Hieronymus Bosch (/haɪˈrɒnɪməs bɒʃ, bɔːʃ, bɔːs/;[1][2][3][4] Dutch: [ɦijeːˈroːnimʏz ˈbɔs] ;[a] born Jheronimus van Aken[5] [jeːˈroːnimʏs fɑn ˈaːkə(n)];[b] c. 1450 – 9 August 1516) was a Dutch painter from Brabant. He is one of the most notable representatives of the Early Netherlandish painting school. His work, generally oil on oak wood, mainly contains fantastic illustrations of religious concepts and narratives.[6] Within his lifetime, his work was collected in the Netherlands, Austria, and Spain, and widely copied, especially his macabre and nightmarish depictions of hell.

Hieronymus Bosch | |

|---|---|

Jheronimus Bosch | |

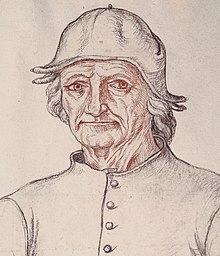

Portrait of Hieronymus Bosch from the Recueil d'Arras | |

| Born | Jheronimus van Aken c. 1450 |

| Died | Buried on 9 August 1516 (aged 65–66) 's-Hertogenbosch, Duchy of Brabant, Habsburg Netherlands |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | The Garden of Earthly Delights The Temptation of St. Anthony |

| Movement | Early Netherlandish, Renaissance |

| Signature | |

Little is known of Bosch's life, though there are some records. He spent most of it in the town of 's-Hertogenbosch, where he was born in his grandfather's house. The roots of his forefathers are in Nijmegen and Aachen (which is visible in his surname: Van Aken). His pessimistic fantastical style cast a wide influence on northern art of the 16th century, with Pieter Bruegel the Elder being his best-known follower. Today, Bosch is seen as a highly individualistic painter with deep insight into humanity's desires and deepest fears. Attribution has been especially difficult; today only about 25 paintings are confidently given to his hand[7] along with eight drawings. About another half-dozen paintings are confidently attributed to his workshop. His most acclaimed works consist of three triptych altarpieces, including The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Life

editHieronymus Bosch's first name was originally Jheronimus (or Joen,[8] respectively the Latin and Middle Dutch form of the name "Jerome"), and he signed a number of his paintings as Jheronimus Bosch.[9]

His surname Bosch derives from his birthplace, 's-Hertogenbosch ('Duke's forest'), which is commonly called "Den Bosch" ('the forest').[10]

Little is known of Bosch's life or training. He left behind no letters or diaries, and what has been identified has been taken from brief references to him in the municipal records of 's-Hertogenbosch, and in the account books of the local order of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady. Nothing is known of his personality or his thoughts on the meaning of his art. Bosch's date of birth has not been determined with certainty. It is estimated at c. 1450 on the basis of a hand-drawn portrait (which may be a self-portrait) made shortly before his death in 1516. The drawing shows the artist at an advanced age, probably in his late sixties.[11]

Bosch lived all his life in and near 's-Hertogenbosch, in the Duchy of Brabant. His grandfather Jan van Aken (died 1454) was a painter and is first mentioned in the records in 1430. Jan had five sons, four of whom were also painters. Bosch's father, Anthonius van Aken (died c. 1478), acted as artistic adviser to the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady.[12] It is generally assumed that either Bosch's father or one of his uncles taught the artist to paint, but none of their works survive.[13] Bosch first appears in the municipal record on 5 April 1474, when he is named along with two brothers and a sister.[14]

's-Hertogenbosch was a flourishing city in 15th-century Brabant, in the south of the present-day Netherlands, at the time part of the Burgundian Netherlands, and during its[clarification needed] lifetime passing through marriage to the Habsburgs.[citation needed] In 1463, four thousand houses in the town were destroyed by a catastrophic fire, which the then (approximately) thirteen-year-old Bosch presumably witnessed. He became a popular painter in his lifetime and often received commissions from abroad.[citation needed] In 1486/7 he joined the highly respected Brotherhood of Our Lady, a devotional confraternity of some forty influential citizens of 's-Hertogenbosch, and seven thousand 'outer-members' from around Europe.[14]

