The Ulma family (Polish: Rodzina Ulmów) or Józef and Wiktoria Ulma with Seven Children (Polish: Józef i Wiktoria Ulmowie z siedmiorgiem Dzieci) were a Polish Catholic family in Markowa, Poland, during the Nazi German occupation in World War II who attempted to rescue Polish Jewish families by hiding them in their own home during the Holocaust. They and their children were summarily executed on 24 March 1944 for doing so.[1][2]

Ulma family | |

|---|---|

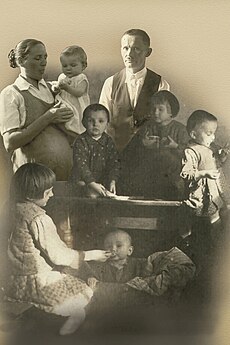

Photograph of the Ulma family, circa 1943. | |

| Martyrs | |

| Born | 2 March 1900 (Józef) 10 December 1912 (Wiktoria) 18 July 1936 (Stanisława) 6 October 1937 (Barbara) 5 December 1938 (Władysław) 3 April 1940 (Franciszek) 6 June 1941 (Antoni) 16 September 1942 (Maria) 24 March 1944 (unborn child) Markowa, Congress Poland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 24 March 1944 Markowa, Occupied Poland, Nazi Germany |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 10 September 2023, Ludowy Klub Sportowy Markovia, Markowa, Poland by Cardinal Marcello Semeraro (on behalf of Pope Francis) |

| Major shrine | Church of Saint Dorothy, Markowa, Poland |

| Feast | 7 July |

Notably, despite the murder of the Ulmas—meant to strike fear into the hearts of villagers—their neighbours continued to hide Jewish fugitives until the end of World War II in Europe. At least 21 Polish Jews survived in Markowa during the occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany.[3] In 1995 the adult Ulmas have been recognized by the State of Israel as Righteous Among the Nations. They are venerated in the Catholic Church as martyrs following their beatification by Pope Francis in 2023; their feast day is celebrated on 7 July (day of the anniversary of Józef and Wiktoria's wedding).[4]

Biography

editJózef Ulma

editJózef Ulma (2 March 1900 – 24 March 1944) from the Village of Markowa near in Przemyśl, son of Marcin Ulma and Franciszka Ulma (née Kluz), well-off farmers. In 1911, he took short courses in a general school. In his youth, he became involved in social activities. At the age of seventeen, he was a member of the association in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Przemyśl, whose purpose, apart from prayer, was to collect funds for the construction and maintenance of churches and chapels.[5] In addition, he became an active member of the Catholic Youth Association and later the Rural Youth Association. At this time he worked as a librarian and photographer. He was also known locally for his passions in gardening, beekeeping, and bookbinding.[6]

In 1921 to 1922, he completed his compulsory military service in Grodno.[5] From 1 November 1929 to 31 March 1930, he studied at the National Agricultural School in Plzeň. After obtaining a diploma, he became a market gardener, growing fruit trees, raising bees and silkworms. In 1933, he received an award from the Przeworsk District Agricultural Society for these activities. He was the first to introduce electricity to Markowa. Furthermore, he was passionate about photography, and indulged in it during cultural events in his village and during family celebrations. He also wrote articles for a local weekly newspaper. In addition, he was a member of the Agricultural Circle and other organizations.

Wiktoria Ulma

editWiktoria Ulma, née Niemczak, (10 December 1912 – 24 March 1944) from the Village of Markowa near in Łańcut, daughter of Jan Niemczak and Franciscka Niemczak (née Homa). Her mother died when she was six years old.[7] She completed her primary and secondary education in her hometown, after which she took courses at the People's University in Gać.[8] In her hometown, she was a member of an amateur theater troupe. Wiktoria was an educated housewife, taking care of the home and the children.[9] Through hard work, persistence and determination, the Ulmas were able to purchase a bigger farm (5 hectares (12 acres) in size) in Wojsławice near Sokal (now Ukraine), and had already begun planning a relocation when the war began.[8]

