Haplogroup A is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, which includes all living human Y chromosomes. Bearers of extant sub-clades of haplogroup A are almost exclusively found in Africa (or among the African diaspora), in contrast with haplogroup BT, bearers of which participated in the Out of Africa migration of early modern humans. The known branches of haplogroup A are A00, A0, A1a, and A1b1; these branches are only very distantly related, and are not more closely related to each other than they are to haplogroup BT.

| Haplogroup A | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | 270,000 BP,[1][2] 275,000 BP (303,000-241,000 BP),[3][4] 291,000 BP[5] |

| Coalescence age | 275,000 BP (split with other lineages)[6] |

| Possible place of origin | Northwest Africa, Central Africa[7] |

| Ancestor | Human Y-MRCA (A00-T) |

| Descendants | primary: A00 (AF6/L1284), A0-T (Subclades of these include haplogroups A00a, A00b, A00c, A0, A1, A1a, A1b, A1b1 and BT.) |

Origin

editThough there are terminological challenges to define it as a haplogroup, haplogroup A has come to mean "the foundational haplogroup" (viz. of contemporary human populations); it is not defined by any mutation, but refers to any haplogroup which is not descended from the haplogroup BT; in other words, it is defined by the absence of the defining mutation of that group (M91). By this definition, haplogroup A includes all mutations that took place between the Y-chromosomal most recent common ancestor (estimated at some 270 kya) and the mutation defining haplogroup BT (estimated at some 140–150 kya),[8] including any extant subclades that may yet to be discovered.

Bearers of haplogroup A (i.e. absence of the defining mutation of haplogroup BT) have been found in Southern Africa's hunter-gatherer inhabited areas, especially among the San people. In addition, the most basal mitochondrial DNA L0 lineages are also largely restricted to the San. However, the A lineages of Southern Africa are sub-clades of A lineages found in other parts of Africa, suggesting that A sub-haplogroups arrived in Southern Africa from elsewhere.[9]

The two most basal lineages of haplogroup A, A0 and A1 (prior to the announcement of the discovery of haplogroup A00 in 2013), have been detected in West Africa, Northwest Africa and Central Africa. Cruciani et al. (2011) suggest that these lineages may have emerged somewhere in between Central and Northwest Africa.[10] Scozzari et al. (2012) also supported "the hypothesis of an origin in the north-western quadrant of the African continent for the A1b [ i.e. A0 ] haplogroup".[11]

Haplogroup A1b1b2 has been found among ancient fossils excavated at Balito Bay in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, which have been dated to around 2149-1831 BP (2/2; 100%).[12]

Distribution

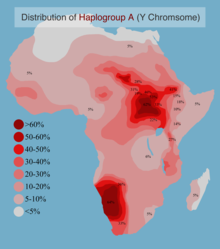

editBy definition of haplogroup A as "non-BT", it is almost completely restricted to Africa, though a very small handful of bearers have been reported in Europe and Western Asia.

The clade achieves its highest modern frequencies in the Bushmen hunter-gatherer populations of Southern Africa, followed closely by many Nilotic groups in Eastern Africa. However, haplogroup A's oldest sub-clades are exclusively found in Central-Northwest Africa, where it (and by extension the patrilinear ancestor of modern humans) is believed to have originated. Estimates of its time depth have varied greatly, at either close to 190 kya or close to 140 kya in separate 2013 studies,[10][13] and with the inclusion of the previously unknown "A00" haplogroup to about 270 kya in 2015 studies.[14][15]

The clade has also been observed at notable frequencies in certain populations in Ethiopia, as well as some Pygmy groups in Central Africa, and less commonly Niger–Congo speakers, who largely belong to the E1b1a clade. Haplogroup E in general is believed to have originated in Northeast Africa,[16] and was later introduced to West Africa from where it spread around 5,000 years ago to Central, Southern and Southeastern Africa with the Bantu expansion.[17][18] According to Wood et al. (2005) and Rosa et al. (2007), such relatively recent population movements from West Africa changed the pre-existing population Y chromosomal diversity in Central, Southern and Southeastern Africa, replacing the previous haplogroups in these areas with the now dominant E1b1a lineages. Traces of ancestral inhabitants, however, can be observed today in these regions via the presence of the Y DNA haplogroups A-M91 and B-M60 that are common in certain relict populations, such as the Mbuti Pygmies and the Khoisan.[19][20][21]

