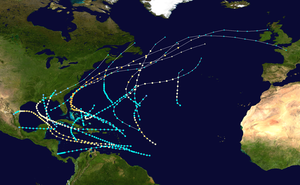

The 1887 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record at the time in terms of the number of known tropical storms that had formed, with 19. This total has since been equaled or surpassed multiple times. The 1887 season featured five off-season storms, with tropical activity occurring as early as May, and as late as December. Eleven of the season's storms attained hurricane status, while two of those became major hurricanes.[nb 1] It is also worthy of note that the volume of recorded activity was documented largely without the benefit of modern technology.[2] Consequently, tropical cyclones during this era that did not approach populated areas or shipping lanes, especially if they were relatively weak and of short duration, may have remained undetected. Thus, historical data on tropical cyclones from this period may not be comprehensive, with an undercount bias of zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 estimated.[3] The first system was initially observed on May 15 near Bermuda, while the final storm dissipated on December 12 over Costa Rica.

| 1887 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 15, 1887 |

| Last system dissipated | December 12, 1887 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Seven |

| • Maximum winds | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 952 mbar (hPa; 28.11 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 19 |

| Total storms | 19 |

| Hurricanes | 11 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 41+ total |

| Total damage | > $1.52 million (1887 USD) |

Of the known 1887 cyclones, the first and third were first documented in 1996 by José Fernández-Partagás and Henry F. Diaz. They also proposed large alterations to the known tracks of several of the other 1887 storms. Later, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project lengthened the tracks of the sixth and fifteen storms and upgraded the latter to a hurricane, although they did not add or remove any cyclones from the official hurricane database (HURDAT). In 2014, climate researcher Michael Chenoweth's reanalysis study recommended the removal of three storms and the addition of eight new systems to HURDAT, for a total of 24 cyclones in the 1887 season.

Only a few of the storms during the 1887 season did not impact land. The fourth system caused one death and more than $1.5 million (1887 USD) in damage,[nb 2] mostly due to flooding in the Southeastern United States. The next three hurricanes all passed offshore Newfoundland over a two-week period, together causing at least ten deaths. Next, the ninth system drowned 14 sailors and caused significant impacts over southern Texas and northeastern Mexico. Six tropical storm formed in October, among the most ever recorded during that month. At least $10,000 in damage occurred in Louisiana due to the thirteenth storm, while the sixteenth cyclone inflicted at least $7,000 in damage after sinking a ship and drowned two people after another vessel capsized. The season's nineteenth and final system resulted in 15 deaths across the Caribbean Sea.

Season summary

edit

The Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT) officially recognizes that 19 tropical cyclones formed during the 1887 season, 11 of which strengthened into a hurricane. Although both numbers set a record at the time, this activity has been surpassed or equaled many times, first in the 1933 season, which featured 20 tropical storms, while tying for the amount of hurricanes. Later, the 1969 season became the first to exceed the 1887 season's number of hurricanes, with 12. Currently, the seasonal records for most tropical storms is 30 and the most hurricanes is 15, set in 2020 and 2005, respectively.[1] Five storms existed outside the modern-day boundaries of an Atlantic hurricane season – June 1 to November 30 – which is also a record.[4]

The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project did not add or remove any storms from the 1996 reanalysis of the season by meteorologists José Fernández-Partagás and Henry F. Diaz, who both added the first and third systems. However, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project extended the tracks of the sixth and fifteenth systems and upgraded the fifteen storm to a hurricane.[5] A more recent reanalysis by climate researcher Michael Chenoweth, published in 2014, adds eight storms and removes three – the sixteenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth – for a net gain of five cyclones, although these proposed changes have yet to be approved for inclusion to HURDAT. If approved, the season would feature 24 tropical storms,[6] the third-most on record, behind only 2005 and 2020.[1] Chenoweth's study utilizes a more extensive collection of newspapers and ship logs, as well as late 19th century weather maps for the first time, in comparison to previous reanalysis projects.[6] Chenoweth's proposals have yet to be incorporated into HURDAT, however.[7]

Activity began early, with a pair of tropical storms in May, the first of which was detected by the Orinoco, docked at Bermuda, on May 15.[8] One system, another tropical storm, formed in June and caused some deaths and crop damage in Cuba, but only minor impacts along the Gulf Coast of the United States after striking Mississippi.[9] Tropical cyclogenesis then ceased until mid-July, when a storm was detected near Barbados.[7] The most significant effects of this system occurred in the Southeastern United States, where one death and about $1.5 million in agricultural damage alone occurred.[10][11] Another tropical storm developed in July. August featured both of the season's major hurricanes, which followed similar paths, first being observed just east of the Leeward Islands, striking or passing close to the Bahamas, recurving to the northeast just offshore the Southeastern United States, and then approaching Atlantic Canada just prior to becoming extratropical.[7] Both storms also caused multiple deaths.[12][13] The second of the two peaked with maximum sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) and an atmospheric pressure of 952 mbar (28.1 inHg), making it the most intense cyclone of the season.[5]

