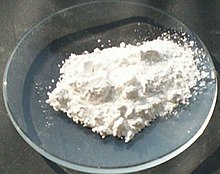

Calcium hydroxide (traditionally called slaked lime) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Ca(OH)2. It is a colorless crystal or white powder and is produced when quicklime (calcium oxide) is mixed with water. Annually, approximately 125 million tons of calcium hydroxide are produced worldwide.[8]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Calcium hydroxide

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.762 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E526 (acidity regulators, ...) |

| 846915 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Ca(OH)2 | |

| Molar mass | 74.093 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.211 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 580 °C (1,076 °F; 853 K) (loses water, decomposes) |

| |

Solubility product (Ksp)

|

5.02×10−6 [1] |

| Solubility |

|

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 12.63 pKa2 = 11.57[2][3] |

| −22.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.574 |

| Structure | |

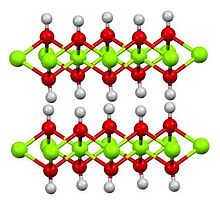

| Hexagonal, hP3[4] | |

| P3m1 No. 164 | |

a = 0.35853 nm, c = 0.4895 nm

| |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

83 J·mol−1·K−1[5] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−987 kJ·mol−1[5] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H314, H335, H402 | |

| P261, P280, P305+P351+P338 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

7340 mg/kg (oral, rat) 7300 mg/kg (mouse) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 15 mg/m3 (total) 5 mg/m3 (resp.)[7] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 5 mg/m3[7] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[7] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | [6] |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations

|

Magnesium hydroxide Strontium hydroxide Barium hydroxide |

Related bases

|

Calcium oxide |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Calcium hydroxide (data page) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Calcium hydroxide has many names including hydrated lime, caustic lime, builders' lime, slaked lime, cal, and pickling lime. Calcium hydroxide is used in many applications, including food preparation, where it has been identified as E number E526. Limewater, also called milk of lime, is the common name for a saturated solution of calcium hydroxide.

Solubility

editCalcium hydroxide is modestly soluble in water, as seen for many dihydroxides. Its solubility increases from 0.66 g/L at 100 °C to 1.89 g/L at 0 °C.[8] Its solubility product Ksp of 5.02×10−6 at 25 °C,[1] its dissociation in water is large enough that its solutions are basic according to the following dissolution reaction:

- Ca(OH)2 → Ca2+ + 2 OH−

The solubility is affected by the common-ion effect. Its solubility drastically decreases upon addition of hydroxide or calcium sources.

Reactions

editWhen heated to 512 °C, the partial pressure of water in equilibrium with calcium hydroxide reaches 101 kPa (normal atmospheric pressure), which decomposes calcium hydroxide into calcium oxide and water:[9]

- Ca(OH)2 → CaO + H2O

When carbon dioxide is passed through limewater, the solution takes on a milky appearance due to precipitation of insoluble calcium carbonate:

- Ca(OH)2(aq) + CO2(g) → CaCO3(s) + H2O(l)

If excess CO2 is added: the following reaction takes place:

- CaCO3(s) + H2O(l) + CO2(g) → Ca(HCO3)2(aq)

The milkiness disappears since calcium bicarbonate is water-soluble.

Calcium hydroxide reacts with aluminium. This reaction is the basis of aerated concrete.[8] It does not corrode iron and steel, owing to passivation of their surface.

Calcium hydroxide reacts with hydrochloric acid to give calcium hydroxychloride and then calcium chloride.

In a process called sulfation, sulphur dioxide reacts with limewater:

- Ca(OH)2(aq) + SO2(g) → CaSO3(s) + H2O(l)

Limewater is used in a process known as lime softening to reduce water hardness. It is also used as a neutralizing agent in municipal waste water treatment.

Structure and preparation

editCalcium hydroxide adopts a polymeric structure, as do all metal hydroxides. The structure is identical to that of Mg(OH)2 (brucite structure); i.e., the cadmium iodide motif. Strong hydrogen bonds exist between the layers.[10]

Calcium hydroxide is produced commercially by treating (slaking) quicklime with water:

- CaO + H2O → Ca(OH)2

Alongside the production of quicklime from limestone by calcination, this is one of the oldest known chemical reactions; evidence of prehistoric production dates back to at least 7000 BCE.[11]

Uses

editCalcium hydroxide is commonly used to prepare lime mortar.