Sometime between 1479 and 1481, Bosch married Aleid Goyaerts van den Meervenne, who was a few years his senior. The couple moved to the nearby town of Oirschot, where Aleid Goyaerts van den Meervenne had inherited a house and land from her wealthy family.[15] An entry in the accounts of the Brotherhood of Our Lady records Bosch's death in 1516. A funeral mass served in his memory was held in the church of Saint John on 9 August of that year.[16]

Works

editBosch produced at least sixteen triptychs: of them, eight survive fully intact with another five surviving in fragments.[17] Bosch's works are generally organised into three periods of his life dealing with the early works (c. 1470–1485), the middle period (c. 1485–1500), and the late period (c. 1500 until his death). According to Stefan Fischer, thirteen of Bosch's surviving paintings were completed in the late period, with seven attributed to his middle period.[18] Bosch's early period is studied in terms of his workshop activity and possibly some of his drawings. Indeed, he taught pupils in the workshop, who were influenced by him. The recent dendrochronological investigation of the oak panels by the scientists at the Bosch Research and Conservation Project[19] led to a more precise dating of the majority of Bosch's paintings.[20]

Bosch sometimes painted in a comparatively sketchy manner, contrasting with the traditional Early Netherlandish style of painting in which the smooth surface—achieved by the application of multiple transparent glazes—conceals the brushwork.[citation needed] His paintings with their rough surfaces, so-called impasto painting, differed from the tradition of the great Netherlandish painters of the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries, who wished to hide the work done and thus suggest their paintings as more nearly divine creations.[21]

Bosch did not date his paintings, but—unusually for the time—seems to have signed several of them, although some signatures purporting to be his are certainly not. About twenty-five paintings remain today that can be attributed to him. In the late 16th century, Philip II of Spain acquired many of Bosch's paintings.[22] As a result, the Prado Museum in Madrid now owns the Adoration of the Magi, The Garden of Earthly Delights, the tabletop painting of The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things and The Haywain Triptych.[14]

Painting materials

editBosch painted his works mostly on oak panels using oil as a medium. Bosch's palette was rather limited and contained the usual pigments of his time.[23] He mostly used azurite for blue skies and distant landscapes, green copper-based glazes and paints consisting of malachite or verdigris for foliage and foreground landscapes, and lead-tin-yellow, ochres and red lake (carmine or madder lake) for his figures.[24]

The Garden of Earthly Delights

editOne of his most famous triptychs is The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1495–1505) whose outer panels are intended to bracket the main central panel between the Garden of Eden depicted on the left panel and the Last Judgment depicted on the right panel. It is attributed by Fischer as a transition painting rendered by Bosch from between his middle period and his late period. In the left hand panel God presents Eve to Adam; innovatively God is given a youthful appearance. The figures are set in a landscape populated by exotic animals and unusual semi-organic hut-shaped forms. The central panel is a broad panorama teeming with nude figures engaged in innocent, self-absorbed joy, as well as fantastical compound animals, oversized fruit, and hybrid stone formations.[25]

The right panel presents a hellscape; a world in which humankind has succumbed to the temptations of evil and is reaping eternal damnation. Set at night, the panel features cold colours, tortured figures and frozen waterways. The nakedness of the human figures has lost any eroticism suggested in the central panel,[26] as large explosions in the background throw light through the city gate and spill onto the water in the panel's midground.[27]

Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony

editTriptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony is one of the most famous Bosch's works along with The Garden of Earthly Delights. It shows Saint Anthony being tempted or assailed in the desert by demons, whose temptations he resisted; the Temptation of St Anthony (or Trial...) is the more common name of the subject. But strictly there are at least two different episodes deriving from Athanasius's Life of St. Anthony and later versions of the life that may be represented, though all usually have this name.

The most common is the temptation, by seductive women and other demonic forms, but the Martin Schongauer composition (copied by Michelangelo) probably shows a later episode where St Anthony, normally flown about the desert supported by angels, was ambushed and attacked in mid-air by devils. Anasthasius describes another episode where the saint was attacked on the ground.

With copied content from Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony; see that page for attribution.