September had three cyclones, all of which became hurricanes.[7] The first of the three resulted in seven fatalities due to maritime incidents over the Grand Banks of Newfoundland,[13] while the second drowned fourteen sailors and caused significant impacts over southern Texas and northeastern Mexico.[14][15] Six tropical storms formed in October,[7] making it one of the most active Octobers on record.[16] The season's thirteenth storm caused at least $10,000 in damage after destroying a grain elevator in Louisiana,[17] while the sixteenth storm inflicted at least $7,000 in damage after sinking a ship and drowned two people after another vessel capsized.[12][17] Activity then went dormant until late November, when the track for the seventeenth system storm began north of Puerto Rico. In December, two tropical storms developed, with the second one dissipating on December 12 after striking Costa Rica.[7] Fifteen deaths occurred across the Caribbean Sea.[18] Because of these two storms and the seventeenth system lasting until at least early December, the season also featured the most active December on record.[19] Overall, the cyclones of the 1887 season collectively caused more than $1.52 million in damage and over 41 fatalities.[20]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 181, then the highest value ever recorded, but surpassed in 1893 and many other times since. ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have higher values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[1]

Systems

editTropical Storm One

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 15 – May 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); ≤997 mbar (hPa) |

On May 15, the steamship Orinoco, docked on Bermuda, reported gale-force winds and very heavy rainfall.[8] Consequently, the track for this storm begins to the south-southeast of the island on that day.[7] The Orinoco also recorded a barometric pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg) on May 16,[8] the day the storm made its closest approach to Bermuda, leading the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project to estimate that the cyclone peaked with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h).[5] Initially, the system moved northwestward, until turning to the north by May 17. It is likely that the storm became extratropical on the following day. The remnants then turned northeastward over Atlantic Canada, crossing Nova Scotia and Newfoundland before dissipating on May 20.[7] A reanalysis study authored by climate researcher Michael Chenoweth and published in 2014 considers this storm to have been a subtropical cyclone.[6]

Tropical Storm Two

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 17 – May 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); ≤1002 mbar (hPa) |

Based on data from the steamships Alvena, Athos, and Ponoma,[21] another May storm formed south of Jamaica on May 17 and initially moved generally northwestward. After passing just west of Jamaica on the following day, the cyclone then turned northeast.[7] The Alvena recorded a barometric pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.6 inHg) late on May 18,[22] causing the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project to estimate that the storm peaked with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[5] Early the next day, the cyclone made landfall in Cuba near Santa Cruz del Sur, several hours before emerging into the Atlantic. Throughout May 20, the storm crossed through the central Bahamas, passing near or over Exuma, Long Island, and Cat Island. The cyclone was last noted about halfway between Bermuda and the Bahamas on May 21.[7] Impact in Jamaica and Cuba as a result of this storm was mainly limited to some heavy rainfall and squally conditions.[22] Chenoweth proposed moving the path of the storm slightly farther west over Cuba and the Bahamas.[6]

Tropical Storm Three

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 11 – June 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); |

Weather conditions in Cuba beginning on June 11 suggest that a tropical depression over the northwestward Caribbean on June 11.[22][7] The depression passed just west of Cabo San Antonio early the following day while entering the Gulf of Mexico, where it quickly intensified into a tropical storm. However, it is estimated that the cyclone did not strengthen beyond winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) prior to making landfall near Pascagoula, Mississippi, early on June 14. The storm then dissipated later that day.[7] Chenoweth extends the duration of this cyclone back to June 10, with it attaining tropical storm status by the next day. The study by Chenoweth also concludes that this storm did not make landfall and instead meandered around the central Gulf of Mexico until dissipating on June 15.[6]

Heavy rains fell over western Cuba, leading to flooding. Meteorologist Simón Sarasola reported in 1928 that this flooding caused crop damage and a loss of "some lives". Offshore Pensacola, Florida, the steamship Vidette began taking on water, necessitating that the crew be rescued by a tugboat.[23]

Hurricane Four

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 20 – July 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 978 mbar (hPa) |

The bark Florence, stationed at Barbados on July 20, recorded squally weather and decreasing barometric pressures.[23] Consequently, the track for this system begins on that day about 150 mi (240 km) southeast of the island. Later on July 20, the cyclone entered the Caribbean after passing through Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Intensifying into a hurricane early the next day, the storm reached Category 2 status on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale on July 22. After moving west-northwestward for its duration thus far, the hurricane turned northwestward over the northwestern Caribbean on July 25. The cyclone struck the northeastern Yucatán Peninsula later that day and curved northward. Weakening to a Category 1 hurricane over the Gulf of Mexico, the storm turned north-northeastward. Around 15:00 UTC on July 27, the hurricane made landfall near Fort Walton Beach, Florida, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h), with an estimated barometric pressure of 978 mbar (28.9 inHg). The storm continued north-northeastward as a tropical storm, before dissipating late on July 28 near Atlanta, Georgia.[7] [23]

