt to recover and reconstitute the lost origins of the myths and mysteries, types and symbols, religion and language, with Egypt for the mouthpiece and Africa as the birthplace, vol. 1. Black Classic Press, 1998, ISBN 1574780107, p.224-228.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Silke Roth: Die Königsmütter des Alten Ägypten von der Frühzeit bis zum Ende der 12. Dynastie (= Ägypten und Altes Testament 46). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04368-7, pp. 354–358, 388.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Porter, Bertha and Moss, Rosalind: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings, Volume III: Memphis, Part I Abu Rawash to Abusir. 2nd edition

- ^ Grajetzki: Ancient Egyptian Queens: A Hieroglyphic Dictionary. Golden House Publications, London, 2005, ISBN 978-0-9547218-9-3

- ^ a b "Khufu's 30-Year Jubilee: Newly Discovered Pieces of a Puzzle". Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ R. Kuper and F. Forster: Khufu's 'mefat' expeditions into the Libyan Desert. In: Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 23, Autumn 2003, page 25–28 Photo of the Dachla-inscription Archived 12 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Pierre Tallet, Gregory Marouard: Wadi al-Jarf - An early pharaonic harbour on the Red Sea coast. In: Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 40, Cairo 2012, p. 40-43.

- ^ a b c d Rossella Lorenzi (12 April 2013). "Most Ancient Port, Hieroglyphic Papyri Found". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d Michael Haase: Eine Stätte für die Ewigkeit: der Pyramidenkomplex des Cheops aus baulicher, architektonischer und kulturgeschichtlicher Sicht. von Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3805331053, p. 12-13.

- ^ Sakuji Yoshimura: Sakuji Yoshimura's Excavating in Egypt for 40 Years: Waseda University Expedition 1966–2006 – Project in celebration of the 125th Anniversary of Waseda University. Waseda University, Tokyo 2006, page 134–137, 223.

- ^ a b James Henry Breasted: Ancient Records of Egypt: The first through the seventeenth dynasties. University of Illinois Press, New York 2001, ISBN 0-252-06990-0, page 83–84.

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security. Routledge, London 2001, ISBN 0-415-26011-6, pages 160–161.

- ^ "4,500-year-old harbor structures and papyrus texts unearthed in Egypt". NBC News. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Story of the Pyramid builders revealed in 4500-yr-old papyri". CatchNews.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "A 4,500 Year Old Papyrus Holds the Answer to How the Great Pyramid Was Built". interestingengineering.com. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Revealed: 4,500-year-old Papyrus that details the construction of the Great Pyramid – Mysterious Earth". Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ "Revealed: 4,500-year-old Papyrus that details the construction of the Great Pyramid". Ancient Code. 5 August 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zahi Hawass: The Khufu Statuette: Is it an Old Kingdom Sculpture? In: Paule Posener-Kriéger (Hrsg.): Mélanges Gamal Eddin Mokhtar (= Bibliothèque d'étude, vol. 97, chapter 1) Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire, Kairo 1985, ISBN 2-7247-0020-1, page 379–394.

- ^ W.M. Flinders Petrie: Abydos II., Egypt Exploration Fund, London 1903, page 3 & table XIII, obj. XIV.

- ^ a b c Abeer El-Shahawy, Farid S. Atiya: The Egyptian Museum in Cairo: A Walk Through the Alleys of Ancient Egypt. American Univ in Cairo Press, New York/Cairo 2005, ISBN 977-17-2183-6, page 49ff.

- ^ Wildung, D. Honegger, M. (ed.). About the autonomy of the arts of ancient Sudan, Nubian archaeology in the XXIst Century. Peeters Publishers. pp. 105–112.

- ^ Sakuji Yoshimura, Nozomu Kawai, Hiroyuki Kashiwagi: A Sacred Hillside at Northwest Saqqara. A Preliminary Report on the Excavations 2001–2003. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo (MDAIK). Volume 61, 2005, page 392–394; see online version with photographs Archived 21 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Sakuji Yoshimura, Nozomu Kawai, Hiroyuki Kashiwagi: A Sacred Hillside at Northwest Saqqara. A Preliminary Report on the Excavations 2001–2003. In: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo (MDAIK). Volume 61, 2005, page 392–394; see online version with photographs Archived 21 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dagmar Stockfisch: Untersuchungen zum Totenkult des ägyptischen Königs im Alten Reich. Die Dekoration der königlichen Totenkultanlagen (= Antiquitates, vol. 25.). Kovač, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-8300-0857-0.

- ^ Matthias Seidel: Die königlichen Statuengruppen, volume 1: Die Denkmäler vom Alten Reich bis zum Ende der 18. Dynastie (= Hildesheimer ägyptologische Beiträge, vol. 42.). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1996, ISBN 3-8067-8136-2, page 9–14.

- ^ Richard A. Fazzini, Robert S. Bianchi, James F. Romano, Donald B. Spanel: Ancient Egyptian Art in the Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn (NY) 1989, ISBN 0-87273-118-9.

- ^ Sylvia Schoske, Dietrich Wildung (Hrsg.): Staatliche Sammlung Ägyptischer Kunst München. (= Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie. vol. 31 = Antike Welt. vol. 26, 1995). von Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1837-5, page 43.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art, Royal Ontario Museum: Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (US) 1999, ISBN 0870999079, p.223.

- ^ John Romer: The Great Pyramid: Ancient Egypt Revisited. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 0-521-87166-2, page 414–416.

