The Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos are located in the Santa Cruz department in eastern Bolivia. Six of these former missions (all now secular municipalities) collectively were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1990. Distinguished by a unique fusion of European and Amerindian cultural influences, the missions were founded as reductions or reducciones de indios by Jesuits in the 17th and 18th centuries to convert local tribes to Christianity.

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Church in Concepción | |

| Location | Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia |

| Includes | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv), (v) |

| Reference | 529 |

| Inscription | 1990 (14th Session) |

| Coordinates | 16°46′15″S 61°27′15″W / 16.770846°S 61.454265°W |

The interior region bordering Spanish and Portuguese territories in South America was largely unexplored at the end of the 17th century. Dispatched by the Spanish Crown, Jesuits explored and founded eleven settlements in 76 years in the remote Chiquitania – then known as Chiquitos – on the frontier of Spanish America. They built churches (templos) in a unique and distinct style that combined elements of native and European architecture. The indigenous inhabitants of the missions were taught European music as a means of conversion. The missions were self-sufficient, with thriving economies, and virtually autonomous from the Spanish crown.

After the expulsion of the Jesuit order from Spanish territories in 1767, most Jesuit reductions in South America were abandoned and fell into ruins. The former Jesuit missions of Chiquitos are unique because these settlements and their associated culture have survived largely intact.

A large restoration project of the missionary churches began with the arrival of the former Swiss Jesuit and architect Hans Roth in 1972. Since 1990, these former Jesuit missions have experienced some measure of popularity, and have become a tourist destination. A popular biennial international musical festival put on by the nonprofit organization Asociación Pro Arte y Cultura[1] along with other cultural activities within the mission towns, contribute to the popularity of these settlements.

Location

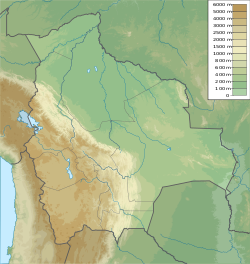

editThe six World Heritage Site settlements are located in the hot and semiarid lowlands of the Santa Cruz Department of eastern Bolivia. They lie in an area near the Gran Chaco, east and northeast of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, between the Paraguay and Guapay rivers.

The westernmost missions are San Xavier (also known as San Javier) and Concepción, located in the province of Ñuflo de Chávez between the San Julián and Urugayito rivers. Santa Ana de Velasco, San Miguel de Velasco, and San Rafael de Velasco are located to the east, in José Miguel de Velasco province, near the Brazilian border. San José de Chiquitos is located in Chiquitos province, about 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of San Rafael.

Three other former Jesuit missions – San Juan Bautista (now in ruins), Santo Corazón and Santiago de Chiquitos – which have not been named UNESCO heritage sites – lie east of San José de Chiquitos not far from the town of Roboré. The capital of José Miguel de Velasco Province, San Ignacio de Velasco was founded as a Jesuit mission but is also not a World Heritage Site as the current church is a reconstruction, not a restoration.[2]

The name “Chiquitos”

editÑuflo de Chavés, a 16th-century Spanish conquistador and founder of Santa Cruz "la Vieja", introduced the name Chiquitos, or little ones. It referred to the small doors of the straw houses in which the indigenous population lived.[nb 1][3] Chiquitos has since been used incorrectly both to denote people of the largest ethnic group in the area (correctly known as Chiquitano), and collectively to denote the more than 40 ethnic groups with different languages and cultures living in the region known as the [Gran] Chiquitania.[4][5] Properly, “Chiquitos” refers only to either a modern-day department of Bolivia, or the former region of Upper Peru (now Bolivia) that once encompassed all of the Chiquitania and parts of Mojos (or Moxos) and the Gran Chaco.

The current provincial division of Santa Cruz department does not follow the Jesuits’ concept of a missionary area. The Chiquitania lies within five modern provinces: Ángel Sandoval, Germán Busch, José Miguel de Velasco, Ñuflo de Chávez and Chiquitos province.[4][6][7]

History

editIn the 16th century, priests of different religious orders set out to evangelize the Americas, bringing Christianity to indigenous communities. Two of these missionary orders were the Franciscans and the Jesuits, both of which eventually arrived in the frontier town of Santa Cruz de la Sierra and then in the Chiquitania. The missionaries employed the strategy of gathering the often nomadic indigenous populations in larger communities called reductions in order to more effectively Christianize them. This policy sprang from the colonial legal view of the “Indian” as a minor, who had to be protected and guided by European missionaries so as not to succumb to sin. Reductions, whether created by secular or religious authorities, generally were construed as instruments to force the natives to adopt European culture and lifestyles and the Christian religion. The Jesuits were unique in attempting to create a theocratic "state within a state" in which the native peoples in the reductions, guided by the Jesuits, would remain autonomous and isolated from Spanish colonists and Spanish rule.[8]

Arrival in the Viceroyalty of Peru

editWith the permission of King Philip II of Spain a group of Jesuits traveled to the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1568, some 30 years after the arrival of the Franciscans, Dominicans, Augustinians and Mercedarians. The Jesuits established themselves in Lima in 1569 before moving east toward Paraguay; in 1572 they reached the Audience of Charcas in modern-day Bolivia. Because they were not allowed to establish settlements on the frontier they built chapter houses, churches and schools in pre-existing settlements, such as La Paz, Potosí and La Plata (present day Sucre).[7][9]

In 1587 the first Jesuits, Fr. Diego Samaniego and Fr. Diego Martínez, arrived in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, located just south of where the future mission of San José de Chiquitos would be established. In 1592 the settlement had to be moved 250 kilometres (160 mi) west because of conflicts with natives, although the remains of the original town exist in the Santa Cruz la Vieja archaeological site. The Jesuits did not start missions in the valleys northeast of the cordillera until the 17th century. The two central areas for their activities were Moxos, situated in the department of Beni, and the Chiquitania (then simply Chiquitos) in the department of Santa Cruz de la Sierra.[9] In 1682, Fr. Cipriano Barace founded the first of the Jesuit reductions in Moxos, located at Loreto.

The Jesuits in the Chiquitania

editWhile the mission towns in Paraguay flourished, the evangelization of the Eastern Bolivian Guarani (Chiriguanos) proved difficult. With encouragement from Agustín Gutiérrez de Arce, the governor of Santa Cruz, the Jesuits focused their efforts on the Chiquitania, where the Christian doctrine was more readily accepted.[4] Between 1691 and 1760 eleven missions were founded in the area;[2] however, fires, floods, plagues, famines and conflict with hostile tribes or slave traders caused many missions to be re-established or rebuilt.[3] The Chiquitos missions suffered from periodic epidemics of European diseases killing up to 11 percent of the population in a single episode. However, the epidemics were not as severe as they were among the Paraguayan Guarani to the east, mainly because of their remote locations and the lack of transportation infrastructure.[10][11]

The first Jesuit reduction in the Chiquitania was the mission of San Francisco Xavier, founded in 1691 by the Jesuit priest Fr. José de Arce. In September 1691, de Arce and Br. Antonio de Rivas intended to meet seven other Jesuits at the Paraguay River to establish a connection between Paraguay and Chiquitos. However, the beginning of the rainy season brought bad weather, and Arce and his companion only got as far as the first native village. The local Piñoca tribe, who were suffering from a plague, begged Arce and Rivas to stay and promised to build a house and a church for the Jesuits, which were finished by the end of year. The mission was later moved a number of times until 1708 when it was established in its present location.[4]

Ten more missions were founded in the Chiquitania by the Jesuits in three periods: the 1690s, the 1720s, and after 1748. In the 1690s, five missions were established: San Rafael de Velasco (1696), San José de Chiquitos (1698), Concepción (1699) and San Juan Bautista (1699). San Juan Bautista is not part of the World Heritage Site, and only the ruins of a stone tower survive near the present village of San Juan de Taperas.

