Henryk Mikołaj Górecki (/ɡəˈrɛtski/ gə-RET-skee, Polish: [ˈxɛnrɨk miˈkɔwaj ɡuˈrɛt͡skʲi] ;[1] 6 December 1933 – 12 November 2010)[2][3] was a Polish composer of contemporary classical music. According to critic Alex Ross, no recent classical composer has had as much commercial success as Górecki.[4] He became a leading figure of the Polish avant-garde during the post-Stalin cultural thaw.[5][6] His Anton Webern-influenced serialist works of the 1950s and 1960s were characterized by adherence to dissonant modernism and influenced by Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen,[7] Krzysztof Penderecki and Kazimierz Serocki.[8] He continued in this direction throughout the 1960s, but by the mid-1970s had changed to a less complex sacred minimalist sound, exemplified by the transitional Symphony No. 2 and the Symphony No. 3 (Symphony of Sorrowful Songs). This later style developed through several other distinct phases, from such works as his 1979 Beatus Vir,[9] to the 1981 choral hymn Miserere, the 1993 Kleines Requiem für eine Polka[10] and his requiem Good Night.[11]

Henryk Górecki | |

|---|---|

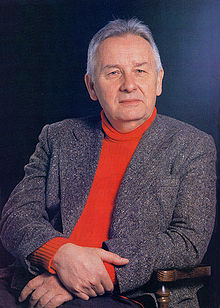

Górecki in 1993 | |

| Born | Henryk Mikołaj Górecki 6 December 1933 Czernica, Silesia, Poland |

| Died | 12 November 2010 (aged 76) Katowice, Silesia, Poland |

| Alma mater | Karol Szymanowski Academy of Music |

| Era | Contemporary |

| Known for | Symphony of Sorrowful Songs |

| Works | List of works |

| Spouse | Jadwiga Rurańska (pianist) |

| Children | Anna Górecka Mikołaj Górecki |

| Signature | |

Górecki was largely unknown outside Poland until the late 1980s.[12] In 1992, 15 years after it was composed, a recording of his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs with soprano Dawn Upshaw and conductor David Zinman, released to commemorate the memory of those lost during the Holocaust, became a worldwide commercial and critical success, selling more than a million copies and vastly exceeding the typical lifetime sales of a recording of symphonic music by a 20th-century composer. Commenting on its popularity, Górecki said, "Perhaps people find something they need in this piece of music ... somehow I hit the right note, something they were missing. Something somewhere had been lost to them. I feel that I instinctively knew what they needed."[13] This popular acclaim did not generate wide interest in Górecki's other works,[14] and he pointedly resisted the temptation to repeat earlier success, or compose for commercial reward. Nevertheless, his music drew the attention of Australian film director Peter Weir, who used a section of Symphony No. 3 in his 1993 film Fearless.

Apart from two brief periods studying in Paris and a short time living in Berlin, Górecki spent most of his life in southern Poland.

Biography

editEarly years

edit|

I was born in Silesia....It is old Polish land. But there were always three cultures present: Polish, Czech, and German. The folk art, all the art, had no boundaries. Polish culture is a wonderful mixture. When you look at the history of Poland, it is precisely the multiculturalism, the presence of the so-called minorities that made Poland what it was. The cultural wealth, the diversity mixed and created a new entity.[15] |

| — Henryk Górecki |

Henryk Górecki was born on 6 December 1933, in the village of Czernica, in present-day Silesian Voivodeship, southwest Poland. His family lived modestly, though both parents had a love of music. His father Roman (1904–1991) worked at the goods office of a local railway station, but was an amateur musician, while his mother Otylia (1909–1935), played piano. Otylia died when her son was just two years old,[16] and many of his early works were dedicated to her memory.[17] Henryk developed an interest in music from an early age, though he was discouraged by both his father and new stepmother to the extent that he was not allowed to play his mother's old piano. He persisted, and in 1943 was allowed to take violin lessons with Paweł Hajduga, a local amateur musician, instrument maker, sculptor, painter, poet and chłopski filozof (peasant philosopher).[18]

