Johannes Hevelius[note 1][note 2] (in German also known as Hevel; Polish: Jan Heweliusz; 28 January 1611 – 28 January 1687)[1] was a councillor and mayor of Danzig (Gdańsk) , in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[2] As an astronomer, he gained a reputation as "the founder of lunar topography",[1] and described ten new constellations, seven of which are still used by astronomers.[3]

Johannes Hevelius | |

|---|---|

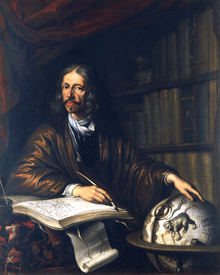

Portrait by Daniel Schultz | |

| Born | 28 January 1611 Danzig (Gdańsk), Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| Died | 28 January 1687 (aged 76), Danzig, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| Alma mater | Leiden University |

| Known for | Lunar topography |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | jurisprudence, astronomy, brewing |

Etymology

editAccording to the Polish Academy of Sciences (1975) the origin of the name goes back to the surname Hawke, a historical alternative spelling for the English word hawk, which changed into Hawelke or Hawelecke.[4] In Poland he is known as Jan Heweliusz.[5] Other versions of the name include Hewel,[6] Hevel, Hevelke[7] or Hoefel,[8] Höwelcke, Höfelcke.[9] According to Feliks Bentkowski (1814), during his early years he also signed as Hoefelius.[10] Along with the Latinized version of his name, Ludwig Günther-Fürstenwalde (1903) also reports Hevelius's signature as Johannes Höffelius Dantiscanus in 1631 and Hans Höwelcke in 1639.[11]

Early life

editHevelius's father was Abraham Hewelke (1576–1649), his mother Kordula Hecker (1576–1655). They were German-speaking Lutherans,[12] wealthy brewing merchants of Bohemian origin. As a young boy, Hevelius was sent to Gądecz (Gondecz) where he studied the Polish language.[13]

Hevelius brewed the famous Jopen beer, which also gave its name to the "Jopengasse"/"Jopejska" Street,[14][15] after 1945 renamed as Piwna Street (Beer Street),[16] where St. Mary's Church is located.

After gymnasium (secondary school), where he was taught by Peter Crüger, Hevelius in 1630 studied jurisprudence at Leiden, then travelled in England and France, meeting Pierre Gassendi, Marin Mersenne and Athanasius Kircher. In 1634 he settled in his native town, and on 21 March 1635 married Katharine Rebeschke, a neighbour two years younger who owned two adjacent houses. The following year, Hevelius became a member of the beer-brewing guild, which he led from 1643 onwards.[citation needed]

Astronomy

editThroughout his life, Hevelius took a leading part in municipal administration, becoming town councillor in 1651; but from 1639 on, his chief interest was astronomy. In 1641 he built an observatory on the roofs of his three connected houses, equipping it with splendid instruments, ultimately including a large Keplerian telescope of 46 m (150 ft) focal length,[1] with a wood and wire tube he constructed himself. This may have been the longest "tubed" telescope before the advent of the tubeless aerial telescope.[17]

The observatory was known by the name Sternenburg[7][18] (Latin: Stellaeburgum; Polish: Gwiezdny Zamek) or "Star Castle".[19] Polish Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga visited this private observatory on 29 January 1660. As a subject of the Polish kings, Hevelius enjoyed the patronage of four consecutive kings of Poland,[20] and his family was raised to the position of nobility by the King of Poland John II Casimir in 1660, who previously visited his observatory in 1659.[21] While the noble status was not ratified by the Polish Sejm Hevelius's coat of arms includes the distinctive Polish royal crown.[22] The Polish King John III Sobieski who regularly visited Hevelius numerous times in years 1677–1683 released him from paying taxes connected to brewing and allowed his beer to be sold freely outside the city limits.[23] In May 1679 the young Englishman Edmond Halley visited him as emissary of the Royal Society, whose fellow Hevelius had been since 1664. The Royal Society considers him one of the first German fellows.[24] Małgorzata Czerniakowska (2005) writes that "Jan Heweliusz was the first Pole to be inducted into the Royal Society in London. This important event took place on 19th March 1664".[25] Hevelius considered himself as being citizen of the Polish world (civis Orbis Poloniae)[26] and stated in a letter dated from 9 January 1681 that he was Civis orbis Poloni, qui in honorem patriae suae rei Literariae bono tot labores molestiasque, absit gloria, cum maximo facultatum suarum dispendio perduravit, i.e. "citizen of Polish world who, for glory of his country and for the good of science, worked so much, and while not boasting much, executed his work with most effort per his abilities".[27][28]

