Idora Park (1899–1984) was an amusement park in Youngstown, Ohio, United States, also known as "Youngstown's Million Dollar Playground."

Idora Park | |

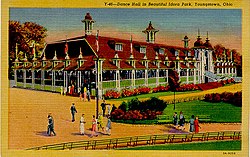

The Dance Hall at Idora Park, c. 1935 | |

| Location | Sw of the jct. of McFarland and Parkview Aves., Youngstown, Ohio |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°4′20″N 80°41′6″W / 41.07222°N 80.68500°W |

| Architect | Harton, T.M., Co.; Philadelphia Toboggan Co. |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival, Moderne, Italianate |

| NRHP reference No. | 93000895 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 13, 1993 |

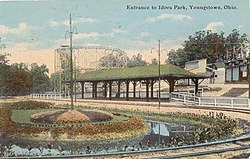

Built by the Youngstown Park and Falls Street Railway Company, the park's expansion coincided with the growth of the South Side of Youngstown, Ohio, in the Fosterville neighborhood. Prior to its closure in the wake of a devastating fire, Idora Park was one of the nation's few remaining urban amusement parks.

Opening and early development

editThe park opened as Terminal Park on May 30, 1899, which was Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day). At that time in America, it was common for amusement parks called trolley parks to sprout at the end of trolley lines to generate weekend revenue. Without an admission fee, anyone who could afford the trolley fare could enter the park. This trolley park's first season presented its guests a bandstand, theater, dance pavilion, a roller coaster, a circle swing, and concession stands. It was later renamed Idora Park.

When a bridge spanning the Mahoning River opened on Youngstown's Market Street on May 23, 1899, the entire South Side was unrolled for development. The trolley line linking the downtown to Idora Park ran south on Market, west on Warren, south on Hillman Street, Sherwood west to Glenwood Avenue, then cruised through Parkview Avenue (west) into the Idora terminal.

Major attractions

editRoller coasters

editOne of the park's many attractions was a wooden roller coaster with a length of 3,000 feet (910 m) and the height of 85 feet high, called the Wild Cat, which opened in 1930. The state-of-the-art, three-minute ride was hailed by roller coaster connoisseurs across the country. The Wild Cat was designed by Herbert Paul Schmeck, who held 100 patents for roller coaster innovations. In 1984, the Wild Cat was still ranked among the top ten roller coasters in the world.

Another notable feature at the park was the Jack Rabbit, a wooden roller coaster constructed in 1910 by TM Harden. Standing 70 feet (21 meters) tall and spanning 2,200 feet (670 meters) in length, it provided a ride lasting two minutes and thirty seconds. During the 1930s, the coaster underwent expansions and structural adjustments.In a bid to attract more visitors for the 1984 season, the park's owners decided to reverse the direction of the Jack Rabbit's trains and rebranded it as the Back Wabbit.

Kiddieland

editThe Kiddieland area was originally a giant concrete swimming pool. When the park was built, it included the pool and a large bath house. A large hole was drilled into the pool to connect to an underground saltwater spring, creating the only saltwater pool in the country.[2] To address the park's space concerns, the pool was replaced with a children's rides section during the 1950s. The bath house became a shelter and storage area.

The Kiddieland area included smaller and slower rides for children, some of which were touted as miniature versions of Idora Park's rides, such as the open-air children's version of the Idora Special train Archived September 18, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. A small wooden roller coaster was considered a children's version of one of the featured large-scale rollercoasters. Other attractions included an open air, roofed picnic table area (where attendees could serve food they brought from outside the park) and an old-fashioned automobile pathway which had a self-guiding track but allowed for a minor amount of steering so that even children could feel they were actually driving these low-powered gasoline vehicles. Children's midway games were also present.

Ballroom

editThe Idora Park Ballroom opened June 30, 1910. The open-air ballroom was based on one in Coney Island, New York. It was billed as the largest dance floor between New York City and Chicago.[3] The hardwood-floored ballroom eventually became enclosed to allow for year-round use.

Idora Park's house band played in the ballroom until the advent of radio in the 1930s. Radio increased the level of listener sophistication, and Idora Park soon began to hire to big-name bands. Subsequent decades brought glorious entertainment to the ballroom: dances, concerts, New Year's parties, and Presidential campaign visits from John F. Kennedy. High-profile musical acts that played the ballroom included: the Glenn Miller Orchestra, the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, the Eagles, Ray Charles, Maynard Ferguson, Blue Öyster Cult and The Monkees.[citation needed]

Other attractions

editAdditional attractions and features of Idora Park included Kooky Castle, a haunted house; Laffin Lena's, a funhouse (which featured a hall of mirrors); Old Saw Mill, a water boat ride; Tilt-O-Whirl; the Scrambler; the Caterpillar; the Orbit prior to the Scrambler; bumper-cars; a Ferris Wheel; a small passenger train (Idora Express) which traveled through the park; and a spinning ride (The Rockets) with three bus-sized stainless steel open-air rocket ships which were attached by thick cables. The base of the rocket ride were refreshments and cotton candy. Adjacent to the rocket ride was a french fry stand which was one of the most popular and famous items sold at Idora Park. Midway games, including a shooting gallery and a penny arcade, were present in several locations of the park along with a miniature golf course.

