John Weldon "J. J." Cale[1] (December 5, 1938 – July 26, 2013) was an American guitarist, singer, and songwriter. Though he avoided the limelight,[2] his influence as a musical artist has been acknowledged by figures such as Neil Young, Mark Knopfler, Waylon Jennings, and Eric Clapton, who described him as one of the most important artists in rock history.[3] He is one of the originators of the Tulsa sound, a loose genre drawing on blues, rockabilly, country, and jazz.

J.J. Cale | |

|---|---|

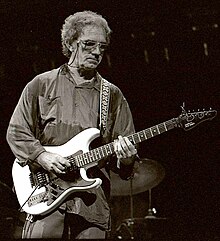

Cale in 2006 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Weldon Cale |

| Born | December 5, 1938 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 2013 (aged 74) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1958–2013 |

| Labels | |

| Website | jjcale |

In 2008, Cale and Clapton received a Grammy Award for their album The Road to Escondido.

Life and career

editEarly years

editCale was born on December 5, 1938, in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.[1] He was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and graduated from Tulsa Central High School in 1956. As well as learning to play the guitar he began studying the principles of sound engineering while still living with his parents in Tulsa, where he built himself a recording studio.[4] After graduation he was drafted into military service, studying at the Air Force Air Training Command in Rantoul, Illinois. Cale recalled, "I didn't really want to carry a gun and do all that stuff so I joined the Air Force and what I did is I took technical training and that's kind of where I learned a little bit about electronics."[5] Cale's knowledge of mixing and sound recording turned out to play an important role in creating the distinctive sound of his studio albums.[6]

Early musical career

editAlong with a number of other young Tulsa musicians, Cale moved to Los Angeles in late 1964, where he found employment as a studio engineer as well as playing at bars and clubs. Cale first tasted success that year when singer Mel McDaniel scored a regional hit with Cale's song "Lazy Me". He managed to land a regular gig at the increasingly popular Whisky a Go Go in March 1965,[7][8] where club co-owner Elmer Valentine rechristened Cale as J.J. Cale to avoid confusion with the John Cale in the Velvet Underground.[9] In 1966, while living in the city, he cut a demo single with Liberty Records of his songs "After Midnight" with "Slow Motion" as the B side.[10] He distributed copies of the single to his Tulsa musician friends living in Los Angeles, many of whom were successfully finding work as session musicians. "After Midnight" would go on to have long-term ramifications for Cale's career when Eric Clapton recorded the song and it became a Top 20 hit. Cale found little success as a recording artist. Not being able to make enough money as a studio engineer, he sold his guitar and returned to Tulsa in late 1967. There he joined a band with Tulsa musician Don White.

Rise to fame

editIn 1970, it came to his attention that Eric Clapton had recorded Cale's "After Midnight" on his debut album. Cale, who was languishing in obscurity at the time, had no knowledge of Clapton's recording until it became a radio hit in 1970. He recalled to Mojo magazine that when he heard Clapton's version playing on his radio, "I was dirt poor, not making enough to eat and I wasn't a young man. I was in my thirties, so I was very happy. It was nice to make some money."[11] Cale's version of "After Midnight" differs greatly from Clapton's frenetic version, which is itself based on Cale's own arrangement:

The history on that deal was, the original "After Midnight" I recorded was on Liberty Records on a 45-rpm, and it was fast. That was about 1967-68, maybe 69. I can't remember exactly. But that was the original "After Midnight", and that is what Clapton heard. If you listen to Eric Clapton's record, what he did was imitate that. No one heard that first version I made of it. I tried to give the thing away, until he cut it and made it popular. So, when I recorded the Naturally album Denny Cordell, who ran Shelter Records at the time, and I had already finished the album, he said, "John, why don't you put 'After Midnight' on there because that is what people recognize you for?" I said, "Well, I've already got that on Liberty Records, and Eric Clapton's already cut it, so if I'm going to do it again I'm going to do it slow.[12]

It was suggested to Cale that he should take advantage of this publicity and cut a record of his own. His first album, Naturally, released on October 25, 1971, established his style, described by Los Angeles Times writer Richard Cromelin as a "unique hybrid of blues, folk and jazz, marked by relaxed grooves and Cale's fluid guitar and iconic vocals. His early use of drum machines and his unconventional mixes lend a distinctive and timeless quality to his work and set him apart from the pack of Americana roots music purists."[13] His biggest U.S. hit single, "Crazy Mama", peaked at No. 22 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1972. In the 2005 documentary film To Tulsa and Back, Cale recounts the story of being offered the opportunity to appear on Dick Clark's American Bandstand to promote the song, which would have moved it higher on the charts. Cale declined when told he could not bring his band to the recording and would be required to lip-sync the words.[14]