On Barbados, the storm caused several vessels to be wrecked or to be run aground. Although the hurricane passed far to the south of Cuba, it caused several vessels to sink at Batabanó and brought heavy rain and flooding to the islands interior.[24] In Florida, rainfall reached 8 in (200 mm) at Cedar Key.[25] Strong winds downed hundreds of trees and destroyed a college building, a mill, and several small homes in DeFuniak Springs. Damage in the town was estimated at $5,000. In Caryville, the storm partially destroyed a mill and demolished a church. Additionally, Holmes and Walton counties reported heavy agricultural damage.[26] Heavy rains fell in some other areas of the Southeastern United States, including a peak total of 16.5 in (420 mm) of precipitation at Union Point, Georgia.[27] According to The Atlanta Constitution, the Chattahoochee River overflowed its banks from Columbus, Georgia, to Apalachicola, Florida, submerging an average of 5 mi (8.0 km) of land along the waterway. [10] Consequently, extensive losses to cotton crops occurred, especially in Georgia and Alabama,[28] with agricultural damage alone estimated at $1.5 million.[10] One person drowned due to flooding in Georgia.[11]

The 2014 reanalysis study by Chenoweth suggested slower intensification, with the storm not reaching hurricane status until July 24. However, it became more intense, briefly becoming a Category 3 hurricane prior to landfall in the Florida Panhandle. Chenoweth also concluded that the cyclone moved slower inland and dissipated over southeast Georgia on July 29.[6]

Tropical Storm Five

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 30 – August 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

Although no observations related to this storm have been found prior to August 5,[29] HURDAT begins its track well east of the Windward Islands on July 30. Moving northwestward, the cyclone passed over or near Saint Vincent and the Grenadines on August 2 while entering the Caribbean. As the storm was located south of the Dominican Republic on August 5,[7] the bark Florence, stationed at the Turks and Caicos Islands, recorded winds of 58 mph (93 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg).[30] Early the next day, the cyclone brushed Haiti's Tiburon Peninsula and then continued northwestward. The system dissipated near the western tip of Cuba on August 8.[7]

Chenoweth proposes significant changes to the storm's track and duration, with the cyclone instead beginning as a tropical depression just east of the Leeward Islands on August 3. The storm remained just north of the Lesser and Greater Antilles until dissipating on August 7 over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.[6]

Hurricane Six

edit| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 14 – August 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); ≤967 mbar (hPa) |

On August 14, HURDAT begins the track for this system just east of the Leeward Islands,[7] the same day that Saint Kitts reported squalls and falling barometric pressures.[5] Moving northwestward and then west-northwestward, the cyclone intensified into a hurricane by August 17. On the following day, the system passed within 40 mi (65 km) of the Abaco Islands, likely as a Category 2 hurricane. The hurricane then began curving northeastward on August 19 and intensified into a Category 3 hurricane. Sustained winds likely increased slightly to 120 mph (195 km/h) as the storm passed just offshore North Carolina on August 20,[7] based on the steamship City of San Antonio recording a barometric pressure of 967 mbar (28.6 inHg).[5][31] The hurricane continued out to sea and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on August 22 about 250 mi (400 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[7]

In the Bahamas, The Nassau Guardian reported "A strong westerly breeze on Thursday last, accompanied by rain in the evening".[32] A schooner known as the Mabel F. Staples suffered severe damage near San Salvador Island.[33] With the storm passing just offshore North Carolina, the hurricane produced a 5-minute sustained windspeed of 82 mph (132 km/h) in Hatteras. Numerous vessels capsized in Pamlico Sound, while many homes along the shore were destroyed. Damage to telegraph lines in coastal North Carolina led to little to no communications from the Outer Banks for several days.[34] Offshore, the steamer Propitious encountered the hurricane approximately 60 mi (95 km) south of Cape Henry, Virginia. Rough seas swept away the captain.[12] Another person drowned over the Grand Banks of Newfoundland on August 22 after falling off the steamer Adriatic.[13]

Chenoweth adds a tropical depression stage on August 14. His 2014 study also proposes that extratropical transition occurred several hours later than HURDAT suggests.[6]

Hurricane Seven

edit| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 18 – August 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 952 mbar (hPa) |

Based on observations from Saint Kitts,[5] the track for this storm begins just east of the Leeward Islands on August 18. Following a similar trajectory to the previous system, this storm moved generally northwestward and intensified into a hurricane early on August 21. The cyclone the decelerated and strengthened into a Category 3 hurricane by August 22, when it struck the Abaco Islands near Marsh Harbour. Two days later, the system turned northward and then recurved northeastward on August 24.[7] Pressure observations from ships suggest that the hurricane peaked with sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h). On August 26, one day after the storm passed offshore North Carolina,[7] the steamship Peconia recorded a barometric pressure of 952 mbar (28.1 inHg), the lowest in relation to the cyclone.[5][35] The system passed near Newfoundland before becoming extratropical on August 27.[7]