| Africa | ||

| Study population | Freq. (in %) | |

| [20] | Tsumkwe San (Namibia) | 66% |

| [20] | Nama (Namibia) | 64 |

| [22] | Dinka (Sudan) | 62 |

| [22] | Shilluk (Sudan) | 53 |

| [22] | Nuba (Sudan) | 46 |

| [23] | Khoisan | 44 |

| [24][25] | Ethiopian Jews | 41 |

| [20][24] | !Kung/Sekele | ~40 |

| [22] | Borgu (Sudan) | 35 |

| [22] | Nuer (Sudan) | 33 |

| [22] | Fur (Sudan) | 31 |

| [20] | Maasai (Kenya) | 27 |

| [26] | Nara (Eritrea) | 20 |

| [22] | Masalit (Sudan) | 19 |

| [27] | Ethiopians | 14 |

| [20] | Bantu (Kenya) | 14 |

| [22] | Mandara (Cameroon) | 14 |

| [24] | Hausa (Sudan) | 13 |

| [24] | Khwe (South Africa) | 12 |

| [20] | Fulbe (Cameroon) | 12 |

| [28] | Dama (Namibia) | 11 |

| [26] | Oromo (Ethiopia) | 10 |

| [20] | Kunama (Eritrea) | 10 |

| [27] | South Semitic (Ethiopia) | 10 |

| Arabs (Egypt) | 3 | |

In a composite sample of 3551 African men, Haplogroup A had a frequency of 5.4%.[29] The highest frequencies of haplogroup A have been reported among the Khoisan of Southern Africa, Beta Israel, and Nilo-Saharans from Sudan.

North America

edit1 African American Male out of Lacrosse, WI USA, Moses, Ramon, A00, A00-AF8

Africa

editNorth Africa

editIn North Africa, haplogroup A is largely absent. Its subclade A1 has been observed at trace frequencies among Moroccans.

Upper Nile

editHaplogroup A3b2-M13 is common among the Southern Sudanese (53%),[22] especially the Dinka Sudanese (61.5%).[30] Haplogroup A3b2-M13 also has been observed in another sample of a South Sudanese population at a frequency of 45% (18/40), including 1/40 A3b2a-M171.[23]

Further downstream around the Nile valley, the subclade A3b2 has also been observed at very low frequencies in a sample of Egyptian males (3%).

West Africa

editEight male individuals from Guinea Bissau, two male individuals from Niger, one male individual from Mali, and one male individual from Cabo Verde carried haplogroup A1a.[31]

Central Africa

editHaplogroup A3b2-M13 has been observed in populations of northern Cameroon (2/9 = 22% Tupuri,[20] 4/28 = 14% Mandara,[20] 2/17 = 12% Fulbe[24]) and eastern DRC (2/9 = 22% Alur,[20] 1/18 = 6% Hema,[20] 1/47 = 2% Mbuti[20]).

Haplogroup A-M91(xA1a-M31, A2-M6/M14/P3/P4, A3-M32) has been observed in the Bakola people of southern Cameroon (3/33 = 9%).[20]

Without testing for any subclade, haplogroup A Y-DNA has been observed in samples of several populations of Gabon, including 9% (3/33) of a sample of Baka, 3% (1/36) of a sample of Ndumu, 2% (1/46) of a sample of Duma, 2% (1/57) of a sample of Nzebi, and 2% (1/60) of a sample of Tsogo.[18]

East Africa

editAfrican Great Lakes

editBantus in Kenya (14%, Luis et al. 2004) and Iraqw in Tanzania (3/43 = 7.0% (Luis et al. 2004) to 1/6 = 17% (Knight et al. 2003)).

Horn of Africa

editHaplogroup A is found at low to moderate frequencies in the Horn of Africa. The clade is observed at highest frequencies among the 41% of a sample of the Beta Israel, occurring among 41% of one sample from this population (Cruciani et al. 2002). Elsewhere in the region, haplogroup A has been reported in 14.6% (7/48) of an Amhara sample,[28] 10.3% (8/78) of an Oromo sample,[28] and 13.6% (12/88) of another sample from Ethiopia.[23]

Southern Africa

editOne 2005 study has found haplogroup A in samples of various Khoisan-speaking tribes with frequency ranging from 10% to 70%.[20] This particular haplogroup was not found in a sample of the Hadzabe from Tanzania,[citation needed] a population sometimes proposed as a remnant of a Late Stone Age Khoisanid population.

