Humacao (Spanish pronunciation: [umaˈkao]) is a city and municipality in Puerto Rico located in the eastern coast of the island, north of Yabucoa; south of Naguabo; east of Las Piedras; and west of Vieques Passage. Humacao is spread over 12 barrios and Humacao Pueblo (the downtown area and the administrative center of the city). It is part of the San Juan-Caguas-Guaynabo Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Humacao

Municipio Autónomo de Humacao | |

|---|---|

City and Municipality | |

From top, left to right: Downtown Humacao from the city hall; Palmas del Mar; Humacao Co-Cathedral; and the Humacao Monument | |

| Nicknames: "La Perla del Oriente", "La Ciudad Gris", "Roye Huesos" | |

| Anthem: "Humacao, Hijo del Taíno Bravío" | |

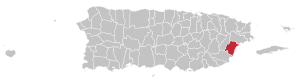

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Humacao Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 18°08′59″N 65°49′39″W / 18.14972°N 65.82750°W | |

| Sovereign state | United States |

| Commonwealth | Puerto Rico |

| European settlement | 16th century |

| Founded | April 5, 1722 |

| Named for | Humaka |

| Barrios | 13 barrios |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Julio Geigel (PNP) |

| • Senatorial dist. | 7 – Humacao |

| • Representative dist. | 35 |

| Area | |

• Total | 55.46 sq mi (143.63 km2) |

| • Land | 45 sq mi (117 km2) |

| • Water | 10.28 sq mi (26.63 km2) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

• Total | 50,896 |

| • Rank | 14th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 920/sq mi (350/km2) |

| • Racial groups (2000 Census)[2] | 69.7% White 12.9% Black 0.4% American Indian/An 0.3% Asian 0.0% Native Hawaiian/Pi 9.7% Some other race 6.9% Two or more races |

| Demonym | Humacaeños |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| ZIP Codes | 00791, 00792, 00741 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

History

editThe region of what is now Humacao belonged to the Taíno region of Humaka, which covered a portion of the southeast coast of Puerto Rico.[3] The region was led by cacique Jumacao (also referred to as "Macao").[4] The Taíno settlement was located on the shores of what is called now the Humacao River. It is believed that the Taíno chief Jumacao was the first "cacique" to learn to read and write in Spanish, since he wrote a letter to the King of Spain Charles I complaining about how the Governor of the island wasn't complying with their peace agreement. In the letter, Jumacao argued that their people were virtually prisoners of Spain. It is said that King Charles was so moved by the letter that he ordered the Governor to obey the terms of the treaty.[5][6][self-published source]

During the early 16th century, the region was populated by cattle ranchers. However, since most of them officially resided in San Juan, a settlement was never officially organized. At the beginning of the 18th century, specifically around 1721–1722, the first official settlement was constituted in the area. Most of the residents at the time were immigrants from the Canary Islands, but due to attacks from Caribs, pirates, and other settlers, some of them moved farther into the island in what is now Las Piedras.[7] Still, some settlers remained and by 1776, historian Fray Íñigo Abbad y Lasierra visited the area and wrote about the population there. By 1793, the church was recognized as parish and the settlement was officially recognized as town.[5]

By 1894, Humacao was recognized as a city. Due to its thriving population, buildings and structures like a hospital, a theater, and a prison were built in the city. In 1899, after the United States invasion of the island as a result of the Spanish–American War, the municipality of Las Piedras was annexed to Humacao. This lasted until 1914, when the Legislative Assembly of Puerto Rico voted on splitting both towns again.[7]

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became a territory of the United States. In 1899, the United States Department of War conducted a census of Puerto Rico finding that the population of Humacao was 14,313.[8]

Humacao was led by mayor Marcelo Trujillo Panisse for over a decade. A basketball star in his early years, Trujillo has pushed for the development of infrastructure facilities for sports and the fine arts in the city. In March 2008, a new Roman Catholic diocese was established as the Fajardo-Humacao diocese. Its first bishop is Monsignor Eusebio 'Chebito' Ramos Morales, a maunabeño who was rector of the Humacao's main parish in the 1990s.