Halley had been instructed by Robert Hooke and John Flamsteed to persuade Hevelius to use telescopes for his measurements, yet Hevelius demonstrated that he could do well with only quadrant and alidade. He is thus considered the last astronomer to do major work without the use of a telescope.[29]

Hevelius made observations of sunspots, 1642–1645, devoted four years to charting the lunar surface, discovered the Moon's libration in longitude, and published his results in Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio (1647), a work which entitles him to be called "the founder of lunar topography".[1]

He discovered four comets, in 1652, 1661 (probably Ikeya-Zhang), 1672 and 1677. These discoveries led to his thesis that such bodies revolve around the Sun in parabolic paths.

A complex halo phenomenon was observed by many in the city on 20 February 1661, and was described by Hevelius in his Mercurius in Sole visus Gedani the following year.

Katharine, his first wife, died in 1662, and a year later Hevelius married Elisabeth Koopmann, the young daughter of a merchant family. The couple had four children. Elisabeth supported him, published two of his works after his death, and is considered the first female astronomer.

His observatory, instruments and books were destroyed by fire on 26 September 1679. The catastrophe is described in the preface to his Annus climactericus (1685). He promptly repaired the damage enough to enable him to observe the great comet of December 1680.[1] He named the constellation Sextans in memory of this lost instrument.

In late 1683, in commemoration of the victory of Christian forces led by Polish King John III Sobieski at the Battle of Vienna, he invented and named the constellation Scutum Sobiescianum (Sobieski's Shield), now called Scutum. This constellation first occurred publicly in his star atlas Firmamentum Sobiescianum, which was printed in his own house at lavish expense, and he himself engraved many of the printing plates.[1]

His health had suffered from the shock of the 1679 fire and he died on his 76th birthday, 28 January 1687.[1] Hevelius was buried in St. Catherine's Church in his hometown.

Descendants of Hevelius live in Urzędów in Poland where they support local astronomy enthusiasts.[30]

Works

edit- Selenographia (1647)

- De nativa Saturni facie ejusque varis Phasibus (1656)

- Historiola Mirae (1662), in which he named the periodic variable star Omicron Ceti "Mira", or "the Wonderful"

- Mercurius in Sole visus Gedani (1662), principally on the transit of Mercury, but containing chapters on many other observations

- Prodromus cometicus (1665)

- Cometographia (1668)[1]

- Machina coelestis (first part, 1673), containing a description of his instruments; the second part (1679) is extremely rare, nearly the whole issue having perished in the conflagration of 1679.[1] Hevelius's description of his "naked eye" observation method in the first part of this work led to a dispute with Robert Hooke who claimed observations without telescopic sights were of little value.[31]

- Annus climactericus, sive rerum uranicarum observationum annus quadragesimus nonus at Google Books (1685), describes the fire of 1679, and includes observations made by Hevelius on the variable star Mira

- Prodromus Astronomiae (c. 1690) an unfinished work posthumously published by Johannes wife Catherina Elisabetha Koopman Hevelius in three books including:[32][33]

- Prodromus, preface and unpublished observations

- Catalogus Stellarum Fixarum (dated 1687), catalog of 1564 stars

- Firmamentum Sobiescianum sive Uranographia (dated 1687), an atlas of constellations, 56 sheets, corresponding to his catalog,[1] contains seven new constellations delineated by him which are still in use (plus some now considered obsolete):

- Canes Venatici, Lacerta, Leo Minor, Lynx, Scutum, Sextans, and Vulpecula.

