James Henry Schmitz (October 15, 1911 – April 18, 1981) was a German-American science fiction writer.[1]

James H. Schmitz | |

|---|---|

Schmitz with his dog. | |

| Born | James Henry Schmitz October 15, 1911 Hamburg, Germany |

| Died | April 18, 1981 (aged 69) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Short story writer, novelist |

| Years active | 1943–74 |

| Spouse | Betty Mae Chapman Schmitz |

Early life

editSchmitz was born in Hamburg, Germany to American parents[1] and was educated at a Realgymnasium in Hamburg,[2] and grew up speaking both English and German. The family spent World War I in the United States, then returned to Germany.[3]

Education and early career

editSchmitz traveled to Chicago in 1930 to go to business school, then switched to a correspondence course in journalism. Unable to find a job because of the Great Depression, he returned to Germany to work with his father's company.[4] Schmitz lived in various German cities, where he worked for the International Harvester Company,[2] until his family left shortly before World War II broke out in Europe.[2][5]

Writing career

editSchmitz wrote mostly short stories, which sold chiefly to Galaxy Science Fiction and Astounding Science-Fiction (which later became Analog Science Fiction and Fact). Gale Biography in Context called him "a craftsmanlike writer who was a steady contributor to science fiction magazines for over 20 years."[2]

Schmitz is best known as a writer of "space opera", and for his strong female characters (such as Telzey Amberdon and Trigger Argee) who did not conform to the "damsel in distress" stereotype typical of science fiction of the time.[6]

His first published story was "Greenface", published in August 1943 in Unknown.[7]

Most of his works are part of the "Hub" series and feature characters with telepathy. However, the novel that "is usually thought of as Schmitz's best work"[6] is The Witches of Karres, concerning juvenile "witches" with genuine psi-powers and their escape from slavery. The Witches of Karres was nominated for a Hugo Award. In recent years, his novels and short stories have been republished by Baen Books, edited and with notes by Eric Flint.

In an introductory essay comparing Schmitz with contemporary author A. E. van Vogt, Gardner Dozois wrote, "Although he lacked van Vogt's paranoid tension and ornately Byzantine plots, the late James H. Schmitz was considerably better at people than van Vogt was, crafting even his villains as complicated, psychologically complex, and non-stereotypical characters, full of surprising quirks and behaviors that you didn't see in a lot of other Space Adventure stuff."[6]

Dozois added:

And his universes, although they come with their own share of monsters and sinister menaces, seem as if they would be more pleasant places to live than most Space Opera universes, places where you could have a viable, ordinary, and decent life once the plot was through requiring you to battle for existence against some Dread Implacable Monster; Schmitz even has sympathy for the monsters, who are often seen in the end not to be monsters at all, but rather creatures with agendas and priorities and points-of-view of their own, from which perspectives their actions are justified and sometimes admirable—a tolerant attitude almost unique amidst the Space Adventure tales of the day, most of which were frothingly xenophobic.[6]

John Clute writes in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction,

From 1949, when "Agent of Vega" appeared in ASF as the first of 4 stories later assembled as Agent of Vega (collection of linked stories 1960), he regularly produced the kind of tale for which he remains most warmly remembered: Space Opera adventures, several featuring female Heroes depicted with minimum recourse to their "femininity" – they perform their active tasks, and save the Universe when necessary, in a manner almost completely free of sexual role-playing clichés. Most of his best work shares a roughly characterized common background, a Galaxy inhabited by humans and aliens with room for all and numerous opportunities for discoveries and reversals that carefully fall short of threatening the stability of that background. Many of his stories, as a result, focus less on moments of Conceptual Breakthrough than on the pragmatic operations of teams and bureaux involved in maintaining the state of things against criminals, monsters and unfriendly species; in this they rather resemble the tales of Murray Leinster, though they are more vigorous and less inclined to punish adventurousness.[7]

Greg Fowlkes, editor-in-chief of Resurrected Press, said, "During the 50s and 60s "Space Opera" and James H. Schmitz were almost synonymous. He was famous for his tales of interstellar secret agents and galactic criminals, and particularly for heroines such as Telzey Amberdon and Trigger Argee. Many of these characters had enhanced "psionic" powers that let them use their minds as well as their weapons to foil their enemies. All of them were resourceful in the best heroic tradition."[8]

In an essay in the anthology The Good Old Stuff (1998), Dozois laments that the book Agent of Vega is "long out-of-print, alas, but one which – if you can find it – delivers as pure a jolt of Widescreen Space Opera Sense of wonder as can be found anywhere." However, the website Free Speculative Fiction Online freely offers Agent of Vega, along with several of Schmitz's other stories, including "Greenface", "Balanced Ecology", "Lion Loose", "Goblin Night", and many more.