Decline

editIdora Park thrived through the decades, yet it also faced continual competition from larger state and national amusement parks. Landlocked on its 27 acres (110,000 m2), Idora had no options for expansion. As the automobile became the preferred mode of transportation, trolley lines died out, and so did many trolley parks. The primary reason Idora had survived was it had become the preferred location for ethnic, church, and company picnics.

Youngstown Sheet and Tube, one of the largest employers in the Mahoning Valley, announced the closure of one of its largest mills on September 19, 1977. The overnight loss of nearly 5,000 jobs greatly impacted the Youngstown region's economy and Idora Park directly.

During the hardship the community was suffering, Idora Park still boasted existing rides. The Idora Park Merry-Go-Round was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. In 1976, Idora Park was named one of the nation's 100 best amusement parks in Gary Kyriazi's book, Great American Amusement Parks.[4] By 1980, the Wild Cat and Jack Rabbit were recognized in publications as some of the best coasters in the country.[citation needed]

Nonetheless, by the early 1980s, the park was a relic that also housed relics: it now housed rides from other parks, such as Euclid Beach Park in Cleveland and West View Park outside of Pittsburgh, that met their end in the 1960s and '70s.[citation needed]

1984 fire

editA devastating fire on April 26, 1984 destroyed the Wild Cat roller coaster, the Lost River ride, eleven concession stands, and the park office. Employees scrambled to save park records, but only some of the most current files were pulled to safety, while older files and historical records were lost. Employees tried to extinguish the growing flames with hand extinguishers, but soon realized that the fire was out of control.

Twelve fire companies responded to the fire, which spread quickly as winds carried it across concession stands and on to the midway. Many off-duty firefighters also responded to the call to help contain flames that spread along the Wild Cat's wooden tracks and threatened the merry-go-round, which was scorched but ultimately saved from destruction.[5] Firefighters found themselves at a disadvantage with a lack of in-park hydrants, poor water pressure, and aged wooden rides and buildings. They finally tamed the blaze by running lines to hydrants outside the park.

Final damage was estimated in millions of dollars. Intense heat melted paint in various areas of the gazebo. The south horseshoe of the Wild Cat was destroyed, and the repair cost was prohibitive.

The park operated through the summer of 1984, but with the premier ride gone, a decision was made to close permanently. Idora Park welcomed its last visitors on September 16, 1984.

On October 20–21, 1984, an auction was conducted by Norton Auctioneers of Coldwater, Michigan to dispose of the rides and equipment. The remaining coasters (Wild Cat, Jack Rabbit, Baby Wild Cat), and many other buildings (Ballroom, Kiddieland complex, French Fry stand) were abandoned.

New ownership

editIn 1985, Mt. Calvary Pentecostal Church in Youngstown bought the Idora property and announced plans for a religious complex, to be named the "City of God". The Ballroom remained open for various events until Memorial Day 1986. The church lost access to the property in 1989 after accumulating more than $500,000 in debt on the land.

Deterioration

editIn an interview with the Youngstown Vindicator on October 16, 1984, former Idora Park owner Max Rindin was asked what would happen to the Park after it closed. “In time,” he said. “It’ll all be torched.” Gradually, his prophecy came true. Another fire at the abandoned park on May 3, 1986, destroyed the Heidelberg Gardens, Kooky Castle (haunted house), Laffin Lena's (fun house), and the Helter Skelter bumper car buildings. But until that fire, there was always a tangible reminder of Idora Park.

Over time, Mt. Calvary failed to build their religious complex, the property decayed, and it was not secured from trespassers. The former Idora Park's remaining structures were eventually vandalized, destroyed by natural elements, or succumbed to arson.

Calls for preservation

editBy 1999, Conneaut Lake Park Management Group (which had taken over Conneaut Lake Park in Conneaut Lake, Pennsylvania; about 65 mi (100 km) from Idora Park), attempted to negotiate the purchase of either the Jack Rabbit or Wild Cat from the property owners. Blueprints for both rides were still available, so they could be refurbished at Conneaut. The group also planned to purchase the complete merry-go-round from the owners in New York. These plans never materialized. The ballroom, Jack Rabbit, and Wild Cat remained unpreserved on the property.