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) caused a shortage of missionaries and instability in the reductions, so no new missions were built during this period. By 1718 San Rafael was the largest of the Chiquitos missions, and with 2,615 inhabitants[10] could not sustain a growing population. In 1721 the Jesuits Fr. Felipe Suárez and Fr. Francisco Hervás established a split-off of the San Rafael mission, the mission of San Miguel de Velasco. To the south, San Ignacio de Zamucos was founded in 1724 but abandoned in 1745; today nothing remains of the mission.[4][11]

A third period of mission foundations began in 1748 with the establishment of San Ignacio de Velasco, which was not declared a part of the World Heritage Site. The church is nonetheless a largely faithful 20th-century reconstruction – as opposed to renovation (a key criterion for inclusion in the World Heritage Site group) – of the second Jesuit templo built in 1761. In 1754 the Jesuits founded the mission of Santiago de Chiquitos. This church also is a reconstruction, dating from the early 20th century and likewise is not part of the World Heritage Site group. In 1755 the mission of Santa Ana de Velasco was founded by the Jesuit Julian Knogler; it is the most authentic of the six World Heritage Site missions dating from the colonial period. The last mission in the Chiquitania to be established was founded by the Jesuits Fr. Antonio Gaspar and Fr. José Chueca as Santo Corazón in 1760. The local Mbaya peoples were hostile to the mission[12] and nothing of the original settlement remains in the modern village.[3][9]

The Jesuits in the Chiquitania had a secondary objective, which was to secure a more direct route to Asunción than the road then being used via Tucumán and Tarija to link the Chiquitania with the Jesuit missions in Paraguay.[13] The missionaries in Chiquitos founded their settlements increasingly further east, towards the Paraguay River, while those south of Asunción moved closer to the Paraguay River by establishing their missions increasingly farther north, thereby avoiding the impassable Chaco region. Although Ñuflo de Chávez had attempted a route through the Chaco on an expedition as early as 1564, subsequent Jesuit explorations from Chiquitos (e.g. in 1690, 1702, 1703, and 1705) were unsuccessful. The Jesuits were stopped by the hostile Payaguá and Mbayá (Guaycuruan-speaking tribes), and by the impenetrable swamps of Jarayes. In 1715, de Arce, the co-founder of the first mission in San Xavier, set out from Asunción on the Paraguay River with the Flemish priest Fr. Bartolomé Blende. Payaguá warriors killed Blende during the journey, but de Arce struggled on to reach San Rafael de Velasco in the Chiquitania. On the return trip to Asunción he too was killed in Paraguay. Not until 1767, when the missions had encroached sufficiently on the hostile region and just before the Jesuits were expelled from the New World, did Fr. José Sánchez Labrador manage to travel from Belén in Paraguay to Santo Corazón, the easternmost Chiquitos mission.[7]

Expulsion and recent development

editIn 1750 as a result of the Treaty of Madrid seven missions in present-day Rio Grande do Sul state in Brazil were transferred from Spanish to Portuguese control. The native Guaraní tribes were unhappy to see their lands turned over to Portugal (their enemy for over a century) and they rebelled against the decision, leading to the Guarani War.[14] In Europe, where the Jesuits were under attack, they were accused of supporting the rebellion and perceived as defending the native peoples.[14] In 1758, the Jesuits were accused of a conspiracy to kill the king of Portugal, known as the Távora affair.[15] All members of the Society of Jesus were evicted from Portuguese territories in 1759,[16] and from French territories in 1764.[17] In 1766 Jesuits were accused of causing Esquilache Riots in Madrid; consequently in February 1767, Charles III of Spain signed a royal decree with expulsion orders for all members of the Society of Jesus in Spanish territories.[14]

From then on, spiritual and secular administration were to be strictly separated.[18] At the time of the expulsion, 25 Jesuits served a Christianized population of at least 24,000,[nb 2] in the ten missions of the Chiquitania.[10] The Chiquitos mission properties included 25 estancias (ranches) with 31,700 cattle and 850 horses. Libraries across the settlements held 2,094 volumes.[19]

By September 1767, all but four Jesuits had left the Chiquitania, and they went the following April. The Spanish considered it essential to maintain the settlements as a buffer against Portuguese expansion. The archbishop of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Francisco Ramón Herboso, established a new system of government, very similar to that set up by the Jesuits. He stipulated that each mission be run by two secular (parish) priests, one to take care of the spiritual needs while the other was in charge of all other – political and economic – affairs of the mission administration. One change was that the Indians were allowed to trade. In practice, the shortage of clergy and the low quality of those appointed by the bishop – almost all of whom did not speak the language of the local peoples and in some cases had not been ordained – led to a rapid general decline of the missions. The priests also broke ethical and religious codes, appropriated the major part of the missions' income and encouraged contraband trade with the Portuguese.[18][20]

Within two years of the expulsion, the population in the Chiquitos missions dropped below 20,000.[21] Despite the general decline of the settlements, however, the church buildings were maintained and, in some cases, extended by the towns' inhabitants. The construction of the church in Santa Ana de Velasco falls into this period. Bernd Fischermann, an anthropologist who studied the Chiquitano, suggests three reasons that the Chiquitano preserved the heritage of the Jesuits even after their expulsion:[22] the memory of their prosperity with the Jesuits; the desire to appear as civilized Christians to mestizos and white people; and to preserve the ethnicity that originated from a mix of various culturally distinct groups blended by an enforced common language[nb 3] and customs learned from the Jesuits.

In January 1790, the Audiencia of Charcas ended the diocese’s mismanagement, and temporal affairs were delegated to civil administrators, with the hope of making the missions economically more successful.[18] Sixty years after the expulsion of the Jesuits the churches remained active centers of worship, as the French naturalist Alcide d'Orbigny reported during his mission to South America in 1830 and 1831. Although much diminished economically and politically, the culture the Jesuits established was still evident. According to d'Orbigny, the music at a Sunday mass in San Xavier was better than those he had heard in the richest cities of Bolivia.[23][24] The population of the Chiquitania missions reached a low of around 15,000 inhabitants in 1830.[4] In 1842 the Comte de Castelnau visited the area and, referring to the church in Santa Ana de Velasco, proclaimed: "This beautiful building, surrounded by gardens, presents one of the most impressive views imaginable."[21]

By 1851, however, the reduction system of the missions had disappeared. Mestizos who had moved to the area in their quest for land began to outnumber the original indigenous population. Starting with the creation of the Province of José Miguel de Velasco in 1880, the Chiquitania was split into five administrative divisions. With the rubber boom at the turn of the century, more settlers came to the areas and established large haciendas, moving the economic activities together with the native peoples out of the towns.[21]

In 1931, the spiritual administration of the missions was given to German-speaking Franciscan missionaries. Ecclesiastical control moved back to the area with the creation of the Apostolic Vicariate of Chiquitos in San Ignacio in that year. The churches not only serve the mestizo inhabitants of the villages but present spiritual centers for the few remaining indigenous peoples living in the periphery.[25]

In 1972, the Swiss architect and then-Jesuit priest Hans Roth began an extensive restoration project of the missionary churches and many colonial buildings that were in ruins. These churches exist in their present form as a result of Roth's effort, who worked on the restoration with a few colleagues and many local people until his death in 1999. The restoration works have continued sporadically into the beginning of the 21st century under local leadership.