Asia

editIn Asia, haplogroup A has been observed at low frequencies in Asia Minor and the Middle East among Aegean Turks, Palestinians, Jordanians, Yemenites.[32]

Europe

editA3a2 (A-M13; formerly A3b2), has been observed at very low frequencies in some Mediterranean islands. Without testing for any subclade, haplogroup A has been found in a sample of Greeks from Mitilini on the Aegean island of Lesvos[32] and in samples of Portuguese from southern Portugal, central Portugal, and Madeira.[33] The authors of one study have reported finding what appears to be haplogroup A in 3.1% (2/65) of a sample of Cypriots,[34] though they have not definitively excluded the possibility that either of these individuals may belong to a rare subclade of haplogroup BT, including haplogroup CT.

Subclades

editA00 (A00-AF6)

editMendez et al. (2013) announced the discovery of a previously unknown haplogroup, for which they proposed the designator "A00".[35] "Genotyping of a DNA sample that was submitted to a commercial genetic-testing facility demonstrated that the Y chromosome of this African American individual carried the ancestral state of all known Y chromosome SNPs. To further characterize this lineage, which we dubbed A00,[36] for proposed nomenclature)"; "We have renamed the basal branch in Cruciani et al. [2011] as A0 (previously A1b) and refer to the presently reported lineage as A00. For deep branches discovered in the future, we suggest continuing the nomenclature A000, and so on." It has an estimated age of around 275 kya,[14][15] so is roughly contemporary with the known appearance of earliest known anatomically modern humans, such as Jebel Irhoud.[37] A00 is also sometimes known as "Perry's Y-chromosome" (or simply "Perry's Y"). This previously unknown haplogroup was discovered in 2012 in the Y chromosome of an African-American man who had submitted his DNA for commercial genealogical analysis.[38] The subsequent discovery of other males belonging to A00 led to the reclassification of Perry's Y as A00a (A-L1149).

Researchers later found A00 was possessed by 11 Mbo males of Western Cameroon (Bantu) (out of a sample of 174 (6.32%).[39] Subsequent research suggested that the overall rate of A00 was even higher among the Mbo, i.e. 9.3% (8 of 86) were later found to fall within A00b (A-A4987).

Further research in 2015 indicates that the modern population with the highest concentration of A00 is the Bangwa (or Nweh), a Yemba-speaking group of Cameroon (Grassfields Bantu): 27 of 67 (40.3%) samples were positive for A00a (L1149). One Bangwa individual did not fit into either A00a or A00b.[40]

Geneticists sequenced genome-wide DNA data from four people buried at the site of Shum Laka in Cameroon between 8000–3000 years ago, who were most genetically similar to Mbuti pygmies. One individual carried the deeply divergent Y chromosome haplogroup A00.[41]

A0 (A-V148)

editThe haplogroup names "A-V148" and "A-CTS2809/L991" refer to the exact same haplogroup.

A0 is found only in Bakola Pygmies (South Cameroon) at 8.3% and Berbers from Algeria at 1.5%.[10] Also found in Ghana.[11][failed verification]

A1a (A-M31)

editThe subclade A1a (M31) has been found in approximately 2.8% (8/282) of a pool of seven samples of various ethnic groups in Guinea-Bissau, especially among the Papel-Manjaco-Mancanha (5/64 = 7.8%).[19] In an earlier study published in 2003, Gonçalves et al. have reported finding A1a-M31 in 5.1% (14/276) of a sample from Guinea-Bissau and in 0.5% (1/201) of a pair of samples from Cabo Verde.[42] The authors of another study have reported finding haplogroup A1a-M31 in 5% (2/39) of a sample of Mandinka from Senegambia and 2% (1/55) of a sample of Dogon from Mali.[20] Haplogroup A1a-M31 also has been found in 3% (2/64) of a sample of Berbers from Morocco[24] and 2.3% (1/44) of a sample of unspecified ethnic affiliation from Mali.[23]

