Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (Russian: Илья Ильич Мечников; 15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1845 – 15 July 1916), also spelled Élie Metchnikoff,[2][note 1] was a zoologist from the Russian Empire of Moldavian[3][4][5][6][7] noble ancestry[8] best known for his pioneering research in immunology (study of immune systems) and thanatology (study of death).[9][10][11][12] He and Paul Ehrlich were jointly awarded the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "in recognition of their work on immunity".[13]

Élie Metchnikoff | |

|---|---|

Илья Мечников | |

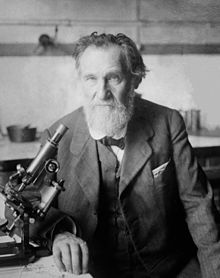

Metchnikoff c. 1910–1915 | |

| Born | Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1845 |

| Died | 15 July 1916 (aged 71) Paris, France |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

Mechnikov was born in a region of the Russian Empire that is today part of modern-day Ukraine to a Moldavian noble father[4] and a Ukrainian-Jewish mother,[14] and later on continued his career in France. Given this complex heritage, five different nations and peoples lay claim to Metchnikoff.[15] Despite having a mother of Jewish origin, he was baptized Russian Orthodox, although he later became an atheist.

Honoured as the "father of innate immunity",[16][17] Metchnikoff was the first to discover a process of immunity called phagocytosis and the cell responsible for it, called phagocyte, specifically macrophage, in 1882. This discovery turned out to be the major defence mechanism in innate immunity,[18] as well as the foundation of the concept of cell-mediated immunity, while Ehrlich established the concept of humoral immunity to complete the principles of immune system. Their works are regarded as the foundation of the science of immunology.[19]

Metchnikoff developed one of the earliest concepts in ageing, and advocated the use of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus) for healthy and long life. This became the concept of probiotics in medicine.[20] Mechnikov is also credited with coining the term gerontology in 1903, for the emerging study of aging and longevity.[21][22] In this regard, Ilya Mechnikov is called the "father of gerontology"[23][24] (although, as often happens in science, the situation is ambiguous, and the same title is sometimes applied to some other people who contributed to aging research later).

Supporters of life extension celebrate 15 May as Metchnikoff Day, and used it as a memorable date for organizing activities.[25][26]

Early life, family and education

editMetchnikoff was born in the village of Ivanovka, Kharkov Governorate, in the Russian Empire, now located in Kupiansk Raion, Kharkiv Oblast in Ukraine. He was the youngest of five children of Ilya Ivanovich Mechnikov, an officer of the Imperial Guard.[12] His mother, Emilia Lvovna (Nevakhovich), the daughter of the writer Leo Nevakhovich, largely influenced him on his education, especially in science.[27][8] The Nevakhovich family was Jewish.[12]

The family name Mechnikov is a translation from Romanian, since his father was a descendant of the Chancellor Yuri Stefanovi, the grandson of Nicolae Milescu Spătarul. Yuri Stefanovich emigrated to Russia together with Dimitrie Cantemir in 1711 after the unsuccessful campaign of Peter I on the Danubian Principalities. For two and a half centuries, the Mechnikov family lived in St. Petersburg, where it became connected by family ties with many Russian princely families. The word "mech" is a Russian translation of the Romanian "spadă" (sword), which originated with Spătar (Sword-bearer). His elder brother Lev became a prominent geographer and sociologist.[28]

In 1856, Metchnikoff entered the Kharkov Lycée, where he developed his interest in biology. Convinced by his mother to study natural sciences instead of medicine, in 1862 he tried to study biology at the University of Würzburg, but the German academic session would not start by the end of the year. Metchnikoff thus enrolled at Kharkov Imperial University for natural sciences, completing his four-year degree in two years.

In 1864, he traveled to Germany to study marine fauna on the small North Sea island of Heligoland. He was advised by the botanist Ferdinand Cohn to work with Rudolf Leuckart at the University of Giessen. It was in Leuckart's laboratory that he made his first scientific discovery of alternation of generations (sexual and asexual) in nematodes (Chaetosomatida) and then at the University of Munich. In 1865, while at Giessen, he discovered intracellular digestion in flatworm, and this study influenced his later works. Moving to Naples the next year he worked on a doctoral thesis on the embryonic development of the cuttle-fish Sepiola and the crustacean Nebalia. A cholera epidemic in the autumn of 1865 made him move to the University of Göttingen, where he worked briefly with W. M. Keferstein and Jakob Henle.