In 2019, Luis Raul Sanchez became interim mayor of Humacao after Marcelo Trujillo Panisse died in September 2019.[9]

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico. Punta Santiago in Humacao saw a six-foot storm surge. The hurricane caused destruction of homes and infrastructure.[10]

Geography

editHumacao is located in the southeast coast of Puerto Rico. It is bordered by the municipalities of Naguabo to the north, Yabucoa to the south, and Las Piedras to the west. The Atlantic Ocean borders the city in the east. Humacao is located in the region of the Eastern Coastal Plains, with most of its territory being flat. There are minor elevations to the southwest, like Candelero Hill, and northwest, like Mabú. Humacao's territory covers 45 square miles (117 km2).[5] Two islands belong to Humacao: Cayo Santiago and Cayo Batata.[11]

Water features

editHumacao's hydrographic system consists of many rivers and creeks like Humacao, Antón Ruíz, and Candelero. Some of its creeks are Frontera, Mariana, and Del Obispo, among many others.[5]

In 2019, updated flood zone maps show that Humacao is extremely vulnerable to flooding, along with Toa Baja, Rincón, Barceloneta, and Corozal. Located where most cyclones enter the island, Humacao is one of the most vulnerable areas of Puerto Rico.[12] Humacao was working on flood mitigation plans and shared that its barrios located on the coast; Antón Ruíz, Punta Santiago, Río Abajo, Buena Vista and Candelero Abajo barrios, are extremely vulnerable to flooding and destruction.[13]

Barrios

editLike all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Humacao is subdivided into barrios. The municipal buildings, central square and large Catholic church are located in a small barrio referred to as "el pueblo", near the center of the municipality.[14][15][16][17]

Sectors

editBarrios (which are, in contemporary times, roughly comparable to minor civil divisions)[18] and subbarrios,[19] are further subdivided into smaller areas called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[20][21][22]

Special Communities

editComunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Humacao: Antón Ruiz, Obrera neighborhood, Cotto Mabú-Fermina, Buena Vista, Parcelas Aniseto Cruz in Candelero Abajo, Parcelas Martínez in Candelero Abajo, Cataño, Punta Santiago, Verde Mar, and Cangrejos.[23][24]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 14,313 | — | |

| 1910 | 26,678 | 86.4% | |

| 1920 | 20,229 | −24.2% | |

| 1930 | 25,466 | 25.9% | |

| 1940 | 29,833 | 17.1% | |

| 1950 | 34,853 | 16.8% | |

| 1960 | 33,381 | −4.2% | |

| 1970 | 36,023 | 7.9% | |

| 1980 | 46,134 | 28.1% | |

| 1990 | 55,203 | 19.7% | |

| 2000 | 59,035 | 6.9% | |

| 2010 | 58,466 | −1.0% | |

| 2020 | 50,896 | −12.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] 1899 (shown as 1900)[26] 1910–1930[27] 1930–1950[28] 1960–2000[29] 2010[16] 2020[30] | |||

Tourism

editTo stimulate local tourism, the Puerto Rico Tourism Company launched the Voy Turistiendo ("I'm Touring") campaign, with a passport book and website. The Humacao page lists Reserva Natural de Humacao, its Pueblo with historic architecture, and its cuisine, specifically Granito, as places and things of interest.[32]

According to a news article by Primera Hora, there are 8 beaches in Humacao including Punta Santiago.[33] Palmas del Mar Beach in Humacao is considered a dangerous beach due to its strong currents.[34]

Due to its location on the coast and relative short distance from the capital, Humacao is a frequent stop for tourists. One of the most notable tourist mainstays is the Palmas del Mar resort, which is Puerto Rico's largest resort. This mega-resort is composed of over 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land and occupies the entire southeastern portion of Humacao. The resort contains tennis courts, two world-class golf courses, beach access, several restaurants and a riding center.