Józef and Wiktoria married on 7 July 1935. After their marriage, they earned their living as farmers on a small farm they owned. Together they had six children and were expecting their seventh:

- Stanisława (born 18 July 1936), aged 8

- Barbara (born 6 October 1937), aged 7

- Władysław (born 5 December 1938), aged 6

- Franciszek (born 3 April 1940), aged 4

- Antoni (born 6 June 1941), aged 3

- Maria (born 16 September 1942), aged 2

- Unborn child, aged 8 months

The couple were active members in the Church of Saint Dorothy in Markowa. They deepened their faith through family prayer and participation in the sacramental life of the church.[10] They both belonged to the Association of the Living Rosary.[11] After the outbreak of World War II, Józef was mobilized and took part in the Polish campaign.[12]

Holocaust rescue

editExtermination of Jews in Markowa

editBefore World War II, nearly 30 Jewish families (about 120 people) lived in Markowa, near Łańcut.[13] After the beginning of the German occupation, the village was incorporated into the Jarosław County within the General Government.[14]

In late July[15] or early August 1942,[16] Jarosław County became part of Operation Reinhard. The local Jews were gathered in a transit camp in Pełkinie, from where they were transported either to the Belzec extermination camp or executed in the forests near Wólka Pełkińska. In some villages and settlements, residents were murdered on the spot.[15][17]

Only a few Jews from Markowa, probably no more than 6 or 8 people, heeded the German authorities' call and reported for the supposed "resettlement". The rest, numbering around several dozen, went into hiding.[18] Some found shelter with Polish families, while others hid in farm buildings without the knowledge of the owners or roamed the nearby forests and fields. The fugitives were hunted by German gendarmes and Polish Blue Police officers, who killed any Jews they captured.[18]

The largest manhunt for Jews hiding in Markowa occurred on 13 December 1942. It was ordered by the village head, Andrzej Kud, at the behest of the German authorities. Members of the local fire brigade and village watch, possibly supported by Blue Police officers and ordinary villagers, participated in the manhunt. Between a dozen and 25 Jewish men, women, and children were captured. They spent the night of 13/14 December in the local jail. The next day, German gendarmes arrived from Łańcut and executed all the Jews at an old trench, which was also used as an animal burial site.[19] According to Jakub Einhorn, a Jew from Markowa who survived the German occupation, the Poles involved in the manhunt were notably zealous and even brutal. The Jews detained in the jail were reportedly tortured and robbed; a young Jewish woman was said to have been repeatedly raped.[20] However, the credibility of Einhorn's account is disputed.[a][21]

Aid given to Jews by the Ulma family

editIn the summer and autumn of 1942, the Nazi police deported several Jewish families of Markowa as part of Operation Reinhard, the Nazi plan to exterminate Polish Jews in the General Government district of German-occupied Poland.[8] Only those who were hidden in Polish peasants' homes survived. Eight Jews found shelter with the Ulmas: six members of the Szall (Szali) family from Łańcut including father, mother and four sons, as well as the two daughters of Chaim Goldman, Golda (Gienia) and Layka (Lea) Didner.[b][22] Józef Ulma put all eight Jews in the attic. They learned to help him with supplementary jobs while in hiding, to ease the incurred expenses.[8]

The two Jewish families hidden by the Ulmas stayed at their farm until the spring of 1944. No extraordinary precautions were taken to hide them. The Jews lived in the attic of the house, and retreated to the attic only at night or in times of danger.[23][24] The Ulmas were supported in their efforts by Józef's close friend, Antoni Szpytma.[25]