Really was produced by Audie Ashworth, who would go on to produce Cale until 1983. Cale's second album further developed the "Tulsa sound" that he would become known for: a swampy mix of folk, jazz, shuffling country blues, and rock 'n' roll. Although his songs have a relaxed, casual feel, Cale, who often used drum machines and layered his vocals, carefully crafted his albums, explaining to Lydia Hutchinson in 2013, "I was an engineer, and I loved manipulating the sound. I love the technical side of recording. I had a recording studio back in the days when no one had a home studio. You had to rent a studio that belonged to a big conglomerate."[15] Cale often acted as his own producer / engineer / session player. His vocals, sometimes whispery, would be buried in the mix. He attributed his unique sound to being a recording mixer and engineer, saying, "Because of all the technology now you can make music yourself and a lot of people are doing that now. I started out doing that a long time ago and I found when I did that I came up with a unique sound."[16]

Although Cale would not have the success with his music that others would, the royalties from artists recording his songs would allow him to record and tour as it suited him. He scored another windfall when Lynyrd Skynyrd recorded "Call Me the Breeze" for their 1974 LP Second Helping. As he put it in an interview with Russell Hall, "I knew if I became too well known, my life would change drastically. On the other hand, getting some money doesn't change things too much, except you no longer have to go to work."[17] His third album Okie contains some of Cale's most recorded songs. In the same year of its release, Captain Beefheart recorded "I Got the Same Old Blues" (shortened to "Same Old Blues") for his Bluejeans & Moonbeams LP, one of the few non-originals to ever appear on a Beefheart album. The song would also be recorded by Eric Clapton, Bobby Bland, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Bryan Ferry. "Cajun Moon" was recorded by Herbie Mann on his 1976 album Surprises with vocals by Cissy Houston, by Poco on their album Cowboys & Englishmen, and by Randy Crawford on Naked and True (1995).

The 1976 album Troubadour includes "Cocaine," a song that would be a major hit for Eric Clapton the following year. In the 2004 documentary To Tulsa and Back, Cale recalled, "I wrote 'Cocaine', and I'm a big fan of Mose Allison...So I had written the song in a Mose Allison bag, kind of cocktail jazz kind of swing...And Audie said, 'That's really a good song, John, but you oughta make that a little more rock and roll, a little more commercial.' I said, 'Great, man.' So I went back and recut it again as the thing you heard."[18] The song's meaning is ambiguous, although Eric Clapton describes it as an anti-drug song. He has called the song "quite cleverly anti-cocaine", noting:

It's no good to write a deliberate anti-drug song and hope that it will catch. Because the general thing is that people will be upset by that. It would disturb them to have someone else shoving something down their throat. So the best thing to do is offer something that seems ambiguous—that on study or on reflection actually can be seen to be "anti"—which the song "Cocaine" is actually an anti-cocaine song. If you study it or look at it with a little bit of thought ... from a distance ... or as it goes by ... it just sounds like a song about cocaine. But actually, it is quite cleverly anti-cocaine.[18]

By the time he recorded 5 in 1979, Cale had also met singer and guitarist Christine Lakeland, and the LP marks her first appearance on his albums. In the 2005 documentary To Tulsa and Back, Lakeland says they met backstage at a prison benefit show featuring B.B. King and Waylon Jennings. Cale and Lakeland would later marry. As William Ruhlmann observes in his AllMusic review of the album, "As Cale's influence on others expanded, he just continued to turn out the occasional album of bluesy, minor-key tunes. This one was even sparer than usual, with the artist handling bass as well as guitar on many tracks. Listened to today, it sounds so much like a Dire Straits album, it's scary." The release of 5 coincided with a notable live session with Leon Russell recorded at Russell's Paradise Studios in June 1979 in Los Angeles. The previously unseen footage features several tracks from 5, including "Sensitive Kind," "Lou-Easy-Ann," "Fate of a Fool," "Boilin' Pot," and "Don't Cry Sister." Lakeland also performs with Cale's band. While living in California in the late sixties, Cale worked in Russell's studio as an engineer. The footage was officially released in 2003 as J.J. Cale featuring Leon Russell: In Session at the Paradise Studios.