One significant application of calcium hydroxide is as a flocculant, in water and sewage treatment. It forms a fluffy charged solid that aids in the removal of smaller particles from water, resulting in a clearer product. This application is enabled by the low cost and low toxicity of calcium hydroxide. It is also used in fresh-water treatment for raising the pH of the water so that pipes will not corrode where the base water is acidic, because it is self-regulating and does not raise the pH too much.[citation needed]

Another large application is in the paper industry, where it is an intermediate in the reaction in the production of sodium hydroxide. This conversion is part of the causticizing step in the Kraft process for making pulp. In the causticizing operation, burned lime is added to green liquor, which is a solution primarily of sodium carbonate and sodium sulfate produced by dissolving smelt, which is the molten form of these chemicals from the recovery furnace.[10]

In orchard crops, calcium hydroxide is used as a fungicide. Applications of 'lime water' prevent the development of cankers caused by the fungal pathogen Neonectria galligena. The trees are sprayed when they are dormant in winter to prevent toxic burns from the highly reactive calcium hydroxide. This use is authorised in the European Union and the United Kingdom under Basic Substance regulations.[12]

Calcium hydroxide is used in dentistry, primarily in the specialty of endodontics.

Food industry

editBecause of its low toxicity and the mildness of its basic properties, slaked lime is widely used in the food industry,

- In USDA certified food production in plants and livestock[13]

- To clarify raw juice from sugarcane or sugar beets in the sugar industry (see carbonatation)

- To process water for alcoholic beverages and soft drinks

- To increase the rate of Maillard reactions (pretzels)[14]

- Pickle cucumbers and other foods

- To make Chinese century eggs

- In maize preparation: removes the cellulose hull of maize kernels (see nixtamalization)

- To clear a brine of carbonates of calcium and magnesium in the manufacture of salt for food and pharmaceutical uses

- In fortifying (Ca supplement) fruit drinks, such as orange juice, and infant formula

- As a substitute for baking soda in making papadam

- In the removal of carbon dioxide from controlled atmosphere produce storage rooms

- In the preparation of mushroom growing substrates[15]

Native American uses

editIn Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the word for calcium hydroxide is nextli. In a process called nixtamalization, maize is cooked with nextli to become nixtamal, also known as hominy. Nixtamalization significantly increases the bioavailability of niacin (vitamin B3), and is also considered tastier and easier to digest. Nixtamal is often ground into a flour, known as masa, which is used to make tortillas and tamales.[citation needed]

Limewater is used in the preparation of maize for corn tortillas and other culinary purposes using a process known as nixtamalization. Nixtamalization makes the niacin nutritionally available and prevents pellagra.[16] Traditionally lime water was used in Taiwan and China to preserve persimmon and to remove astringency.[17]: 623

In chewing coca leaves, calcium hydroxide is usually chewed alongside to keep the alkaloid stimulants chemically available for absorption by the body. Similarly, Native Americans traditionally chewed tobacco leaves with calcium hydroxide derived from burnt mollusc shells to enhance the effects. It has also been used by some indigenous South American tribes as an ingredient in yopo, a psychedelic snuff prepared from the beans of some Anadenanthera species.[18]

Asian uses

editCalcium hydroxide is typically added to a bundle of areca nut and betel leaf called "paan" to keep the alkaloid stimulants chemically available to enter the bloodstream via sublingual absorption.

It is used in making naswar (also known as nass or niswar), a type of dipping tobacco made from fresh tobacco leaves, calcium hydroxide (chuna/choona or soon), and wood ash. It is consumed most in the Pathan diaspora, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. Villagers also use calcium hydroxide to paint their mud houses in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Hobby uses

editIn buon fresco painting, limewater is used as the colour solvent to apply on fresh plaster. Historically, it is known as the paint whitewash.

Limewater is widely used by marine aquarists as a primary supplement of calcium and alkalinity for reef aquariums. Corals of order Scleractinia build their endoskeletons from aragonite (a polymorph of calcium carbonate). When used for this purpose, limewater is usually referred to as Kalkwasser. It is also used in tanning and making parchment. The lime is used as a dehairing agent based on its alkaline properties.[19]

Personal care and adornment

editTreating one's hair with limewater causes it to stiffen and bleach, with the added benefit of killing any lice or mites living there. Diodorus Siculus described the Celts as follows: "Their aspect is terrifying... They are very tall in stature, with rippling muscles under clear white skin. Their hair is blond, but not only naturally so: they bleach it, to this day, artificially, washing it in lime and combing it back from their foreheads. They look like wood-demons, their hair thick and shaggy like a horse's mane. Some of them are clean-shaven, but others – especially those of high rank, shave their cheeks but leave a moustache that covers the whole mouth...".[20][21]

Calcium hydroxide is also applied in a leather process called liming.