Arrest and execution

editThe Ulma family were denounced by Włodzimierz Leś, a member of the Blue Police, who had taken possession of the Szall (Szali) family's real estate in Łańcut in spring 1944 and wanted to get rid of its rightful owners.[8] As a Greek Catholic[26] from the village of Biała near Rzeszów, which was considered "Ruthenian",[27] he is often referred to as Ukrainian in various sources.[c][26] Before the war, Leś had connections with the Goldman family. In the early period of the occupation, he agreed to shelter them in exchange for part of their property. However, when the Germans intensified their repression against those hiding Jews, Leś refused further help and seized the property left under his care. The Goldman family then took refuge with the Ulmas, but they continued to demand the return of their property from Leś. Probably wanting to rid himself of the rightful owners of the seized property, Leś betrayed the Goldman family and the Ulma family hiding them to the German gendarmerie. He had previously visited the Ulmas under the pretense of asking for a photograph, ensuring during that visit that the Goldman family was hiding in their home.[28]

Course of the massacre

editIn the early morning hours of 24 March 1944 a patrol of German police from Łańcut under Lieutenant Eilert Dieken came to the Ulmas' house which was on the outskirts of the village. The four coachmen with horses and carts were instructed to report to the town stables and await further instructions. According to the German orders, each coachman was to come from a different village, with none from Markowa.[29] On March 24, around 1:00 AM, the coachmen were ordered to drive to the gendarmerie post and transport a group of German gendarmes and Polish Blue Policemen to Markowa. The expedition was personally led by Lieutenant Eilert Dieken, the commander of the Łańcut gendarmerie. He was accompanied by four other Germans:[30] Josef Kokott (a Volksdeutsche from Czechoslovakia), Michael Dziewulski, Gustaw Unbehend, and Erich Wilde (a Volksdeutsche from the Lublin Land).[31] Additionally, from 4 to 6 members of the Polish Blue Police participated in the operation. The names of two policemen were identified: Eustachy Kolman and Włodzimierz Leś.[30]

Just before dawn, the wagons arrived in Markowa. The Germans ordered the coachmen to stay aside while they, along with the Blue Policemen, proceeded to the Ulma farm. Leaving the policemen as guards, the Germans surrounded the house and caught all eight Jews belonging to the Szali and Goldman families. They shot them in the back of the head according to eyewitness Edward Nawojski and others, who were ordered to watch the executions. Then the German gendarmes killed the pregnant Wiktoria and her husband so that the villagers would see what punishment awaited them for hiding Jews. The six children began to scream at the sight of their parents' bodies. After consulting with his superior, twenty-three year old Jan Kokott, a Czech Volksdeutscher from Sudetenland serving with the German police, shot three or four of the Polish children while the other Polish children were murdered by the remaining gendarmes.[22] The last of the Jews to be killed was the 70-year-old father of the Goldman brothers.[29] Within several minutes 17 people were killed. It is likely that during the mass execution Wiktoria went into labour because the witness to her exhumation testified that he saw a head of a newborn baby between her legs.[9]

The names of the other Nazi executioners are also known from their frequent presence in the village (Eilert Dieken, Michael Dziewulski and Erich Wilde). After the massacre, the Germans began looting the Ulma farm and the belongings of the murdered Jews. Kokott seized a box of valuables found on Gołda Grünfeld's body. The plundering was so extensive that Dieken had to summon two additional wagons from Markowa to transport all the stolen goods.[32] The village Vogt (Polish: Wójt) Teofil Kielar was ordered to bury the victims with the help of other witnesses. He asked the German commander, whom he had known from prior inspections and food acquisitions, why the children too had been killed. Dieken answered in German, "So that you would not have any problems with them."[22] Another gendarme, Gustaw Unbehend, asked about the reason for the murder of children, to which Dieken replied, "I am the commander, and I know what I'm doing".[33]

At the request of the Poles who had been brought to bury the dead, the gendarmes agreed to bury the Ulmas and the Jews in separate graves.[32] The massacre concluded with a drinking session held at the scene (for which the village leader had to supply the Germans with three liters of vodka). After it ended, the gendarmes and Blue Policemen returned to Łańcut with six wagons full of looted goods.[29]