Aside from the beaches at the Palmas del Mar resort, Humacao has other beaches. The most popular ones are Punta Santiago, Buena Vista, Punta Candelero, and El Morrillo.[7] The Candelero Beach Resort, built in 1973, with its 107 rooms, 25 which are suites, was purchased and revitalized by the Suarez family.[35]

The Astronomical Observatory at the University of Puerto Rico at Humacao,[36] Casa Roig, the Guzmán Ermit, the Humacao Wildlife Refuge, and the Church Dulce Nombre de Jesús may be classed as other places of interest.

In the 1980s, the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources established the Humacao Nature Reserve (also called the Punta Santiago Nature Reserve) in the municipality.[37] The Palmas del Mar Tropical Forest is also located in Humacao.[38]

Economy

editBurlington in Humacao employs under 100 people and reopened its doors in March 2019. The store had been shuttered since Hurricane Maria destroyed it on September 19, 2017.[39]

Culture

editFestivals and events

editHumacao celebrates its patron saint festival in December. The Fiestas Patronales Inmaculada Concepcion de Maria is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[11]

The Breadfruit Festival (Festival de la Pana) is celebrated during the first weekend of September. It is organized by the Mariana's Recreational and Cultural Association (ARECMA), a community organization of the Mariana barrio. Its main theme is about the preparation of dishes whose main ingredient is breadfruit. Typical Puerto Rican music, crafts and foods as well as other cultural and sports activities can also be enjoyed. Most years it has been held at one of the highest elevations within the sector with views to Humacao, Las Piedras, Naguabo, Vieques and Yabucoa.

Humacao Grita is an urban art festival held in November.[40][41]

Other festivals and events celebrated in Humacao include:[42]

- Three Kings’ Day- January

- Festival of the Cross – May

- Flat-bottom Boat Festival – June

- Saint Cecilia Festival (patron saint of musicians) – November

- Catholic Church Community Festival – December

Sports

editThe Grises basketball team (Humacao Grays), founded in 2005, belongs to Puerto Rico's National Superior Basketball league. In 2010, they changed their name to the Caciques de Humacao. They play at the new Humacao Coliseum.

The Grises is also a Double A class amateur baseball team that has won one championship (1951) and four time runners-up in (1950, 1960, 1965 and 1967).

Government

editLike all municipalities in Puerto Rico, Humacao is administered by a mayor. In June 2022, Julio Geigel was elected mayor of Humacao.[43] Before then Luis Raul Sanchez got into office, after Marcelo Trujillo Panisse died in September 2019.[9] The former mayor was Marcelo Trujillo, of the Popular Democratic Party (PPD) was elected at the 2000 general election and served for many years. In the 2020 general election Luis Raul was defeated by Reinaldo (Rey) Vargas Rodríguez (PNP) by a margin of 4 points.[44][45] However, on May 5, 2022, Vargas was arrested by the FBI on corruption, bribery, and extortion charges.[46] and was subsequently removed from his position.

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VII, which is represented by two Senators. In 2012, Jorge Suárez and José Luis Dalmau were elected as District Senators.[47]

FBI satellite office

editHealthcare

editHumacao has three secondary care hospitals HIMA-San Pablo Humacao, Menonita (Hospital Oriente), and Ryder Memorial Hospital.

Symbols

editThe municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[49]

Flag

editIt consists of three horizontal stripes: gold that stands for Chief Jumacao's crown, red that symbolizes the coat of arms and the green that represents the arrows used by the Taínos.[50]

Coat of arms

editThe coat of arms mainly consists of two colors, gold and green but also has gules. The gold represents the sun, Humacao is located in the island were the sun rises. Green symbolizes the native Indian heritage as well as the natural tropical valley where the city is located. The shield itself represents Humacao's native and Indian name origin. The coat of arms was designed by Roberto Brascochea Lota in 1975 and approved by Humacao on November 13, 1975.[50]

Transportation

editHumacao's airport is no longer used for daily flights to Vieques and Culebra as it was in the past. It is now used for private flights.