Six of the reductions were listed as part of the World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1990. The churches of San Ignacio de Velasco, Santiago de Chiquitos and Santo Corazón have been reconstructed from scratch and are not part of the World Heritage Site. In San Juan Bautista only ruins remain. UNESCO listed the site under criteria IV and V, acknowledging the adaption of Christian religious architecture to the local environment and the unique architecture expressed in the wooden columns and banisters. Recently ICOMOS, the International Council on Monuments and Sites, warned that the traditional architectural ensemble that makes up the site has become vulnerable following agrarian reforms from 1953 which threatened the fragile socioeconomic infrastructure of the region. At the time of the nomination, the World Heritage Site was protected by the Pro Santa Cruz committee, Cordecruz,[nb 4] Plan Regulador de Santa Cruz,[nb 5] and the local mayoral offices of the mission towns.[2]

World Heritage Missions

editSan Xavier

editInitially established in 1691, the mission of San Xavier was the first of the missions listed in the World Heritage Site. In 1696, due to the incursion of Paulistas from Brazil in the east, the mission was relocated toward the San Miguel River. In 1698, it was relocated closer to Santa Cruz, but in 1708 was moved away to protect the Indians from the Spaniards. The original inhabitants of San Xavier were the Piñoca tribe. The church was built between 1749 and 1752 by the Swiss Jesuit and architect Fr. Martin Schmid. The school and church, as well as other characteristics of residential architecture, are still visible today in the village. San Xavier was restored by Hans Roth between 1987 and 1993.[3][9][26]

San Rafael de Velasco

editThe mission of San Rafael de Velasco was the second mission built out of the six inscribed the World Heritage Site. Founded in 1695 by the Jesuits Fr. Juan Bautista Zea and Fr. Francisco Hervás, it was moved several times. The mission had to be moved in 1701 and 1705 because of epidemics in the region. In 1719 the mission was moved once more due to fire. Fr. Martin Schmid built the church between 1747 and 1749, which has survived. San Rafael de Velasco was restored between 1972 and 1996 as part of Hans Roth's restoration project.[3][9][26]

San José de Chiquitos

editFounded in 1698 by the Jesuits Fr. Felipe Suárez and Fr. Dionosio Ávila, the mission of San José de Chiquitos was the third mission built of those of the World Heritage Site. At first, the mission was inhabited by the Penoca tribe. The church was built between 1745 and 1760 by an unknown architect. It is built of stone, unlike other mission churches in the area which were built with local adobe and wood. The mission is one of four that remain in their original location. A mortuary chapel (1740), the church (1747), a bell tower (1748), a house for the priests (colegio) and workshops (both 1754) still exist, and were renovated by Hans Roth's restoration project between 1988 and 2003. Restoration efforts continue.[3][9][26]

Concepción

editThe fourth mission in the World Heritage Site, the mission of Concepción, was initially founded in 1699 by the Jesuit priests Fr. Francisco Lucas Caballero and Fr. Francisco Hervás. A nearby mission, San Ignacio de Boococas, was incorporated in 1708. The mission was moved three times: in 1707, 1708 and 1722. The mission was inhabited by the Chiquitanos, the largest tribe in the region. The mission church was constructed between 1752 and 1756, by Fr. Martin Schmid and Fr. Johann Messner. From 1975 to 1996 the mission was reconstructed as part of Hans Roth's restoration project.[3][9][26]

San Miguel de Velasco

editThe fifth mission in the World Heritage Site, that of San Miguel de Velasco, was established by the Jesuits Fr. Felipe Suarez and Fr. Francisco Hervás in 1721. San Miguel was an offshoot of the mission of San Rafael de Velasco, where the population had grown too large. The mission church was built between 1752 and 1759, probably by Fr. Johann Messner, a collaborator with or student of Fr. Martin Schmid. The church was restored by Hans Roth between 1979 and 1983.[3][9][26]

Santa Ana de Velasco

editThe mission of Santa Ana de Velasco was the final World Heritage Site-inscribed mission to be established. It was founded by the Jesuit priest Fr. Julian Knogler in 1755. The original native inhabitants of the missions were the Covareca and Curuminaca tribes, who spoke dialects of the Otuke language.[27] The mission church was designed after the expulsion of the Jesuits between 1770 and 1780 by an unknown architect and built entirely by the indigenous population. The complex, consisting of the church, bell tower, sacristy and a grassy plaza lined by houses, is considered to have the most fidelity to the original plan of the Jesuit reductions. Starting in 1989 and lasting until 2001, the mission underwent partial restoration through the efforts of Hans Roth and his team.[3][9][26]

Architecture

editIn their design of the reductions, the Jesuits were inspired by “ideal cities“ as outlined in works such as Utopia and Arcadia, written respectively by the 16th-century English philosophers Thomas More and Philip Sidney. The Jesuits had specific criteria for building sites: locations with plenty of wood for construction; sufficient water for the population; good soil for agriculture; and safety from flooding during the rainy season. Although most of the missions in the Chiquitania were relocated at least once during the time of the Jesuits, four of ten towns remained at their original sites.[2][4] Wood and adobe were the main materials used in the construction of the settlements.

Mission layout

editThe architecture and internal layout of these missions followed a scheme which was repeated later with some variations in the rest of the missionary reductions. In Chiquitos, the oldest mission, San Xavier, formed the basis for the organizational style, which consisted of a modular structure,[nb 6] the center formed by a wide rectangular square, with the church complex on one side and the houses of the inhabitants on the three remaining sides. The centralized organization of the Jesuits dictated a certain uniformity of measures and sizes. Despite being based on the same basic model, the towns of Chiquitos nonetheless show remarkable variations. For example, the orientation of the settlements toward the cardinal points differed and was determined by individual circumstances.[2][28][nb 7]

Plaza

editThe plaza was an almost square area varying in size from 124 by 148 metres (407 ft × 486 ft) in the older towns of San Xavier and San Rafael de Velasco to 166 by 198 metres (545 ft × 650 ft) in San Ignacio de Velasco. As they were used for religious and civil purposes, these were open spaces free of vegetation except a few palm trees surrounding a cross in the center of the plaza. The evergreen palm trees symbolizing eternal love,[28] deliberately hearkened to Psalm 92:12.[29] Four chapels facing the central cross were placed at the corners of the square and were used in processions. Almost no remains exist of the chapels at the mission sites, as the plazas subsequently were redesigned to reflect the republican and mestizo lifestyle prevalent after the period of the Jesuits. Most have undergone recent expansion as well. Trees and shrubs were planted, and in some cases monuments were erected. Out of the original ten missions, only the plaza at Santa Ana de Velasco does not show major changes, consisting as it did in colonial times, of an open grassy space.[28]

Houses

editThe houses of the natives had an elongated layout, and were arranged in parallel lines extending from the main square in three directions. Those facing the plaza were originally occupied by the chiefs of the indigenous tribes, and often were larger. The architecture of these houses was simple, consisting of large rooms (6x4 meters), walls up to 60 centimetres (2 ft) thick, and a roof made of reed (caña) and wood (cuchi) that reached a height of 5 m (16 ft) in the center. Double doors and open galleries provided protection from the elements. The latter have had a social function as meeting places up to the present day.[30]

