Ilya Grigoryevich Ehrenburg (Russian: Илья́ Григо́рьевич Эренбу́рг, pronounced [ɪˈlʲja ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲjɪvɪtɕ ɪrʲɪnˈburk] ; January 26 [O.S. January 14] 1891 – August 31, 1967) was a Soviet writer, revolutionary, journalist and historian.

Ilya Ehrenburg | |

|---|---|

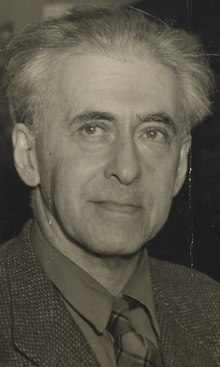

Ehrenburg in 1959 | |

| Born | January 26 [O.S. January 14] 1891 Kiev, Russian Empire |

| Died | August 31, 1967 (aged 76) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Notable works | Julio Jurenito, The Thaw |

| Signature | |

| |

Ehrenburg was among the most prolific and notable authors of the Soviet Union; he published around one hundred titles. He became known first and foremost as a novelist and a journalist – in particular, as a reporter in three wars (First World War, Spanish Civil War and the Second World War). His incendiary articles calling for violence against Germans during the Great Patriotic War won him a huge following among front-line Soviet soldiers, but also caused much controversy due to their perceived anti-German sentiment. Ehrenburg later clarified that his writings were about "German aggressors who set foot on Soviet soil with weapons", not the whole German people.

The novel The Thaw gave its name to an entire era of Soviet politics, namely, the liberalization which occurred after the death of Joseph Stalin. Ehrenburg's travel writing also had great resonance, and to an arguably greater extent, so did his memoir People, Years, Life, which may be his best known and most discussed work. The Black Book, edited by him and Vasily Grossman, has special historical significance, it describes the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, the genocide which was committed against Soviet citizens of Jewish ancestry by the Nazis; It was denounced as "anti-Soviet" and banned from publication.[1] It was first published in Jerusalem in 1980.

In addition, Ehrenburg wrote a succession of works of poetry.

Life and work

editIlya Ehrenburg was born in Kiev, Ukraine, in the Russian Empire to a Lithuanian-Jewish family; his father was an engineer. Ehrenburg's household was not religiously observant; he came into contact with the religious practices of Judaism only through his maternal grandfather. Ehrenburg never practiced Judaism. He learned no Yiddish, although he edited the Black Book, which was written in Yiddish. He considered himself a Russian and, later, a Soviet citizen, and wrote in Russian even during his many years abroad. Ehrenburg also took strong public positions against antisemitism, and left all his papers to Israel's Yad Vashem.[citation needed]

When Ehrenburg was four years old, the family moved to Moscow, where his father had been hired as director of a brewery.[2] At school, he met Nikolai Bukharin, who was two grades above him.[3] The two remained friends until Bukharin's execution in 1938 during the Great Purge.[4]

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1905, both Ehrenburg and Bukharin got involved in illegal activities of the Bolshevik organisation.[5] In 1908, when Ehrenburg was seventeen years old, the tsarist secret police (Okhrana) arrested him for five months. He was beaten up and lost some teeth. Finally he was allowed to go abroad and chose Paris for his exile.[6]

In Paris, he started to work in the Bolshevik organisation, meeting Vladimir Lenin and other prominent exiles. But soon he left these circles and the party. Ehrenburg became attached to the bohemian life in the Paris quarter of Montparnasse. He began to write poems, regularly visited the cafés of Montparnasse and got acquainted with a lot of artists, especially Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Jules Pascin, and Amedeo Modigliani. Foreign writers whose works Ehrenburg translated included those of Francis Jammes.

During World War I, Ehrenburg became a war correspondent for a St. Petersburg newspaper. He wrote a series of articles about the mechanized war that later on were also published as a book (The Face of War). His poetry now also concentrated on subjects of war and destruction, as in On the Eve, his third lyrical book. Nikolai Gumilev, a famous symbolistic poet, wrote favourably about Ehrenburg's progress in poetry.