In 1937, Górecki fell while playing in a neighbor’s yard and dislocated his hip. The resulting suppurative inflammation was misdiagnosed by a local doctor, and delay in proper treatment led to tubercular complications in the bone. The illness went largely untreated for two years, by which time permanent damage had been sustained. He spent the following twenty months in a hospital in Germany, where he underwent four operations.[19] Górecki continued to suffer ill health throughout his life and as a result said he had "talked with death often".[20]

In the early 1950s, Górecki studied in the Szafrankowie Brothers State School of Music in Rybnik. Between 1955 and 1960, he studied at the State Higher School of Music in Katowice. In 1965 He joined the faculty of his alma mater in Katowice, where he was made a lecturer in 1968, and then rose to provost before resigning in 1979.[21]

Rydułtowy and Katowice

editBetween 1951 and 1953, Górecki taught 10- and 11-year-olds at a school suburb of Rydułtowy, in southern Poland.[18] In 1952, he began a teacher training course at the Intermediate School of Music in Rybnik, where he studied clarinet, violin, piano, and music theory. Through intensive studying, Górecki finished the four-year course in just under three years. During this time, he began to compose his own pieces, mostly songs and piano miniatures. Occasionally, he attempted more ambitious projects—in 1952, he adapted the Adam Mickiewicz ballad Świtezianka, though it was left unfinished.[22] Górecki's life during this time was often difficult. Teaching posts were generally badly paid, while the shortage economy made manuscript paper at times difficult and expensive to acquire. With no access to radio, Górecki kept up to date with music by weekly purchases of such periodicals as Ruch muzyczny (Musical Movement) and Muzyka, and by purchasing at least one score a week.[23]

Górecki continued his formal study of music at the Academy of Music in Katowice,[24] where he studied under the composer Bolesław Szabelski, a former student of Karol Szymanowski. Szabelski drew much of his inspiration from Polish highland folklore.[1] He encouraged Górecki's growing confidence and independence by giving him considerable space in which to develop his own ideas and projects; several of Górecki's early pieces were straightforwardly neo-classical,[25] during a period when Górecki was also absorbing the techniques of twelve-tone serialism.[26] He graduated from the Academy with honours in 1960.[citation needed]

Professorship

editIn 1975, Górecki was promoted to professor of composition at the State Higher School of Music in Katowice, where his students included Eugeniusz Knapik, Andrzej Krzanowski, Rafał Augustyn and his son, Mikołaj.[24] Around this time, he came to believe the Polish Communist authorities were interfering too much in the academy's activities, and called them "little dogs always yapping".[1] As a senior administrator but not a member of the Party, he was in almost perpetual conflict with the authorities in his efforts to protect his school, staff and students from undue political influence.[24] In 1979, he resigned from his post in protest at the government's refusal to allow Pope John Paul II to visit Katowice,[27] and formed a local branch of the "Catholic Intellectuals Club", an organisation devoted to the struggle against the Communist Party (Polish United Workers' Party).[1]

In 1981, he composed his Miserere for a large choir in remembrance of police violence against the Solidarity movement.[10] In 1987, he composed Totus Tuus for John Paul II's visit to Poland.

Style and compositions

editGórecki's music covers a variety of styles, but tends towards relative harmonic and rhythmical simplicity. He is considered a founder of the New Polish School.[28][29] According to Terry Teachout, Górecki's "more conventional array of compositional techniques includes both elaborate counterpoint and the ritualistic repetition of melodic fragments and harmonic patterns."[30]

Górecki's first works, dating from the last half of the 1950s, were in the avant-garde style of Webern and other serialists of that time. Some of these twelve-tone and serial pieces include Epitaph (1958), First Symphony (1959), and Scontri (1960).[31] At that time, Górecki's reputation was not lagging behind that of Penderecki and his status was confirmed in 1960s when Monologhi won a first prize. Even until 1962, he was firmly ensconced in the minds of the Warsaw Autumn public as a leader of the Polish Modern School, alongside Penderecki.[32]

Danuta Mirka has shown that Górecki's compositional techniques in the 1960s were often based on geometry, including axes, figures, one- and two-dimensional patterns, and especially symmetry. She proposes the term "geometrical period" for his works between 1962 and 1970. Building on Krzysztof Droba's classifications, she further divides this period into two phases: "the phase of sonoristic means" (1962–63) and "the phase of reductive constructicism" (1964–70).[33]