- ^ William James Hamblin: Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge, London/New York 2006, ISBN 0-415-25589-9, page 332.

- ^ Kathryn A. Bard, Steven Blake Shubert, eds.,Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0, page 1071.

- ^ Jean Leclant: Sesto Congresso internazionale di egittologia: atti, vol. 2. International Association of Egyptologists, 1993, page 186–188.

- ^ a b c d e f g Michael Haase: Eine Stätte für die Ewigkeit. Der Pyramidenkomplex des Cheops aus baulicher, architektonischer und kulturhistorischer Sicht. von Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3-8053-3105-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rainer Stadelmann: Die ägyptischen Pyramiden: Vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder. 2. überarteitete und erweiterte Auflage., von Zabern, Mainz 1991, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zahi Hawass: The Programs of the Royal Funerary Complexes of the Fourth Dynasty. In: David O'Connor, David P. Silverman: Ancient Egyptian Kingship. BRILL, Leiden 1994, ISBN 90-04-10041-5.

- ^ a b c d Peter Jánosi: Die Pyramiden: Mythos und Archäologie. Beck, Frankfurt 2004, ISBN 3-406-50831-6, page 70–72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Dietrich Wildung: Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt, Band 1: Posthume Quellen über die Könige der ersten vier Dynastien (= Münchener Ägyptologische Studien, Bd. 17). Hessling, Berlin 1969, S. 105–205.

- ^ a b Adolf Erman: Die Märchen des Papyrus Westcar I. Einleitung und Commentar. In: Mitteilungen aus den Orientalischen Sammlungen. Heft V, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin 1890.

- ^ a b Verena M. Lepper: Untersuchungen zu pWestcar. Eine philologische und literaturwissenschaftliche (Neu-)Analyse. In: Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, Band 70. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 3-447-05651-7.

- ^ a b Miriam Lichtheim: Ancient Egyptian literature: a book of readings. The Old and Middle Kingdoms, Band 1. University of California Press 2000 (2. Auflage), ISBN 0-520-02899-6

- ^ a b Friedrich Lange: Die Geschichten des Herodot, Band 1. S. 188–190.

- ^ Gunnar Sperveslage: Cheops als Heilsbringer in der Spätzeit. In: Sokar, vol. 19, 2009, page 15–21.

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt. Band 1: Posthume Quellen über die Könige der ersten vier Dynastien (= Münchener Ägyptologische Studien. Bd. 17). Hessling, Berlin 1969, page 152–192.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Siegfried Morenz: Traditionen um Cheops. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, vol. 97, Berlin 1971, ISSN 0044-216X, page 111–118.

- ^ a b c d e f Wolfgang Helck: Geschichte des Alten Ägypten (= Handbuch der Orientalistik, vol. 1.; Chapter 1: Der Nahe und der Mittlere Osten, vol 1.). BRILL, Leiden 1968, ISBN 90-04-06497-4, page 23–25 & 54–62.

- ^ a b c d Stefan Eggers: Das Pyramidenkapitel in Al-Makrizi`s "Hitat". BoD, 2003, ISBN 3833011289, p. 13-20.

- ^ a b c d Alan B. Lloyd: Herodotus, Book II: Commentary 1-98 (volume 43 of: Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain). BRILL, Leiden 1993, ISBN 9004077375, page 62 - 63.

- ^ William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (= The Loeb classical Library. Bd. 350). Harvard University Press u. a., Cambridge MA u. a. 1997, ISBN 0-674-99385-3, page 46 & 47.

- ^ a b Erhart Graefe: Die gute Reputation des Königs "Snofru". In: Studies in Egyptology Presented to Miriam Lichtheim, vol. 1. page 257–263.

- ^ Jane C. Loudon: The Mummy! A Tale of the 22nd Century. Henry Colburn, London 1827.

- ^ Najīb Maḥfūẓ (Author), Raymond T. Stock (Translator): Khufu's Wisdom, 2003.

- ^ Guy Rachet: Le roman des pyramides. Éd. du Rocher, Paris 1997.

- ^ "The Second Coming of the Star Gods". GoodReads.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Raymond Mayotte: The Legend of The Vampire Khufu. CreateSpace, Massachusetts 2010, ISBN 1-4515-1934-6.

- ^ Philip C. DiMare: Movies in American History. p. 891

- ^ cf. Erich von Däniken: Erinnerungen an die Zukunft (memories to the future). page 118.

- ^ Ingo Kugenbuch: Warum sich der Löffel biegt und die Madonna weint. page 139–142.

- ^ 3362 Khufu in the internet-database of Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) (English).

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel: Dictionary of minor planet names. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg 2003 (5th edition), ISBN 3-540-00238-3, page 280.

- ^ Information about Khufu's pyramid in Tomb Raider IV Archived 21 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine (English).

- ^ Information about Khufu's pyramid in Duck Tales 2 Archived 21 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine (English).

- ^ "Tomb of Khufu". IGN. 11 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

External links

edit- "Travertine fragment of a small seated statue of Khufu, on display in the Boston museum of fine arts".

- "Zahi Hawass: Khufu – Builder of the Great Pyramid".

- "Information about Khufu and his pyramid".

- "An early pharaonic harbour on the Red Sea coast".

- "The Harbor of Khufu on the Red Sea Coast at Wadi al-Jarf".

- "La découverte des papyrus de Chéops sur le port antique du ouadi el-Jarf".