In 2007, seven men from Yorkshire, England sharing the unusual surname Revis were identified as being from the A1a (M31) subclade. It was discovered that these men had a common male-line ancestor from the 18th century, but no previous information about African ancestry was known.[29]

In 2023, Lacrosse, WI, 1 Male, A1a-M31, Moses, Ramon.[43]

A1b1a1a (A-M6)

editThe subclade A1b1a1a (M6; formerly A2 and A1b1a1a-M6) is typically found among Khoisan peoples. The authors of one study have reported finding haplogroup A-M6(xA-P28) in 28% (8/29) of a sample of Tsumkwe San and 16% (5/32) of a sample of !Kung/Sekele, and haplogroup A2b-P28 in 17% (5/29) of a sample of Tsumkwe San, 9% (3/32) of a sample of !Kung/Sekele, 9% (1/11) of a sample of Nama, and 6% (1/18) of a sample of Dama.[20] The authors of another study have reported finding haplogroup A2 in 15.4% (6/39) of a sample of Khoisan males, including 5/39 A2-M6/M14/M23/M29/M49/M71/M135/M141(xA2a-M114) and 1/39 A2a-M114.[23]

A1b1b (A-M32)

editThe clade A1b1b (M32; formerly A3) contains the most populous branches of haplogroup A and is mainly found in Eastern Africa and Southern Africa.

A1b1b1 (A-M28)

editThe subclade (appropriately considered as a distinct haplogroup) A1b1b1 (M28; formerly A3a) has only been rarely observed in the Horn of Africa. In 5% (1/20) of a mixed sample of speakers of South Semitic languages from Ethiopia,[20] 1.1% (1/88) of a sample of Ethiopians,[23] and 0.5% (1/201) in Somalis.[16] it has also been observed in Eastern, Central and Southern of Arabia. Current results, according to FTDNA, suggest that some branches such as A-V1127 originated in Arabia. Additionally, as suggested by experts as seen in TMRCA in Yfull tree, this haplogroup must have undergone a bottleneck time when people who represent this haplogroup suffered some sort of extinction and sharply decreased in number. Noteworthy, non semitic speakers don't have this haplogroup neither the koi-san or the nilots or the Cushites.

A1b1b2a (A-M51)

editThe subclade A1b1b2a (M51; formerly A3b1) occurs most frequently among Khoisan peoples (6/11 = 55% Nama,[20] 11/39 = 28% Khoisan,[23] 7/32 = 22% !Kung/Sekele,[20] 6/29 = 21% Tsumkwe San,[20] 1/18 = 6% Dama[20]). However, it also has been found with lower frequency among Bantu peoples of Southern Africa, including 2/28 = 7% Sotho–Tswana,[20] 3/53 = 6% non-Khoisan Southern Africans,[23] 4/80 = 5% Xhosa,[20] and 1/29 = 3% Zulu.[20]

A1b1b2b (A-M13)

editThe subclade A1b1b2b (M13; formerly A3b2) is primarily distributed among Nilotic populations in East Africa and northern Cameroon. It is different from the A subclades that are found in the Khoisan samples and only remotely related to them (it is actually only one of many subclades within haplogroup A). This finding suggests an ancient divergence.

In Sudan, haplogroup A-M13 has been found in 28/53 = 52.8% of Southern Sudanese, 13/28 = 46.4% of the Nuba of central Sudan, 25/90 = 27.8% of Western Sudanese, 4/32 = 12.5% of local Hausa people, and 5/216 = 2.3% of Northern Sudanese.[44]

In Ethiopia, one study has reported finding haplogroup A-M13 in 14.6% (7/48) of a sample of Amhara and 10.3% (8/78) of a sample of Oromo.[28] Another study has reported finding haplogroup A3b2b-M118 in 6.8% (6/88) and haplogroup A3b2*-M13(xA3b2a-M171, A3b2b-M118) in 5.7% (5/88) of a mixed sample of Ethiopians, amounting to a total of 12.5% (11/88) A3b2-M13.[23]

Haplogroup A-M13 also has been observed occasionally outside of Central and Eastern Africa, as in the Aegean Region of Turkey (2/30 = 6.7%[45]), Yemenite Jews (1/20 = 5%[25]), Egypt (4/147 = 2.7%,[27] 3/92 = 3.3%[20]), Palestinian Arabs (2/143 = 1.4%[46]), Sardinia (1/77 = 1.3%,[47] 1/22 = 4.5%[23]), the capital of Jordan, Amman (1/101=1%[48]), and Oman (1/121 = 0.8%[27]).