On 11 January 1945, in defiance of the Nazi prohibition, relatives of the Ulmas exhumed the bodies, which were originally buried in front of the house, and found Wiktoria's seventh child, emerged from her womb, in the parents' grave pit. A funeral was later held in the Church of Saint Dorothy in Markowa and the family's remains were then buried in Markowa cemetery.[34]

Aftermath

editA report from the local commander of the People's Security Guard noted that the massacre of the Ulma family "made a very unpleasant impression on the Polish population".[35] Yehuda Erlich, who had been hiding in the vicinity of Markowa during the occupation, wrote an account in which he mentioned that the crime had so profoundly shocked the local population that 24 Jews were later found dead in the area around Markowa, killed by their Polish caretakers out of fear of denunciation. His account is cited, among other places, in the information about the Ulma family on the Yad Vashem Institute's website.[36]

In 2011, Mateusz Szpytma, a historian at the Institute of National Remembrance and a researcher of the Ulma family's history, speculated in the magazine Więź that the massacre Erlich mentioned may have occurred in the neighboring village of Sietesz, likely two years before the Ulmas' deaths.[37] In an article published three years later, he pointed out that no other account or archival document confirms that bodies of murdered Jews were found in the fields near Markowa. He also suggested that Erlich's memory might have conflated the execution of the Ulma family with the roundups of Jews hiding in Markowa and Sietesz, which took place in 1942 with the involvement of local Poles.[d][38] However, Jan Grabowski and Dariusz Libionka are convinced of the accuracy of Erlich's account.[39]

At least 21 Jews survived the war in Markowa, hiding with Polish families,[40] although not all of the survivors were residents of the village.[41]

Commemoration

editOn 13 September 1995, Józef and Wiktoria Ulma were posthumously bestowed the titles of Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem.[24][42] Their medals of honor were presented to Józef's surviving brother, Władysław Ulma. Their certificate states that they tried to save Jews at the risk of their lives, but fails to mention that they died for them, as noted in the book Godni synowie naszej Ojczyzny.[43]

On 24 March 2004, the 60th anniversary of their execution, a stone memorial was erected in the village of Markowa to honor the memory of the Ulma family.[9][44] The inscription on the memorial reads:

Saving the lives of others they laid down their own lives. Hiding eight elder brothers in faith, they were killed with them. May their sacrifice be a call for respect and love to every human being! They were the sons and daughters of this land; they will remain in our hearts.[22]

At the unveiling of the monument, the Archbishop of Przemyśl, Archbishop Józef Michalik – the President of the Polish Bishops' Conference – celebrated a solemn Mass.[22]

The local diocesan level of the Roman Catholic Church in Poland initiated the Ulmas' beatification process in 2003.[45] The Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone spoke in Rome of the heroic Polish family on 24 January 2007 during the inauguration of the Italian edition of Martin Gilbert's book I giusti. Gli eroi sconosciuti dell'Olocausto ("The Righteous. Unknown Heroes of the Holocaust").[22]

Special commemorations were held in Markowa on 24 March 2007 – 63 years after the Ulma, Szall and Goldman families were massacred. Mass was celebrated, followed by the Way of the Cross with the intention of the Ulma family's beatification. Among the guests was the President of the Council of Kraków, who laid flowers at the monument to the dead. The students of the local high school presented their own interpretation of the Ulmas' family decision to hide Jews in a short performance entitled Eight Beatitudes. There was also an evening of poetry dedicated to the memory of the murdered. Older neighbors and relatives who knew them spoke about the life of the Ulmas. One historian from the Institute of National Remembrance presented archival documents; and, the Catholic diocesan postulator explained the requirements of the beatification process.[22] On 24 May 2011, the completed documentation of their martyrdom was passed on to Rome for completion of the beatification process.[46]

The fate of the Ulmas became a symbol of martyrdom of Poles killed by the Germans for helping Jews. A new Polish "National day of the Ulma family" has first been suggested by the former Prime Minister Jarosław Kaczyński. Subsequently, the growing support for a more formal commemoration inspired the Sejmik of Podkarpackie Voivodeship to name 2014 the Year of the Ulma family (Rok Rodziny Ulmów).[47] The new Markowa Ulma-Family Museum of Poles Who Saved Jews in World War II was scheduled to be completed in 2015.[48] On 17 March 2016, The Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II was opened in Markowa in presence of the President of Poland, Andrzej Duda.[49]