- Obsolete: Cerberus, Mons Maenalus, and Triangulum Minus.

See also

edit- Polish Navy Ship ORP Heweliusz

- Polish ferry MS Jan Heweliusz, which sank in 1993

- Hevelius (crater), Moon crater

- 5703 Hevelius, asteroid

- List of largest optical telescopes historically

- IH Cassiopeiae, a star designation used with some frequency, from his star map

- Heweliusz, a Polish optical astronomy satellite launched in 2014 as part of the Bright-star Target Explorer (BRITE) programme

Notes

edit- ^

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

- "Britannica". Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Bakich, Michael (2000). The Cambridge planetary handbook. Cambridge University Press. p. 255. ISBN 9780521632805. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Watson, Fred (2007). Stargazer: the life and times of the telescope. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781741763928. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Kanas, Nick (2007). Star maps: history, artistry, and cartography. Springer. ISBN 9780387716688. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Biagioli, Mario (2006). Star Galileo's instruments of credit: telescopes, images, secrecy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226045627. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Scalzi, John (2003). Star The rough guide to the universe. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781858289397. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Lankford, John (1997). History of astronomy: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 260. ISBN 9780815303220. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

- Daintith, John; Mitchell, Sarah; Tootill, Elizabeth; Gjertsen, D. (1994). Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Vol. 1. CRC Press. p. 414. ISBN 9780750302876. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Bakich, Michael E. (1995). The Cambridge guide to the constellations. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780521449212. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

Hevelius german.

- Watson, Fred (2004). Stargazer: The life and times of the telescope. Allen & Unwin. p. 32. ISBN 1-86508-658-4. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Ramamurthy, G. (2005). Biographical Dictionary of Great Astronomers. Sura Books. p. 103. ISBN 9788174786975. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Clerke, Agnes Mary (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). p. 416.

- Letters of the Royal Society

- "The Galileo Project". Rice University. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Clerke, Agnes Mary (1911). "Hevelius, Johann". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 416–417.

- ^ Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, 1998, p. 124, ISBN 0-415-16112-6 Google Books

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Star Tales". Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ^ Historia astronomii w Polsce: vol. 1 1975. Jerzy Dobrzycki, Eugeniusz Rybka, Polska Akademia Nauk. (Pracownia Historii Nauk ścisłych), page 256. OCLC 2776864

- ^ Older spellings include also Jan Hewelijusz and Jan Hefel, according to Samuel Orgelbrand. ed. 1884. Encyklopedyja powszechna S. Orgelbranda:nowe stereotypowe odbicie, vols 5-6 page 243. OCLC 17568522

- ^ Ushakov, Igor (2007). Histories of Scientific Insights. Lulu.com. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4303-2849-0.

- ^ a b Vaquero, José M.; Vázquez, Manuel (2009). The sun recorded through history. Springer. p. 126. ISBN 9780387927909.

- ^ Gomulicki, Wiktor Teofil (1978). Pieśń o Gdańsku (in Polish). Wydaw Morskie. p. 80.

- ^ Lawaty, Andreas; Domańska, Anna (2000). Deutsch-polnische Beziehungen in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German). Deutsches Polen-Institut. p. 998. ISBN 9783447042437.

- ^ Bentkowski, 1814. Historya literatury polskiey: wystawiona w spisie dzieł drukiem ogłoszonych, page 321.

- ^ Ludwig Günther-Fürstenwalde, "Johannes Hevelius: Ein Lebensbild aus dem XVII. Jahrhundert", Himmel und Erde: Illustrierte naturwissenschaftliche Monatsschrift, 15 (1903), 529–542.

- ^ "The Galileo Project". Rice University. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Libri Gedanenses, Tomy 23-24, Polska Akademia Naukowa Biblioteka Gdańska Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, page 127, 2005.