In the Bahamas, the hurricane capsized or stranded 25-30 vessels at or close to Elbow Cay. Across the island, significant damage occurred to crops, fences, and structures, while the lighthouse also suffered some damage. Nassau reported only minimal impacts.[36] The cyclone produced sustained tropical storm-force winds over eastern North Carolina.[37] However, impacts in this region are unknown, possibly due to the previous storm downing telegraph wires.[34] Along the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, a person tied to the wreckage of the vessel Ocean Pride died, while the captain of the schooner Mabel Kenniston reported an additional unspecified number of bodies onboard.[13]

The 2014 reanalysis study by Chenoweth concludes that this storm formed before the previous, with the track beginning on August 14. This cyclone moved generally west-northwestward across the Atlantic and attained hurricane status by the next day. After reaching the Bahamas on August 22, the storm then follows a similar path to that listed in HURDAT.[6]

Hurricane Eight

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 963 mbar (hPa) |

A ship known as Inflexible first encountered this storm over the central Atlantic to the east-southeast of Bermuda on September 1.[38] Moved northwestward, the cyclone became a hurricane on the following day. Turning northeastward,[7] the storm likely intensified further, based on several ship reports, including the steamship Taormina recording a barometric pressure of 963 mbar (28.4 inHg).[39] The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project thus estimated that the cyclone became a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h),[5] while Fernández-Partagás and Diaz suggested that it may have strengthened into a major hurricane.[39] On September 4, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about halfway between Greenland and the Azores. Thereafter, the extratropical storm persisted until September 6, when it dissipated off the coast of Ireland.[7]

The Boston Globe noted that over the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, "Very few vessels of the thousand sail on the banks ... escaped loss to a greater or less extent". Among several maritime incidents, six crew members of the schooner Nellie Woodbury drowned, while a seventh person died on the schooner Atlantic after falling from the crosstrees to the deck.[13]

Chenoweth traced this storm back to August 28, when it was located west-southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. The cyclone moved generally northwestward until September 2, at which time the storm curved north-northeastward while just east of Bermuda. Rapidly accelerating, the system became extratropical west of Ireland late on September 4.[6]

Hurricane Nine

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 11 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

The official path for this storm begins just east of the Lesser Antilles on September 11,[7] based on the Monthly Weather Review low-pressure areas track map.[40] On the following day, the system passed between Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent as a strong tropical storm. Moving west-northwestward across the Caribbean for the next few days, the cyclone intensified into a hurricane on September 13. Around September 16, the storm began moving northwestward, one day before striking extreme northeast Yucatán Peninsula as a Category 2 with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). The cyclone likely weakened to a Category 1 hurricane but re-strengthened to a Category 2 over the south-central Gulf of Mexico on September 18. Turning westward on September 20, the hurricane again weakened to a Category 1 by the next day. Around 17:00 UTC on September 21, the storm made landfall near Brownsville, Texas, with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h).[7] The Point Isabel Lighthouse recorded a barometric pressure of 973 mbar (28.7 inHg).[41] Tracking inland, the cyclone decelerated and weakened as it crossed into northeastern Mexico, dissipating over Nuevo León late on September 22.[7]

Chenoweth's 2014 study begins this system over the western Caribbean on September 15. The storm moved northwestward and then followed a similar path to that listed in HURDAT, although it may have remained offshore the Yucatán Peninsula.[6]

Few land or maritime observations of the storm exist along its path across the Caribbean. Heavy rains in Louisiana flooded parts of the state, with The New York Times reporting "half of the parish of Plaquemines and all of the rear of St. Bernard are under water."[42] In Texas, Galveston reported sustained winds up to 50 mph (80 km/h) and coastal flooding, but mainly in low-lying areas. Closer to the hurricane's landfall location, Brownsville recorded sustained winds of 78 mph (126 km/h) and heavy rainfall, with 8 in (200 mm) of precipitation on September 21 and an additional 2.26 in (57 mm) on September 22.[43] Thirty-six hours of rainfall flooded low-lying areas and fourteen sailors were lost at sea.[14] Additionally, a number of buildings in Brownsville suffered destruction.[15] In northeastern Mexico, Matamoros was impacted particularly hard. Intense winds reportedly blew away all metal roofs and fences, while numerous frame homes suffered some degree of damage. Storm surge from the Rio Grande flooded the city's major streets with up to 3 ft (0.91 m) of water.[40] Heavy rains in Nuevo León caused the Morales and Salinas rivers to overflow. The ensuing floods damaged many homes and inundated fields across the northern and eastern portions of the state, leading to significant losses of sugarcane, corn, and other seed crops. Additionally, the flood substantially damaged a railway bridge owned by Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México.[15]

Hurricane Ten

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 983 mbar (hPa) |

HURDAT initiates the track for this system over the central Atlantic to the northeast of the Leeward Islands late on September 14,[7] slightly earlier than indicated by the Monthly Weather Review and the 1996 reanalysis by Fernández-Partagás and Diaz.[41] The storm initially moved north-northwestward until turning north-northeastward on September 16, shortly before it intensified into a hurricane. As the cyclone passed just east of Newfoundland later on September 18,[7] the steamship Marsala observed a barometric pressure of 983 mbar (29.0 inHg).[41] Thus, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project estimated that this storm peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[5] However, the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone several hours later.[7]