In 1867, he returned to Russia to receive his doctorate with Alexander Kovalevsky from the University of Saint Petersburg. Together they won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize for their theses on the development of germ layers in invertebrate embryos.

Career and achievements

editMetchnikoff was appointed docent at the newly established Imperial Novorossiya University (now Odesa University). Only twenty-two years of age, he was younger than his students. After being involved in a conflict with a senior colleague over attending scientific meetings, he transferred to the University of Saint Petersburg in 1868, where he experienced a worse professional environment. In 1870 he returned to Odessa to take up the appointment of Titular Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy.[12][27]

In 1882 he resigned from Odessa University due to political turmoils after the assassination of Alexander II. He went to Sicily to set up his private laboratory in Messina. He returned to Odessa as director of an institute set up to carry out Louis Pasteur's vaccine against rabies; due to some difficulties, he left in 1888 and went to Paris to seek Pasteur's advice. Pasteur gave him an appointment at the Pasteur Institute, where he remained for the rest of his life.[12]

Metchnikoff became interested in the study of microbes, and especially the immune system. At Messina he discovered phagocytosis after experimenting on the larvae of starfish. In 1882 he first demonstrated the process when he inserted small citrus thorns into starfish larvae, then found unusual cells surrounding the thorns. He realized that in animals which have blood, the white blood cells gather at the site of inflammation, and he hypothesised that this could be the process by which bacteria were attacked and killed by the white blood cells. He discussed his hypothesis with Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Claus, Professor of Zoology at the University of Vienna, who suggested to him the term "phagocyte" for a cell which can surround and kill pathogens. He delivered his findings at Odessa University in 1883.[12]

His theory, that certain white blood cells could engulf and destroy harmful bodies such as bacteria, met with scepticism from leading specialists including Louis Pasteur, Emil von Behring, and others. At the time, most bacteriologists believed that white blood cells ingested pathogens and then spread them further through the body. His major supporter was Rudolf Virchow, who published his research in his Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin (now called the Virchows Archiv).[27] His discovery of these phagocytes ultimately won him the Nobel Prize in 1908.[13] He worked with Émile Roux on calomel (mercurous chloride) in ointment form in an attempt to prevent people from contracting the sexually transmitted disease syphilis.[29]

In 1887, he observed that leukocytes isolated from the blood of various animals were attracted towards certain bacteria.[30] The first studies of leukocyte killing in the presence of specific antiserum were performed by Joseph Denys and Joseph Leclef, followed by Leon Marchand and Mennes between 1895 and 1898. Almoth E. Wright was the first to quantify this phenomenon and strongly advocated its potential therapeutic importance. The so-called resolution of the humoralist and cellularist positions by showing their respective roles in the setting of enhanced killing in the presence of opsonins was popularized by Wright after 1903, although Metchnikoff acknowledged the stimulatory capacity of immunosensitized serum on phagotic function in the case of acquired immunity.[31]

This attraction was soon proposed to be due to soluble elements released by the bacteria[32] (see Harris[33] for a review of this area up to 1953). Some 85 years after this seminal observation, laboratory studies showed that these elements were low molecular weight (between 150 and 1500 Dalton (unit)s) N-formylated oligopeptides, including the most prominent member of this group, N-Formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine, that are made by a variety of replicating gram positive bacteria and gram negative bacteria.[34][35][36][37] Metchnikoff's early observation, then, was the foundation for studies that defined a critical mechanism by which bacteria attract leukocytes to initiate and direct the innate immune response of acute inflammation to sites of host invasion by pathogens.[16][17]

Metchnikoff discovered fungal infections causing insect death in 1879 and became involved in the biological control of insect pests through his student Isaak Krasilschik. They were able to make use of green muscardine for control of insects in agricultural fields.[38][39]

Metchnikoff also self-experimented with cholera that initially supported the probiotic notion. During the 1892 cholera epidemic in France, he was surprised by the fact that the disease affected only some people but not others when they were equally exposed to the infection. To understand the differences in susceptibility to the disease, he drank a sample of cholera but never got sick. He tested on two volunteers of which one was not affected while the other almost died. He hypothesised that the difference in cholera infection was due to differences in intestinal microbes, speculating that those who have plenty of beneficial ones would be healthier.[40]