Schmitz wrote the introduction to the concordance The Universes of E. E. Smith.[9]

Legacy

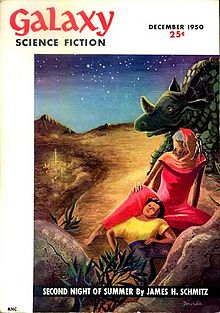

editGardner Dozois has said, in prefacing the Schmitz tale "The Second Night of Summer",[10] in which humans on the planet Noorhut face an attack from aliens and are, unbeknownst to themselves, saved by the actions of a single woman with psi powers, Granny Wannattel, with the sole help of a friendly alien she calls her pony:

Schmitz was decades ahead of the curve in his portrayal of female characters—years before the Women's Movement of the '70s would come along to raise the consciousness of SF writers (or attempt to), Schmitz was not only frequently using women as the heroines in swashbuckling tales of interplanetary adventure—itself almost unheard of at the time—but he was also treating them as the total equal of the male characters, every bit as competent and brave and smart (and ruthless, when needs be), without saddling them with any of the "female weaknesses"—like an inclination to faint or cower under extreme duress, and/or seek protection behind the muscular frame of the Tough Male Hero) that would mar the characterization of women by some writers for years to come. (The Schmitz Woman, for instance, is every bit as tough and competent as the Heinlein Woman—who, to be fair, isn't prone to fainting in a crisis either—but without her annoying tendency to think that nothing in the universe is as important as marrying Her Man and settling down to have as many babies as possible.)[6]

With his popular equality-between-the-sexes fiction, Schmitz eased the way for later writers such as Joanna Russ, James Tiptree, Jr., Kit Reed, Connie Willis, Sheri S. Tepper, and other science fiction authors who used female protagonists and feminine point-of-view more than half the time. Of "The Second Night of Summer", Dozois went on to write, "the hero of the piece is not only a woman, but an old woman ... a choice that most adventure writers wouldn't even make now, in 1998, let alone in 1950, which is when Schmitz made it!"[6]

Mercedes Lackey places her first meeting with science fiction at age 10 or 11, when she happened to pick up her father's copy of James H. Schmitz's Agent of Vega.

Personal life

editDuring World War II, Schmitz served as an aerial photographer in the Pacific for the United States Army Air Forces. After the war, he took residence in California where he and his brother-in-law managed a business which manufactured trailers until they ended the business in 1949.[5][3] Schmitz died of congestive lung failure[5] in 1981 after a five-week stay in hospital in Los Angeles. He was survived by his wife, Betty Mae Chapman Schmitz.

Short works

editListed chronologically, with month and year of publication, as well as the magazine, listed in parentheses.

1940s

edit- "Greenface" (August 1943, Unknown)

- "Agent of Vega" (July 1949, Astounding)

- "The Witches of Karres" (Novella, December 1949, Astounding)

1950s

edit- "The Truth About Cushgar" (November 1950, Astounding)

- "The Second Night of Summer" (December 1950, Galaxy Science Fiction)

- "Space Fear" (March 1951, Astounding)

- "Captives of the Thieve Star" (May 1951, Planet Stories)

- "The End of the Line" (July 1951, Astounding)

- "The Altruist" (September 1952, Galaxy Science Fiction)

- "We Don't Want Any Trouble" (June 1953, Galaxy Science Fiction)

- "Caretaker" (July 1953, Galaxy Science Fiction)

- "The Vampirate" (December 1953, Science-Fiction Plus)

- "Grandpa" (February 1955, Astounding)

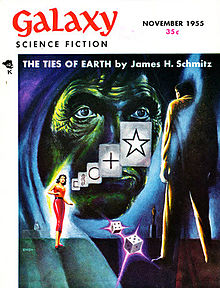

- "The Ties of Earth" (November 1955, Galaxy Part 1)(January 1956, Galaxy part 2)

- "Sour Note on Palayata" (November 1956, Astounding)

- "The Big Terrarium" (May 1957, Saturn)

- "Harvest Time" (September 1958, Astounding)

- "Summer Guests" (September 1959, Worlds of If)

1960s

edit- "The Illusionists" (retitle of Space Fear, 1960, Agent of Vega)

- "Gone Fishing" (May 1961, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Lion Loose..." (October 1961, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "The Star Hyacinths" (December 1961, Amazing Stories)

- "An Incident on Route 12" (January 1962, Worlds of If)

- "Swift Completion" (March 1962, Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine)

- "Novice" (June 1962, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "The Other Likeness" (July 1962, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Rogue Psi" (August 1962, Amazing Stories)

- "Watch the Sky" (August 1962, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "These Are the Arts" (September 1962, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction)