Haplogroup A-M13 has been found among three Neolithic period fossils excavated from the Kadruka site in Sudan.[49]

Haplogroup A-M13 was also found in a male victim of the Mt. Vesuvius eruption in Pompeii.[50]

Phylogenetics

editPhylogenetic history

editPrior to 2002, there were in academic literature at least seven naming systems for the Y-Chromosome Phylogenetic tree. This led to considerable confusion. In 2002, the major research groups came together and formed the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC). They published a joint paper that created a single new tree that all agreed to use. Later, a group of citizen scientists with an interest in population genetics and genetic genealogy formed a working group to create an amateur tree aiming at being above all timely. The table below brings together all of these works at the point of the landmark 2002 YCC Tree. This allows a researcher reviewing older published literature to quickly move between nomenclatures.

Initial sequencing of the human Y-chromosome had suggested that first split in the Y-Chromosome family tree occurred with the mutations that separated Haplogroup BT from Y-chromosomal Adam and haplogroup A more broadly.[51] Subsequently, many intervening splits between Y-chromosomal Adam and BT, also became known.

A major shift in the understanding of the Y-DNA tree came with the publication of (Cruciani 2011). While the SNP marker M91 had been regarded as a key to identifying haplogroup BT, it was realised that the region surrounding M91 was a mutational hotspot, which is prone to recurrent back-mutations. Moreover, the 8T stretch of Haplogroup A represented the ancestral state of M91, and the 9T of haplogroup BT a derived state, which arose following the insertion of 1T. This explained why subclades A1b and A1a, the deepest branches of Haplogroup A, both possessed the 8T stretch. Similarly, the P97 marker, which was also used to identify haplogroup A, possessed the ancestral state in haplogroup A, but a derived state in haplogroup BT.[10] Ultimately the tendency of M91 to back-mutate and (hence) its unreliability, led to M91 being discarded as a defining SNP by ISOGG in 2016.[52] Conversely, P97 has been retained as a defining marker of Haplogroup BT.

| YCC 2002/2008 (Shorthand) | (α) | (β) | (γ) | (δ) | (ε) | (ζ) | (η) | YCC 2002 (Longhand) | YCC 2005 (Longhand) | YCC 2008 (Longhand) | YCC 2010r (Longhand) | ISOGG 2006 | ISOGG 2007 | ISOGG 2008 | ISOGG 2009 | ISOGG 2010 | ISOGG 2011 | ISOGG 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-M31 | 7 | I | 1A | 1 | – | H1 | A | A1 | A1 | A1 | A1a | A1 | A1 | A1a | A1a | A1a | A1a | A1a |

| A-M6 | 27 | I | 2 | 3 | – | H1 | A | A2* | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A2 | A1b1a1a |

| A-M114 | 27 | I | 2 | 3 | – | H1 | A | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A2a | A1b1a1a1a |

| A-P28 | 27 | I | 2 | 4 | – | H1 | A | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A2b | A1b1a1a1b |

| A-M32 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | A3 | A3 | A3 | A3 | A3 | A3 | A3 | A3 | A3 | A1b1b |

| A-M28 | 7 | I | 1A | 1 | – | H1 | A | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A3a | A1b1b1 |

| A-M51 | 7 | I | 1A | 1 | – | H1 | A | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A3b1 | A1b1b2a |

| A-M13 | 7 | I | 1A | 2 | Eu1 | H1 | A | A3b2* | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A3b2 | A1b1b2b |

| A-M171 | 7 | I | 1A | 2 | Eu1 | H1 | A | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | A3b2a | removed |

| A-M118 | 7 | I | 1A | 2 | Eu1 | H1 | A | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A3b2b | A1b1b2b1 |

The following research teams per their publications were represented in the creation of the YCC Tree.

Phylogenetic trees

editThe above phylogenetic tree is based on the ISOGG,[17] YCC,[53] and subsequent published research.