The issues of aging occupied a significant place in Metchnikoff's works.[41] Metchnikoff developed a theory that aging is caused by toxic bacteria in the gut and that lactic acid could prolong life. He attributed the longevity of Bulgarian peasants to their yogurt consumption[42] that contained what was called the Bulgarian bacteria (now called Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus).[20] To validate his theory, he drank sour milk every day throughout his life. His scientific reasonings on the subject were written in his books The Nature of Man: Studies in Optimistic Philosophy (1903) and more expressively in The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies (1907).[43] He also espoused the potential life-lengthening properties of lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus.[44] This concept of probiotics, which he termed "orthobiosis,"[43] was influential in his lifetime, but became ignored until the mid-1990s when experimental evidence emerged.[20][45]

Awards and recognitions

editMetchnikoff won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize in 1867 with Alexander Kovalevsky based on their doctoral research. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908 with Paul Ehrlich . He was awarded honorary degree from the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, UK, and the Copley Medal of the Royal Society in 1906. He was given honorary memberships in the Academy of Medicine in Paris and the Academy of Sciences and Medicine in Saint Petersburg.[46] The Leningrad Medical Institute of Hygiene and Sanitation, founded in 1911 was merged with Saint Petersburg State Medical Academy of Postgraduate Studies in 2011 to become the North-Western State Medical University, named after Metchnikoff.[47][48] The Odesa I. I. Mechnikov National University is in Odesa, Ukraine.[49]

Personal life and views

editMetchnikoff married his first wife, Ludmila Feodorovitch, in 1869. She died from tuberculosis on 20 April 1873. Her death, combined with other problems, caused Metchnikoff to attempt suicide, taking a large dose of opium. In 1875, he married his student Olga Belokopytova.[50] In 1885 Olga suffered from severe typhoid and this led to his second suicide attempt.[12] He injected himself with the spirochete of relapsing fever. (Olga died in 1944 in Paris from typhoid.)[27]

Despite being baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church, Metchnikoff was an atheist.[51]

He was greatly influenced by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. He first read Fritz Müller's Für Darwin (For Darwin) in Giessen. From this he became a supporter of natural selection and Ernst Haeckel's biogenetic law.[46] His scientific works and theories were inspired by Darwinism.[52]

Metchnikoff died in 1916 in Paris from heart failure.[53] According to his will, his body was used for medical research and afterwards cremated in Père Lachaise Cemetery crematorium. His cinerary urn has been placed in the Pasteur Institute library.[54]

Publications

editMetchnikoff wrote notable books and papers, including:[18][50]

- Leçons sur la pathologie comparée de l’inflammation (1892; Lectures on the Comparative Pathology of Inflammation)

- L’Immunité dans les maladies infectieuses (1901; Immunity in Infectious Diseases)

- Études sur la nature humaine (1903; The Nature of Man)

- Immunity in Infective Diseases (1905)

- The New Hygiene: Three Lectures on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases (1906)

- The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies (1907)

- "Этюды оптимизма" [Etudes of Optimism]. Научного слова [Scientific Word] (2nd ed.). Moscow. 1909.

- "Этюды о природе человека" [Etudes About Human Nature]. Научного слова [Scientific Word] (4th ed.). Moscow. 1913 – via psychlib.ru.

- "Основатели современной медицины. Пастер — Листер — Кох" [The Founders of Modern Medicine: Pasteur - Lister - Koch]. Научного слова. Moscow. 1915 – via dlib.rsl.ru.

Explanatory notes

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ Racine, Valerie, "Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (Élie Metchnikoff) (1845-1916)". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2014-07-05). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/8018.

- ^ a b "Ilya Mechnikov: Biographical". Nobel Prizes. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Vaughan, R. B. (July 1965). "The Romantic Rationalist a Study of Elie Metchnikoff". Medical History. 9 (3): 201–215. doi:10.1017/S0025727300030702. ISSN 2048-8343. PMC 1033501. PMID 14321564.

- ^ a b Stambler, Ilia (1 October 2015). "Elie Metchnikoff—The founder of longevity science and a founder of modern medicine: In honor of the 170th anniversary". Advances in Gerontology. 5 (4): 201–208. doi:10.1134/S2079057015040219. ISSN 2079-0589. S2CID 35017226.