Interpretation

editIn the 20th century, when changing artistic tastes made artists like Bosch more palatable to the European imagination, it was sometimes argued that Bosch's art was inspired by heretical points of view (e.g., the ideas of the Cathars and/or putative Adamites or Brethren of the Free Spirit)[28] as well as by obscure hermetic practices. Again, since Erasmus had been educated at one of the houses of the Brethren of the Common Life in 's-Hertogenbosch, and the town was religiously progressive, some writers have found it unsurprising that strong parallels exist between the caustic writing of Erasmus and the often bold painting of Bosch.[29]

Others, following a strain of Bosch-interpretation datable already to the 16th century, continued to think his work was created merely to titillate and amuse, much like the "grotteschi" of the Italian Renaissance. While the art of the older masters was based in the physical world of everyday experience, Bosch confronts his viewer with, in the words of the art historian Walter Gibson, "a world of dreams [and] nightmares in which forms seem to flicker and change before our eyes". In one of the first known accounts of Bosch's paintings, in 1560 the Spaniard Felipe de Guevara wrote that Bosch was regarded merely as "the inventor of monsters and chimeras". In the early 17th century, the artist-biographer Karel van Mander described Bosch's work as comprising "wondrous and strange fantasies"; however, he concluded that the paintings are "often less pleasant than gruesome to look at".[30]

In recent decades, scholars have come to view Bosch's vision as less fantastic, and accepted that his art reflects the orthodox religious belief systems of his age.[31] His depictions of sinful humanity and his conceptions of Heaven and Hell are now seen as consistent with those of late medieval didactic literature and sermons. Most writers attach a more profound significance to his paintings than had previously been supposed, and attempt to interpret them in terms of a late medieval morality. It is generally accepted that Bosch's art was created to teach specific moral and spiritual truths in the manner of other Northern Renaissance figures, such as the poet Robert Henryson, and that the images rendered have precise and premeditated significance. According to Dirk Bax, Bosch's paintings often represent visual translations of verbal metaphors and puns drawn from both biblical and folkloric sources.[32]

Latterly art historians have added a further dimension to the subject of ambiguity in Bosch's work, emphasising ironic tendencies, for example in The Garden of Earthly Delights, both in the central panel (delights),[33] and the right panel (hell).[34] They theorise that the irony offers the option of detachment, both from the real world and from the painted fantasy world, thus appealing to both conservative and progressive viewers.[citation needed] According to Joseph Koerner, some of the cryptic qualities of the artist's work are due to his special focus on social, political, and spiritual enemies, whose symbolism is, by nature, disguised because it is intended to conceal the artist from criticism and harm.[35]

A 2012 study on Bosch's paintings alleges that they actually conceal a strong nationalist consciousness, censuring the foreign imperial government of the Burgundian Netherlands, especially Maximilian Habsburg.[36] By systematically superimposing images and concepts, the study asserts that Bosch also made his expiatory self-punishment, for he was accepting well-paid commissions from the Habsburgs and their deputies, and therefore betraying the memory of Charles the Bold.[37]

Debates on attribution

editThe exact number of Bosch's surviving works has been a subject of considerable debate.[38] His signature can be seen on only seven of his surviving paintings, and there is uncertainty whether all the paintings once ascribed to him were actually from his hand. It is known that from the early 16th century onward, numerous copies and variations of his paintings began to circulate. In addition, his style was highly influential, and was widely imitated by his numerous followers.[39]

Over the years, scholars have attributed to him fewer and fewer of the works once thought to be his. This is partly a result of technological advances such as infrared reflectography, which enable researchers to examine a painting's underdrawing.[40] Art historians of the early and mid-20th century, such as Tolnay[41] and Baldass,[42] identified between thirty and fifty paintings that they believed to be by Bosch's hand.[43] A later monograph by Gerd Unverfehrt (1980) attributed twenty-five paintings and 14 drawings to him.[43]

In early 2016, The Temptation of St. Anthony, a small panel in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, long attributed to the workshop of Hieronymus Bosch, was credited to the painter himself after intensive forensic study by the Bosch Research and Conservation Project.[7][44][45] The BRCP has also questioned whether two well-known paintings traditionally accepted to be by Bosch, The Seven Deadly Sins in the Prado and Christ Carrying the Cross in the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent should instead be credited to the artist's workshop rather than to the painter's own hand.[46]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ In isolation, Hieronymus is pronounced [ɦijeːˈroːnimʏs] .