1980s

editCale moved to California in 1980 and became a recluse, living in a trailer without a telephone. In 2013, he reflected, "…I knew what fame entailed. I tried to back off from that. I had seen some of the people I was working with forced to be careful because people wouldn't leave them alone… What I'm saying, basically, is I was trying to get the fortune without having the fame."[19] Shades, which continued Cale's tradition of giving his albums one word titles, was recorded in various studios in Nashville and Los Angeles. It boasts an impressive list of top shelf session musicians, including Hal Blaine and Carol Kaye of the Wrecking Crew, James Burton, Jim Keltner, Reggie Young, Glen D. Hardin, Ken Buttrey, and Leon Russell, among many others. 1982's Grasshopper was recorded in studios in Nashville and North Hollywood, and while a more polished production, it continues Cale's exploration into a variety of musical styles that would become known as Americana.

His 1983 album #8 was poorly received, and he asked to be released from his contract with PolyGram. Lyrically speaking, with the exception of "Takin' Care of Business", the subject matter on #8 is unremittingly grim. The cynical "Money Talks" ("You'd be surprised the friends you can buy with small change…"), "Hard Times", "Unemployment" and "Livin' Here Too" deal with harsh economic woes and dissatisfaction with life in general, while the provocative "Reality" is about using drugs to escape many of the problems he chronicles on the album, singing "One toke of reefer, a little cocaine, one shot of morphine and things begin to change," and adding "When reality leaves, so do the blues." When later asked how he had spent the 1980s he replied: "Mowing the lawn and listening to Van Halen and rap."[20]

After making a name for himself in the seventies as a songwriter, Cale's own recording career came to a halt in the mid-1980s. Although he scored a handful of minor hits, Cale was indifferent to publicity, preferring to avoid the spotlight, so his albums never sold in high numbers.

1989's Travel-Log was the first solo album Cale produced himself without long-time producer Audie Ashworth, although Ashworth co-wrote the opening track "Shanghaid" with Cale. While the album has a travel theme, with titles like "Tijuana" and "New Orleans", Cale insisted he did not set out to make a concept album, and only recognized it after he picked the songs:

It's kind of ironic. When Andrew Lauder of Silvertone said he'd like to put out some tapes, I just got a bunch together and they put 'em out as an album. It wasn't till I got to listening to the album that I noticed that I'd written a bunch of tunes in the last four or five years about towns, and places, and travellin' around.[21]

In 1990 he explained in an interview, "In 1984 I was with a different record company, and it didn't seem to be working out too good, so I asked to get out of my contract, and that took a couple of years to shuffle the paper around. Then when I got through doin' that, I thought I'd take a little break from recording; maybe go in once or twice a year and record somethin' I'd written."[21]

1990s

editThe 1992 album Number 10 was Cale's second LP for Silvertone. Compared to his albums in the '70s and '80s, he employed fewer session players for this album, yet still achieved his signature sound. Notoriously wary of the spotlight, Cale quietly went about his own business his way, delivering his own unique blend of musical styles augmented by his laid-back vocal delivery. Ironically, in an era of grunge and the MTV Unplugged trends, Cale became immersed in electronics and synthesizers. "I did the unplugged, live kind of thing in the '70's and the '80's," he told one interviewer. "I've gone to the other direction now that all that's become popular. Been there done that! They didn't call it unplugged in those days but that is what it was…There is a fascination about electronics…It is an art form in itself."[22] 1994's Closer to You is best remembered for the change in sound from Cale's previous albums due to the prominence of synthesizers, with Cale employing the instrument on five of the twelve songs. Although the use of synthesizers may have seemed like a left turn for fans used to his laidback, rootsy sound, it was not new; Cale had used synthesizers on his 1976 Troubadour album. In an interview with Vintage Guitar in 2004, Cale acknowledged the dismay some fans felt, recalling:

…me playing with the synthesizer, everybody hated. [Then producer/manager] Audie Ashworth did the first eight albums, and those were kind of semi-popular, for an obscure songwriter like me. Then I started doing these albums in California with all synthesizers and me being the engineer. I liked those, but the folks wanted a little warmer kind of thing.[23]

Produced by Cale, Guitar Man differs from the albums he made in the seventies and early eighties in that while those records featured numerous top shelf session players, Cale provided the instrumentation on Guitar Man himself, augmented by wife Christine Lakeland on guitar and background vocals and drummer James Cruce on the opener "Death in the Wilderness." In his AllMusic review of the LP, Thom Owens writes, "Although he has recorded Guitar Man as a one-man band effort, it sounds remarkably relaxed and laid-back, like it was made with a seasoned bar band." In assessing the album, rock writer Brian Wise of Rhythm Magazine commented, "'Lowdown' is typical Cale shuffle, 'Days Go By' gives a jazzy feel to a song about smoking a certain substance while the traditional 'Old Blue' reprises a song that many might first have heard with The Byrds version during the Gram Parsons era."[22] After Guitar Man, Cale would take a second hiatus and not release another album for eight years.