During the mid-1960s and early 1970s, Górecki progressively moved away from his early career as radical modernist, and began to compose in a more traditional, romantic mode of expression. His change of style was viewed as an affront to the then avant-garde establishment, and though he continued to receive commissions from various Polish agencies, by the mid-1970s Górecki was no longer regarded as a composer of importance. In the words of one critic, his "new material was no longer cerebral and sparse; rather, it was intensely expressive, persistently rhythmic and often richly colored in the darkest of orchestral hues".[34]

Early modernist works

editThe first public performances of Górecki's music in Katowice in February 1958 programmed works clearly displaying the influence of Szymanowski and Bartók. The Silesian State Philharmonic in Katowice held a concert devoted entirely to the 24-year-old Górecki's music. The event led to a commission to write for the Warsaw Autumn Festival. The Epitafium (Epitaph) he submitted marked a new phase in his development,[13] and was said to represent "the most colourful and vibrant expression of the new Polish wave".[35] The festival announced Górecki's arrival on the international scene, and he quickly became a favorite of the West's avant-garde musical elite.[34] In 1991, the music critic James Wierzbicki wrote that at this time "Górecki was seen as a Polish heir to the new aesthetic of post-Webernian serialism, with his taut structures, lean orchestrations and painstaking concern for the logical ordering of pitches".[34]

Górecki wrote his First Symphony in 1959, and graduated with honours from the Academy the next year.[24] At the 1960 Warsaw Autumn Festival, his Scontri for orchestra caused a sensation among critics due to its use of sharp contrasts and harsh articulations.[24][36] By 1961, Górecki was at the forefront of the Polish avant-garde, having absorbed the modernism of Webern, Iannis Xenakis and Pierre Boulez, and his Symphony No. 1 gained international acclaim at the Paris Biennial Festival of Youth. He moved to Paris to continue his studies, and while there was influenced by contemporaries including Olivier Messiaen, Roman Palester, and Karlheinz Stockhausen.[7]

Górecki began to lecture at the Academy of Music in Katowice in 1968, where he taught score-reading, orchestration and composition. In 1972, he was promoted to assistant professor,[24] and developed a fearsome reputation among his students for his often blunt personality. According to the Polish composer Rafał Augustyn, "When I began to study under Górecki it felt as if someone had dumped a pail of ice-cold water over my head. He could be ruthless in his opinions. The weak fell by the wayside but those who graduated under him became, without exception, respected composers".[1] Górecki admits, "For quite a few years, I was a pedagogue, a teacher in the music academy, and my students would ask me many, many things, including how to write and what to write. I always answered this way: If you can live without music for 2 or 3 days, then don't write...It might be better to spend time with a girl or with a beer...If you cannot live without music, then write.”[37] Due to his commitments as a teacher and also because of bouts of ill health, he composed only intermittently during this period.[38]

Move from modernism

editBy the early 1970s, Górecki had begun to move away from his earlier radical modernism, and was working toward a more traditional mode of expression dominated by the human voice. His change of style affronted the avant-garde establishment, and although various Polish agencies continued to commission works from him, Górecki ceased to be viewed as an important composer. One critic later wrote, "Górecki's new material was no longer cerebral and sparse; rather, it was intensely expressive, persistently rhythmic and often richly colored in the darkest of orchestral hues".[34] Górecki progressively rejected the dissonance, serialism and sonorism that had brought him early recognition, and pared and simplified his work. He began to favor large slow gestures and the repetition of small motifs.[39]

The Symphony No. 2, "Copernican" (II Symfonia Kopernikowska), was written in 1972 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the birth of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. Written in a monumental style for solo soprano, baritone, choir and orchestra, it features text from Psalms no. 145, 6 and 135 as well as an excerpt from Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.[40] It is in two movements, and a typical performance lasts 35 minutes. It was commissioned by the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York, and presented an early opportunity for Górecki to reach an audience outside Poland. As was usual, he undertook extensive research on the subject, and was in particular concerned with the philosophical implications of Copernicus's discovery, not all of which he viewed as positive.[41] As the historian Norman Davies commented, "His discovery of the earth's motion round the sun caused the most fundamental revolutions possible in the prevailing concepts of the human predicament".[42]