- "The Winds of Time" (September 1962, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Left Hand, Right Hand" (November 1962, Amazing Stories)

- "Beacon to Elsewhere" (April 1963, Amazing Stories)

- "Oneness" (May 1963, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Ham Sandwich" (June 1963, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Undercurrents" (in two parts, May and June 1964, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Clean Slate" (September 1964, Amazing Stories)

- "The Machmen" (September 1964, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "A Nice Day for Screaming" (January 1965, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Planet of Forgetting" (February 1965, Galaxy Science Fiction)

- "The Pork Chop Tree" (February 1965, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Balanced Ecology" (March 1965, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Goblin Night" (April 1965, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Trouble Tide" (May 1965, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Research Alpha" (July 1965, Worlds of If)

- "Sleep No More" (August 1965, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Space Master" (1965, New Writings in SF 3)

- "The Tangled Web" (retitle of The Star Hyacinths, 1965, A Nice Day for Screaming and Other Tales of the Hub)

- "Faddist" (January 1966, Bizarre Mystery Magazine)

- "The Searcher" (February 1966, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "The Witches of Karres" (Novel, 1966)

- "The Tuvela" (in two parts, September and October 1968, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Where the Time Went" (November 1968, Worlds of If)

- "The Custodians" (December 1968, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Just Curious" (December 1968, Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine)

- "Attitudes" (February 1969, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction)

- "Would You?" (December 1969, Fantastic)

1970s

edit- "Resident Witch" (May 1970, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Compulsion" (June 1970, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "The Telzey Toy" (January 1971, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Company Planet" (May 1971, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Glory Day" (June 1971, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Poltergeist" (July 1971, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "The Lion Game" (in two parts, August and September 1971, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Child of the Gods" (March 1972, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "The Symbiotes" (September 1972, Analog Science Fiction and Science Fact)

- "Crime Buff" (August 1973, Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine)

- "One Step Ahead" (April 1974, Worlds of If)

- "Aura of Immortality" (June 1974, Worlds of If)

2000s

edit- "Blood of Nalakia" (retitle of The Vampirate, 2000, Telzey Amberdon)

- "Ti's Toys" (retitle of The Telzey Toy, 2000, T'nT: Telzey & Trigger)

- "Forget It" (retitle of Planet of Forgetting, January 2001, Trigger & Friends)

Collections

editListed by title, with chronological publishing list.

- Agent of Vega

- Includes: Agent of Vega; The Illusionists; The Truth About Cushgar; The Second Night of Summer

- Hardcover, 1960, Gnome Press, listed on cover as "James A. Schmitz"

- Paperback, June 1962, Permabook

- Paperback, June 1964, Mayflower

- Paperback, 1973, Tempo Books/Grosset & Dunlap

- Paperback, 1982, Ace Books

- Agent of Vega & Other Stories

- Includes: Agent of Vega; The Illusionists; The Second Night of Summer; The Truth About Cushgar; The Custodians; Gone Fishing; The Beacon to Elsewhere; The End of the Line; Watch the Sky; Greenface; Rogue Psi.

- Paperback, November 2001, Baen Books

- The Best of James H. Schmitz

- Includes: Grandpa; Lion Loose...; Just Curious; The Second Night of Summer; Novice; Balanced Ecology; The Custodians; Sour Note on Palayata; Goblin Night.

- Hardcover, 1991, NESFA Press

- Eternal Frontier

- Includes: The Big Terrarium; Summer Guests; Captives of the Thieve-Star; Caretaker; One Step Ahead; Left Hand, Right Hand; The Ties of Earth; Spacemaster; The Altruist; Oneness; We Don't Want Any Trouble; Just Curious; Would You?; These Are the Arts; Clean Slate; Crime Buff; Ham Sandwich; Where the Time Went; An Incident on Route 12; Swift Completion; Faddist; The Eternal Frontiers.

- Paperback, September 2002, Baen Books

- The Hub: Dangerous Territory

- Includes: The Searcher; Grandpa; Balanced Ecology; A Nice Day for Screaming; The Winds of Time; The Machmen; The Other Likeness; Attitudes; Trouble Tide; The Demon Breed.

- Paperback, 2001, Baen Books

- The Lion Game

- Includes: Goblin Night; Sleep No More; The Lion Game.

- Paperback, 1973, DAW Books

- Hardcover, 1976, Sidgwick & Jackson

- Paperback, 1979, Hamlyn

- Paperback, 1982, Ace Books

- A Nice Day for Screaming and Other Tales of the Hub

- Includes: Balanced Ecology; A Nice Day for Screaming; The Tangled Web; The Machmen; The Other Likeness; The Winds of Time.