Cause of beatification

editOn 17 September 2003, the Diocese of Pelplin, Bishop Jan Bernard Szlaga initiated the beatification process of 122 Polish martyrs who died during World War II, including Józef and Wiktoria Ulma with their seven children among the others. On 20 February 2017, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints was allowed to take over management of the process of Ulma family by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Przemyśl.[50]

On 18 December 2022, Pope Francis declared the entire family to be martyrs and determined that they would be beatified on 10 September 2023, a celebration that was held in their native Markowa and presided over by Cardinal Marcello Semeraro on the Pope's behalf.[51][52] Between 30 March and 1 April 2023, the remains of the Ulma family were exhumed in preparation for their beatification, after which they would be placed in a sarcophagus, prepared in advance, in the side altar dedicated in the Church of Saint Dorothy in Markowa.[53]

The beatification of the Ulma family is unique within the Catholic Church, as they are the first family to be beatified together in the history of the church in the 21st century. After some news reports suggested that the beatification would represent the first beatification of an unborn or pre-born child, the Dicastery for the Causes of Saints released an official clarification on 5 September 2023, stating that "this [unnamed] son was delivered at the time of his mother's martyrdom" (based on the evidence that his remains were found emerged from his mother's womb in the original grave), and he was therefore included with the other martyred Ulma children, under the Catholic doctrine of baptism of blood.[54]

Accountability of the perpetrators

editShortly after the Germans murdered the Ulma family and the Jews they were sheltering, the local unit of the People's Security Guard initiated actions to identify the informant.[35] Their investigation suggested that Włodzimierz Leś betrayed the Ulma family.[23] The officer did not survive the war; on 10 September 1944, a few weeks after the Red Army entered Łańcut, he was shot by the Polish underground.[55][56] It is possible that he was executed by the verdict of the Civil Special Court in Przemyśl,[56] although neither the sentence nor its justification has survived.[23]

Only one of the German participants in the murder of the Ulma family and the Jews they sheltered was brought to justice: the gendarme Josef Kokott. He was arrested in Czechoslovakia in 1957 and extradited to Poland. On 30 August 1958, the provincial court in Rzeszów sentenced him to death. However, the State Council of the Polish People's Republic commuted his sentence to life imprisonment and later to 25 years in prison.[57] Kokott died in 1980 in a prison in Racibórz[57] (according to other sources, in Bytom).[31]

The leader of the punitive expedition, Lieutenant Eilert Dieken, worked as a policeman in Esens, West Germany, after the war. The Dortmund prosecutor's office investigated his activities in occupied Poland as part of an inquiry into crimes committed in Jarosław County. However, the investigation was closed in 1971 after it was determined that Dieken had died many years earlier of natural causes (in 1960).[14]

Erich Wilde died in August 1944. Michael Dziewulski evaded criminal responsibility after the war.[31]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ After the war, criminal proceedings were initiated against several residents of Markowa on suspicion of involvement in crimes against the Jewish population. The accusations were mostly based on the testimony of Jakub Einhorn. However, none of the suspects were ultimately convicted. This was partly due to the courts deeming Einhorn's testimony insufficiently credible. During the proceedings, it was demonstrated that some of the events he claimed to have witnessed firsthand were, in fact, known to him only through third-party accounts (Szpytma (2014, p. 27)).

- ^ Chaim Goldman was most likely the brother of Saul Goldman from Łańcut (Grądzka-Rejak & Namysło (2019, pp. 324–325)).

- ^ Grabowski & Libionka (2016, p. 1834) are highly critical of attributing Ukrainian origins to Leś. In their view, this assumption, repeated in all texts about the Ulma family, serves to diffuse responsibility for the betrayal.