- ^ O'Donoghue, Chas. H. (1916). "Élie Metchnikoff". Science Progress (1916-1919). 11 (42): 308–310. ISSN 2059-495X. JSTOR 43426778.

- ^ Riesman, David (September 1922). "Life of Elie Metchnicoff". Annals of Medical History. 4 (3): 317–319. ISSN 0743-3131. PMC 7034616.

- ^ Ezepchuk, Yu V.; Kolybo, D. V. (2016). "Nobel Laureate Ilya I. Mechnikov (1845-1916). Life story and career". The Ukrainian Biochemical Journal. 88 (88, № 6): 98–109. doi:10.15407/ubj88.06.098. ISSN 2409-4943. PMID 29236381.

- ^ a b Metchnikoff, Olga (1921). Life of Elie Metchnikoff, 1845-1916. Houghton Mifflin Company – via gutenberg.org. and also here at archive.org

- ^ Metchnikoff, Elie (Encyclopedia. Oxford University Press)

- ^ Belkin, R.I. (1964). "Commentary," in I.I. Mechnikov, Academic Collection of Works, vol. 16. Moscow: Meditsina. p. 434. Belkin, a Russian science historian, explains why Metchnikoff himself, in his Nobel autobiography – and subsequently, many other sources – mistakenly cited his date of birth as 16 May instead of 15 May. Metchnikoff made the mistake of adding 13 days to 3 May, his Old Style birthday, as was the convention in the 20th century. But since he had been born in the 19th century, only 12 days should have been added.

- ^ Vikhanski, Luba (2016). Immunity: How Elie Metchnikoff Changed the Course of Modern Medicine. Chicago Review Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-1613731109.

The author cites Metchnikoff's death certificate, according to which he died on July 15, 1916 (the original is in the Archive of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Metchnikoff Fund, 584-2-208). Olga Metchnikoff did not provide a precise date for her husband's death in her book, and many sources erroneously cite it as July 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ilya Mechnikov – Biographical". nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1908". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Kurlansky, Mark (5 September 2019). Milk: A 10,000-Year History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1526614353. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Stambler, Ilia (13 December 2020). "Ilya Mechnikov — the founder of Gerontology" (PDF). The East Europe Journal of Internal and Family Medicine. 2B (14). Kharkov: 29–30. doi:10.15407/internalmed2020.02b.029.

- ^ a b Gordon, Siamon (2008). "Elie Metchnikoff: father of natural immunity". European Journal of Immunology. 38 (12): 3257–3264. doi:10.1002/eji.200838855. PMID 19039772.

- ^ a b Gordon, Siamon (2016). "Elie Metchnikoff, the Man and the Myth". Journal of Innate Immunity. 8 (3): 223–227. doi:10.1159/000443331. PMC 6738810. PMID 26836137.

- ^ a b "Élie Metchnikoff". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ Kaufmann, Stefan H E (2008). "Immunology's foundation: the 100-year anniversary of the Nobel Prize to Paul Ehrlich and Elie Metchnikoff". Nature Immunology. 9 (7): 705–712. doi:10.1038/ni0708-705. PMID 18563076. S2CID 205359637.

- ^ a b c Mackowiak, Philip A. (2013). "Recycling metchnikoff: probiotics, the intestinal microbiome and the quest for long life". Frontiers in Public Health. 1: 52. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00052. PMC 3859987. PMID 24350221.

- ^ Vértes, L (1985). "The gerontologist Mechnikov". Orvosi Hetilap. 126 (30): 1859–1860. PMID 3895124.

- ^ Martin, D. J.; Gillen, L. L. (2013). "Revisiting Gerontology's Scrapbook: From Metchnikoff to the Spectrum Model of Aging". The Gerontologist. 54 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt073. PMID 23893558.

- ^ Vikhanski, L. (1 November 2016). "Elie Metchnikoff Rediscovered: Comeback of a Founding Father of Gerontology". The Gerontologist. 56 (Suppl_3): 181. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw162.708.

- ^ Stambler, Ilia (29 August 2014). ""Father" Metchnikoff". A History of Life-Extensionism in the Twentieth Century. Longevity History. p. 540. ISBN 978-1500818579.