Over the last 150 years, this layout has been replaced by the usual Spanish colonial architecture of large square blocks with internal patios. Remnants of the initial design can still be seen in San Miguel de Velasco, San Rafael de Velasco and Santa Ana de Velasco, places that were not as much exposed to modernization as the other settlements.[28]

Church complex

editAlong the fourth side of the plaza lay the religious, cultural and commercial centers of the towns. In addition to the church, which dominated the complex, there would have been a mortuary chapel, a tower and a colegio or "school",[nb 8] connected by a wall along the side of the plaza. Behind the wall and away from the plaza would have been the patio with living quarters for the priests or visitors, rooms for town council matters, for music and storage, as well as workshops, which often were arranged around a second patio. Behind the buildings, a vegetable garden surrounded by a wall and a cemetery likely would have been found. The cemeteries and workshops have disappeared completely from the mission settlements, while the other elements of the church complex still survive to varying degrees. Two stone towers (in San Juan Bautista and San José de Chiquitos) and one of adobe (in San Miguel de Velasco) can be traced back to the time of the Jesuits. Others are of more recent construction, or the result of the conservation and restoration work spearheaded by Roth toward the end of the 20th century. Many of these are tall wooden constructions open on all sides. Of the Jesuit schools only those in San Xavier and Concepción are preserved entirely. Like the houses of the indigenous residents, the buildings of the church complex were single-level ones.[nb 9]

Church

editOnce a settlement had been established, the missionaries, working with the native population, began to erect the church, which served as the educational, cultural and economic center of the town. The initial church in each mission (except in Santa Ana de Velasco) was temporary, essentially no more than a chapel and built as quickly as possible of local wood, unembellished save for a simple altar. The Jesuit masterpieces seen today general were erected several decades into the settlements’ existence. Fr. Martin Schmid, Swiss priest and composer, was the architect for at least three of these missionary churches: San Xavier, San Rafael de Velasco, and Concepción. Schmid combined elements of Christian architecture with traditional local design to create a unique baroque-mestizo style. Schmid placed a quotation from the Genesis 28:17[31] above the main entrance of each of the three churches. In San Xavier the quotation is in Spanish: CASA DE DIOS Y PUERTA DEL CIELO ; and in Latin at the other two churches: DOMUS DEI ET PORTA COELI, meaning The house of god and the gate of heaven.[26]

The construction of the restored churches seen today falls in the period between 1745 and 1770 and is characterized by the use of locally available natural materials like wood, used in the carved columns, pulpits and sets of drawers. Artistic adornments were added even after the Jesuits’ expulsion in 1767, until around 1830.[26] Some of the altars are covered in gold. Often the walls of the mission churches were made of adobe, the same material that had been used for the houses of the natives. In San Rafael de Velasco and San Miguel de Velasco, mica also was used on the walls, giving them an iridescent effect. The construction of the church in San José de Chiquitos is an exception: inspired by an unknown baroque model, it has a stone façade. The only other example where stone was used on a grand scale is in the construction of San Juan Bautista, although only the ruins of a tower remain.[26]

All of the churches consist of a wooden skeleton with columns, fixed in the ground, which provided stability to the building and supported the tile-covered roof. The adobe walls were placed directly on the ground, virtually independent of the wooden construction, and had no supporting role. Porticos and a large porch roof provided protection from the heavy tropical rains. The floor was covered in tiles which, like those of the roof, were produced in local tile works. The churches have a barn-like appearance, albeit of monumental size (width: 16–20 metres (52–66 ft), length: 50–60 metres (160–200 ft) height: 10–14 metres (33–46 ft)) with a capacity for more than 3,000 people, with a wide structure and distinctive low-hanging eaves. This style also is evident in the building method of native community houses.[26]

The construction of the church required a major effort by the community and employed hundreds of indigenous carpenters.[13] Fr. José Cardiet described the process:[32]

All these buildings are made in a different way of those made in Europe: because the roof is built first and the walls afterwards. First large tree trunks are buried in the soil, these are worked by adz. Above these they place the beams and sills; and above these the trusses and locks, tins and roof; after that the foundations of stone are placed, and about 2 or 3 spans above the surface of the soil, and from here upwards they place the walls of adobe. The wooden trunks or pillars, which are called horcones, remain in the central part of the walls, carrying the complete weight of the roof and no weight on the walls. In the central naves and in the place where the wall will be placed, 9 feet deep holes are made, and with architectural machines they introduce the carved horcones in the form of columns. The 3 meters (9 feet) stay inside the soil and are not carved, and keep part of the trees roots for greater strength, and these parts are burned so they may resist the humidity.

The walls were decorated with cornices, moldings, pilasters and at times blind arcades. First the walls were plastered entirely by a mix of mud, sand, lime and straw, both inside and outside. Paint in earth tones was applied over the lime whitewash, and ornaments were drawn, featuring elements from flora and fauna, as well as angels, saints and geometrical patterns. As noted above, in some cases mica was used to decorate the walls, columns and woodworks. Large oval "oeil-de-boeuf" windows, surrounded by relief petals, above the main doors are a characteristic feature.[13]

The churches had three aisles, divided by wooden columns, often solomonic columns, carved with twisted fluting resembling those at St. Peter's baldachin in St Peter's, Rome. Until modern times, there were no pews so the congregation had to kneel or sit on the floor. A variety of fine pieces of art adorn the inside of the churches, notably their altars, which are sometimes covered in gold, silver or mica. Especially remarkable are the pulpits made of brightly painted wood and supported by carved sirens. The pulpit in the church of San Miguel de Velasco features motifs derived from local vegetation. Elements specific to the Chiquitos missions exist also in other decorations. The altars of the churches of San Xavier and Concepción include depictions of notable Jesuits together with indigenous peoples. There remain a handful of original sculptures in retablos often depicting Madonnas, the crucifixion, and saints, carved in wood and then painted. These sculptures exhibit a style unique to the Chiquitos region, differing from that of the reductions in Paraguay or the Bolivian highlands. The tradition of figure carving has been preserved to the present day in workshops where carvers make columns, finials and windows for new or restored churches or chapels in the area. In addition, carvers produce decorative angels and other figures for the tourist market.[13]

Restoration

editThe missionary churches are the true architectural highlights of the area. Hans Roth initiated an important restoration project in these missionary churches in 1972. In San Xavier, San Rafael de Velasco, San José de Chiquitos, Concepción, San Miguel de Velasco and Santa Ana de Velasco, these churches have undergone meticulous restoration. In the 1960s, the San Ignacio de Velasco church (a non-current UNESCO WHS) was replaced with modern construction; in the 1990s, Hans Roth and his co-workers brought the restoration as close as possible to the original edifices. In addition to the churches, Roth constructed more than a hundred new buildings, including schools and houses. He also founded museums and archives.[25]

Roth researched and recovered the original techniques used to construct churches prior to the restorations. He installed new building infrastructure including saw mills, locksmith shops, and carpentry and repair shops, and trained local people in traditional crafts. European volunteers, non-profit organizations, the Catholic Church, and the Bolivian Learning Institute (IBA) helped in the project.