In 1917, after the revolution, Ehrenburg returned to Russia. At that time he tended to oppose the Bolshevik policy, being shocked by the constant atmosphere of violence. He wrote a poem called "Prayer for Russia" which compared the storming of the Winter Palace to rape. In 1920 Ehrenburg went to Kiev where he experienced four different regimes in the course of one year: the Germans, the Cossacks, the Bolsheviks, and the White Army. After antisemitic pogroms, he fled to Koktebel on the Crimea peninsula where his old friend from Paris days, Maximilian Voloshin, had a house. Finally, Ehrenburg returned to Moscow, where he soon was arrested by the Cheka but freed after a short time.

He became a Soviet cultural activist and journalist who spent much time abroad as a writer. He wrote avant-garde picaresque novels and short stories popular in the 1920s, often set in Western Europe (The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples (1922), Thirteen Pipes[7]). Ehrenburg continued to write philosophical poetry, using more freed rhythms than in the 1910s. In 1929 he published The Life of the Automobile, a communist variant of the it-narrative genre.[8]

In 1935, Ehrenburg attended the first International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, which opened in Paris in June. He had written a pamphlet which said, among other things, that surrealists shunned work, favouring parasitism, and that they endorsed "onanism, pederasty, fetishism, exhibitionism, and even sodomy". André Breton — along with all fellow surrealists — felt insulted and accosted Ehrenburg on the street and slapped him several times, which resulted in surrealists being expelled from the Congress.[9]

Spanish Civil War

editAs a friend of many of the European Left, Ehrenburg was frequently allowed by Stalin to visit Europe and to campaign for peace and socialism. He arrived in Spain in late August 1936 as an Izvestia correspondent and was involved in propaganda and military activity as well as reporting.[10] In July 1937 he attended the Second International Writers' Congress, the purpose of which was to discuss the attitude of intellectuals to the war, held in Valencia, Barcelona, and Madrid and attended by many writers including André Malraux, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Spender, and Pablo Neruda.[11]

World War II

editEhrenburg was offered a column in Krasnaya Zvezda (the Red Army newspaper) days after the German invasion of the Soviet Union. During the war, he published more than 2,000 articles in Soviet newspapers.[12] He saw the Great Patriotic War as a dramatic contest between good and evil. In his articles, moral and life-affirming Red Army soldiers faced off against a dehumanized German enemy.[13] In 1943, Ehrenburg, working with the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, began to collect material for what would become The Black Book of Soviet Jewry, documenting The Holocaust. In a December 1944 article in Pravda, Ehrenburg declared that the Germans' greatest crime was the murder of six million Jews.[12]

His incendiary articles calling for vengeance against the German enemy won him a huge following among front-line Soviet soldiers, who sent him much fan mail.[14][15] As a consequence, he is one of many Soviet writers, along with Konstantin Simonov and Alexey Surkov, who many have accused of "[lending] their literary talents to the hate campaign" against Germans.[16] Austrian historian Arnold Suppan argued that Ehrenburg "agitated in the style of Nazi racist ideology", with statements such as:

The Germans are not humans. […] From now on, the word German causes gunfire. We shall not speak. We shall kill. If during a day you have not killed a single German, you have wasted the day. […] If you do not kill the German, he will kill you. […] If it is quiet at your section of the front and you are waiting for the battle, kill a German before the battle. If you let the German live, he will kill a Russian man and rape a Russian woman. If you have killed a German, kill another one too. […] Kill the German, thus cries your homeland.[17]

This pamphlet, titled "Kill", was written during the Battle of Stalingrad.[18] Ehrenburg later accompanied the Soviet forces during the East Prussian Offensive and criticized the indiscriminate violence against German civilians, for which he was reprimanded by Stalin.[13] However, his previous writings had already been interpreted as license for atrocities against German civilians during the Soviet invasion of Germany in 1945.[19] Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels accused Ehrenburg of advocating the rape of German women. However, Ehrenburg denied this and historian Antony Beevor claims that it was a Nazi fabrication.[20][14] In January 1945, Adolf Hitler stated that "Stalin's court lackey, Ilya Ehrenburg, declares that the German people must be exterminated".[13] After criticism by Georgy Aleksandrov in Pravda in April 1945,[21] Ehrenburg responded that he never meant wiping out the German people, but only German aggressors who set foot on Soviet soil with weapons, because "we are not Nazis who fight with civilians”.[22] Ehrenburg fell into disgrace at that time and it is estimated that Aleksandrov's article was a signal of change in Stalin's policy towards Germany.[23][24]

The 'Anti-Cosmopolitan' Campaign

editOn 21 September 1948, at the behest of Politburo members Lazar Kaganovich and Georgy Malenkov, Ehrenburg published an article in Pravda[25] which signified Stalin's absolute political break with Israel, which he had been supporting through enormous shipments of Czech arms.[26] After this break with Israel, hundreds of Jews became targets of the so-called anti-cosmopolitan campaign. The chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Solomon Mikhoels, was murdered, and many Soviet Jewish intellectuals were imprisoned or executed.