Interstellar medium

editThe ion CaOH+ has been detected in the atmosphere of S-type stars.[22]

Limewater

editLimewater is a saturated aqueous solution of calcium hydroxide. Calcium hydroxide is sparsely soluble at room temperature in water (1.5 g/L at 25 °C[23]). "Pure" (i.e. less than or fully saturated) limewater is clear and colorless, with a slight earthy smell and an astringent/bitter taste. It is basic in nature with a pH of 12.4. Limewater is named after limestone, not the lime fruit. Limewater may be prepared by mixing calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) with water and removing excess undissolved solute (e.g. by filtration). When excess calcium hydroxide is added (or when environmental conditions are altered, e.g. when its temperature is raised sufficiently), there results a milky solution due to the homogeneous suspension of excess calcium hydroxide. This liquid has been known traditionally as milk of lime.

Health risks

editUnprotected exposure to Ca(OH)2, as with any strong base, can cause skin burns, but it is not acutely toxic.[8]

See also

edit- Baralyme (carbon dioxide absorbent)

- Cement

- Lime mortar

- Lime plaster

- Plaster

- Magnesium hydroxide (less alkaline due to a lower solubility product)

- Soda lime (carbon dioxide absorbent)

- Whitewash

- On Food and Cooking

References

edit- ^ a b John Rumble (18 June 2018). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (99 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 5–188. ISBN 978-1138561632.

- ^ "Sortierte Liste: pKb-Werte, nach Ordnungszahl sortiert. – Das Periodensystem online".

- ^ ChemBuddy dissociation constants pKa and pKb

- ^ Petch, H. E. (1961). "The hydrogen positions in portlandite, Ca(OH)2, as indicated by the electron distribution". Acta Crystallographica. 14 (9): 950–957. Bibcode:1961AcCry..14..950P. doi:10.1107/S0365110X61002771.

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A21. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ "MSDS Calcium hydroxide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0092". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c d Kenny, Martyn; Oates, Tony (2007). "Lime and Limestone". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_317.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- ^ Halstead, P. E.; Moore, A. E. (1957). "The Thermal Dissociation of Calcium Hydroxide". Journal of the Chemical Society. 769: 3873. doi:10.1039/JR9570003873.

- ^ a b Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ^ "History of limestone uses – timeline". Science Learning Hub – Pokapū Akoranga Pūtaiao. Curious Minds New Zealand. 1 October 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ European Union (13 May 2015). "COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2015/762 of 12 May 2015 approving the basic substance calcium hydroxide in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the placing of plant protection products on the market, and amending the Annex to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 540/2011". Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Pesticide Research Institute for the USDA National Organic Program (23 March 2015). "Hydrated Lime: Technical Evaluation Report" (PDF). Agriculture Marketing Services. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ Borsook, Alec (6 August 2015). "Cooking with Alkali". Nordic Food Lab.

- ^ "Preparation of Mushroom Growing Substrates". North American Mycological Association. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Wacher, Carmen (1 January 2003). "Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology to process maize at small-scale with great potential for improving the nutritional quality of maize based foods". Food Based Approaches for a Healthy Nutrition in Africa. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018.

- ^ Hu, Shiu-ying (2005). Food plants of China. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. ISBN 962-201-860-2. OCLC 58840243.

- ^ de Smet, Peter A. G. M. (1985). "A multidisciplinary overview of intoxicating snuff rituals in the Western Hemisphere". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 3 (1): 3–49. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(85)90060-1. PMID 3887041.

- ^ The Nature and Making of Parchment by Ronald Reed [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Diodorus Siculus, Library of History | Exploring Celtic Civilizations".

- ^ "Diodorus Siculus – Book V, Chapter 28". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Jørgensen, Uffe G. (1997), "Cool Star Models", in van Dishoeck, Ewine F. (ed.), Molecules in Astrophysics: Probes and Processes, International Astronomical Union Symposia. Molecules in Astrophysics: Probes and Processes, vol. 178, Springer Science & Business Media, p. 446, ISBN 079234538X.

- ^ 'Solubility of Inorganic and Metalorganic Compounds – A Compilation of Solubility Data from the Periodical Literature', A. Seidell, W. F. Linke, Van Nostrand (Publisher), 1953 [ISBN missing]

External links

edit- National Lime Association. "Properties of typical commercial lime products. Solubility of calcium hydroxide in water" (PDF). lime.org. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- National Organic Standards Board Technical Advisory Panel (4 April 2002). "NOSB TAP Review: Calcium Hydroxide" (PDF). Organic Materials Review Institute. Archived from the original (.PDF) on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Calcium Hydroxide

- MSDS Data Sheet