Roth convinced the local inhabitants of the importance of the restoration works, which required a large labor force: typically 40 to 80 workers in towns with populations of 500 to 2,000 were required for church restoration. The effort indicates the strength of and commitment to the unique shared heritage present in the towns. This restoration has resulted in a revival of local traditions and a qualified workforce.[32][nb 10]

Life in the mission towns

editThe reductions were self-sufficient indigenous communities of 2,000–4,000 inhabitants, usually headed by two Jesuit priests and the cabildo (town council and cacique (tribal leader), who retained their functions and played the role of intermediaries between the native peoples and the Jesuits.[4][33] However, the degree to which the Jesuits controlled the indigenous population for which they had responsibility and the degree to which they allowed indigenous culture to function is a matter of debate, and the social organization of the reductions have been variously described as jungle utopias on the one hand, to theocratic regimes of terror, the former description being much closer to the mark.[8]

Many Indians who joined the missions were looking for protection from Portuguese slave traders or the encomienda system of the Spanish conquistadores. In the reductions, the natives were free men. The land in the missions was common property. After a marriage, individual plots were assigned to newly founded families.[3] For the Jesuits, the goal was always the same: to create cities in harmony with the paradise where they had encountered the indigenous peoples.[20][34]

Though the settlements were officially a part of the Viceroyalty of Peru through the Royal Audiencia of Charcas and of the diocese of Santa Cruz in church affairs, their remoteness made them effectively autonomous and self-sufficient. As early as 1515, the Franciscan friar Bartolomé de las Casas had initiated a "foreigner law" for the "'Indian people'", and no white or black man, other than the Jesuits and authorities, was allowed to live in the missions. Merchants were allowed to stay for three days at most.[2][4]

Languages

editThe Jesuits quickly learned the languages of their subjects, which eased the missionary work and contributed to the success of the missions. Although initially each mission were conceived as home to one specific tribe, numerous tribal families lived in the Chiquitania, and often were gathered in next to each other on the same mission. According to a report from 1745, of the 14,706 people living in the missions, 65.5% spoke Chiquitano, 11% Arawak, 9.1% Otuquis, 7.9% Zamucos, 4.4% Chapacura and 2.1% Guaraní.[11] It should, however, be understood that by this time most of the inhabitants of these missions spoke Chiquitano as a second language. Such ethnic diversity is unique among the Jesuit missions in America.[10] Reflecting the view of the colonial powers, the Jesuit records only distinguished between Christian and non-Christian Indios.[11] Eventually Gorgotoqui, the formal name for language spoken by the Chiquitano tribe, became the lingua franca of the mission settlements, and the numerous tribes were culturally united in the Chiquitano ethnic group.[2][3][33] By 1770, within three years of the expulsion of the Jesuits, Spanish authorities instituted a new policy of forced "castilianization" or "Hispanicization" of the language, thereby causing the number of speakers of native languages to decline.[35]

Economy

editTraditionally most of the Chiquitos tribes practiced swidden agriculture, growing maize and yuca on a small scale.[11] After contact with the Spanish, cocoa and rice also were cultivated. Hunting and fishing provided additional nutrition in the dry season. The Jesuits introduced cattle breeding.[3][16]

In each settlement, one of the Jesuits was responsible for church matters, while another dealt with commercial affairs and the general well-being of the community. As the Swiss priest, musician and architect Fr. Martin Schmid wrote in a 1744 letter from San Rafael:[4]

„...the Missionary Priests... are not only parish priests who have preach, hear confessions and govern souls, they are also responsible for the life and health of their parishioners and must provide all the things needed by their towns, because the soul cannot be saved if the body dies. Therefore, the missionaries are town counsellors and judges, doctors, bleeders, masons, carpenters, ironsmiths, locksmiths, shoemakers, tailors, millers, backers, cooks, shepherds, gardeners, painters, sculptors, turners, carriage makers, brick makers, potters, weavers, tanners, wax and candle makers, tinsmiths, and any artisans which may be required in a republic.“

The Jesuits administered labor, the introduction of new technologies, and the disposition of goods. They designated that each family receive all that was necessary to live. The Jesuits did not rely on donations, because by right the priests received a fixed income (usually insufficient for their needs) from the community to support their work. The thriving economy in the reductions enabled them to export surplus goods to all parts of Upper Peru, although ironically not to Paraguay – the region the Jesuits most wanted to reach. The income was used to pay royal tributes and to purchase goods not locally available, such as books, paper, and wine, from as far away as Europe.[4] In the missions themselves money was not used.[3] This laid the foundation of the belief that the Jesuits were guarding immense riches acquired through local labor. In reality the communities were economically successful but hardly constituted any important source of income for the Jesuit order.[8]

All the inhabitants, including the young and elderly, were subject to a schedule of alternating work, religious practice, and rest. According to d'Orbigny, the inhabitants of the Chiquitos missions enjoyed considerably more freedom than those in the Mojos missions. There was also less time spent practicing religion.[33] The catechumens were instructed by the Jesuits in various arts. They learned very quickly and soon became proficient carpenters, painters, weavers, sculptors and artisans. Each settlement had its own set of craftsmen; as a result, in addition to the caciques, a new social class of craftsmen and artisans emerged. This group and the rest of the population, who worked primarily in agriculture or cattle raising, were each represented by two alcaldes.[33] Initially the main commercial products included honey, yerba maté, salt, tamarind, cotton, shoes, and leather.[4] Later, artisans exported musical instruments, liturgical items, rosaries, and silverware.[4]

Music

editMusic played a special part in all aspects of life and in the evangelization of the natives.[3][36] Realizing the musical capacities of the Indians, the Jesuits sent important composers, choir directors, and manufacturers of musical instruments to South America. The most famous was probably the Italian baroque composer Domenico Zipoli, who worked in the reductions in Paraguay. Fr. Johann Mesner and Fr. Martin Schmid, two Jesuit missionaries with musical talent, went to the Chiquitania.[nb 11] Schmid in particular was responsible for this skill being developed to such a high degree that polyphonic choirs would perform, and whole orchestras would play Baroque operas on handmade instruments. He directed the production of violins, harps, flutes, and organs, and wrote and copied masses, operas, and motets. He built an organ with six stops in Potosí, disassembled it, transported it by mules over a distance of 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) on a difficult road to the remote mission of Santa Ana de Velasco, and re-assembled it there from hand. It is still is use. The Jesuits used musical lessons as a first step to the Christianization of the natives.[3][23]

As Schmid, who also acted as a composer, wrote in a 1744 letter from San Rafael de Velasco:[4]

„“...In all these towns the sound of my organs already can be heard. I made a pile of all kind of musical instruments and taught the Indians how to play them. Not a single day passes without the sound of songs in our churches... and I sing, play the organ, the zither, the flute, the trumpet, the psalter and the lyre, in high mode and low mode. All these musical art forms, which I ignored partially, I am able to practice now and teach them to the children of the natives. Your Reverence would be able to observe here, how children which were torn away from the jungle just a year ago, together with their parents are able today to sing well and with an absolutely firm beat, they play the zither, lyre and the organ and dance with precise movements and rhythm, that they might compete with the Europeans themselves. We teach these people all these mundane things so they may get rid of their rude customs and resemble civilized persons, predisposed to accept Christianity.”