Humacao is served by two freeways and one tolled expressway, therefore is one of a few cities in Puerto Rico with good access. Puerto Rico Highway 30, Autopista Cruz Ortiz Stella, serves as the main highway coming from the west (Caguas, Las Piedras), while Puerto Rico Highway 53 serves from the north (Fajardo, Naguabo) and south (Yabucoa). Puerto Rico Highway 60, the Carretera Dionisio Casillas, is a short freeway located entirely in Humacao, and has exits serving downtown Humacao and Anton Ruiz.

Puerto Rico Highway 3, the main highway bordering the east coastline of Puerto Rico from San Juan, passes through Humacao and has its only alt route in the town, known locally as the Bulevar del Rio (River Boulevard) where it has access to the main judiciary center of the city, as well as a future theatre that is being built, the Centro de Bellas Artes de Humacao (Humacao Fine Arts Center). The alt route allows people to pass by the downtown area, as PR-3 enters into the downtown and business center of the town.

Puerto Rico Highway 908 is another important highway, which begins at PR-3 and intersects PR-30 and has access to the University of Puerto Rico at Humacao, as well as some main schools in the municipality.

Humacao, together with San Juan and Salinas, is one of three municipalities in Puerto Rico that has controlled-access highways leaving its boundaries in all directions (in this case north to Naguabo and south to Yabucoa via PR-53 and west to Las Piedras via PR-30)

There are 68 bridges in Humacao.[51]

Education

editThere are various elementary and high school facilities, three of which were recognized by the Middle States Association of Secondary Schools and each has its own National Honor Society chapters. These include Colegio San Antonio Abad, founded in 1957 and operated by the Benedictine monks of the Abadía San Antonio Abad.[52]

The University of Puerto Rico at Humacao, formerly the CUH, educates over 4,000 students and is well known for its sciences, producing many of the island's most skilled microbiologists, marine biologists, wildlife biologists and chemists at the undergraduate level. It also manages an astronomical observatory where many tourists and locals come visit and view the stars and planets and the Museo Casa Roig where arts expositions and cultural events are celebrated.

Notable natives and residents

edit- Rita Moreno, Academy Award-winning actress

- Edwin Núñez, professional baseball player

- Luis Rafael Sánchez, novelist and author

- Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez, member of the Chicago City Council

- Eddie Miró, TV personality

- Julio M. Fuentes, US Circuit Court judge

- Tito Rojas, salsa singer

- Adamari López, actress

- Papulin Moyett, periodista y locutor de radio

- Jaquira Díaz, author, journalist

- Cosculluela, rapper, songwriter

- Eladio Carrión, rapper, songwriter

- Jumacao, Taino Cacique

- Benito Pastoriza Iyodo, poet, narrator, and essayist

- Carlos Ponce, actor

- Luis Antonio "Yoyo Boing" Rivera, actor and comedian

- Diplo,comedian

- Jerry Rivera, singer and dancer

- Junior Ortiz, former Major League Baseball player

- Raul Casanova, former Major League Baseball player

- Rafael Orellano, former professional baseball player

- Jantony Ortiz, professional boxer

- José Estrada Jr., former professional wrestler

- Ana Otero, Pianist, composer, arranger, conductor, activist.[53]

- Jon Z, rapper, songwriter

- Luis Enrique Juliá, composer

- Yomo, rapper, singer

Gallery

edit-

Moon jellyfish off the coast of Humacao

-

View of Vieques Island from Humacao

-

The Centro de Arte Angel "Lito" Peña Plaza in 2020, which used to be the Alcaldía or town hall of Humacao is on the US National Register of Historic Places.