By the mid-1980s, Górecki began to attract a more international audience, and in 1989 the London Sinfonietta held a weekend of concerts in which his work was played alongside that of the Russian composer Alfred Schnittke.[43] In 1990, the American Kronos Quartet commissioned and recorded his First String Quartet, Already It Is Dusk, Op. 62, an occasion that marked the beginning of a long relationship between the quartet and Górecki.[44]

Górecki's most popular piece is his Third Symphony, also known as the "Symphony of Sorrowful Songs" (Symfonia pieśni żałosnych). The work is slow and contemplative, and each of its three movements is for orchestra and solo soprano. The libretto for the first movement is taken from a 15th-century lament, while the second movement uses the words of a teenage girl, Helena Błażusiakówna (Helena Błażusiak), which she wrote on the wall of a Gestapo prison cell in Zakopane to invoke the protection of the Virgin Mary.[45]

The third uses the text of a Silesian folk song which describes the pain of a mother searching for a son killed in the Silesian Uprisings.[46] The symphony's dominant themes are motherhood and separation through war. While the first and third movements are written from the perspective of a parent who has lost a child, the second is from that of a child separated from a parent.

The completion of Górecki's Fourth Symphony, subtitled "Tansman Episodes", was delayed for many years, partly by Górecki's unease at his newfound fame. Indeed, it had not even been orchestrated when he died in 2010, and his son Mikołaj completed it after his death from the piano score and notes left behind by his father.[47] It uses similar repetition techniques as the Second and Third Symphonies, but to very different effect; for example, its opening consists of a series of very loud, repeated cells that together spell out the name of the composer Alexandre Tansman via a musical cryptogram, punctuated with heavy strokes on the bass drum and clashing bitonality between the chords of A and E-flat.[48]

Later works

editDespite the Third Symphony's success, Górecki resisted the temptation to compose again in that style, and, according to AllMusic, continued to work, not to further his career or reputation, but largely "in response to inner creative dictates".[49]

In February 1994, the Kronos Quartet performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music four concerts honoring postmodern revival of interest in new music. The first three concerts featured string quartets and the works of three living composers: two Americans (Philip Glass and George Crumb) and one Pole (Górecki).[30]

Górecki's later work includes a 1992 commission for the Kronos Quartet, Songs are Sung; Concerto-Cantata (written in 1992 for flute and orchestra); and Kleines Requiem für eine Polka (1993 for piano and 13 instruments). Concerto-Cantata and Kleines Requiem für eine Polka have been recorded by the London Sinfonietta and the Schönberg Ensemble, respectively.[50] Songs are Sung is his third string quartet, inspired by a poem by Velimir Khlebnikov. When asked why it took almost 13 years to finish, he replied, "I continued to hold back from releasing it to the world. I don’t know why."[51]

Last decade

editDuring the last decade of his life, Górecki suffered from frequent illnesses.[52] His Symphony No. 4 (oP. 85, 2006) was due to be premiered in London in 2010 by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, but the event was cancelled due to the composer's ill health.[52][53] He died on 12 November 2010, in his home city of Katowice, from complications arising from a lung infection.[54] Reacting to his death, the head of the Karol Szymanowski Academy of Music, Professor Eugeniusz Knapik, said "Górecki's work is like a huge boulder that lies in our path and forces us to make a spiritual and emotional effort".[55] Adrian Thomas, professor of music at Cardiff University, said, "The strength and startling originality of Górecki's character shone through his music ... Yet he was an intensely private man, sometimes impossible, with a strong belief in family, a great sense of humour, a physical courage in the face of unrelenting illness, and a capacity for firm friendship".[52] He was married to Jadwiga, a piano teacher. His daughter, Anna Górecka-Stanczyk, is a pianist, and his son, Mikołaj Górecki, is a composer.[56] He was survived by five grandchildren.

President of the Republic of Poland Bronisław Komorowski awarded Górecki the Order of the White Eagle, Poland's highest honour, a month before his death. The Order was presented by Komorowski's wife in Górecki's hospital bed.[2][54][57] Earlier, Górecki received the Order of Polonia Restituta II class and III class and the Order of St. Gregory the Great.