Ilya Ehrenburg's name was high on a list presented to Stalin by the chief of police, Viktor Abakumov, of people selected for arrest. He was accused of having "made attacks on Comrade Stalin" when talking to the French writer André Malraux in Spain in 1937. While Stalin agreed to the arrests of most of the names on the list, he put a question mark by Ehrenburg's.[27] It appears that Ehrenburg was allowed to continue publishing and travelling abroad to obscure the anti-Semitic campaign at home.[citation needed] During a press conference in London in 1950, attended by over 200 journalists, he was challenged about the fate of the writers David Bergelson and Itzik Feffer, and said that "If anything unpleasant had happened to them, I would have known", knowing that they were both under arrest.[28] He was accused of informing on his comrades, but there is no evidence to support this theory.[citation needed] In February 1953, he refused to denounce the supposed doctors' plot and wrote a letter to Stalin opposing collective punishment of Jews.[12]

Postwar writings

editEhrenburg received the Stalin Peace Prize in 1948.[29]

In 1954, Ehrenburg published a novel titled The Thaw that tested the limits of censorship in the post-Stalin Soviet Union. It portrayed a corrupt and despotic factory boss, a "little Stalin", and told the story of his wife, who increasingly feels estranged from him, and the views he represents. In the novel, the spring thaw comes to represent a period of change in the characters' emotional journeys, and when the wife eventually leaves her husband, this coincides with the melting of the snow. Thus, the novel can be seen as a representation of the thaw, and the increased freedom of the writer after the 'frozen' political period under Stalin. In August 1954, Konstantin Simonov attacked The Thaw in articles published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, arguing that such writings are too dark and do not serve the Soviet state.[30] The novel gave its name to the Khrushchev Thaw.

Ehrenburg is particularly well known for his memoirs (People, Years, Life in Russian, published with the title Memoirs: 1921–1941 in English), which contain many portraits of interest to literary historians and biographers. In this book, Ehrenburg was the first legal Soviet author to mention positively a lot of names banned under Stalin, including Marina Tsvetaeva. At the same time he disapproved of the Russian and Soviet intellectuals who had explicitly rejected communism or defected to the West. He also criticized writers like Boris Pasternak, author of Doctor Zhivago, for not having been able to understand the course of history.

Ehrenburg's memoirs were criticized by the more conservative faction among the Soviet writers, concentrated around the journal Oktyabr. For example, when the memoirs were published, Vsevolod Kochetov reflected on certain writers who were "burrowing in the rubbish heaps of their crackpot memories".[31] In January 1963, the critic Vladimir Yermilov wrote a long article in Izvestia in which he picked up on Ehrenburg's admission that he had suspected that innocent people were being arrested in 1937 and 1938 but had "gritted his teeth" in silence.

Yermilov alleged that this proved that Ehrenburg had been in a privileged position in those years but said nothing, when others, less privileged, had spoken out when they believed an innocent person had been arrested. Ehrenburg retorted that he had never been to a single meeting nor read a single article in which anyone had protested about the arrests, whereupon Yermilov accused him of having insulted a "whole generation of Soviet people".[32]

For the contemporary reader though, the work appears to have a distinctly Marxist-Leninist ideological flavor characteristic of a Soviet-era official writer.[citation needed]

He was also active in publishing the works by Osip Mandelstam when the latter had been posthumously rehabilitated but still largely unacceptable for censorship. Ehrenburg was also active as a poet till his last days, depicting the events of World War II in Europe, the Holocaust and the destinies of Russian intellectuals.

Death and Legacy

editEhrenburg died in 1967 of prostate and bladder cancer, and was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where his gravestone is etched with a reproduction of his portrait drawn by his friend Pablo Picasso.[citation needed]

In 1968, Polish-American writer and journalist S.L. Shneiderman published a Yiddish biography of Ehrenburg, whom he had met in interwar Paris and in Spain. In his biography, Shneiderman defended Ehrenburg from accusations of collaboration with Stalin in the destruction of Soviet Yiddish culture.[33][34][35]

English translations

edit- The Love of Jeanne Ney, Doubleday, Doran and Company 1930.