In Newfoundland, an observer at St. John's reported heavy rains and gale-like conditions. Several maritime incidents occurred, including many vessels beached at Placentia and Portugal Cove, while "Bonavista presents a dreadful scene", according to The New York Times.[41]

Chenoweth traces this storm back to September 12, when it was located about halfway between the Lesser Antilles and the Cabo Verde Islands. The storm attains hurricane status on September 14 and moves northwestward through the following day, by which time the it starts tracking northeastward. Consequently, the cyclone remained much farther east of Newfoundland.[6]

Tropical Storm Eleven

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 6 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

Based on information from the Monthly Weather Review, a tropical storm was first noted over the northwestern Caribbean on October 6.[44] Moving nearly due west, the system made landfall in Mexico near Punta Allen, Quintana Roo, with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) early the next day. After weakening slightly, the storm emerged into the Bay of Campeche late on October 7 and soon re-strengthened back to sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). Late on October 8, the cyclone struck Mexico again near Nautla, Veracruz, before rapidly dissipated by early on October 9.[7] The 2014 study by Chenoweth proposes a much more southerly track, with the storm instead striking Belize or Guatemala as a minimal hurricane before dissipating over the latter on October 9.[6]

Tropical Storm Twelve

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 8 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); ≤994 mbar (hPa) |

The steamship Alvena first encountered this storm on October 8, with the track beginning near Inagua in the Bahamas.[44] Because the Alvena recorded a barometric pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg), the storm is estimated to have peaked with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h).[44][5] Moving north-northwestward, the cyclone passed over the eastern Bahamas before being last noted early on October 9 to the east of the Abaco Islands.[7] Chenoweth reanalysis study concluded instead that the storm moved across Hispaniola and Cuba from October 7 to October 9, when it dissipated over the latter.[6]

Hurricane Thirteen

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 9 – October 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 978 mbar (hPa) |

The track for this system begins about 165 mi (265 km) northeast of Barbuda on October 9,[7] one day before the corvette Nalon encountered rough seas, wind shifts, and decreasing atmospheric pressures between Cuba and Haiti.[45] A tropical storm, the cyclone moved westward and made landfall in the Dominican Republic near Nagua early on October 11. The storm crossed Hispaniola and emerged into the Caribbean several hours later near Gonaïves, Haiti. Passing just south of southeastern Cuba, the system likely intensified into a hurricane on October 12. The cyclone then turned west-northwestward and remained offshore Cuba until October 14, when it made landfall on the south coast of Pinar del Río Province. Entering the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane curved north-northwestward on October 17 and then northeastward on the next day. Early on October 19, the cyclone made landfall near Grand Isle, Louisiana,[7] with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) and an estimated barometric pressure of 978 mbar (28.9 inHg).[5] Quickly weakening to a tropical storm, the cyclone briefly re-emerged into the Gulf of Mexico before striking Mississippi. Early on October 20, the system weakened to a tropical depression over Georgia, several hours before becoming extratropical over North Carolina.[7]

Chenoweth's study proposed that this cyclone instead originated near Jamaica and rapidly intensified into a major hurricane before making landfall in Mexico near Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo. The storm then moved generally northward over the Gulf of Mexico before mostly following the official track.[6]

Heavy rains fell in Cuba. Consequently, Sarasola noted in 1928 that the storm caused "great flooding", especially in El Roque and Vuelta Abajo.[45] In Belize (then known as British Honduras), the hurricane caused crop damage, particularly to bananas, across the southern areas of the colony. Intense winds also downed many trees, causing travel to become impossible in some places.[5] In Louisiana, considerable damage and some flooding occurred in New Orleans, which experienced its heaviest rainfall event in years, while many trees were downed in Algiers neighborhood.[46] A floating grain elevator was destroyed, with damage totaling about $10,000.[17] Outside New Orleans, the hurricane caused significant damage to cotton and sugarcane in Abbeville and Iberville Parish, respectively.[46] Additionally, between New Orleans and Morgan City, many plantations reported the destruction of many sugarcane crops.[47] In Pensacola, Florida, sustained winds reached 48 mph (77 km/h), downing many telegraph wires. Farther north, rough seas beached several vessels in the Northeastern United States.[17]

Hurricane Fourteen

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 10 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); ≤989 mbar (hPa) |

The track for this storm begins on October 10 over the central Atlantic, far from any landmasses.[7] However, on the following day, the steamers Aldanach and Ocean Prince encountered the storm, with the former reporting hurricane-force winds and a barometric pressure of 989 mbar (29.2 inHg).[48] Consequently, the maximum sustained winds attained by this system is estimated to be 85 mph (140 km/h).[5] By the following day, however, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone to the west of the Azores.[7] Chenoweth proposes a much earlier origin of this storm, on October 2 as a tropical storm well west-southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. The storm initially moves westward across the Atlantic before presumably assuming a more northwestward motion.[6]

Hurricane Fifteen

edit| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 15 – October 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); ≤975 mbar (hPa) |