- ^ In isolation, van is pronounced [vɑn] .

References

edit- ^ "Bosch, Hieronymus". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Bosch". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Bosch". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Bosch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Dijck (2000): pp. 43–44. His birth is undocumented. However, the Dutch historian G.C.M. van Dijck points out that the vast majority of contemporary archival entries state his name as being Jheronimus van Aken. Variants on his name are Jeronimus van Aken (Dijck (2000): pp. 173, 186), Jheronimus anthonissen van aken (Marijnissen ([1987]): p. 12), Jeronimus Van aeken (Marijnissen ([1987]): p. 13), Joen (Dijck (2000): pp. 170–171, 174–177), and Jeroen (Dijck (2000): pp. 170, 174).

- ^ Catherine B. Scallen, The Art of the Northern Renaissance (Chantilly: The Teaching Company, 2007) Lecture 26

- ^ a b Siegal, Nina (1 February 2016). "Hieronymus Bosch Credited With Work in Kansas City Museum". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Dijck (2000): pp. 43–44. A variant on his Middle Dutch name is "Jeroen". Van Dijck points out that in all contemporary sources the name "Jeroen" is used twice, while the name "Joen" is used nine times, making "Joen" to be his probable nickname.

- ^ Signed works by Bosch include The Adoration of the Magi, Saint Christopher Carrying the Christ Child, St. John the Evangelist on Patmos, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, The Hermit Saints Triptych, and The Crucifixion of St Julia.

- ^ Rowland, Ingrid D. (18 August 2016). "The Mystery of Hieronymus Bosch". The New York Review. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Gibson, 15–16

- ^ Gibson, 15, 17

- ^ Gibson, 19

- ^ a b c "Bosch, Hieronymus – The Collection". Museo Nacional del Prado. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Valery, Paul. The Phase of Doubt, A Critical Reflection.

- ^ Gibson, 18

- ^ Jacobs, 1010

- ^ Stefan Fischer. Bosch: The Complete Works.

- ^ Bosch Research and Conservation Project, 2016

- ^ Luuk Hoogstede; Ron Spronk; Matthijs Ilsink; Robert G. Erdmann; Jos Koldeweij; Rik Klein Gotink (2016). Hieronymus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman: Technical Studies. Yale University Press.

- ^ "Hieronymus Bosch: The Delights of Hell". Films Media Group. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014.

- ^ Checa Cremades, Fernando. "Colección de Felipe II – Museo Nacional del Prado". Museo del Prado (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Hoogstede et al. (2016)

- ^ "Hieronymus Bosch: General Resources". ColourLex. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Fraenger, 10

- ^ Belting, 38

- ^ Gibson, 92

- ^ The Millennium of Hieronymus Bosch. Outlines of a New Interpretation. Wilhelm Fraenger, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1951

- ^ The Secret Life of Paintings. Richard Foster & Pamela Tudor-Craig ISBN 0-85115-439-5

- ^ Gibson, 9

- ^ Bosing, Walter (1987). Hieronymus Bosch. Taschen.

- ^ Bax, 1949.

- ^ Pokorny (2010), 23, 25, 31.

- ^ Boulboullé (2008), 68, 70–72, 75–76.

- ^ Koerner (2016), 179–222.

- ^ Oliveira, Paulo Martins (2012). Jheronimus Bosch: O relojoeiro dos símbolos. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. pp. 199–218. ISBN 978-1-4791-6765-4..

- ^ Oliveira, Paulo Martins (2013). "Bosch, the surdo canis". Dokumen.tips. Archived from the original on 20 November 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Büttner, Nils (15 June 2016). Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-614-8.