- The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Disciples, Covici Friede, NY, 1930.

- A Soviet Writer Looks at Vienna, Lawrence, London, 1934.

- The Fall of Paris, Knopf, NY, 1943. [novel]

- The Tempering of Russia, Knopf, NY, 1944.

- European Crossroad: A Soviet Journalist In the Balkans, Knopf, NY, 1947.

- The Storm, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1948.

- The Thaw, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1955.

- The Ninth Wave, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1955.

- The Stormy Life of Lasik Roitschwantz, Polyglot Library, 1960.[36]

- A Change of Season, (includes The Thaw and its sequel The Spring), Knopf, NY, 1962.

- Chekhov, Stendhal and Other Essays, Knopf, NY, 1963.

- Memoirs: 1921–1941, World Pub. Co., Cleveland, 1963.[37]

- Life of the Automobile, URIZEN BOOKS Joachim Neugroeschel translator 1976.

- The Second Day, Raduga Publishers, Moscow, 1984.

- The Fall of Paris, Simon Publications, 2002.

- My Paris, Editions 7, Paris, 2005

References

edit- ^ Medding, Peter Y. (1999). "Coping with Life and Death". Studies in Contemporary Jewry. Vol. XIV. Oxford University Press. p. 277. ISBN 0195351886.

- ^ Shrayer, Maxim D. (26 March 2015). An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature: Two Centuries of Dual Identity in Prose and Poetry. Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-317-47696-2.

- ^ Slezkine, Yuri (7 August 2017). The House of Government. Princeton University Press. pp. 26–27. doi:10.1515/9781400888177. ISBN 978-1-4008-8817-7.

- ^ Rhyne, George N.; Adams, Bruce Friend (1995). The Supplement to The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian, Soviet and Eurasian History: Dzhungar Khanate - Estates. Academic International Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-87569-142-8.

- ^ Cohen, Stephen F. (1980). Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888-1938. Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-502697-9.

- ^ Polonsky, Antony (9 February 2012). The Jews in Poland and Russia: Volume III: 1914 to 2008. Liverpool University Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-78962-782-4.

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Ilya Ehrenburg". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015.

- ^ Toscano, Alberto; Kinkle, Jeff (2015). Cartographies of the Absolute. Zero. pp. 192, 285.

- ^ Abdelhadi, Jason (22 March 2016). "Breton vs Ehrenburg: A Détournement on the Boulevard Montparnasse". Peculiar Mormyrid. peculiarmormyrid.com. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2012). The Spanish Civil War (50th Anniversary ed.). London: Penguin Books. p. 380. ISBN 978-0-141-01161-5.

- ^ Thomas (2012) p. 678.

- ^ a b c Rubenstein, Joshua. "Ehrenburg, Ilya Grigor'evich". YIVO Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ a b c David-Fox, Michael; Holquist, Peter; Martin, Alexander M. (2012). Fascination and Enmity: Russia and Germany as Entangled Histories, 1914–1945. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8229-7810-7.

- ^ a b Beevor, Antony (2007). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-103239-9.

Ilya Ehrenburg's own mesmerizing calls for revenge on Germany in his articles in the Red Army newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) had created a huge following among the frontoviki, or frontline troops. Goebbels responded with loathing against 'the Jew Ilya Ehrenburg, Stalin's favourite rabble-rouser'. The propaganda ministry accused Ehrenburg of inciting the rape of German women. Yet while Ehrenburg never shrank from the most bloodthirsty harangues, the most notorious statement, which is still attributed to him by western historians, was a Nazi invention. He is accused of having urged "Red Army soldiers to take German women as their 'lawful booty' and to 'break their racial pride'.

- ^ Dobbs, Michael (2012). Six Months in 1945: FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman--from World War to Cold War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-307-96089-4.

- ^ Orlando Figes The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, 2007, ISBN 0805074619, p. 414.

- ^ Suppan, Arnold (2019). Hitler–Beneš–Tito: National Conflicts, World Wars, Genocides, Expulsions, and Divided Remembrance in East-Central and Southeastern Europe, 1848–2018. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. p. 739. doi:10.2307/j.ctvvh867x. ISBN 978-3-7001-8410-2. JSTOR j.ctvvh867x. S2CID 214097654.