The world premiere of his Symphony No. 4 took place on 12 April 2014. It was performed, as originally scheduled in 2010, by the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, London, but with Andrey Boreyko conducting instead of Marin Alsop.[58] Symphony No. 4 is an extensive, 37-minute composition set for an approximately 100-person orchestra with piano and organ obbligato. The composer left a cryptogram that explains the way he built the theme for the symphony using musical letters from the first and last names of Alexandre Tansman.[59]

In 2004, Górecki left the piano reduction of Two Tristan Postludes and Chorale for orchestra, which received Op. 82. It was orchestrated by his son Mikolaj Górecki and premiered at the Tansman Festival, on October 16, 2016, at the Polish Radio Witold Lutosławski Studio Hall in Warsaw, by Jerzy Maksymiuk and the Sinfonia Varsovia orchestra.[60][61]

Use in film and television

editSome of Górecki's music has been adapted for film soundtracks, most notably fragments of his Symphony of Sorrowful Songs. They are featured in Peter Weir's 1993 film Fearless,[62] Julian Schnabel's 1996 biographical drama film Basquiat,[63] Shona Auerbach's 1996 film Seven, Jaime Marqués's 2007 film Ladrones, Terrence Malick's 2012 experimental romantic drama To the Wonder,[64] Paolo Sorrentino's 2013 art drama film The Great Beauty,[65] Felix van Groeningen's 2018 biographical film Beautiful Boy,[66] and Malick's 2019 historical drama A Hidden Life.[67] It has also appeared on television in numerous TV shows, including the American crime drama television series The Sopranos,[68] American TV series Legion,[69] crime thriller television series The Blacklist,[70] and the historical drama The Crown.[71] In 2017, Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite set the first movement of the Symphony of Sorrowful Songs as a ballet, Flight Pattern. In 2022, she set the whole symphony as a larger work, Light of Passage. French filmmaker Bertrand Blier used Beatus Vir in his 1996 film My Man.

Critical opinion

editWhen placing Górecki in context, musicologists and critics generally compare his work with such composers as Olivier Messiaen and Charles Ives.[72] He himself said that he also felt kindred with such figures as Bach, Mozart and Haydn, though he felt most affinity with Franz Schubert, particularly in terms of tonal design and treatment of basic materials.[72] In the Dutch documentary film series Toonmeesters, of which episode 4 (1994) is about Górecki, he likened playing Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart every day to eating healthy whole grain bread every day. In the same episode he said that in Mozart and Schubert he found many new things, new musical answers.

Since Górecki moved away from serialism and dissonance in the 1970s, he is frequently compared to composers such as Arvo Pärt, John Tavener and Giya Kancheli.[36][72] Although none have admitted to common influence, the term holy minimalism is often used to group these composers, due to their shared simplified approach to texture, tonality and melody, in works often reflecting deeply held religious beliefs. Górecki's modernist techniques are also compared to those of Igor Stravinsky, Béla Bartók, Paul Hindemith and Dmitri Shostakovich.[30]

In 1994, Boguslaw M. Maciejewski published the first biography of Górecki, Górecki – His Music And Our Times.[73] It includes a great deal of detail about his life and work, including that he achieved cult status thanks to valuable exposure on Classic FM.

Discussing his audience in a 1994 interview, Górecki said,

I do not choose my listeners. What I mean is, I never write for my listeners. I think about my audience, but I am not writing for them. I have something to tell them, but the audience must also put a certain effort into it. But I never wrote for an audience and never will write for because you have to give the listener something and he has to make an effort in order to understand certain things. If I were thinking of my audience and one likes this, one likes that, one likes another thing, I would never know what to write. Let every listener choose that which interests him. I have nothing against one person liking Mozart or Shostakovich or Leonard Bernstein, but doesn't like Górecki. That's fine with me. I, too, like certain things.[37]

Górecki received an honorary doctorate from Concordia University, in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Concordia professor Wolfgang Bottenberg called him one of the "most renowned and respected composers of our time", and said that Górecki's music "represents the most positive aspects of the closing years of our century, as we try to heal the wounds inflicted by the violence and intolerance of our times. It will endure into the next millennium and inspire other composers".[74] In 2007, Górecki claimed 32nd place on the list of Top 100 Living Geniuses compiled by The Daily Telegraph.[75] In 2008, he received an honorary doctorate from the Academy of Music in Kraków. At the awarding ceremony a selection of his choral works was performed by the choir of the city's Franciscan Church.[76]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c d e Perlez, Jane (27 February 1994). "Henryk Gorecki". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Polish composer Henryk Gorecki dies at the age of 76". BBC News. 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Polish composer Henryk Gorecki dies aged 76". Reuters. 12 November 2010. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ Ross, Alex (30 January 2015). "Cult Fame and Its Discontents". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015.