Today

editSome Jesuit institutions still exist in the Chiquitania. For example, the towns of San Rafael de Velasco, San Miguel de Velasco, Santa Ana de Velasco and San Ignacio de Velasco have functioning town councils (cabildos), and the caciques and the sexton still retain their capacities.[4] The majority of the population of the Chiquitania is staunchly Catholic; the Chiquitano cosmovision is now only a dimly understood mythology for its inhabitants. Between 1992 and 2009, the populations of San Xavier and especially Concepción tripled, and more than doubled in San Ignacio de Velasco, now the region's fastest-growing municipality. In other mission towns the population also increased, albeit on a smaller scale. As of 2011, San José de Chiquitos, San Xavier and Concepción have around 10,000 inhabitants each; and San Ignacio de Velasco, the largest town in the Chiquitania, has about 35,000 and is now boasts a campus of a national university. On the other hand, in Santa Ana de Velasco there are currently only a few hundred people.[37] The remoter settlements of Santiago de Chiquitos and Santo Corazón are quite small as well. According to various sources, in Bolivia the number of ethnic Chiquitanos is between 30,000 and 47,000 of which less than 6,000 – mainly elderly people – still speak the original language. Only a few hundred are monolingual in the Chiquitano language.[38]

Economically, the area depends on agriculture. Maize, rice, yuca, cotton and heart of palm are produced and exported. Cattle ranching and the industrial processing of milk and cheese have been developed extensively in recent years. Crafts, often carved of wood using the same techniques as in colonial times, provide additional income.[6] Since the launch of the Jesuit Mission Circuit – a marketing label to promote regional tourism[nb 12] – in 2005, craftsmanship and tourism have been closely related.

The musical festivals and concerts held regularly in the Chiquitos formermission towns testify to the living heritage of this art form.[23][39][40] Some of the original instruments and sculptures made by Fr. Martin Schmid and his apprentices survive in small museums in the mission towns, most notably in Concepción which also houses the music archive. In San Xavier, San Rafael de Velasco and Santa Ana de Velasco three original harps from the time of the Jesuits are preserved.[41] The church in Santa Ana de Vealsco also houses the only original organ in Chiquitos, transported there from Potosí by mule, accompanied by Schmid in 1751.[3] More than a dozen orchestras and choirs brought together by the Sistema de Coros y Orquestas (SICOR) dot the area.[42][43][nb 11]

Since 1996, the nonprofit institution Asociacion Pro Arte y Cultura (APAC) has organized the biennial Festival Internacional de Musica Renacentista y Barroca Americana "MISIONES DE CHIQUITOS".[39]

Starting in 1975, restoration work on the church (now cathedral) of Concepción unearthed more than 5,000 musical scores from the 17th and 18th centuries. Later another 6,000 scores were found in Moxos and several thousand additionally in San Xavier. Some of these works have been interpreted at the 2006 and 2008 festivals. The statistics of these festivals over the years is as follows:[39]

| 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | 14 | 32 | 28 | 30 | 42 | 44 | 50 | 45 | 49 |

| Concerts | 32 | 68 | 76 | 77 | 122 | 143 | 165 | 121 | 118 |

| Musicians | 355 | 517 | 402 | 400 | 980 | 623 | 600 | 800 | 800 |

| Countries | 8 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 19 | 24 | 14 | 19 |

| Venues | 3 | 9 | 9 | 14 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 12 | 12 |

| Audience | 12,000 | 20,000 | 30,000 | 40,500 | 70,000 | 71,000 | 75,000 | 60,000 | 55,000 |

The festival is carried out in the designated Plazas Misionales (among other places), usually housed in churches and also in the main plaza of Santa Cruz. In one event, orchestras of various countries compete against each other. One of the local orchestras, Orquesta Urubicha, is made up of people native to the ex-missions who use instruments which they build themselves according to plans left by the Jesuit missionaries.

Tourism

editShortly after the start of the restoration effort, the potential for tourism in the missions was assessed in a report[nb 13] published by UNESCO in 1977.[2]

To promote the missions as a tourist destination, travel agencies, chambers of commerce and industry, the towns' mayors, native communities and other institutions organized the Lanzamiento mundial del Destino Turístico "Chiquitos", Misiones Jesuíticas de Bolivia, a five-day tourist event[nb 14] lasting from March 23–27, 2006.[44] Journalists and international tour operators were shown the important tourist attractions, and introduced to the culture through visits to museums, local workshops, various concerts, native dances, high masses, processions, crafts festivals, and local cuisine. The organisers’ goal initially was to raise the number of tourists from 25,000 to 1 million per year over a ten-year period, which would have represented US$400 million of income.[45][46] Subsequently, in the face of lack of support from the Bolivian government and the downturn of the national and local economies, a more modest goal of attracting between 200,000 and 250,000 people per annum was established.

Tourism is now an important source of income for the region, amounting in Concepción Municipality alone to US$296,140, or 7.2% of the annual gross production. An additional US$40,000 or 1% comes from crafts.[47] According to a report published by the "Coordinadora Interinstitucional de la Provincia Velasco" in 2007, 17,381 people visited San Ignacio de Velasco, the largest town in the region, as tourists in 2006. About 30% of them came from outside of Bolivia. The main attraction for tourists are the nearby missions of San Miguel de Velasco, San Rafael de Velasco and Santa Ana de Velasco.[nb 15] Tourism to San Ignacio de Velasco generated 7,821,450 Bolivianos in income in 2006.[48] Tourism income is ostensibly translated to improvements in the infrastructure, although there has been criticism that earmarked funds do not always reach their intended destinations. Other than cultural tourism to the missionary circuit and musical festivals, the region offers many natural attractions like rivers, lagoons, hot springs, caves and waterfalls, although there is no infrastructure to support tourism in this regard.

Cultural references

editMany elements of the early days of the Jesuit missions are shown in the movie The Mission, although the movie attempts to depict life in the Guaraní missions of Paraguay, not those of the Chiquitos missions, which were considerably more culturally expressive. The events around the expulsion of the Jesuits (the Extrañamiento) are depicted in Fritz Hochwälder's play Das heilige Experiment (The Strong are Lonely). Both are set in Paraguay. It has been suggested[49] that Das heilige Experiment sparked interest in the 20th century among scholars in the forgotten Jesuit missions.

See also

editJesuit missions in neighboring countries

- Jesuit Block and Estancias of Córdoba (Argentina)

- Jesuit missions of the Guaraní (Argentina and Brazil)

- Jesuit missions of La Santisima Trinidad de Paraná and Jesús de Tavarangue (Paraguay)

Notes

edit- ^ There were several reasons for constructing the doors in such a way: they kept out mosquitoes, flies and cold southerly winds; and they provided protection from enemies.

- ^ which included only those who had been baptized. The total population was estimated to be around 37,000

- ^ Chiquitano was chosen by the Jesuits as the lingua franca of all the Chiquitos missions

- ^ a regional public agency in Santa Cruz Department responsible for land improvements

- ^ a regional technical authority in Santa Cruz Department responsible for urban planning and ground use

- ^ Modular structure refers to the basic building blocks that make up the settlement: plaza, church complex, houses. These parts are similar in all the settlements but were combined in various ways to produce distinct settlements.

- ^ The major features of the ideal layout plan were common among the Jesuit reductions. A general impression is given by a drawing of the mission in Concepción de Moxos by Victor Hugo Limpias in: Ortiz, Victor Hugo Limpias (June 2008). "El Barroco en la misión jesuítica de Moxos" [Moxos Jesuitic mission's Barroc art style]. Varia Historia (in Spanish). 24 (39): 227–254. doi:10.1590/S0104-87752008000100011.

- ^ The term school refers to the priests' house.

- ^ In San Rafael de Velasco there originally existed a two-storied "guest house" as part of the school.

- ^ The Cathedral of Concepción, Chiquitos, built by Fr. Martin Schmid, in a historic photograph from the early 20th century (by E. Kühne): Concepción church

- ^ a b Audio recordings of works by Jesuit composers can be found at Chiquitos – Musica. Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ Apart from the six World Heritage Missions, the mission of San Ignacio de Velasco is part of this circuit.

- ^ Martini, Jose Xavier (1977). Las Antiguas misiones jesuiticas de Moxos y Chiquitos. Posibilidades de su aprovechamiento turistico (in Spanish). Paris: UNESCO. p. 131.