- ^ Stambler, Ilia; Milova, Elena (2019), "Longevity Activism", in Gu, Danan; Dupre, Matthew E. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69892-2_395-1, ISBN 978-3-319-69892-2, S2CID 239107136, retrieved 13 May 2021

- ^ "Metchnikoff Day, an Opportunity to Promote the Study of Aging and Longevity". Fight Aging!. 15 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Metchnikoff, Elie". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ White, James D (1976). "Despotism and Anarchy: The Sociological Thought of L. I. Mechnikov". The Slavonic and East European Review. 54 (3): 395–411. JSTOR 4207300.

- ^ Worms, Werner (1940). "Prophylaxis of Syphilis by Locally Applied Chemicals. Methods of Examination, Results, and Suggestions for Further Experimental Research". British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 16 (3–4): 186–210. doi:10.1136/sti.16.3-4.186. PMC 1053233. PMID 21773301.

- ^ Metchnikoff E (1887). "Sur la lutte des cellules de l'organisme contre l'invasion des microbes". Annales de l'Institut Pasteur. 1: 321.

- ^ Tauber& Cherniak (1991). Metchnikoff and the Origins of Immunology: From Metaphor to Theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-19-506447-X.

- ^ Grawitz P (1887). "unknown title". Virchows Adz. IIO. I.

- ^ Harris H (July 1954). "Role of chemotaxis in inflammation". Physiological Reviews. 34 (3): 529–62. doi:10.1152/physrev.1954.34.3.529. PMID 13185754.

- ^ Ward PA, Lepow IH, Newman LJ (April 1968). "Bacterial factors chemotactic for polymorphonuclear leukocytes". The American Journal of Pathology. 52 (4): 725–36. PMC 2013377. PMID 4384494.

- ^ J Exp Med. 1976 May 1;143(5):1154–69.

- ^ J Immunol. 1974 Jun;112(6):2055–62.

- ^ Schiffmann E, Showell HV, Corcoran BA, Ward PA, Smith E, Becker EL (June 1975). "The isolation and partial characterization of neutrophil chemotactic factors from Escherichia coli". Journal of Immunology. 114 (6): 1831–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.114.6.1831. PMID 165239. S2CID 22663271.

- ^ Zimmermann, Gisbert; Papierok, Bernard; Glare, Travis (1995). "Elias Metschnikoff, Elie Metchnikoff or Ilya Ilich Mechnikov (1845-1916): A Pioneer in Insect Pathology, the First Describer of the Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium anisopliae and How to Translate a Russian Name". Biocontrol Science and Technology. 5 (4): 527–530. Bibcode:1995BioST...5..527Z. doi:10.1080/09583159550039701. ISSN 0958-3157.

- ^ Timuș, Asea (2015). "Secvenţe din istoria cercetării filoxerei viţei-de-vie în Basarabia" (PDF). Enciclopedica. Revistă de istorie a știinţei și studii enciclopedice. 2 (9): 8–18.

- ^ Lewis, Danny (7 May 2015). "Probiotics Exist Thanks to a Man Who Drank Cholera". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Elena Milova (12 May 2017). "Commemorating the Work of Dr. Elie Metchnikoff". Lifespan.io. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Brown, AC; Valiere, A (2004). "Probiotics and medical nutrition therapy". Nutrition in Clinical Care. 7 (2): 56–68. PMC 1482314. PMID 15481739.

- ^ a b Podolsky, Scott H (2012). "Metchnikoff and the microbiome". The Lancet. 380 (9856): 1810–1811. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62018-2. PMID 23189332. S2CID 13290396.

- ^ Mackowiak, Philip A. (2013). "Recycling Metchnikoff: Probiotics, the Intestinal Microbiome and the Quest for Long Life". Frontiers in Public Health. 1: 52. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00052. PMC 3859987. PMID 24350221.

- ^ Gasbarrini, Giovanni; Bonvicini, Fiorenza; Gramenzi, Annagiulia (2016). "Probiotics History". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 50 (Suppl 2): S116 – S119. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000697. PMID 27741152.

- ^ a b "Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (Elie Metchnikoff) (1845–1916)". The Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ "North-Western State Medical University I.I. Mechnikov". FAIMER. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov". North-Western State Medical University named after I.I. Mechnikov. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "Odessa I.I. Mechnikov national university". Odessa I.I. Mechnikov national university. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b Gordon, Siamon (2008). "Elie Metchnikoff: Father of natural immunity". European Journal of Immunology. 38 (12): 3257–3264. doi:10.1002/eji.200838855. PMID 19039772. S2CID 658489.