- Hardcover, 1965, Chilton

- A Pride of Monsters

- Telzey Amberdon

- Includes: Novice; Undercurrents; Poltergeist; Goblin Night; Sleep No More; The Lion Game; Blood of Nalakia; The Star Hyacinths.

- Paperback, April 2000, Baen Books

- The Telzey Toy

- Includes: The Telzey Toy; Resident Witch; Compulsion; Company Planet.

- Paperback, 1973, DAW Books

- Hardcover, 1976, Sidgwick & Jackson

- Hardcover, 1978, Sidgwick & Jackson, in a 3-in-1 collection titled Special 24

- Paperback, 1982, Ace Books

- Paperback, 1983, Hamlyn

- The Universe Against Her

- Includes: Novice; Undercurrents.

- Paperback, 1964, Ace Books

- Paperback, 1979, Ace Books

- Hardcover, 1981, Gregg Press

- T'nT: Telzey & Trigger

- Includes: Company Planet; Resident Witch; Compulsion (includes The Pork Chop Tree as prolog); Glory Day; Child of the Gods; Ti's Toys; Symbiotes.

- Paperback, July 2000, Baen Books

- Trigger & Friends

- Includes: Lion Loose; Harvest Time; Forget It; Aura of Immortality; Legacy; A Sour Note on Palayata.

- Paperback, January 2001, Baen Books

- The Winds of Time

- Includes: An Incident on Route 12; Watch the Sky; The Winds of Time; Lion Loose.

- Paperback, February 2008, Wildside Press

Novels

editListed by title, with chronological publishing list.

- The Demon Breed (retitle of The Tuvela)

- Hardcover, 1968, Ace Books/SFBC

- Paperback, 1968, Ace Books

- Hardcover, 1969, MacDonald

- Hardcover, 1971, UK SFBC/Newton Abbot

- Paperback, 1974, Orbit Books

- Paperback, 1979, Ace Books/SFBC

- Paperback, 1981, Ace Books

- The Eternal Frontiers

- Hardcover, 1973, G. P. Putnam's Sons

- Paperback, 1973, Berkley Books

- Hardcover, 1974, Sidgwick & Jackson

- Hardcover, 1976, Sidgwick & Jackson (in a 3-in-1 compilation titled Special 18)

- Legacy (retitle of A Tale of Two Clocks, paperback, 1979, Ace Books) (available from gutenberg)

- A Tale of Two Clocks

- Hardcover, 1962, Torquil Books/SFBC

- Paperback, 1965, Belmont

- The Witches of Karres

- Hardcover, 1966, Chilton

- Paperback, 1966 (twice), Ace Books

- Paperback, 1977, Ace Books

- Paperback, 1981, Ace Books

- Paperback, 1988, Gollancz

- Hardcover, 1992, Baen Books/SFBC

Related books

edit- The Wizard of Karres, by Mercedes Lackey, Eric Flint and Dave Freer, 2004

- This is a sequel of The Witches of Karres which follows the continuing adventures of Captain Pausert, Goth, and the Leewit.

- The Sorceress of Karres, by Eric Flint and Dave Freer, 2010

- This is a sequel of The Wizard of Karres which follows the continuing adventures of Captain Pausert, Goth, and the Leewit.

- The Shaman of Karres, by Eric Flint and Dave Freer, 2020

- This is a sequel of The Sorceress of Karres which follows the continuing adventures of Captain Pausert, Goth, and the Leewit.

References

edit- ^ a b Von Ruff, Al. "James H. Schmitz – Summary Bibliography". isfdb.org. Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "James H(enry) Schmitz". Gale Biography in Context. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Best of James H. Schmitz". New England Science Fiction Association. June 24, 2003. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ "James H. Schmitz [sidebar]". SF Site. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c Scheick, Robyn. "Schmitz, James H. (1911–1981)". Millersville University Archives, Millersville University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Dozois, Gardner (1999). The Good Stuff: Adventure SF in the Grand Tradition. New York: SFBC. p. 45.

- ^ a b Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). "Schmitz, James H(enry)". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. pp. 1057–1058. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- ^ Fowlkes, Greg (2010). "James H. Schmitz Resurrected: Selected Stories of James H. Schmitz – Editor's Notes". Resurrected Press. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ Ellik, Ron; Bill Evans (1966). "The Universes of E. E. Smith". New England Science Fiction Association. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ Schmitz, James H. (1950). "The Second Night of Summer [full text]". Free Speculative Fiction Online. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

External links

edit- James H. Schmitz at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- James H. Schmitz obituary

- The James H. Schmitz Encyclopedia

- SciFan database

- Major characters, with illustrations[permanent dead link]

- Works by James H. Schmitz at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James H. Schmitz at the Internet Archive

- Works by James H. Schmitz at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- James H. Schmitz's online fiction at Free Speculative Fiction Online