The RMS Moselle reported hurricane-force winds and barometric pressures as low as 975 mbar (28.8 inHg) well east of the Lesser Antilles on October 16,[5] one day after the track for this storm begins.[7] Consequently, it is estimated that this cyclone attained Category 2 intensity and peaked with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) on October 16.[5] Moving northwestward, the system likely weakened to a tropical storm on October 18 and then turned northeastward. Late the next day, the cyclone weakened to a tropical depression and promptly dissipated.[7] Chenoweth initiates the track for this storm as a tropical depression on October 12 and also proposed adding an extratropical transition on October 20.[6]

Tropical Storm Sixteen

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 29 – October 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 993 mbar (hPa) |

The track for this cyclone begins on October 29 over the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Around 01:00 UTC the next day, the storm made landfall near Tarpon Springs, Florida, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). Later on October 30, the system emerged into the Atlantic near Daytona and soon began to strengthen.[7] The steamship Edith Godden recorded a barometric pressure of 993 mbar (29.3 inHg) on October 31.[49] Consequently, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project estimated that the system peaked with sustained winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) while situated just offshore North Carolina.[5] However, by late on October 31, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, which strengthened to hurricane-equivalent intensity as it passed about halfway between Bermuda and New England. The extratropical storm then traversed the Atlantic, striking southwestern England before dissipating over northwestern France on November 6.[7] In his 2014 study, Chenoweth argues that this storm was never tropical and that the strong winds occurred due to a pressure gradient.[6]

In its formative stages, the storm was responsible for causing rain from the Rio Grande Valley along the Gulf Coast to Florida.[17] In Florida, Fort Meade recorded light rainfall and falling barometric pressures.[5] Strong winds impacted coastal North Carolina, reaching up to 70 mph (110 km/h) at Kitty Hawk. Consequently, many telegraph poles fell throughout the Outer Banks.[34] Farther inland, Lenoir and Raleigh recorded heavy rains, reaching 4.18 in (106 mm), as well as some snow.[17] Strong winds also impacted coastal Virginia, with a 5-minute sustained wind speed of 78 mph (126 km/h) at Cape Henry.[12] Communications between Cape Henry and Norfolk were lost.[17] At least four ships sank. The crews of three ships were rescued; however, when the Manantico, two people died.[17][12][50][51] The Carrie Holmes alone led to a $7,000 loss upon being beached during the storm.[12] Farther north, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, reported sustained winds of 52 mph (84 km/h).[49]

Hurricane Seventeen

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 27 – December 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

HURDAT initiates the track for this storm on November 26,[7] one day before being encountered by the steamship Claribel near Fortune Island in the Bahamas.[52] The storm executed a small cyclonic loop just north of the eastern Bahamas early in its duration and strengthened into a hurricane early on November 29. However, while moving northeastward and away from the Bahamas on December 1, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm. Three days later, the system was last noted well east-northeast of Bermuda.[7] The 2014 reanalysis by Chenoweth traces this storm back to a tropical depression over the southwestern Caribbean on November 21. For several days, the system moved slowly and erratically around the central Caribbean until crossing Haiti between November 27 and November 28. Rather than execute a cyclonic loop, the cyclone then moves generally northeastward until becoming extratropical on December 2, although the remnants persisted until dissipating about halfway between the Azores and Greenland on December 11.[6]

Hurricane Eighteen

edit| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 4 – December 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

The track for this storm begins on December 4 to the east of the northernmost Lesser Antilles, based on weather conditions in Cuba.[53] Initially moving west-northwestward, the storm turned northeastward on December 6.[7] By the following day, several ships encountered the cyclone, including the Kate Fawcett, which recorded sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), indicating that the storm became a hurricane.[5] The system curved east-northeastward early on December 8, several hours before it became extratropical west of the Azores.[7] Chenoweth's reanalysis study proposes the removal of this storm from HURDAT on the grounds of "Insufficient supporting evidence from other neighboring data sources".[6]

Heavy gales impacted Cuba, particularly at Baracoa. There, large waves swept away almost 300 huts and homes. However, The New York Times attributed the wave action to a norther that had been impacting the area since the beginning of December.[53]

Tropical Storm Nineteen

edit| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 7 – December 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

Weather conditions over the Caribbean and observations from a steamer suggest that the presence of a tropical storm just east-southeast of Barbados on December 7.[53] Shortly after, the storm passed south of the island and then moved near or over Saint Vincent and the Grenadines later that day. Around December 9, the cyclone peaked with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). The storm curved west-southwestward and moved in that direction for the rest of its duration, brushing the Guajira Peninsula early the next day and then making landfall near Tortuguero, Costa Rica, late on December 12. Thereafter, the cyclone quickly weakened to a tropical depression and then dissipated.[7]