- ^ Tauber, Alfred I.; Chernyak, Leon (1991). Metchnikoff and the Origins of Immunology: From Metaphor to Theory: From Metaphor to Theory. New York (US): Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-1953451-00.

There is no clear record that he was professionally restricted in Russia because of his lineage, but he sympathized with the problem his Jewish colleagues suffered owing to Russian anti-Semitism; his personal religious commitment was to atheism, although he received strict Christian religious training at home. Metchnikoff's atheism smacked of religious fervor in the embrace of rationalism and science. We may fairly argue that Metchnikoff's religion was based on the belief that rational scientific discourse was the solution for human suffering.

- ^ Thomas F., Glick (1988). The Comparative Reception of Darwinism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-226-29977-8.

- ^ Goldstein, B. I. (21 July 1916). "Elie Metchnikoff". Canadian Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ "Мечников Илья Ильич (1845-1916)" [Mechnikov Ilya Ilyich (1845-1916)]. m-necropol.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 26 May 2021.

Further reading

edit- Breathnach, C S (September 1984). "Biographical sketches—No. 44. Metchnikoff". Irish Medical Journal. 77 (9). Ireland: 303. ISSN 0332-3102. PMID 6384135.

- de Kruif, Paul (1996). Microbe Hunters (Reprint ed.). San Diego: A Harvest Book; Harcourt. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-15602-777-9.

- de Kruif, Paul (1926). "VII Metchnikoff: The Nice Phagocytes". Microbe Hunters. Blue Ribbon Books. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company Inc. pp. 207–233. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Deutsch, Ronald M. (1977). The new nuts among the berries. Palo Alto, CA: Bull Pub. Co. ISBN 0-915950-08-1.

- Fokin, Sergei I. (2008). Russian scientists at the Naples zoological station, 1874–1934. Napoli: Giannini. ISBN 978-8-8743-1404-1.

- Gourko, Helena; Williamson, Donald I.; Tauber, Alfred I. (2000). The Evolutionary Biology Papers of Elie Metchnikoff. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-015-9381-6.

- Karnovsky, M L (May 1981). "Metchnikoff in Messina: a century of studies on phagocytosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 304 (19). United States: 1178–80. doi:10.1056/NEJM198105073041923. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 7012622.

- Lavrova, L N (September 1970). "[I. I. Mechnikov and the significance of his legacy for the development of Soviet science (on the 125th anniversary of his birth)]". Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 47 (9). USSR: 3–5. ISSN 0372-9311. PMID 4932822.

- Schmalstieg Frank C, Goldman Armond S (2008). "Ilya Ilich Metchnikoff (1845–1915) and Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915) The centennial of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine". Journal of Medical Biography. 16 (2): 96–103. doi:10.1258/jmb.2008.008006. PMID 18463079. S2CID 25063709.

- Tauber AI (2003). "Metchnikoff and the phagocytosis theory". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 4 (11): 897–901. doi:10.1038/nrm1244. PMID 14625539. S2CID 4571282.

- Tauber, Alfred I.; Chernyak, Leon (1991). Metchnikoff and the Origins of Immunology: From Metaphor to Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534510-0.

- Zalkind, Semyon (2001) [1957]. Ilya Mechnikov: His Life and Work. The Minerva Group, Inc. ISBN 0-89875-622-7.

External links

edit- The Romantic Rationalist: A Study Of Elie Metchnikoff

- Works of Elie Metchnikoff, a Pasteur Institute bibliography

- Books written by I.I.Mechnikov (In Russian)

- Lactobacillus bulgaricus on the web

- Tsalyk St. Immunity defender Archived 18 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Immunity in Infective Diseases (1905) by Élie Metchnikoff, translated by Francis B. Binny, on the Internet Archive

- The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies (1908) by Élie Metchnikoff, translation edited by P. Chalmers Mitchell, on the Internet Archive

- Luba Vikhanski's page for Metchnikoff's documentary

- Mechnikov Ilya, 1845 - 1916, Year won 1908, A pioneer researcher of immunity on the ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

- Ilya Mechnikov on Nobelprize.org