Later career

editBetween 1996 and 2003, Cale released no new music but admiration for his work and musicianship only grew among his fans and admirers. In his 2003 biography Shakey, Neil Young remarked, "Of all the players I ever heard, it's gotta be [Jimi] Hendrix and J. J. Cale who are the best electric guitar players."[24] In the 2005 documentary To Tulsa and Back: On Tour with J.J. Cale, Cale's guitar style is characterized by Eric Clapton as "really, really minimal", adding "it's all about finesse". Mark Knopfler was also effusive in his praise for the Oklahoma troubadour, but Cale's early 90s experimental synth-heavy output left him at odds with the music industry. 2004's To Tulsa and Back reunited him with long-time producer Audie Ashworth, as he recalled to Dan Forte:

A few years ago, before Audie passed away, I said, "I've been making synthesizer records; ain't nobody likes 'em but me. I'll come to Nashville, and we'll hire all the guys who are still alive who played on the first albums." Audie said, "Great." I told him to book some studio time. But then he passed away, and I put the deal on hold. Eventually, I decided to do the same program, only go to Tulsa instead of Nashville. David Teegarden, of Teegarden & Van Winkle, is a drummer who has a studio, so I told him to get the guys in Tulsa that we used to play with when we were kids. I cut some there, and had some demos I did here at the house, and I sent them all to Bas [Hartong] and to Mike [Test].[25]

The album returns to the style and sound Cale became famous for – a mix of laid-back shuffles, jazzy chords, and bluesy rock and roll with layered vocals – but it also embraces technology, resulting in a cleaner sound than on Cale's earlier albums. Lyrically, Cale makes a rare foray into political songwriting with "The Problem," an indictment of then-President George W. Bush with lines like, "The man in charge, he don't know what he's doing, he don't know the world has changed." "Stone River" is an understated protest song about the water crisis in the West.

In 2004, Eric Clapton held the Crossroads Guitar Festival, a three-day festival in Dallas, Texas. Among the performers was J. J. Cale, giving Clapton the opportunity to ask Cale to produce an album for him. The two ended up recording the album together, releasing it as The Road to Escondido. A number of high-profile musicians also agreed to work on the album, including Billy Preston, Derek Trucks, Taj Mahal, Pino Palladino, John Mayer, Steve Jordan, and Doyle Bramhall II. In a coup, whether intended or not, the entire John Mayer Trio participated on this album in one capacity or another. Escondido is a city in San Diego County near Cale's home at the time located in the small, unincorporated town of Valley Center, California. Eric Clapton owned a mansion in Escondido in the 1980s and early '90s. The road referenced in the album's title is named Valley Center Road. The album won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Blues Album in 2008, with Cale writing 11 of the 14 tracks on the album, with two cuts, "Any Way the Wind Blows" and "Don't Cry Sister", being re-recordings of songs that Cale recorded previously in the 1970s. In a 2014 interview with NPR, Clapton spoke at length about Cale's influence on his music:

What seemed to evolve out of the '60s and into the '70s and then, in another way, the '80s — heavy metal came out of all of this stuff — was, like, volume and proficiency and virtuosity. There didn't seem to be any reasonable limit to that; it was just crazy. I wanted to go in the other direction and try to find a way to make it minimal, but still have a great deal of substance. That was the essence of J.J.'s music to me, apart from the fact that he summed up so many of the different essences of American music: rock and jazz and folk, blues. He just seemed to have an understanding of it all.[26]

Clapton, who toured with Delaney & Bonnie in 1969, recalled in the 2005 documentary To Tulsa and Back, "Delaney Bramlett is the one that was responsible to get me singing. He was the one who turned me on to the Tulsa community. Bramlett produced my first solo album and "After Midnight" was on it, and those [Tulsa] players played on it...461 Ocean Boulevard was my kind of homage to J.J."

Death

editCale died at the age of 74 in San Diego, California, on July 26, 2013, following a heart attack.[27][28][29][30] Stay Around, a posthumous album made of previously unreleased material, was released on April 26, 2019.