No classical composer in recent memory, not even the inescapable Philip Glass, has had a commercial success to rival that of the late Polish master Henryk Górecki.

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 12.

- ^ Kubicki, Michal. "H.M. Górecki at 75". The News.pl, 8 December 2008 (archive from 2 March 2009, retrieved on 26 August 2015).

- ^ a b Thomas (1997), p. 17

- ^ Mellers (1989), p. 23.

- ^ Cummings (2000), 241[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b Thomas (2005), p. 262

- ^ Morin (2002), p. 357.

- ^ Thomas (2001).

- ^ a b Steinberg (1995), p. 171

- ^ Steinberg (1995), p. 170.

- ^ "The Twentieth Century: On Life and Music: A Semi-Serious Conversation". The Musical Quarterly, 82.1, 1998. 73–75[author missing]

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. xiii.

- ^ Howard (1998), pp. 131–133.

- ^ a b Thomas (1997), p. xvi

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. vi.

- ^ Howard (1998), p. 134.

- ^ Slonimsky (2001).

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. xviii.

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 13

- ^ a b c d e f Harley, James & Trochimczyk, Maja. "Henryk Mikołaj Górecki". Polish Music Information Center, November 2001. Retrieved on 6 March 2009.

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 1.

- ^ Thomas (1997), pp. 39–41.

- ^ Lebrecht, Norman. "How Górecki makes his music". La Scena Musicale. 28 February 2007. Retrieved on 4 January 2008.

- ^ Thomas (2005), p. 159.

- ^ "Górecki, Henryk Biography Archived 17 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine". Naxos Records. Retrieved on 1 June 2009.

- ^ a b c Teachout, Terry (1995). "Holy minimalism". Commentary. 99 (4): 50.

- ^ Mirka (2004), p. 305.

- ^ Jacobson (1996), p. [page needed].

- ^ Mirka (2004), p. 329.

- ^ a b c d Wierzbicki, James. "Henryk Gorécki" Archived 14 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 7 July 1991. Retrieved on 24 October 2008.

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 29

- ^ a b Wright (2002), p. 362

- ^ a b Duffie, Bruce. "Composer Henryk-Mikolaj Górecki: A conversation with Bruce Duffie". bruceduffie.com, 24 April 1994. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Williams, Julie. "Henryk Górecki: Composer Profile". MusicWeb International, 2008. Retrieved on 13 December 2008.

- ^ Howard (1998), p. 135.

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 77

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 74

- ^ Davies, Norman. God's Playground: A history of Poland. Oxford, 1981. 150. ISBN 0-19-925339-0

- ^ Thomas (2008), 5:35.

- ^ "Henryk Górecki + Kronos Quartet". Nonesuch Records. Retrieved on 1 June 2009.

- ^ Thomas (1997), p. 82.

- ^ Ellis, David. "Evocations of Mahler" Archived 17 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Naturlaut 4(1): 2–7, 2005. Retrieved 22 June 2007.

- ^ Adrian Thomas, notes to Nonesuch Records' 2016 recording of the symphony, 7559-79503-4

- ^ Thomas, 2016[incomplete short citation]

- ^ "Henryk Górecki: Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved on 13 December 2008.

- ^ "Henryk Mikolaj Górecki". Boosey & Hawkes, February 2007. Retrieved on 24 October 2008.

- ^ Gardner, Charlotte. "String Quartet No. 3 '...songs are sung'". BBC, 22 March 2007. Retrieved on 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Potter, Keith (12 November 2010). "Henryk Górecki obituary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Southbank Centre. Retrieved on 5 February 2010.)

- ^ a b "Polish classical composer Gorecki dies at 76". The Washington Post. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Polish composer of 'Sorrowful Songs' Gorecki dies, aged 76". Deutsche Welle. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ "Polish classical composer Gorecki dies at 76". Deseret News. Associated Press. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Music: No, Mother, do not weep – Inkless Wells, Uncategorized – Macleans.ca". Maclean's. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ The Guardian video of world premiere Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wendland, Andrzej. "The Phenomenon and Mystery of Górecki’s Fourth Symphony – Tansman Episodes". In Trochimczyk (2017), pp. 310–352.

