Jerusalem International Airport[a] (IATA: JRS, ICAO: LLJR, OJJR) was a regional airport located in the city of Jerusalem. When it was opened in 1925, it was the first airport in the British Mandate for Palestine.[3]

Jerusalem International Airport נְמַל הַתְּעוּפָה יְרוּשָׁלַיִם مطار القدس الدولي | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Defunct (formerly military and public) | ||||||||||

| Operator | Israel Defense Forces Israel Airports Authority | ||||||||||

| Location | Jerusalem | ||||||||||

| Opened | May 1924[1] | ||||||||||

| Closed | 8 October 2000 [2] | ||||||||||

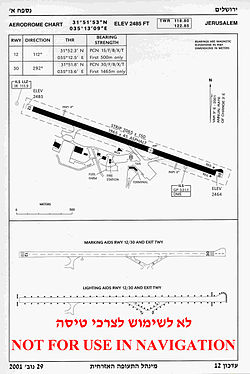

| Elevation AMSL | 2,485 ft / 757 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 31°51′53″N 35°13′09″E / 31.86472°N 35.21917°E | ||||||||||

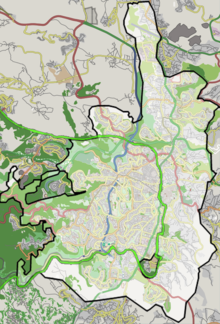

| Map | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Under the British Mandate, the former Cyprus Airways flew to the airport, and this continued intermittently after Cyprus gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1960.[4] Following the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the airport was occupied by Jordan alongside the rest of the West Bank, and in 1950, it became part of the Jordanian annexation of the West Bank. Between 1948 and 1967, Royal Jordanian Airlines, as well as Middle East Airlines from Lebanon, operated daily commercial flights to and from the airport.[5][6]

In 1967, Israel won the Six-Day War and began militarily occupying all previously Jordanian-annexed territory, including the airport. In 1981, Israel effectively annexed the airport as part of the Jerusalem Law. Between 1967 and 2000, Arkia and El Al operated daily commercial flights to and from the airport;[7][8] Israel closed the airport to all civilian traffic following the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000.[9]

History

editUntil 1927, the airfield in Kalandia was the only airport in the British Mandate for Palestine. It was used by the British military authorities and prominent guests bound for Jerusalem.[10] In 1931, the Mandatory government expropriated land from the Jewish village of Atarot to expand the airfield, in the process demolishing homes and uprooting fruit orchards.[11] In 1936, the airport was opened for regular flights.[12] The village of Atarot was captured and destroyed by the Jordanian Arab Legion during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[citation needed]

From 1948 to the Six-Day War in June 1967, the airport was under Jordanian control, designated OJJR. Following the Six Day War, the Jerusalem airport was incorporated into the Jerusalem city municipal area and was designated LLJR.[citation needed]

In the 1970s and early 1980s, Israel invested considerable resources in upgrading the airport and creating the infrastructure for a full-fledged international airport but the international aviation authorities, bearing in mind that the airport was in lands captured in 1967 by Israel, would not allow international flights to land there. Thus the airport was only used for domestic flights and charter flights.[citation needed]

Due to security issues during the Second Intifada, the airport was closed to civilian air traffic in October 2000 and by July 2001 it was formally handed over to the Israel Defense Forces.[2]

In maps presented by Israel at the 2000 Camp David Summit, Atarot was included in the Israeli built-up area of Jerusalem.[12] This was rejected by the Palestinian delegation, which envisioned it as a national airport for the Palestinians. Yossi Beilin proposed that the airport be used jointly as part of an overall sharing of Jerusalem between Israel and Palestinian Authority, citing the successful model of Geneva International Airport, which is used by both Switzerland and France.[citation needed]

Israeli settlement planning

editA planning committee was scheduled to discuss on 6 December 2021, a proposal for 9,000 housing units. The site is between the Beit Hanina and Kafr Aqab, the "last free space for development left for Palestinians in the Jerusalem area."[13]

However, on 25 November 2021, under pressure from the Biden administration in the United States, Israel has shelved plans to redevelop Jerusalem airport site.[14]

Gallery

edit-

Atarot Airport/Jerusalem in 1961

-

An Arkia Airlines aircraft at Atarot Airport in 1968

-

The closed entrance to Atarot Airport in 2010, with a police jeep guarding

-

Jerusalem International Airport runway, 2023

-

Jerusalem International Airport tower, 2023

-

Atarot Airport, 1969

ICAO codes

editThe airport is sometimes shown with two different ICAO codes. The LL designator is used by ICAO for airports in Israel and OJ is the code for Jordan.[citation needed]

In popular culture

editAll the control tower scenes and the Algiers Airport terminal sequences of the Chuck Norris film The Delta Force, were filmed at Atarot Airport, with the terminal dressed in Arabic and French signs along with the addition of Algerian flags to act as Houari Boumedienne Airport.

The airport is depicted in the film World War Z as the main Israeli airport defended from a zombie epidemic. In reality all the Israeli scenes in the film were shot in Malta.[citation needed]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ RAF Operations 1918-38. W. Kimber. 1988. ISBN 9780718306717.

- ^ a b Blumenkrantz, Zohar (27 July 2001). "Jerusalem's Atarot Airport handed over to the IDF". Independent Media Review and Analysis Newsletter. Kokhaviv Publications. Archived from the original on 2001-12-22. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

The Airports Authority and the Defense Ministry recently signed an agreement on the army's use of the Atarot airport in Jerusalem. The Israel Defense Forces effectively took over the airport for its own use after it was shut down for civilian air traffic shortly after the start of the Intifada last October [2000]...

- ^ Palestine Studies, Gateway to the World-The Golden Age of Jerusalem Airport, 1948–67

- ^ Eldad Brin, 'Gateway to theWorld: The Golden Age of Jerusalem Airport, 1948–67' in The Jerusalem Quarterly no. 85, Spring 2021, p.74

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2016-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Derfner, Larry (2001-01-23). "An Intifada Casualty Named Atarot". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ An Empire in the Holy Land: Historical Geography of the British Administration of Palestine, 1917–1929 Gideon Biger, St. Martin's Press and Magnes Press, New York & Jerusalem, 1994, p. 152

- ^ Oren-Nordheim, Michael; Kark, Ruth (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800–1948. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0814329098.[page needed]

- ^ a b Houk, Marian (Autumn 2008). "Atarot and the Fate of the Jerusalem Airport". The Applied Research Institute-Jerusalem. Institute of Jerusalem Studies. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- ^ "Israel Advances Thousands of Housing Units in East Jerusalem as Biden Remains Silent". Haaretz.

- ^ "Israel backs off housing project at Jerusalem's Atarot airport site amid US pressure". The Times of Israel.

External links

edit- Media related to Jerusalem airport at Wikimedia Commons