- ^ One day of the five was spent in the Pantanal.

- ^ 83%/83%/93% of visitors to San Ignacio de Velasco also visited Santa Ana de Velasco /San Rafael de Velasco /San Miguel de Velasco

References

edit- ^ http://festivalesapac.com/ Asociación Pro Arte y Cultura

- ^ a b c d e f g h ICOMOS (1990). Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos (PDF). Advisory Body Evaluation No. 529. UNESCO. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Lasso Varela, Isidro José (2008-06-26). "Influencias del cristianismo entre los Chiquitanos desde la llegada de los Españoles hasta la expulsión de los Jesuitas" (in Spanish). Departamento de Historia Moderna, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia UNED. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Roth, Hans. "Events that happened at that time". Chiquitos: Misiones Jesuíticas. Retrieved 2009-01-21.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Chiquitano". Ethnologue. SIL International. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ a b "I Congreso Internacional Chiquitano, 22–24 May 2008". San Ignacio de Velasco. Archived from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ a b c "Provincia Boliviana de la Compañia de Jesús" (in Spanish). Jesuitas Bolivia-Online. 2005. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ^ a b c Lippy, Charles H, Robert Choquette and Stafford Poole (1992). Christianity comes to the Americas: 1492–1776. New York: Paragon House. pp. 98–100. ISBN 1-55778-234-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Groesbeck, Geoffrey A. P. (2008). "A Brief History of the Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos (Eastern Bolivia)". Colonialvoyage. Archived from the original on 2009-01-06. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ a b c d Jackson, Robert H. "Ethnic Survival and Extinction on the Mission Frontiers of Spanish America: Cases from the Río de la Plata Region, the Chiquitos Region of Bolivia, the Coahuila-Texas Frontier, and California" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-12-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e Jackson, Robert H. "La raza y la definición de la identidad del "Indio" en las fronteras de la América española Colonial". Revista de Estudios Sociales (26). ISSN 0123-885X. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ Gott, Richard (1993), Land Without Evil: Utopian Journeys across the South American Watershed', London: Verso, pp. 133-135

- ^ a b c d Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2003-01-28). "Missions in a Musical Key. The Jesuit Reductions of Chiquitos, Bolivia". Company Magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ a b c Richard Gott (1993). Land Without Evil: Utopian Journeys Across the South American Watershed (illustrated ed.). Verso. p. 202. ISBN 0-86091-398-8. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Kenneth Maxwell (2004). Conflicts & conspiracies: Brazil and Portugal 1750–1808 (illustrated ed.). Routledge. 203. ISBN 0-415-94988-2. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ a b Alden, Dauril (February 1961). "The Undeclared War of 1773–1777 and Climax of Luso-Spanish Platine Rivalry". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 41 (1). Duke University Press: 55–74. doi:10.2307/2509991. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2509991.

- ^ Ganson, Barbara Anne (2006). The Guarani Under Spanish Rule in the Rio de la Plata (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-8047-5495-0. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ a b c Merino, Olga; Linda A. Newson (1995). "Jesuit Missions in Spanish America: The Aftermath of the Expulsion" (PDF). In David J. Robinson (ed.). Yearbook 1995. Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers. Vol. 21. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 133–148. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-11. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ Margarete Payer; Alois Payer (September 2002). "Teil 2: Chronik Boliviens, 7. Von 1759 bis zur Französischen Revolution (1789)". Bibliothekarinnen Boliviens vereinigt euch! Bibliotecarias de Bolivia ¡Uníos! Berichte aus dem Fortbildungssemester 2001/02 (in German). Tuepflis Global Village Library. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

Bei der Aufhebung der Jesuitenmissionen werden u.a. folgende Besitzungen inventarisiert:...

- ^ a b Bravo Guerreira, María Concepción (1995). "Las misiones de Chiquitos: pervivencia y resistencia de un modelo de colonización" (PDF). Revista Complutense de Historia de América (in Spanish) (21): 29–55. ISSN 1132-8312. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ a b c Groesbeck, Geoffrey A. P. (2008). "The long silence: the Jesuit missions of Chiquitos after the extrañamiento". Colonialvoyage. Archived from the original on 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ Fischermann, Bernd (2002-01-29). "Zugleich Indianer und Campesino – Die Kultur der Chiquitano heute" (in German). Archived from the original on 2007-12-08. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ a b c Torales Pacheco, Maria Cristina (2007). Karl Kohut (ed.). Desde los confines de los imperios ibéricos: Los jesuitas de habla alemana en las misiones americanas. Diversidad en la unidad: los jesuitas de habla alemana en Iberoamérica, Siglos XVI-XVIII (in Spanish). Iberoamericana Editorial. ISBN 978-84-8489-321-9. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ d'Orbigny, Alcides (1845). Fragment d'un voyage au centre de l'Amerique Meridionale (in French). P. Bertrand (ed.). Paris. Retrieved 2009-01-18.

- ^ a b Kühne, Eckart (2002-08-27). The construction and restoration of the 18th century missionary churches of Chiquitos in eastern Bolivia (PDF). ETH Zurich — North-South Centre Research for Development, Colloquium 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Groesbeck, Geoffrey A. P. (2007). "The Jesuit Missions: Their Churches". La Gran Chiquitania. Archived from the original on 2009-04-06. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- ^ a b c d Roth, Hans. "The ideal layout plan for the Chiquito missions". Chiquitos: Misiones Jesuíticas. Archived from the original on 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ Psalms 92:12

- ^ Rodríguez Hatfield, María Fabiola (2007). "Misiones Jesuitas de Chiquitos: La utopía del reino de Dios en la tierra" (in Spanish). Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Genesis 28:17

- ^ a b Roth, Hans; Eckart Kuhne. "This new and beautiful church: The construction and restoration of the churches built by Martin Schmid". Chiquitos: Misiones Jesuíticas. Archived from the original on 2009-02-02. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ a b c d d'Orbigny, Alcides (1843). Descripción Geográfica, Histórica y Estadística de Bolivia (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ Alvestegui Müller, Marie Isabel. "Die Jesuitenmissionen der Chiquitos". Der Untergang der Reduktionen. Retrieved 2009-01-21.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Matthias Brenzinger (2007). Language diversity endangered. Trends in linguistics. Studies and monographs. Vol. 181. Walter de Gruyter. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-11-017049-8.