- ^ Wendland, Andrzej (2019). Górecki, Penderecki. Diptych. Los Angeles: Moonrise Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-945938-30-6.

- ^ "Prologue: Tansman – Górecki. World premieres". www.polmic.pl. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Original soundtrack Fearless at AllMusic

- ^ Basquiat at IMDb

- ^ To the Wonder at IMDb

- ^ The Great Beauty at IMDb

- ^ "Songs and music featured in Beautiful Boy". Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "A Hidden Life Soundtrack". Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "The Sopranos Soundtrack". Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ^ "Legion soundtrack. S2 E6 chapter 14". Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "The Blacklist (NBC) Soundtrack". Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "The Crown Soundtrack". Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Thomas (1997), p. 135

- ^ Maciejewski (1994).

- ^ Bottenberg, Wolfgang. "Gorecki, Martin to receive honours". Concordia University, 19 November 1998. Retrieved on 26 October 2008.

- ^ "Top 100 living geniuses". Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Henryk Górecki Receives Honorary Doctorate from Krakow Music Academy". Nonesuch Records (press release), 13 May 2008. Retrieved on 26 October 2008.

Bibliography

edit- Howard, Luke B. (Spring 1998). "Motherhood, 'Billboard' and the Holocaust: Perceptions and Receptions of Górecki's Symphony No. 3". The Musical Quarterly. 82 (1): 131–159. doi:10.1093/mq/82.1.131.

- Jacobson, Bernard (1996). A Polish Renaissance. Twentieth-Century Composers. London: Phaidon. ISBN 0-7148-3251-0.

- Maciejewski, Boguslaw M. (1994). Gorecki – His Music and Our Times. London: Allegro Press. ISBN 0-9505619-6-7.

- Mellers, Wilfrid (March 1989). "Round and about Górecki's Symphony No. 3". Tempo. New Series (168): 22–24. doi:10.1017/S0040298200024906. JSTOR 944854. S2CID 145469868.

- Mirka, Danuta (Summer 2004). "Górecki's Musica geometrica". The Musical Quarterly. 87 (2): 305–332. doi:10.1093/musqtl/gdh013. JSTOR 3600907.

- Morin, Alexander (2002). Classical Music: The Listener's Companion. San Francisco, California: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-638-6.

- Slonimsky, Nicolas, ed. (2001). "Górecki, Henryk (Mikołaj)". Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (8th ed.). New York: Schirmer.

- Steinberg, Michael (1995). The Symphony: A Listener's Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512665-3.

- Thomas, Adrian (1997). Górecki. Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816393-2.. (cloth) ISBN 0-19-816394-0.

- — (2001). "Górecki, Henryk Mikołaj". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11478. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- — (2005). "Polish Music since Szymanowski". Music in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58284-9.

- — (4 December 2008). "Henryk Gorecki" (lecture). London: Gresham College. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010.

- Trochimczyk, Maja, ed. (2017). Górecki in Context: Essays on Music. Moonrise Press. ISBN 978-1-945938-10-8.

- Wright, Stephen (2002). "Arvo Pärt (1935–)". Music of the Twentieth-Century Avant-Garde: A Biocritical Sourcebook. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29689-8.

Further reading

edit- Marek, Tadeusz; Drew, David (March 1989). "Górecki in Interview (1968) – And 20 Years After". Tempo. New Series (168): 25–28. doi:10.1017/S0040298200024918. JSTOR 944855. S2CID 145722754.

- Markiewicz, Leon (July 1962). "Conversation with Henryk Górecki". Polish Music Journal. 6 (2). Translated by Anna Maslowiec. ISSN 1521-6039. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016. Special edition marking Górecki's 70th birthday, consisting of articles exclusively on Górecki.

External links

edit- Media related to Henryk Górecki at Wikimedia Commons

- Henryk Mikolaj Górecki (1933–2010) at IMDb

- Lerchenmusik, Op. 53, Luna Nova Ensemble (Nobuko Igarashi, clarinet; Craig Hultgren, cello; Andrew Drannon, piano)