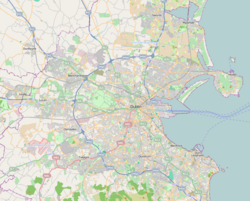

The National Botanic Gardens (Irish: Garraithe Náisiúnta na Lus) is a botanical garden in Glasnevin, 5 km north-west of Dublin city centre, Ireland.[1] The 19.5 hectares[2] are situated between Glasnevin Cemetery and the River Tolka where it forms part of the river's floodplain.

| National Botanic Gardens | |

|---|---|

| Garraithe Náisiúnta na Lus | |

| |

| Type | Botanic Garden |

| Location | Glasnevin, Dublin |

| Coordinates | 53°22′19.20″N 6°16′22.80″W / 53.3720000°N 6.2730000°W |

| Area | 19.5 ha (48 acres) |

| Created | 1795 |

| Operated by | Office of Public Works |

| Status | Open all year |

| Website | www.botanicgardens.ie |

The gardens were founded in 1795 by the Dublin Society (later the Royal Dublin Society) and are today in State ownership through the Office of Public Works.[3] They house approximately 20,000 living plants and many millions of dried plant specimens. There are several architecturally notable greenhouses. The Glasnevin site is the headquarters of the National Botanic Gardens of Ireland which has a satellite garden and arboretum at Kilmacurragh in County Wicklow.

The gardens participate in national and international initiatives for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Director of the Gardens Dr. Matthew Jebb, is also Chairman of PlantNetwork: The Plant Collections Network of Britain and Ireland. It is Ireland's seventh most visited attraction, and the second most visited free attraction.[4]

History

editPoet Thomas Tickell owned a house and small estate in Glasnevin and, in 1795, they were sold to the Irish Parliament and given to the Royal Dublin Society for them to establish Ireland's first botanic gardens. A double line of yew trees, known as "Addison's Walk" survives from this period.[5] The original function of the gardens was to advance knowledge of plants for agricultural, medicinal and dyeing purposes. The gardens were the first location in Ireland where the infection responsible for the 1845–1847 Great Famine was identified. Throughout the famine, research to stop the infection was undertaken at the gardens.

Walter Wade and John Underwood, the first Director and Superintendent respectively, executed the layout of the gardens, but, when Wade died in 1825, they declined for some years. From 1834, Director Ninian Nivan brought new life into the gardens, performing some redesign. This programme of change and development continued with the following Directors into the late 1960s.[5]

The gardens were placed into government care in 1877. That same year, Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil, visited the gardens as part of a largely unpublicised visit to Ireland.[6]

In the winter of 1948/9 Ludwig Wittgenstein lived and worked in Ireland. He frequently came to the Palm House to sit and write. There is a plaque commemorating him on the steps he sat on.[7]

Facilities

editAs well as being a tourist destination and an amenity for nearby residents, the gardens – offering free entry – serve as a centre for horticultural research and training, including the breeding of many prized orchids.

The soil at Glasnevin is strongly alkaline (in horticultural terms) and this restricts the cultivation of calcifuge plants such as rhododendrons to specially prepared areas. Nonetheless, the gardens display a range of outdoor "habitats" such as a rockery, herbaceous border, rose garden, bog garden and arboretum. A vegetable garden has also been established.

The National Herbarium is also housed at the National Botanic Gardens. The museum collection contains some 20,000 samples of plant products, including fruits, seeds, wood, fibres, plant extracts and artefacts, collected over the garden's two-hundred-year history. The gardens contain noted and historically important collections of orchids. The newly restored Palm House houses many tropical and subtropical plants. In 2002, a new multistorey complex was built; it includes a cafe and a large lecture theatre. The gardens are also responsible for the arboretum at Kilmacurragh, County Wicklow, a centre noted for its conifers and calcifuges. This is located some 50 kilometres (31 miles) south of Dublin.

A gateway into Glasnevin Cemetery adjacent to the gardens was reopened in recent years.

Architecture

editThe gardens include some glasshouses of architectural importance, such as the Palm House and the Curvilinear Range.