Tributes

edit- In 2014, Eric Clapton & Friends released the tribute album The Breeze: An Appreciation of JJ Cale. On it, Cale's tunes are covered by Clapton with Tom Petty, Mark Knopfler, John Mayer, Don White, Willie Nelson, Derek Trucks, Cale's wife Christine Lakeland, and others. In the video version of Call Me The Breeze for this album, Clapton declares of Cale, "He was a fantastic musician. And he was my hero."[31]

- Kevin Brown's 2015 album, Grit, contained a track called "The Ballad of J. J. Cale", in tribute to Brown's musical inspiration.[32]

- Hungarian alternative rock band Quimby's 2009 album, Lármagyűjtögető, contained a track called "Haverom a J. J. Cale" ("My Buddy J. J. Cale").[33][34]

Discography

edit- Naturally (1971)

- Really (1972)

- Okie (1974)

- Troubadour (1976)

- 5 (1979)

- Shades (1981)

- Grasshopper (1982)

- #8 (1983)

- Travel-Log (1989)

- Number 10 (1992)

- Closer to You (1994)

- Guitar Man (1996)

- To Tulsa and Back (2004)

- Roll On (2009)

- Stay Around (2019)

References

edit- ^ a b "Biography". JJ Cale official website. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "I was always a background person. It took me a while to adjust to the fact that people were looking at me 'cause I always just wanted to be part of the show. I didn't want to be the show." To Tulsa and Back: On Tour with J.J. Cale (2005)

- ^ Martin Chilton (July 25, 2014). "Eric Clapton: JJ Cale got me through my darkest days". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ To Tulsa and Back: On Tour with J.J. Cale, 2005

- ^ Ibid

- ^ Long-time collaborator drummer Jim Karstein remarked, 'You'll cut tracks with him and you'll listen to it and you'll think, "Well, I don't know about that one" and then he'll take the tapes away and he puts his secret sauce on 'em, you know, that nobody but he knows what it is that he does in the dark of night and then he'll come back out and you'll go "Wow!". Ibid

- ^ Lewis, Randy (January 10, 2009). "Musicians will honor Whisky founder Elmer Valentine". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Friedman, Barry. "Three Who Knew John". Daily Kos. Retrieved August 9, 2013., long-time friend and drummer Jimmy Karstein reflects on the early LA days

- ^ "The Great Rock Bible is under construction". Thegreatrockbible.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ Hoekstra, Dave (April 15, 1990). "Songwriter J. J. Cale prefers to remain in the background". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ "After Midnight by Eric Clapton Songfacts". Songfacts.com. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ Halsey, Derek (October 2004). "JJ Cale". Swampland.com. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ^ Cromelin, Richard (February 24, 2009). "J.J. Cale rolls on". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "J. J. Cale Biography". Sing 365.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ Hutchinson, Lydia (July 2013). "JJ Cale interview". Performingsongwriter.com. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ "Obituary: JJ Cale was music's towering figure". Gulfnews.com. July 28, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ "Remembering J.J. Cale". performingsongwriter.com. July 29, 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b The Best of Everything Show, with Dan Neer

- ^ Hutchinson, Lydia (July 2013). "JJ Cale interview". Performingsongwriter.com. Retrieved June 24, 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "JJ Cale". The Telegraph. July 28, 2013. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Newton, Steve (March 27, 2016). "LAID-BACK LEGEND J.J. CALE TELLS ME "THERE'S NO HURRY"". Ear Of Newt. Retrieved June 25, 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Wise, Brian (July 28, 2013). "Tribute – J.J. Cale in 1996". Addicted to Noise. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ McDonough, Jimmy (2013). Shakey: Neil Young's Biography. Random House. ISBN 9781446414545.

- ^ Forte, Dan (2004). "J.J. Cale: Clapton Mentor". Ear Of Newt. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- ^ Westervelt, Eric (July 26, 2014). "Eric Clapton and J J Cale : Notes on a Friendship". NPR. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ Gripper, Ann (July 27, 2013). "JJ Cale dead at 74: Tributes paid to singer songwriter after his death from a heart attack". Daily Mirror. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "JJ Cale passed away at 8:00 pm on Friday July 26 at Scripps Hospital in La Jolla, CA". JJ Cale official website. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Castillo, Mariano (July 27, 2013). "Writer of hits JJ Cale dead at 74". CNN. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Cale's agent confirms his death". The Rosebud Agency.

- ^ ""Call Me The Breeze" - Eric Clapton Videos". Ericclapton.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- ^ "Kevin Brown Trio - Kevin Brown Trio, Black Mountain Jazz, Kings Arms, Abergavenny, 25/10/2015. | Review". The Jazz Mann. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ "Quimby, Lemezek". Quimby. April 25, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Songbook, Haverom a J. J. Cale" (in Hungarian). Songbook. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

External links

edit- Official website

- J. J. Cale discography at Discogs

- J. J. Cale at IMDb

- The Long Reach of J.J. Cale on MTV.com

- J. J. Cale discography at MusicBrainz