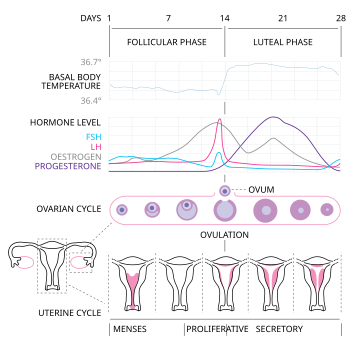

The menstrual cycle is on average 28 days in length. It begins with menses (day 1–7) during the follicular phase (day 1–14), followed by ovulation (day 14) and ending with the luteal phase (day 14–28).[1] Unlike the follicular phase which can vary in length among individuals, the luteal phase is typically fixed at approximately 14 days (i.e. days 14–28)[1] and is characterized by changes to hormone levels, such as an increase in progesterone and estrogen levels, decrease in gonadotropins such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), changes to the endometrial lining to promote implantation of the fertilized egg, and development of the corpus luteum. In the absence of fertilization by sperm, the corpus luteum degenerates leading to a decrease in progesterone and estrogen, an increase in FSH and LH, and shedding of the endometrial lining (menses) to begin the menstrual cycle again.[1]

Hormonal events

editAfter ovulation and release of the oocyte, the anterior pituitary hormones–follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) are released and cause the remaining parts of the dominant follicle to transform into the corpus luteum. It continues to grow during the luteal phase after ovulation and produces significant amounts of hormones, particularly progesterone, and, to a lesser extent, estrogen and inhibin. Progesterone plays a vital role in making the endometrium receptive to implantation of the embryo and supportive of early pregnancy. High levels of progesterone inhibit the follicular growth. The increase in estrogen and progesterone also lead to increased basal body temperature during the luteal phase.[2]

The LH surge that occurs during ovulation triggers the release of the oocyte and its cumulus oophorus from the ovary and into the fallopian tube and triggers the oocyte to divide and enter metaphase of meiosis II (46 or 2n chromosome) and extrude its first polar body. The oocyte will only continue through meiosis and extrude its second polar body once it is fertilized. Ovulation occurs ~35 hours after the beginning of the LH surge or ~10 hours following the LH surge. Several days after ovulation, the increasing amount of estrogen produced by the corpus luteum may cause one or two days of fertile cervical mucus, lower basal body temperatures, or both. This is known as a "secondary estrogen surge".[3]

The hormones released by the corpus luteum suppress production of the FSH and LH from the anterior pituitary gland. The corpus luteum relies on LH activation on its receptors in order to survive. The loss of the corpus luteum can be prevented by implantation of an embryo: after implantation, human embryos produce human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG),[4] which is structurally similar to LH and can preserve the corpus luteum. If implantation occurs, the corpus luteum will continue to produce progesterone for eight to twelve weeks, after which the placenta takes over this function.[5] In the absence of fertilization, hCG is not produced and the corpus luteum will atrophy in 10–12 days (Luteolysis or luteal regression). The death of the corpus luteum results in falling levels of progesterone and estrogen. The drop in ovarian hormones releases negative feedback on LH and FSH, thereby increasing LH and FSH concentrations and leading to shedding of the endometrium and another round of ovarian follicle selection.[6]

Uterine events

editDuring the follicular phase in the menstrual cycle, the uterine endometrium is in the proliferative phase which is characterized by an increase in circulating estrogen produced by the developing follicle. Increased estradiol alters the endometrial lining and promotes proliferation of epithelial cells, thickening of the tissue, and elongation of the spiral arteries that provide nutrients to the growing tissue. Estrogen also makes the endometrium more sensitive to progesterone in preparation for the luteal phase.[citation needed]

After ovulation and during the luteal phase, the uterine endometrium is in the secretory phase which is characterized by the production of progesterone from the growing corpus luteum. Progesterone inhibits endometrial proliferation, and preserves uterine tissue in preparation for fertilized egg implantation. At the end of the luteal phase, progesterone levels fall and the corpus luteum atrophies. The drop in progesterone leads to endometrial ischemia which will subsequently shed in the beginning of the next cycle at the start of menses.[1] This last stage in the luteal or secretory phase may be called the ischemic phase and lasts just for one or two days.[7]

Symptoms

editChanges in the level of progesterone during this phase may cause typical symptoms of pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS), such as:

- Anxiety

- Headaches

- Mood swings

- Irritability

- Tender breasts

- Weight gain

- Trouble sleeping

- Changes in sexual desire

- Bloating

- Emotional stresses

References

edit- ^ a b c d Reed, Beverly G.; Carr, Bruce R. (2000), Feingold, Kenneth R.; Anawalt, Bradley; Boyce, Alison; Chrousos, George (eds.), "The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation", Endotext, South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc., PMID 25905282, retrieved 2021-09-20

- ^ Zhang, Simeng; Osumi, Haruka; Uchizawa, Akiko; Hamada, Haruka; Park, Insung; Suzuki, Yoko; Tanaka, Yoshiaki; Ishihara, Asuka; Yajima, Katsuhiko; Seol, Jaehoon; Satoh, Makoto (2020-01-24). "Changes in sleeping energy metabolism and thermoregulation during menstrual cycle". Physiological Reports. 8 (2): e14353. doi:10.14814/phy2.14353. ISSN 2051-817X. PMC 6981303. PMID 31981319.

- ^ Kelly, Thomas (2002). "Plutarch". History: Reviews of New Books. 30 (3): 126. doi:10.1080/03612759.2002.10526169. ISSN 0361-2759. S2CID 216557803.

- ^ Wilcox, Allen J.; Baird, Donna Day; Weinberg, Clarice R. (1999-06-10). "Time of Implantation of the Conceptus and Loss of Pregnancy". New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (23): 1796–1799. doi:10.1056/NEJM199906103402304. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 10362823.

- ^ Curtis, Glade B. (1999). Your pregnancy week by week. D. F. Hawkins. Shaftesbury: Element. ISBN 1-86204-396-5. OCLC 43541212.

- ^ Holesh, Julie E.; Bass, Autumn N.; Lord, Megan (2021), "Physiology, Ovulation", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28723025, retrieved 2021-09-20

- ^ "26.6B: Ovarian Cycle". Medicine LibreTexts. 24 July 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2022.