- ^ Wilde, Guillermo (2007). Patricia Hall (ed.). "Toward a Political Anthropology of Mission Sound: Paraguay in the 17th and 18th Centuries". Music and Politics. 1 (2). Translation by Eric Ederer. ISSN 1938-7687. Archived from the original on 2008-10-28. Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ "Santa Cruz – largest cities and towns and statistics of their population". World Gazetteer. Retrieved 2009-01-19.[dead link]

- ^ Fabre, Alain (2008-07-21). "Chiquitano" (PDF). Diccionario etnolingüístico y guía bibliográfica de los pueblos indígenas sudamericanos (in Spanish). Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ a b c "Festivales APAC" (in Spanish). Asociacion Pro Arte y Cultura. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ Busqué, Jordi. "Music in Chiquitania & Guarayos". Jordi Busqué. Archived from the original on 2008-06-05. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ^ Areny, Pedro Llopis (June 2004). "Arpa misional Chiquitania". Arpas antiguas de España (in Spanish). Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ^ "Sistema de Coros y Orquestas" (in Spanish). SICOR. Archived from the original on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ^ Mcdonnell, Patrick J. (2006-05-06). "How they go for Baroque in Bolivia". Los Angeles Times (E-1 ed.). ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ^ Rivero, Juan Carlos (2006-03-04). "Algo que nos une: destino Chiquitos". El Deber – Editorial (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ "Chiquitos: hoy es el lanzamiento del Destino Turístico". El Nuevo Día – Sociedad (in Spanish). 2006-03-23. Retrieved 2009-02-16.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Prefectura del Departamento de Santa Cruz – Bolivia (January 2006). "Chiquitos abre sus puertas al mundo". anyelita (in Spanish). anyela. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ Molina, Gonzalo Coimbra (2007-03-15). Artículo Analítico: Desarrollo Humano Sostenible en las Misiones Jesuíticas de Chiquitos de Bolivia El caso del municipio de Concepción. Proyecto de Desarrollo Territorial Rural a Partir de Productos y Servicios con Identidad (in Spanish). RIMISP. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ El turismo en Velasco – Datos, cifras e información sobre los visitantes de San Ignacio (PDF) (in Spanish). Coordinadora Interinstitucional de la Provincia Velasco. November 2007. Retrieved 2009-08-17.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Forster, Nicolas (2002). "Der Jesuitenstaat in Paraguay" (PDF). Seminar für neuere Geschichte, term paper (in German). University Vienna. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[permanent dead link]

Further reading

editHistoric accounts

editOf the primary sources, i.e., those composed by the Jesuits themselves during the years 1691 through 1767, those that have been extensively researched (many as yet have not been thoroughly examined) are few. The most useful is the monumental Historia general de la Compañía de Jesús en la Provincia del Perú: Crónica anómina de 1600 que trata del establecimiento y misiones de la Compañía de Jesús en los países de habla española en la América meridional, vol. II, edited by Francisco Mateos (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1944). Also of importance is the unedited archive of correspondence from the Jesuits of Paraguay from the years 1690–1718. Collectively known as “Cartas a los Provinciales de la Provincia del Paraguay 1690-1718,” these manuscripts are housed in the Jesuit Archives of Argentina in Buenos Aires, which also contain the invaluable annals of the Paraguay Province of the Company of Jesus, covering the years 1689–1762. The German edition of Fr. Julián Knogler's Inhalt einer Beschreibung der Missionen deren Chiquiten, Archivum Historicum Societatis Jesu, 39/78 (Rome: Company of Jesus, 1970) is indispensable, as is his account Relato sobre el país y la nación de los Chiquitos en las Indias Occidentales o América del Sud y en la misiones en su territorio, for a condensed version of which, see Werner Hoffman, Las misiones jesuíticas entre los chiquitanos (Buenos Aires: Fundación para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura, 1979). Fr. Juan de Montenegro's Breve noticia de las missiones, peregrinaciones apostólicas, trabajos, sudor, y sangre vertida, en obsequio de la fe, de el venerable padre Augustín Castañares, de la Compañía de Jesús, insigne missionero de la provincia del Paraguay, en las missiones de Chiquitos, Zamucos, y ultimamente en la missión de los infieles Mataguayos, (Madrid: Manuel Fernández, Impresor del Supremo Consejo de la Inquisición, de la Reverenda Cámara Apostólica, y del Convento de las Señoras de la Encarnación, en la Caba Baxa, 1746) and Fr. Juan Patricio Fernández's Relación historial de las misiones de los indios, que llaman chiquitos, que están a cargo de los padres de la Compañía de Jesús de la provincia del Paraguay (Madrid: Manuel Fernández, Impresor de Libros, 1726) are also valuable. There are other primary sources as yet unexamined, the majority of which are archived in Cochabamba, Sucre, and Tarija (in Bolivia); Buenos Aires, Córdoba, and Tucumán (in Argentina); Asunción (Paraguay); Madrid; and Rome.

- Castelnau, Francis (1850). Expédition dans les parties centrales de l'Amérique du Sud, de Rio de Janeiro à Lima: et de Lima au Para (in French).

- Demersay, L. Alfred (1860). Histoire physique, économique et politique du Paraguay et des établissements des Jésuites (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette.

- Demersay, L. Alfred (1864). Histoire physique, économique et politique du Paraguay et des établissements des Jésuites (in French). Vol. 2. Paris: Librairie de L. Hachette.

- Fernandez, Juan Patricio (1895). Relacion Historial de Las Misiones de Indios Chiquitos que en el Paraguay tienen los padres de la Compañia de Jesús. Colección de libros raros ó curiosos que tratan de América (in Spanish). Vol. 1. Madrid: Victoriano Suárez.

- Fernandez, Juan Patricio (1896). Relacion Historial de Las Misiones de Indios Chiquitos que en el Paraguay tienen los padres de la Compañia de Jesús (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Asunción del Paraguay: A. de Uribe y Compañia.

- Ibagnez, Bernardo (1774). Jesuitisches Reich in Paraguay: durch Originaldocumente der Gesellschaft Jesu bewiesen von dem aus dem Jesuiterorden verstoßenen Pater Ibagnez (in German). Cölln: Peter Marteau.

References to many others are found in the extensive bibliography offered by Roberto Tomichá Charupá, OFM, in La Primera Evangelización en las Reducciones de Chiquitos, Bolivia (1691-1767), pp. 669–714.

Modern books

edit- Bösl, Antonio Eduardo (1987). Una Joya en la selva boliviana (in Spanish). Zarautz, Spain: Itxaropena. ISBN 978-84-7086-212-0.

- Cisneros, Jaime (1998). Misiones Jesuíticas (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). La Paz: Industrias Offset Color S.R.L.

- Groesbeck, Geoffrey A.P. (2007). "A Brief History of the Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos" (PDF). Bolivian Studies. Springfield, IL: University of Illinois. ISSN 2156-5163. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-12-07. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- Groesbeck, Geoffrey A.P. (2012). Evanescence and Permanence: Toward an Accurate Understanding of the Legacy of the Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos. Archived from the original on 2012-12-30. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Groesbeck, Geoffrey A.P. (2012). The Long Silence: The Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos after the Extrañamiento. Archived from the original on 2012-12-30. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- Molina Barbery, Placido; Alcides Parejas; Ramón Gutiérrez Rodrigo; Bernd Fischermann; Virgilio Suárez; Hans Roth; Stefan Fellner; Eckart Kühne; Pedro Querejazu; Leonardo Waisman; Irma Ruiz; Bernardo Huseby (1995). Pedro Querejazu (ed.). Las misiones jesuíticas de Chiquitos (in Spanish). La Paz, Bolivia: Fundación Banco Hipotecario Nacional, Línea Editorial, La Papelera. p. 718. OL 543719M.

- Parejas Moreno, Alcides (2004). Chiquitos: a look at its history. Milton Whitaker (trans.), Ana Luisa Arce de Terceros (trans.). Santa Cruz de la Sierra: Asociación Pro Arte y Cultura. p. 93. ISBN 99905-0-802-X.

- Tomichá Charupá, Roberto (2002). La Primera Evangelización en las Reducciones de Chiquitos, Bolivia (1691-1767) (in Spanish). Cochabamba: Editorial Verbo Divino. p. 740. ISBN 978-99905-1-009-6.

See also

editExternal links

edit- Misiones Jesuiticas (English/Spanish)

- Misiones Jesuitas de Bolivia rutas

- Jesuit Missions of Chiquitos travel guide from Wikivoyage

- La Gran Chiquitania: The Last Paradise.

- Illustrated report on the visit of the World Heritage site