- ^ Stanisław Kutrzeba, Gdańsk przeszlość i teraźniejszość, Wydawnictwo Zakladu Narodowego im. Osslińskich, page 366, 1928: "jedna strona zamyka ulicę Jopejską". OCLC 14021052

- ^ Jan Kilarski, Gdańsk, Wydawnictwo Polskie, page 46, 1937. OCLC 26021672

- ^ Friedrich, Jacek (2010). Neue Stadt in altem Glanz - Der Wiederaufbau Danzigs 1945-1960 (in German). Böhlau. p. 43. ISBN 978-3-412-20312-2.

- ^ M1 Henry C. King, Harold Spencer Jones - The history of the telescope, page 53

- ^ Lachièze-Rey, Marc; Luminet, Jean-Pierre (2001). Celestial Treasury: from the music of the spheres to the conquest of space. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-521-80040-4.

King, Henry C. (2003). The history of the telescope. Courier Dover publ. p. 53. ISBN 0-486-43265-3.

Manly, Peter L. (1995). Unusual telescopes. Cambridge University Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-521-48393-X.

Pendergrast, Mark (2003). Mirror mirror. Basic Books. p. 96. ISBN 9780465054701.

Moore, Patrick (2002). Astronomy encyclopedia. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780195218336. - ^ Gdański dom Jana Heweliusza Archived 2 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hippolit Skimborowicz: Żywot i prace Jana Hewelinsza gdańszczanina żyjacego pod panowaniem czterech królów polskich, Warszawa 1860. OCLC 253951432

- ^ Kwartalnik historii kultury materialnej, Tom 39, Instytut Historii Kultury Materialnej 1991 (Polska Akademia Nauk), page 159.

- ^ On the 300th anniversary of the death of Johannes Hevelius: book of The International Scientific Session, Robert Glȩbocki, Andrzej Zbierski, International Scientific Session, Ossolineum, The Polish Academy of Sciences, page 56, 1992.

- ^ Międzynarodowy Rok Heweliusza 1987: dokumentacja obchodów trzechsetnej rocznicy śmierci Jana Heweliusza (1687-1987), page 10, 1990 Zakład Narodowy im Ossolińskich.

- ^ da Costa Andrade, Edward Neville (1960). A brief history of the Royal Society. Royal Society. p. 24. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ "Jan Heweliusz i Royal Society Małgorzata Czerniakowska". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Wandycz, Piotr Stefan (2001). The price of freedom: a history of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 3-406-36798-4.

- ^ Rocznik gdański, Tom 65,Gdańskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, Wydział Nauk Społecznych i Humanistycznych,page 135, 2005

- ^ Aleksander Birkenmajer, Etudes d'histoire des sciences en Pologne: Choix d'articles par les rédacteurs, Ossolineum, page 15, 1972. OCLC 758078

- ^ Daintith, John, Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, CRC Books, 1994 ISBN 0-7503-0287-9 at Google Books

- ^ Potomkowie Jana Heweliusza Archived 1 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ J J O'Connor and E F Robertson, Johannes Hevelius, gap-system.org Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The United States Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command (NMOC), Hevelius - Prodromus astronomiae". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Nick Kanas, Star maps: history, artistry, and cartography, page 164

External links

edit- Galileo Project on Hevelius

- Project to publish the correspondence of Hevelius at the International Academy of the History of Science

- Electronic facsimile-editions of the rare book collection at the Vienna Institute of Astronomy

- (in Polish) Jan Heweliusz - Gdańszczanin Tysiąclecia Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Prodromus astronomiae - in digital facsimile:

- Johann Hevelius - Forgotten Pioneer of the Pendulum Clock

- Uranographia, Danzica 1690 da www.atlascoelestis.com

- Hevelius's new constellations

- Johannes Hevelius letter to Johann Philipp von Wurtzelbau, MSS 494 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University

- Johannes Hevelius's correspondence on the Paris Observatory digital library

- Works by Johannes Hevelius in digital library Polona

- Tautschnig, Irina (2022). "Constructing Authority in the Paratext: The Poems to Johannes Hevelius' Selenographia". Perspectives on Science. 30 (6): 1005–1041. doi:10.1162/posc_a_00569. S2CID 250537021. Project MUSE 872578.