- ^ At the same time, Erlich was not an eyewitness to any of these events (Szpytma (2014, p. 14)).

References

edit- ^ Mateusz Szpytma, "The Righteous and their world. Markowa through the lens of Józef Ulma" Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, Institute of National Remembrance, Poland.

- ^ (in Polish) Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Wystawa „Sprawiedliwi wśród Narodów Świata”– 15 czerwca 2004 r., Rzeszów. Archived 2009-06-11 at the Wayback Machine "Polacy pomagali Żydom podczas wojny, choć groziła za to kara śmierci – o tym wie większość z nas." (Exhibition "Righteous among the Nations." Rzeszów, 15 June 2004. Subtitled: "The Poles were helping Jews during the war - most of us already know that."); accessed 8 November 2008.

- ^ Polish Press Agency PAP. "Commemorations in Markowa, on the 71st anniversary of the murder of Ulma family" [W Markowej uczczono 71. rocznicę zamordowania Ulmów i ukrywanych przez nich Żydów]. Dzieje.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2016-08-27. Retrieved 2018-02-22 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Guzik, Paulina (2023-09-10). "As entire Ulma family beatified in Poland, pope hails them as 'ray of light in the darkness'". www.oursundayvisitor.com. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ a b "Samarytanie z Markowej. Słudzy Boży Ulmowie – rodzina, która oddała swoje życie za pomoc Żydom – Narodowy Instytut Kultury i Dziedzictwa Wsi" [The Samaritans of Markowa: The Blessed Ulma Family – A Family Who Gave Their Lives to Help Jews – National Institute of Rural Culture and Heritage]. Narodowy Instytut Kultury I Dziedzictwa Wsi (in Polish). 2023-09-06. Archived from the original on 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Szpytma & Szarek (2018, pp. 9–17)

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Poland (25 February 2018). "The Ulma Family: Symbol of Polish Heroism in the Face of Nazi German Brutalities". German Camps, Polish Heroes. Instytut Lukasiewicza. What Was the Truth? Project under the honorary patronage of the President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda. Project coordinators: Auschwitz Memorial and State Museum in Oświęcim, and Institute of National Remembrance, Warsaw. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Teresa Tyszkiewicz. "Rodzina Ulmów. Miłość silniejsza niż strach". Adonai.pl (in Polish). Bibliography: M. Szpytma: "Żydzi i ofiara rodziny Ulmów z Markowej podczas okupacji niemieckiej" [in:] W gminie Markowa, Vol. 2, Markowa 2004, p. 35; M. Szpytma, J. Szarek: Sprawiedliwi wśród narodów świata, Kraków 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-02-24 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Mateusz Szpytma (2006-03-25). "Lay down their lives for their fellow man. Heroic family who perished for hiding Jews" [Oddali życie za bliźnich. Bohaterska rodzina Ulmów zginęła za ukrywanie Żydów]. Nasz Dziennik. 72 (2482). Archived from the original on 2014-03-08 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Small Polish town gears up for beatification of entire family killed for saving Jews". Crux. 2023-09-06. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Soler, Ignacy (2022-12-20). "The Ulma family of Markowa: martyrs of the Christian faith". Omnes. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ "The Ulma family: Polish martyrs who saved Jews". TheArticle. 2023-09-08. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ^ Szpytma & Szarek (2018, p. 27)

- ^ a b Szpytma (2014, p. 6)

- ^ a b Grabowski & Libionka (2016, p. 1829)

- ^ Szpytma (2014, p. 7)

- ^ Szpytma & Szarek (2018, p. 29)

- ^ a b Szpytma (2014, pp. 7–8)

- ^ Szpytma (2014, pp. 8–10)

- ^ Grabowski & Libionka (2016, pp. 1864–1868)