2001 fire

editOn March 5, 2001, the final chapter to Idora Park's history was written when the Ballroom burned down. The fire reportedly started in the basement and was suspicious in nature. The Jack Rabbit and other remaining wooden structures were not destroyed by this fire. Days after the fire, an interview with the property owners stated that they "offered to allow (preservation groups) to take the roller coasters down as long as they funded it and had proper insurance and bonding".[6] However, on July 26, 2001, the Wild Cat, Jack Rabbit, and all other decaying structures (all unsalvageable) were demolished by bulldozers to prevent any future fires. City officials had asked that the coasters be removed since they were hazardous to the public. Both the Jack Rabbit and Wild Cat were listed on the American Coaster Enthusiasts (ACE) preservation list. Inaction by the park property owners to preserve these remaining Idora Park historic structures ultimately led to their destruction. In a 2001 news conference following the Ballroom's messy asbestos cleanup, Mt. Calvary Pentecostal Church restated that: "This future complex (City of God) will only help the entire community but especially youth... hopes to break ground no later than next spring (2002). The entire project should take at least two years to complete."[7] As of May 3, 2013, Mt. Calvary Pentecostal Church has yet to break ground on the "City of God" project.[8]

Future development possibilities

editAlthough the property still belongs to Mt. Calvary Pentecostal Church, the land is vacant of buildings, and City of God project was never realized. "The Mahoning County Common Pleas Court dismissed the delinquent tax case against the owners of the former Idora Park...."[9] The case was dismissed because one of the parties named in the suit, Teen Missions International, Inc. of Merritt Island, Florida, paid the delinquent taxes on behalf of Mt. Calvary Church. Teen Missions International helps churches and other religious organizations with financing different projects. Teen Missions has loaned nearly $1.2 million to Mount Calvary over a period of time to help develop the Idora property. Mt. Calvary Church subsequently filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy by February 2017, with the majority of the outstanding debt being related to the delinquent taxes on the Idora Park property.[10]

The Youngstown 2010 redevelopment and city revitalization plans have also stated their interest in acquiring the property to utilize it as a green space extension of nearby Mill Creek Park. These plans are on hold until the city can obtain the property from the Church (possibly through eminent domain), or alternative ownership acquires the property from the Church's outstanding $1.5 million lawsuit.

In April 2014, Jim and Toni Amey of nearby Canfield, Ohio, owners of many Idora Park artifacts, opened a museum next to their house called The Idora Park Experience, showcasing many of the artifacts.[11] The museum opens approximately twice a year, and also sells commemorative items related to the park. Following the Mt. Calvary Church's bankruptcy filing, the owners of the museum told the bankruptcy court that they planned on making a bid for the property, valued at $52,000.[12] Despite offering more money than the property was worth, Mt. Calvary Church refused to sell the property, though the couple hoped that bankruptcy court would force a sale by public auction.[13]

Better fate of the carousel

editReferences

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Samuelson, Dale; Yegoiants, Wendy (2001), The American Amusement Park, MBI Publishing Company, ISBN 9780760309810

- ^ "Beautiful Idora Ballroom Is Set For Big Opening". The Youngstown Daily Vindicator. May 19, 1933.

- ^ Kyriazi, Gary (1976), The Great American Amusement Parks: A Pictorial History, Citadel Press, ISBN 9780806505251

- ^ The Youngstown Fire Department prevented it from catching fire by continually pouring water on the roof of the octagonal building.

- ^ Linert, Brenda J.; Gorman, Joe (2001). "Idora Park's owners consider toppling roller coasters". Tribune Chronicle. republished at Google Groups. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "27 First News at 6". WKBN. May 30, 2001. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Youngstown church reveals new plans for old Idora Park property". WFMJ.com. Youngstown, Ohio: WFMJ. May 9, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ "Former Idora Park site taxes dismissed". Tribune Chronicle. Warren, Ohio. January 8, 2007.

- ^ "Church in Youngstown owing $1.6M files for bankruptcy". WKBN.com. Youngstown, Ohio: WKBN-TV. February 23, 2017.

- ^ "Idora Park Experience brings historical amusement park back to life". WKBN.com. Youngstown, Ohio: WKBN-TV. October 15, 2016.

- ^ "Idora Park museum owners want to buy original land in Youngstown". WKBN.com. Youngstown, Ohio: WKBN-TV. March 27, 2017.

- ^ "Bankrupt church refuses to sell old Idora Park land for museum". WKBN.com. Youngstown, Ohio: WKBN-TV. April 26, 2017.

Further reading

edit- Guerrieri, Vince. "Youngstown's Million Dollar Playground", The New Colonist, September 10, 2004.

- Shale, Rick. "Idora Park: Last Ride of the Summer", Amusement Park Journal, May 1999.

- Amey, James M. and Toni L. "Lost Idora Park", (Images of America), Arcadia, August 2019.

External links

edit- History of Idora Park

- Idora Park Photo Tour, Late 1990s Archived January 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- The Idora Park Experience