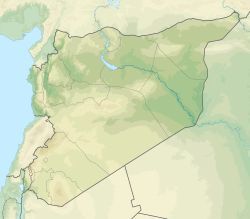

Jableh (Arabic: جَبْلَةٌ; Ǧabla, also spelt Jebleh, Jabala, Jablah, Gabala or Gibellum) is a Mediterranean coastal city in Syria,[2] 25 km (16 mi) north of Baniyas and 25 km (16 mi) south of Latakia, with c. 80,000 inhabitants (2004 census). As Ancient Gabala it was a Byzantine (arch)bishopric and remains a Latin Catholic titular see. It contains the tomb and mosque of Ibrahim Bin Adham, a legendary Sufi mystic who renounced his throne of Balkh and devoted himself to prayers for the rest of his life.[3]

Jableh

جَبْلَةٌ Gabala | |

|---|---|

General view of city and port • Roman Amphitheater • Al-Baath Stadium • Entrance of Roman Theater • Landscape of Jableh • Port | |

| Nickname: Mount of the Soul (Arabic: جَبْلَة ٱلرّوح) | |

| Coordinates: 35°21′N 35°55′E / 35.350°N 35.917°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Latakia Governorate |

| District | Jableh District |

| Subdistrict | Jableh Subdistrict |

| Elevation | 16 m (52 ft) |

| Population (2004 census) | |

• Total | 80,000[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Arabic: جَبْلَاوِي, romanized: Jablawi |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code(s) | Country code: 963 City code: 41 |

| Geocode | C3585 |

| Climate | Csa |

History

editJableh has been inhabited since at least the second millennium BCE.[4] The city was part of the Ugaritic kingdom and was mentioned as "Gbʿly" in the archives of the city c. 1200 BC.[5] In antiquity Jableh (then called Gabala) was an important Hellenistic and then Roman city. One of the main remains of this period is a theatre, capable of housing c. 7,000 spectators. Near the seashores even older remains were found dating to the Iron Age or Phoenician Era.

The Jableh region was incorporated into the Islamic Empire with the conquest of Syria in 637–642. Between approximately 969 and 1081, however, much of the region returned under the control of the Byzantine Empire, until it was captured by Banu Ammar.[6][7] The Alawites began spreading in the area in the early eleventh century.[8]

In the medieval period, Jableh, then called Gibellum, was conquered by Tancred and the Genoese on 23 July 1109,[9] to be part of the Principality of Antioch, one of the Crusader States, until it was captured by Saladin in 1189 during the Third Crusade. One famous resident was Hugh of Jabala, the city's bishop, who reported the fall of Edessa to Pope Eugene III, and was the first person to speak of Prester John. Less than 1 kilometre (0.62 miles) from the city centre lies the ancient site of Gibala, today known as Tell Tweini. This city was inhabited from the third millennium BCE until the Persian period.

During the Mamluk period, there was still a "Kurdish" mosque in the city that had probably been founded by members of Saladin's entourage or army.[10] In 1318, a millenarian revolt of Alawites from the surrounding highlands resulted in an attack on Jableh before a Mamluk column sent from Tripoli was able to retake control. The famous Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited Jableh in 1326.[11]

In the Ottoman period (1516–1918), Jabala originally formed a sub-province (sancak) of the province of Tripoli before it was made its own sancak in 1547–1548.[12] The district (nahiye) of Jabala comprised approximately 80 villages in addition to Jableh itself, the majority of which were inhabited by Alawites.[13] In 1564, the province of Jableh was governed by the son of Janbulad ibn Qasim al-Kurdi, the sancak-beyi of Kilis. The city of Jableh gained special importance with the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus, which lies just 120 km directly offshore, in 1570. The governor and the qadi (judge) of Jableh received numerous orders from the Ottoman government to guard the area against Mediterranean pirates and rebel Alawites in the next decades.[14] The city and the province of Jableh became less important as Latakia rose in importance in the eighteenth century. At the end of the nineteenth century, the province of Jableh was divided into twenty new nahiyes.[15]