- ^ Gibson, 163

- ^ Finaldi, Gabriele/ Garrido, Carmen "El trazo oculto. Dibujos subyacentes en pinturas de los siglos XV y XVI" (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid 2006)

- ^ Tolnay, Charles de "Hieronymus Bosch" (Methuen & Co, London 1966)

- ^ Baldass, Ludwig v. "Hieronimus Bosch" ( Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1960)

- ^ a b Muller, Sheila D. (1997). Dutch Art: an Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Pub. p. 47. ISBN 0-8153-0065-4.

- ^ Russell, Anna (1 February 2016). "Kansas City Museum Painting Deemed an Authentic Bosch". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Hoedel, Cindy (1 February 2016). "Rare Painting by Dutch Master Hieronymous Bosch Has Been in Storage at Nelson-Atkins". The Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Neuendorf, Henri (2 November 2015). "Scientists Question Attribution of Two Hieronymus Bosch Masterpieces". Artnet. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

Bibliography

edit- Bax, Dirk. Ontcijfering van Jeroen Bosch. Den Haag: Staats-drukkerij-en Uitgeverijbedrijf, 1949.

- Boulboullé, Guido. "Groteske Angst. Die Höllenphantasien des Hieronymus Bosch". In: Auffarth, Christoph and Kerth, Sonja (Eds): Glaubensstreit und Gelächter: Reformation und Lachkultur im Mittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2008. 55–78.

- Dijck, Godfried Christiaan Maria van. Op zoek naar Jheronimus van Aken alias Bosch. De feiten. Familie, vrienden en opdrachtgevers. Zaltbommel: Europese Bibliotheek, 2001. ISBN 90-288-2687-4

- Fischer, Stefan. Hieronymus Bosch. The Complete Works. Köln: Taschen, 2016 ISBN 978-3836526296

- Fraenger, Wilhelm. Hieronymus Bosch. Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1975.

- Le royaume millénaire de Jérôme Bosch (French transl. by Roger Lewinter, Paris: Ivrea, 1993).

- Gibson, Walter. Hieronymus Bosch. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1973. ISBN 0-500-20134-X

- Jacobs, Lynn. "The Triptychs of Hieronymus Bosch". The Sixteenth Century Journal, Volume 31, No. 4, 2000. 1009–1041

- Koerner, Joseph Leo. Bosch and Bruegel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life. Princeton University Press, 2016. ISBN 9780691172286

- Koldeweij, Jos & Vermet, Bernard & van Kooij, Barbera. Hieronymus Bosch. New Insights Into His Life and Work. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2001. ISBN 90-5662-214-5

- Malizia, Enrico. Hieronymus Bosch. Insigne pittore nel crepuscolo del medio evo. Stregoneria, magia, alchimia, simbolismo. Roma: Youcanprint Ed., 2015. ISBN 978-88-91171-74-0

- Marijnissen, Roger. Hiëronymus Bosch. Het volledige oeuvre. Haarlem: Gottmer/Brecht, 1987. ISBN 90-230-0651-8

- Pokorny, Erwin. "Hieronymus Bosch und das Paradies der Wollust". In: Frühneuzeit-Info, Jg. 21, Heft 1+2 ("Sonderband: Die Sieben Todsünden in der Frühen Neuzeit"), 2010. 22–34.

- Strickland, Debra Higgs. The Epiphany of Hieronymys Bosch. Imagining Antichrist and Others from the Middle Ages to the Reformation (Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History), Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2016, ISBN 978-1-909400-55-9

Further reading

edit- Ilsink, Matthijs; Koldeweij, Jos (2016). Hieronymus Bosch: Painter and Draughtsman – Catalogue raisonné. Yale University Press. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-300-22014-8.

External links

edit- Jheronimus Bosch Art Center

- Hieronymus Bosch at Ibiblio

- "Hieronymus Bosch, Tempter and Moralist" Analysis by Larry Silver.

- Hieronymus Bosch – The complete works Archived 20 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine, 188 works by Bosch

- Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP)

- Hieronymus Bosch, General Resources, ColourLex

- Bosch, the Fifth Centenary Exhibition: At the Prado

- Works at Open Library

- K. Katelyn Hobbs, "Ecce Homo by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch (cat. 352)"[permanent dead link] in The John G. Johnson Collection: A History and Selected Works, a Philadelphia Museum of Art free digital publication.