At the time, the cyclone was the only tropical storm to pass over Costa Rica on record. In 2016, Hurricane Otto passed over Costa Rica as a minimal hurricane. However, prior to doing this Otto made landfall in extreme southern Nicaragua.[54] Six years later, Tropical Storm Bonnie struck just north of the Costa Rica-Nicaragua border.[55] According to Chenoweth, this system may not have existed, noting "No evidence in logbooks in Lesser Antilles or newspaper accounts; cold air surge into Panama".[6] The storm wrecked approximately 70 vessels across the Caribbean, causing 15 deaths due to drowning, though the Monthly Weather Review described the weather conditions as a "norther".[18]

Other storms

editWhile HURDAT currently recognizes 19 tropical cyclones for the 1887 season,[7] Chenoweth proposed a total of 24 systems in his reanalysis study, published in 2014. This included the removal of three systems and the addition of eight storms others not listed in HURDAT.[6] If confirmed, the season would be the third-most active on record, behind only 2005 and 2020.[1]

The first unofficial system proposed by Chenoweth developed in the northwestern Caribbean on August 2. Moving just north of due west, the tropical storm struck northern British Honduras before dissipating on August 4. Another unofficial cyclone formed on August 31 over the Straits of Florida. The tropical storm moved slowly and eratically, striking near present-day Everglades City, Florida, on September 4, and then dissipating shortly thereafter. As this storm meandered over the Straits of Florida, Chenoweth proposed another system well west of the Cabo Verde Islands on September 2. Moving in a parabolic path, the cyclone remained far from land and peaked as a Category 2 hurricane before Chenoweth ends the track east-southeast of Newfoundland one week later. Chenoweth also proposed that two storms developed on September 30. The first trekked generally northeastward and peaked as a Category 1 hurricane before becoming extratropical northwest of the Azores on October 2. The second such system crossed through the Cape Verde Islands, and on October 9, was last noted northwest of the archipelago.[6]

Chenoweth's next proposed new storm originated over the southwestern Caribbean on November 2. Tracking generally northwestward, the system made landfall in Nicaragua near Prinzapolka as a Category 1 hurricane early on November 4 and quickly dissipated. On November 9, Chenoweth concluded that a subtropical storm formed southwest of the Azores. The system passed near Santa Maria Island before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone late on November 11. Chenoweth's final proposed cyclone, also a subtropical storm, developed well west-northwest of the Cabo Verde Islands on November 29. The storm remained far away from any landmasses and on December 1, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone.[6]

Season effects

editThis is a table of all of the known storms that have formed in the 1887 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, landfall, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1887 USD.

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 15–18 | Tropical storm | 70 (95) | ≤997 | Bermuda | Unknown | None | |||

| Two | May 17–21 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | ≤1002 | Cuba, Bahamas | Unknown | None | |||

| Three | June 11–14 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | Unknown | Gulf Coast of the United States (Mississippi) | Unknown | Unknown | |||

| Four | July 20–28 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 978 | Windward Islands, Mexico (Quintana Roo), Southeastern United States (Florida) | >$1.5 million | 1 | [26][10][11] | ||

| Five | July 30 – August 8 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1001 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles | Unknown | None | |||

| Six | August 14–22 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | ≤967 | Bahamas, North Carolina, Virginia, Grand Banks of Newfoundland | Unknown | 2 | [12][13] | ||

| Seven | August 18–27 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 952 | Bahamas, North Carolina, Virginia, Grand Banks of Newfoundland | Unknown | >1 | [13] | ||

| Eight | September 1–4 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 963 | Grand Banks of Newfoundland | Unknown | 7 | [13] | ||

| Nine | September 11–22 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 973 | Windward Islands, Mexico (Quintana Roo), Louisiana, Texas | Unknown | 14 | [14] | ||

| Ten | September 14–18 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 983 | Newfoundland | Unknown | None | |||

| Eleven | October 6–9 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | Unknown | Mexico (Quintana Roo) | Unknown | None | |||

| Twelve | October 8–9 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | ≤994 | Bahamas | Unknown | None | |||

| Thirteen | October 9–20 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 981 | Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles (Dominican Republic and Cuba), Gulf Coast of the United States (Louisiana), Southeastern United States | >$10,000 | None | [17] | ||

| Fourteen | October 10–12 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | ≤989 | None | None | None | |||

| Fifteen | October 15–19 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | ≤975 | None | None | None | |||

| Sixteen | October 29–31 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 993 | Gulf Coast of the United States (Florida), East Coast of the United States | >$7,000 | 2 | [12] | ||

| Seventeen | November 27 – December 4 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | Unknown | Bahamas | Unknown | None | |||

| Eighteen | December 4–8 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | Unknown | Cuba | Unknown | None | |||

| Nineteen | December 6–12 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | Unknown | Lesser Antilles, ABC islands, Colombia, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Costa Rica | Unknown | 15 | [18] | ||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 19 systems | May 15 – December 12 | 125 (205) | 952 | >$1.52 million | >41 | |||||