- ^ Szpytma, Mateusz. "Czyje te bezdroża? – odpowiedź wiceprezesa IPN na tekst "Gazety Wyborczej"" [Whose Backroads Are These? – A Response from the Deputy President of the Institute of National Remembrance to the "Gazeta Wyborcza" Article]. ipn.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wlodzimierz Redzioch, interview with Mateusz Szpytma, historian from the Institute of National Remembrance (4 March 2016), "They gave up their lives." Tygodnik Niedziela weekly, 16/2007, Editor-in-chief: Fr Ireneusz Skubis Częstochowa, Poland. Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Grądzka-Rejak & Namysło (2019, pp. 324–325)

- ^ a b Gutman, Israel, ed. (2009). Księga Sprawiedliwych wśród Narodów Świata. Ratujący Żydów podczas Holocaustu: Polska [Whose Backroads Are These? – A Response from the Deputy President of the Institute of National Remembrance to the "Gazeta Wyborcza" Article] (in Polish). Vol. II. Kraków: Fundacja Instytut Studiów Strategicznych. p. 777. ISBN 978-83-87832-59-9.

- ^ Szpytma (2014, p. 12)

- ^ a b Grabowski & Libionka (2016, p. 1834)

- ^ Szpytma & Szarek (2018, p. 48)

- ^ Szpytma & Szarek (2018, pp. 48–50)

- ^ a b c "Rocznica masakry rodziny Ulmów" [The Anniversary of the Ulma Family Massacre]. polskieradio.pl (in Polish). 24 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-05-27.

- ^ a b Szpytma & Szarek (2018, p. 50)

- ^ a b c Friedrich, Klaus-Peter (2011). "Jürgen Stroop, Żydowska dzielnica mieszkaniowa w Warszawie już nie istnieje! (Besprechungen und Anzeigen)" [Jürgen Stroop: The Jewish Residential District in Warsaw No Longer Exists! (Reviews and Notices)]. Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung (in Polish and German). 60 (1): 134.

- ^ a b Szpytma & Szarek (2018, p. 56)

- ^ Domagała-Pereira, Katarzyna; Bercal, Joanna (10 September 2023). "Zginęli, bo ratowali Żydów. Brutalne morderstwo Ulmów" [They Died Because They Saved Jews: The Brutal Murder of the Ulma Family]. dw.com (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ "Saving Jews: Polish Righteous". 2008-01-20. Archived from the original on 2008-01-20. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Żbikowski (2006, p. 919)

- ^ "Jozef and Wiktoria Ulma". www.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ Szpytma, Mateusz (October 2011). "Sprawiedliwi i inni" [The Righteous and Others]. Więź (in Polish). 10 (636): 100–101.

- ^ Szpytma (2014, p. 14)

- ^ Grabowski & Libionka (2016, pp. 1883–1885)

- ^ Szpytma & Szarek (2018, p. 59)

- ^ Grabowski & Libionka (2016, p. 1838)

- ^ "Jozef and Wiktoria Ulma | Paying the Ultimate Price | Themes | A Tribute to the Righteous Among the Nations". www.YadVashem.org. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ^ Jolanta Chodorska, Alicja Augustyniak, Godni synowie naszej Ojczyzny, Wyd. Sióstr Loretanek (publishing), 2002, Warsaw, Poland; ISBN 83-7257-102-3.

- ^ Joe Riesenbach, "The Story of Survival". Footnote by Richard Tyndorf

- ^ Anna Domin (2015), Słudzy Boży - Józef i Wiktoria Ulmowie z Dziećmi. Nasi patronowie. Stowarzyszenie Szczęśliwy Dom. Internet Archive.

- ^ Fight Hatred (27 May 2011), "Sainthood for Martyred Polish Jew-Defenders", Jabotinsky International Center; accessed 30 August 2016.

- ^ Potocka, Katarzyna. "Rok Rodziny Ulmów", Wrota Podkarpackie, 2014

- ^ Polskie Radio (24 March 2014), Ulmowie poświęcili życie by ratować Żydów. 70. rocznica niemieckiej zbrodni (On the 70th Anniversary of the Ulma Martyrdom); PolskieRadio.pl; accessed 30 August 2016.