- ^ Miner, Steven Merritt (2003). Stalin's Holy War: Religion, Nationalism, and Alliance Politics, 1941-1945. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8078-6212-4.

- ^ Reinisch, Jessica (2013). The Perils of Peace: The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany. OUP Oxford. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-19-966079-7.

- ^ Gil, Isabel Capeloa; Martins, Adriana (2012). Plots of War: Modern Narratives of Conflict. Walter de Gruyter. p. 109. ISBN 978-3-11-028303-7.

- ^ Товарищ Эренбург упрощает. vivovoco.rsl.ru.

- ^ ПИСЬМО И.Г. ЭРЕНБУРГА И.В. СТАЛИНУ. vivovoco.rsl.ru

- ^ Rubenstein, Joshua: Tangled Loyalties. The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg. 1st Paperback Ed., University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa (Alabama/USA) 1999 (= Judaic Studies Series), ISBN 0-8173-0963-2.

- ^ Carola Tischler: Die Vereinfachungen des Genossen Ehrenburg. Eine Endkriegs- und eine Nachkriegskontroverse. In: Elke Scherstjanoi (Hrsg.): Rotarmisten schreiben aus Deutschland. Briefe von der Front (1945) und historische Analysen. Texte und Materialien zur Zeitgeschichte, Bd. 14. K.G. Saur, München 2004, S. 326–339, ISBN 3-598-11656-X, p. 336-.

- ^ "Answer to a Letter".

- ^ Blumenthal, Helaine (2009). "Communism on Trial: The Slansky Affair and Anti-Semitism in Post-WWII Europe" (PDF). escholarship.org. p. 18.

- ^ Clark, Katerina; Dobrenko, Evgeny (2007). Soviet Culture and Power, A History in Documents, 1917-1953. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-300-10646-6.

- ^ Rubenstein, Joshua; Naumov, Vladimir P. (2001). Stalin's Secret Pogrom, The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-300-08486-2.

- ^ "Foreign News: Towers in Babel". Time. 10 January 1955.

- ^ Orlando Figes The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, 2007, ISBN 0805074619, pp. 590–591.

- ^ Stacy, Robert H. (1974). Russian Literary Criticism: A Short History. Syracuse University Press. p. 222 [1]. ISBN 9780815601081.

- ^ Tatu, Michel (1969). Power in the Kremlin. London: Collins. pp. 301–02.

- ^ Shneiderman, S.L. Ilye Erenburg [Eng: Ilya Ehrenburg]. New York: Yidisher Kempfer, 1968.

- ^ Rubenstein, Joshua (1996). Tangled Loyalties: The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg. New York: Basic Books.

- ^ Estraikh, Gennady (2008). Yiddish in the Cold War. London: Legenda.

- ^ Books: Kosher Candida, a review of The Stormy Life of Lasik Roitschwantz.

- ^ Muchnic, Helen (11 March 1965). "Ilya Ehrenburg's Story". New York Review of Books. 4 (3). Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

Sources

edit- Clark, Katerina (2011). Moscow, the Fourth Rome. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06289-4.

- Gilburd, Eleonory (2018). To See Paris and Die: The Soviet Lives of Western Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98071-6.

- Goldberg, Anatol (1984). Ilya Ehrenburg: Writing, Politics and the Art of Survival. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Laychuk, Julian L. (1991). Ilya Ehrenburg. New York: Herbert Lang. ISBN 978-3-261-04292-7.

- Sicher, Efraim (1995). Jews in Russian Literature After the October Revolution: Writers and Artists Between Hope and Apostasy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521481090.

- Shneiderman, S.L. Ilye Erenburg [Eng: Ilya Ehrenburg]. New York: Yidisher Kempfer, 1968.

- Rubenstein, Joshua (1999). Tangled Loyalties: The Life and Times of Ilya Ehrenburg. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0963-3.

Further reading

edit- Moody, C., ed. (2014). Ilya Ehrenburg: Selections from People, Years, Life (in Russian). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-3619-6.

External links

edit- Media related to Ilya Ehrenburg at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by or about Ilya Ehrenburg at the Internet Archive

- Works by Ilya Ehrenburg at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- To Remember at Facing History and Ourselves