The Great Palm House is situated in the southern parts of the gardens, and is connected to the cactus house on its west side, and the orchid house on its east side. The main building measures 65 feet in height, 100 feet in length and 80 feet in width.

The Palm House was originally built in 1862 to accommodate the ever-increasing collection of plants from tropical areas that demanded more and more protected growing conditions. The construction was overseen by David Moore, the curator of the gardens at the time. The original structure was built of wood, and was unstable, leading to it being blown down by heavy gales in 1883, twenty-one years later. Richard Turner, the great Dublin ironmaster, had already supplied an iron house to Belfast Gardens and he persuaded the Royal Dublin Society that such a house would be a better investment than a wooden house, and by 1883 construction had begun on a stronger iron structure. Fabrication of the structure took place in Paisley, Scotland, and shipped to Ireland in sections. By the early 2000s, the Palm House had fallen into a state of disrepair. After more than 100 years, the wrought iron, cast iron and timber construction had seriously deteriorated. Prior to its restoration, a large number of panes of glass were breaking each year due to the corrosion and instability of the structure. As part of the restoration, the house was completely dismantled into more than 7,000 parts, and tagged for repair and restoration off-site. 20-metre-tall cast iron columns within the Great Palm House had seriously degraded and were replaced by new cast iron columns created in moulds of the originals. To protect the structure from further corrosion, new modern paint technology was used to develop long-term protection for the Palm House, providing protection from the perpetually tropical internal climate. For Health and Safety reasons, overhead glass was laminated and vertical panes toughened, and a specialised form of mastic was used to fix the panes, replacing the original linseed oil putty that had contributed to the decay of the building over the century. The Palm House was reopened in 2004 after a lengthy replanting programme following the restoration process.

The Curvilinear Range was completed in 1848 by Richard Turner, and was extended in the late 1860s. This structure, has also been restored (using some surplus contemporary structural ironwork from Kew Gardens) and this work attracted the Europa Nostra award for excellence in conservation architecture.[1]

There is also a third range of glasshouses: the Aquatic House, the Fern House and the original Cactus House. These structures were closed off in the early 2000s, and are currently undergoing restoration. As these glasshouses were specialised in the plants they housed, many specimens such as the Giant Amazonian Water Lily have not been grown in the gardens since the closure of the structures.

College of Amenity Horticulture (Teagasc)

editBuilding on the training and education legacy of the gardens, the Teagasc College of Amenity Horticulture is located in the gardens. It runs full- and part-time courses training students for the amenity horticulture industry. Training is run in association with the Office of Public Works (OPW), Dublin local authority parks departments, and the Golfing Union of Ireland.[8]

Directors

editThe Director is the chief officer of the Gardens, with a residence provided on site. Directors have included:[5]

- Dr Walter Wade, Professor of Botany to the Dublin Society (until 1825)

- Samuel Litton (1825–1834)

- Ninian Niven (1834–1838)

- Dr David Moore (1838–79)

- Sir Frederick William Moore (1879–1922)

- J. W. Besant (1922–44)

- Dr T. J. Walsh (1944–68)

- Aidan Brady (1968–1993)

- Donal M. Synnott (1994–2004)

- Dr Peter Wyse Jackson (2005–2010)

- Dr Matthew Jebb (2010– )

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Heritage Ireland: National Botanic Gardens". Office of Public Works. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Gartland, Fiona. "Valuable lead roofing stolen from Dublin bandstands". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ "Opening Hours | National Botanic Gardens of Ireland | The Office of Public Works". Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ^ "Guinness Storehouse tops list of most visited attractions". Irish Times. 26 July 2013. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ a b c "National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin". Irelandseye.com. 1999–2005. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ^ "Dom Pedro II in Ireland" (PDF). assets.ireland.ie. Consulate General of Ireland - São Paulo. 21 May 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ "Ludwig Wittgenstein's Dublin memorials". Come Here To Me!. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ College of Amenity Horticulture - Botanic Gardens Archived 6 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine www.teagasc.ie