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- ^ All damage figures are in 1887 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

edit- ^ a b c d e North Atlantic Hurricane Basin (1851-2023) Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 2024. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ Mudd, Brian (May 31, 2020). "Rewind: What 1887 & 2012 have in common with 2020's hurricane season". WJNO. West Palm Beach, Florida. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Landsea, Christopher W. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In Murname, Richard J.; Liu, Kam-biu (eds.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- ^ Pandajis, Tim (April 29, 2022). "These are the tropical systems that formed outside of hurricane season". KHOU. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Landsea, Chrstopher W.; et al. (May 2015). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Chenoweth, Michael (December 2014). "A New Compilation of North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1851–98". Journal of Climate. 27 (12). American Meteorological Society: 8674–8685. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.8674C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00771.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved November 22, 2024. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c Fernández-Partagás, p. 8

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 9-10

- ^ a b c d "All Over The State". The Atlanta Constitution. July 30, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved August 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Drowned By the Rain". The Atlanta Constitution. July 30, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved August 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Roth, David M.; Cobb, Hugh (July 16, 2001). "Late Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". Virginia Hurricane History. Weather Prediction Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Fishermen's Woe". The Boston Globe. September 10, 1887. p. 5. Retrieved August 16, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Roth, David M. (February 4, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Camp Springs, Maryland. p. 27. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c Escobar Ohmstede, Antonio (August 1, 2004). Desastres agrícolas en México: catálogo histórico (Volumen 2) (in Spanish). Centro de Investigación y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social. p. 172. ISBN 9681671880. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Beven II, John L.; Stewart, Stacy R.; Pasch, Richard J.; Franklin, James L.; Knabb, Richard D.; Avila, Lixion A. (November 1, 2005). Monthly Tropical Weather Summary (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Atmospheric Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 15 (10). United States Signal Service: 273. October 1887. Bibcode:1887MWRv...15R.265.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1887)15[265b:APEIIA]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c Fernández-Partagás, p. 41

- ^ Tropical Cyclones – December 2023 (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. January 2024. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ View expanded list of sources

- * "The Storm". The Weekly Floridian. Tallahassee, Florida. p. 2. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- "All Over The State". The Atlanta Constitution. July 30, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved August 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Drowned By the Rain". The Atlanta Constitution. July 30, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved August 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roth, David M.; Cobb, Hugh (July 16, 2001). "Late Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". Virginia Hurricane History. Weather Prediction Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- "Fishermen's Woe". The Boston Globe. September 10, 1887. p. 5. Retrieved August 16, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- Roth, David M. (February 4, 2010). Texas Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Camp Springs, Maryland. p. 27. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- "Atmospheric Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 15 (10). United States Signal Service: 273. October 1887. Bibcode:1887MWRv...15R.265.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1887)15[265b:APEIIA]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- Fernández-Partagás, José; Diaz, Henry F. (1996). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources: Year 1887 (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- * "The Storm". The Weekly Floridian. Tallahassee, Florida. p. 2. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 8-9

- ^ a b c Fernández-Partagás, p. 9

- ^ a b c Fernández-Partagás, p. 10

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 10-11

- ^ "Atmospheric Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 15 (7). United States Signal Service: 185. July 1887. Bibcode:1887MWRv...15R.183.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1887)15[183b:APEIIA]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Storm". The Weekly Floridian. Tallahassee, Florida. p. 2. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 3-1.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 11-12

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 12

- ^ 1887 Storm 5 (.XLS). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 13

- ^ "A strong westerly breeze". The Nassau Guardian. August 20, 1887. p. 2. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ "Driven Into Nassau in Distress". The New York Times. August 30, 1887. p. 5. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c Hudgins, James E. (2000). "Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586 – An Historical Perspective". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 19

- ^ "Great Storm on the Bahamas". The Buffalo Express. September 19, 1887. p. 1. Retrieved August 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Sefcovic, Zachary P.; Sherman, Spencer (2023). "Tropical Cyclone Climatology 1851-2020". National Weather Service Newport/Morehead City, North Carolina. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 22

- ^ a b Fernández-Partagás, p. 23

- ^ a b Fernández-Partagás, p. 25

- ^ a b c d Fernández-Partagás, p. 29

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 24

- ^ 1887 Storm 9 (.XLS). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ a b c Fernández-Partagás, p. 30

- ^ a b Fernández-Partagás, p. 32

- ^ a b Roth, David M. (January 13, 2010). Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). National Weather Service, Southern Region Headquarters. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ "Storm in Louisiana". Mower County Transcript. Lansing, Minnesota. October 26, 1887. p. 7. Retrieved August 24, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 35

- ^ a b Fernández-Partagás, p. 37

- ^ United States Life-Saving Service (1889). Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1888. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 25–27. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- ^ Pouliot, Richard A.; Julie J. Pouliot (1986). Shipwrecks on the Virginia Coast and the Men of the United States Life-Saving Service. Tidewater Publishers: Centreville MD. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-0-87033-352-1.

- ^ Fernández-Partagás, p. 38

- ^ a b c Fernández-Partagás, p. 40

- ^ Brown, Daniel P. (February 1, 2017). Hurricane Otto (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Papin, Philippe P. (March 20, 2023). Hurricane Bonnie (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- General

- Fernández-Partagás, José; Diaz, Henry F. (1996). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources: Year 1887 (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 22, 2023.