- ^ "Uroczystość otwarcia Muzeum Polaków Ratujących Żydów im. Rodziny Ulmów w Markowej" [The Opening Ceremony of the Museum of Poles Saving Jews Named After the Ulma Family in Markowa]. Dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ^ "Proces beatyfikacyjny Rodziny Ulmów będzie prowadzony przez Archidiecezję Przemyską | Archidiecezja Przemyska". Archidiecezja Przemyska (in Polish). 2017-03-08. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ^ "Church to beatify Polish family killed for helping Jews in WW2 - Vatican News". www.vaticannews.va. 2022-12-17. Retrieved 2022-12-18.

- ^ CNA. "A married couple with seven children to be beatified by the Catholic Church for martyrdom by Nazis". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ^ "Bodies of Ulma Family Exhumed: Beatification for Poles Who Helped Jews Escape Nazis Set for Sept. 2023". ChurchPOP. 2023-04-17. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ Coppen, Luke (2023-09-05). "Here's what's special about the Ulma family beatification". The Pillar. Retrieved 2023-09-10.

- ^ Szpytma, Mateusz (2023). Sprawiedliwi i ich świat: w fotografii Józefa Ulmy [The Righteous and Their World: In the Photography of Józef Ulma] (in Polish). Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance. p. 40. ISBN 978-83-8229-842-0.

- ^ a b Grabowski & Libionka (2016, p. 1831)

- ^ a b Pawłowski, Jakub (September 2019). "Proces Józefa Kokota – mordercy rodziny Ulmów" [The Trial of Józef Kokot – The Murderer of the Ulma Family]. Podkarpacka Historia (in Polish). 9–10 (57–58). ISSN 2391-8470.

Bibliography

edit- The Righteous and their world. Markowa through the lens of Józef Ulma, by Mateusz Szpytma Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, Institute of National Remembrance, Poland

- Gisele Hildebrandt, Otto Adamski. "Markowa" Dorfimfersuchungen in dem alten deutsch-ukrainischen Grenzbereich von Landshuf. 1943. Kraków.

- (in Polish) Interview with the President of the Committee for the Monument in Markowa

- Józef and Wiktoria Ulma at the Israeli Holocaust memorial – Yad Vashem

- Martyred and Blessed Together: The Extraordinary Story of the Ulma Family

- Grabowski, Jan; Libionka, Dariusz (2016). "Bezdroża polityki historycznej. Wokół Markowej, czyli o czym nie mówi Muzeum Polaków Ratujących Żydów podczas II Wojny Światowej im. Rodziny Ulmów" [The Backroads of Historical Policy: Around Markowa, or What the Museum of Poles Saving Jews During the Second World War Named After the Ulma Family Does Not Mention]. Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały (in Polish). 12. Warsaw: Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów IFiS PAN. ISSN 1895-247X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Grądzka-Rejak, Martyna; Namysło, Aleksandra (2019). Represje za pomoc Żydom na okupowanych ziemiach polskich w czasie II wojny światowej [Repressions for Helping Jews in the Occupied Polish Territories During the Second World War] (in Polish). Vol. I. Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. ISBN 978-83-8098-667-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Szpytma, Mateusz; Szarek, Jarosław (2018). Rodzina Ulmów [Ulma Family] (in Polish). Kraków: RAFAEL. ISBN 978-83-7569-863-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Szpytma, Mateusz (2014). "Zbrodnie na ludności żydowskiej w Markowej w 1942 roku w kontekście postępowań karnych z lat 1949–1954" [Crimes Against the Jewish Population in Markowa in 1942 in the Context of Criminal Proceedings from 1949–1954]. Zeszyty Historyczne WiN-u (in Polish). 40. ISSN 1230-106X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Żbikowski, Andrzej, ed. (2006). Polacy i Żydzi pod okupacją niemiecką 1939–1945. Studia i materiały [Poles and Jews Under German Occupation 1939–1945: Studies and Materials] (in Polish). Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. ISBN 83-60464-01-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)