-

A beach in Humacao

-

Fishing from a pier in Humacao

-

Large planter in Humacao barrio-pueblo

-

Palmas del Mar Beach

-

Square in the Pueblo of Humacao

-

Underwater scene off the coast of Humacao

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Ethnicity 2000 census" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ "Gobierno Tribal del Pueblo Jatibonicu Taíno de Puerto Rico". Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Schimmer, Russell (2010). "Genocide Studies Program: Puerto Rico". Yale University. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Humacao... la Perla del Oriente". ProyectoSalonHogar. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- ^ "El agua del paraíso (Spanish Edition)"; by: Benito Pastoriza Iyodo; Publisher: Xlibris (April 21, 2008); ISBN 1-4363-2567-6; ISBN 978-1-4363-2567-7[self-published source]

- ^ a b c "Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico: Humacao – Fundación e historia". Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office. Washington : Govt. print. off. p. 160.

- ^ a b "Confirmadas las aspiraciones políticas de Luis Raúl Sánchez – Periódico El Oriental". Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ "María, un nombre que no vamos a olvidar. El huracán María dejó irreconocible a Humacao" [Maria, a name we will never forget. Humacao is unrecognizable after Hurricane Maria]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). June 13, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "Humacao Municipality". enciclopediapr.org. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ Alvarado León, Gerardo E. "Sobre 250,000 estructuras están en zonas inundables" (PDF). Junta de Planificación – Gobierno de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). El Nuevo Día. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ Solano Quintana, Bárbara. "Piden participación ciudadana para revisión del plan de mitigación de Humacao" (PDF). El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2019 – via Junta de Planificación Gobierno de Puerto Rico.

- ^ Picó, Rafael; Buitrago de Santiago, Zayda; Berrios, Hector H. (1969). Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social, por Rafael Picó. Con la colaboración de Zayda Buitrago de Santiago y Héctor H. Berrios. San Juan Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Puerto Rico,1969. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Gwillim Law (May 20, 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "Map of Humacao at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ "P.L. 94-171 VTD/SLD Reference Map (2010 Census): Humacao Municipio, PR" (PDF). www2.census.gov. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997–2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza:Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997–2004 (Primera edición ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ "Comunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). August 8, 2011. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Report of the Census of Porto Rico 1899". War Department Office Director Census of Porto Rico. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930 1920 and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Pasaporte: Voy Turisteando (in Spanish). Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico. 2021.

- ^ "Las 1,200 playas de Puerto Rico [The 1200 beaches of Puerto Rico]". Primera Hora (in Spanish). April 14, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ "Conoce las 11 playas más peligrosas de Puerto Rico [Know the 11 most dangerous beaches in Puerto Rico]". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). July 4, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "Revitalizan el Candelero Beach Resort en Humacao". El Nuevo Dia (in Spanish). December 6, 2018. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ "Observatorio Astronómico". Universidad de Puerto Rico en Humacao. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ^ Fotogalería: Paseo por la Reserva Natural de Humacao. Archived March 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Jose E. Maldonado. Mi Puerto Rico Verde. September 19, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Forest at Palmas del Mar". Para la Naturaleza (in European Spanish). May 9, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Se acabó la espera: reabre sus puertas Burlington en Humacao" (in Spanish). El Oriental PR. March 15, 2019. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ ""Humacao Grita" Festival de arte urbano este domingo". El Foro de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). November 14, 2019. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ ""HUMACAO GRITA" FESTIVAL DE ARTE URBANO ESTE DOMINGO". Conéctate TV (in Spanish). November 14, 2019. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Festivales, Eventos y Actividades en Puerto Rico". Puerto Rico Hoteles y Paradores (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ "Julio Geigel será el nuevo alcalde de Humacao: "Es momento de unirnos para trabajar por el bien" del municipio". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ "CEE Event". elecciones2020.ceepur.org. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Juramenta Reinaldo Vargas como nuevo alcalde de Humacao | Metro". www.metro.pr. January 11, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "El FBI Arresta a los Alcaldes de Humacao y Aguas Buenas". May 5, 2022. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General Archived January 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- ^ "San Juan—FBI". Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "HUMACAO". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Humacao Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ "Historia". Colegio San Antonio Abad.

- ^ "Ana Otero Hernandez bio]" (in Spanish). San Juan, Puerto Rico: National Foundation for Popular Culture. Archived from the original on October 19, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2019.