On May 23, 2016, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant claimed responsibility for four suicide bombings in Jableh, which had remained largely unaffected since the Syrian Civil War began in 2011. Purportedly targeting Alawite gatherings, the bombs killed over a hundred people. In Tartus, similarly insulated, another three bombers killed 48 people.[16]

In February 2023, a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Turkey and western Syria. It caused widespread destruction and fatalities. In Jableh, at least 283 people died, 173 were injured and 19 buildings collapsed.[17]

Economy

editThe majority of people in Jableh depend on agriculture for their income, people grow orange and lemon trees, olives, a large number of green houses for vegetables can be found in the country side. In the center of the city people work in trade and there are small factories in the city for cottons and for making orange juice, whilst most residents solely depend on retirement allowance, although Jableh's economy suffers due to barely any electricity times between neighborhoods, which affects water availability in the city.

Sports

editJableh Sporting Club is a football club based in Jableh, playing in the Al-Baath Stadium, which has a seating capacity of 10,000.

People

edit- Syrian pioneer of modern Arabic poetry Adunis.

- Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, a famous Islamic figure who organized attacks on the French in Syria and on the British and Jews in Palestine and the namesake of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas.

- The Boustani family.[18]

- Mohammad Zeitoun, a swimming champion whose story is featured in Zeitoun.

- Ali Maia, footballer

- Dr. Fayez Attaf, general surgeon who was known as 'The Poor People's Surgeon' in Jableh. He regularly paid the cost of operations of displaced and poor patients. He and his wife, neurologist Dr. Hala Saiid died in the February 2023 earthquake.[19]

Climate

editJableh has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa).

| Climate data for Jableh | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.5 (79.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

22.4 (72.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.5 (58.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 159 (6.3) |

130 (5.1) |

109 (4.3) |

50 (2.0) |

28 (1.1) |

4 (0.2) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

15 (0.6) |

52 (2.0) |

89 (3.5) |

190 (7.5) |

828 (32.6) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 14 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 81 |

| Source 1: World Weather Online | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate Data | |||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ http://www.cbssyr.sy/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf Population of Jableh at the Wayback Machine (archived 2022-03-20)

- ^ "Gabala". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Battuta, Abu `Abdullah Muhammad (1996). Gibb, Sir Hamilton (ed.). M1 Google Books, Travels In Asia And Africa, 1325-54. Asian Educational Services. p. 62. ISBN 81-206-0809-7.

- ^ Esber, Hawazan. "Small historical coastal cities: Urban development and freshwater resources". UNESCO. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ William A. Ward; Martha Joukowsky (1992). The Crisis years: the 12th century B.C.: from beyond the Danube to the Tigris. Kendall/Hunt. p. 113. ISBN 9780840371485.

- ^ Wiet 1960, p. 448.

- ^ Mallett 2014.

- ^ Winter 2016, p. 27–31, 45

- ^ Helmolt 1907, p. 377

- ^ Winter, Stefan (2009). "Les Kurdes de Syrie dans les archives ottomanes". Études Kurdes: 125–156.

- ^ Winter 2016, p. 61–67

- ^ Winter 2016, p. 88

- ^ Winter 2016, p. 95–107

- ^ Winter 2016, p. 111–118

- ^ Hartmann, Martin (1891). "Das Liwa el-Ladkije und die Nahije Urdu". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins: 161–218.

- ^ "IS blasts in Syria regime heartland kill more than 148". AFP. Channel NewsAsia. Archived from the original on 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ Dabin, B.; al-Jazaeri, R. (9 February 2023). "283 deaths 173 injuries in the earthquake in Jableh, Lattakia". Syrian Arab News Agency. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "History | Boustani Congress". 2020-11-30. Archived from the original on 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2023-12-09.

- ^ "هالة وفايز... الحب يلمع تحت الأنقاض".

Bibliography

edit- Helmolt, Hans Ferdinand (1907), The World's History: Central and northern Europe, The University of Michigan

- Mallett, Alex (2014). "ʿAmmār, Banū (Syria)". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24909. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Wiet, G. (1960). "ʿAmmār". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 448. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_0625. OCLC 495469456.

- Winter, Stefan (2016), A History of the Alawis: From Medieval Syria to the Turkish Republic, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691173894