In Japanese, kokuji (国字, "national characters") or wasei kanji (和製漢字, "Japanese-made kanji") are kanji created in Japan rather than borrowed from China. Like most Chinese characters, they are primarily formed by combining existing characters - though using combinations that are not used in Chinese.

Since kokuji are generally devised for existing native words, they usually only have native kun readings. However, they occasionally also have a Chinese on reading derived from a related kanji, such as 働 (dō, 'work'), which takes its on pronunciation from 動 (dō, 'move'). In rare cases, a kokuji may only have an on reading, such as 腺 (sen, 'gland'), which was derived from 泉 (sen, 'spring, fountain') for use in medical terminology.

The majority of kokuji are semantic compounds, meaning that they are composed of two (or more) characters with relevant meanings. For example, 働 ('work') is composed of 亻 ('person' radical) plus 動 ('move'). This is in contrast to Chinese kanji, which are overwhelmingly phono-semantic compounds. This is because the phonetic element of phono-semantic kanji is always based on the on reading, which most kokuji don't have, leaving semantic compounding as the only alternative. Other examples include 榊 'sakaki tree', formed from 木 'tree' and 神 'deity' (literally 'divine tree'), and 辻 'crossroads' formed from 辶 'road' and 十 'cross'.

Kokuji are especially common for describing species of flora and fauna including a very large number of fish such as 鰯 (sardine), 鱈 (codfish), 鮴 (seaperch), and 鱚 (sillago), and trees such as 樫 (evergreen oak), 椙 (Japanese cedar), 椛 (birch, maple) and 柾 (spindle tree).[1]

Term

editThe term kokuji in Japanese can refer to any character created outside of China, including Korean gukja (國字, 국자) and Vietnamese chữ Nôm. Wasei kanji refers specifically to kanji invented in Japan.

History

editHistorically, some kokuji date back to very early Japanese writing, being found in the Man'yōshū, for example—鰯 iwashi "sardine" dates to the Nara period (8th century)—while they have continued to be created as late as the late 19th century, when a number of characters were coined in the Meiji era for new scientific concepts. For example, some characters were produced as regular compounds for some (but not all) SI units, such as 粁 (米 "meter" + 千 "thousand, kilo-") for kilometer, 竏 (立 "liter" + 千 "thousand, kilo-") for kiloliter, and 瓩 (瓦 "gram" + "thousand, kilo-") for kilogram. However, SI units in Japanese today are almost exclusively written using rōmaji or katakana such as キロメートル or ㌖ for km, キロリットル for kl, and キログラム or ㌕ for kg.[2]

In Japan, the kokuji category is strictly defined as characters whose earliest appearance is in Japan.[3] If a character appears earlier in the Chinese literature, it is not considered a kokuji even if the character was independently coined in Japan and unrelated to the Chinese character (meaning "not borrowed from Chinese"). In other words, kokuji are not simply characters that were made in Japan, but characters that were first made in Japan. An illustrative example is ankō (鮟鱇, monkfish). This spelling was created in Edo period Japan from the ateji (phonetic kanji spelling) 安康 for the existing word ankō by adding the 魚 radical to each character—the characters were "made in Japan". However, 鮟 is not considered kokuji, as it is found in ancient Chinese texts as a corruption of 鰋 (魚匽). 鱇 is considered kokuji, as it has not been found in any earlier Chinese text. Casual listings may be more inclusive, including characters such as 鮟.[note 1] Another example is 搾, which is sometimes not considered kokuji due to its earlier presence as a corruption of Chinese 榨.

Examples

editThere are hundreds of kokuji in existence.[4] Many are rarely used, but a number have become commonly used components of the written Japanese language. These include the following:

Jōyō kanji has about nine kokuji; there is some dispute over classification, but the following are generally included:

- 働 どう dō, はたら(く) hatara(ku) "work", the most commonly used kokuji, used in the fundamental verb hatara(ku) (働く, "work"), included in elementary texts and on the Proficiency Test N5.

- 込 こ(む) ko(mu), used in the fundamental verb komu (込む, "to be crowded")

- 匂 にお(う) nio(u), used in common verb niou (匂う, "to smell, to be fragrant")

- 畑 はたけ hatake "field of crops"

- 腺 せん sen, "gland"

- 峠 とうげ tōge "mountain pass"

- 枠 わく waku, "frame"

- 塀 へい hei, "wall"

- 搾 しぼ(る) shibo(ru), "to squeeze" (disputed; see above);

Jinmeiyō kanji:

- 榊 さかき sakaki "tree, genus Cleyera"

- 辻 つじ tsuji "crossroads, street"

- 匁 もんめ monme (unit of weight)

Hyōgaiji kanji:

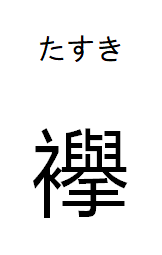

- 躾 しつけ shitsuke "training, rearing (an animal, a child)"

Some of these characters (for example, 腺, "gland")[5] have been introduced to China; additionally, Standard Mandarin readings are assigned to some kokuji used in Japanese toponymy, for example by the Guobiao standard GB/T 17693.10.[6] In some cases, the Chinese reading is the inferred Chinese reading, interpreting the character as a phono-semantic compound (as in how on readings are sometimes assigned to these characters in Chinese), while, in other cases (such as 働), the Japanese on reading is borrowed (in general this differs from the modern Chinese pronunciation of this phonetic). Similar coinages occurred to a more limited extent in Korea and Vietnam.

See also

edit- Gukja, Chinese characters created in Korea.

- Chữ Nôm, Chinese characters created in Vietnam.

- Sawndip, Chinese characters created by the Zhuang people.

- Wasei-kango, words in the Japanese language composed of Chinese morphemes but invented in Japan.

- Ryakuji, colloquial simplifications of kanji in Japan.

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ Koichi (2012-08-21). "Kokuji: "Made In Japan," Kanji Edition". Tofugu. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- ^ "A list of kokuji (国字)". www.sljfaq.org. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- ^ Buck, James H. (1969). "Some Observations on kokuji". The Journal-Newsletter of the Association of Teachers of Japanese. 6 (2): 45–49. doi:10.2307/488823. ISSN 0004-5810. JSTOR 488823. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ "Kokuji list", SLJ FAQ, archived from the original on May 14, 2011, retrieved January 10, 2011.

- ^ Buck, James H. (October 15, 1969) "Some Observations on kokuji" in The Journal-Newsletter of the Association of Teachers of Japanese, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 45–9.

- ^ Zapryagaev, Alexander (2022-08-12). "Proposal to Correct Several kMandarin Readings for Japanese-made Kanji" (PDF). UTC L2/22-186.