Y-chromosomal Adam

A00 (AF6/L1284)

- A00a (L1149, FGC25576, FGC26292, FGC26293, FGC27741)

- A00b (A4987/YP3666, A4981, A4982/YP2683, A4984/YP2995, A4985/YP3292, A4986, A4988/YP3731)

A0-T (L1085)

- A0 (CTS2809/L991) formerly A1b

- A1 (P305) formerly A1a-T, A0 and A1b

- A1a (M31)

- A1b (P108) formerly A2-T

- A1b1 (L419/PF712)

- A1b1a (L602, V50, V82, V198, V224)

- A1b1a1 (M14) formerly A2

- A1b1a1a (M6)

- A1b1a1a1 (P28) formerly A1b1a1a1b and A2b

- A1b1a1a (M6)

- A1b1a1 (M14) formerly A2

- A1b1b (M32) formerly A3

- A1b1b1 (M28) formerly A3a

- A1b1b2 (L427)

- A1b1b2a (M51/Page42) formerly A3b1

- A1b1b2a1 (P291)

- A1b1b2b (M13/PF1374) formerly A3b2

- A1b1b2b1 (M118)

- A1b1b2a (M51/Page42) formerly A3b1

- A1b1a (L602, V50, V82, V198, V224)

- BT (M91)

- A1b1 (L419/PF712)

See also

edit- Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup

- Y-DNA haplogroups in populations of Sub-Saharan Africa

- Y-DNA haplogroups by ethnic group

- Y-DNA A subclades

References

edit- ^ equivalent to an estimate of the age of the human Y-MRCA (see there); including the A00 lineage, Karmin et al. (2015) and Trombetta et al. (2015) estimate ages of 254,000 and 291,000 ybp, respectively.

- ^ Karmin; et al. (2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–66. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088. "we date the Y-chromosomal most recent common ancestor (MRCA) in Africa at 254 (95% CI 192–307) kya and detect a cluster of major non-African founder haplogroups in a narrow time interval at 47–52 kya, consistent with a rapid initial colonization model of Eurasia and Oceania after the out-of-Africa bottleneck. In contrast to demographic reconstructions based on mtDNA, we infer a second strong bottleneck in Y-chromosome lineages dating to the last 10 ky. We hypothesize that this bottleneck is caused by cultural changes affecting variance of reproductive success among males."

- ^ Mendez, L.; et al. (2016). "The Divergence of Neandertal and Modern Human Y Chromosomes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 98 (4): 728–34. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.023. PMC 4833433. PMID 27058445.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Ribot, Isabelle; Mallick, Swapan; Rohland, Nadin; Olalde, Iñigo; Adamski, Nicole; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Lawson, Ann Marie; López, Saioa; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Stewardson, Kristin; Asombang, Raymond Neba’ane; Bocherens, Hervé; Bradman, Neil; Culleton, Brendan J.; Cornelissen, Els; Crevecoeur, Isabelle; de Maret, Pierre; Fomine, Forka Leypey Mathew; Lavachery, Philippe; Mindzie, Christophe Mbida; Orban, Rosine; Sawchuk, Elizabeth; Semal, Patrick; Thomas, Mark G.; Van Neer, Wim; Veeramah, Krishna R.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Patterson, Nick; Hellenthal, Garrett; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; MacEachern, Scott; Prendergast, Mary E.; Reich, David (30 January 2020). "Ancient West African foragers in the context of African population history". Nature. 577 (7792): 665–670. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..665L. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1929-1. PMC 8386425. PMID 31969706.

- ^ Trombetta, Beniamino; d'Atanasio, Eugenia; Massaia, Andrea; Myres, Natalie M.; Scozzari, Rosaria; Cruciani, Fulvio; Novelletto, Andrea (2015). "Regional Differences in the Accumulation of SNPs on the Male-Specific Portion of the Human Y Chromosome Replicate Autosomal Patterns: Implications for Genetic Dating". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0134646. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1034646T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134646. PMC 4520482. PMID 26226630.

- ^ "A00 YTree".

- ^ According to Cruciani et al. 2011, the most basal lineages have been detected in West, Northwest and Central Africa, suggesting plausibility for the Y-MRCA living in the general region of North-Central Africa". In a sample of 2204 African Y-chromosomes, 8 chromosomes belonged to either haplogroup A1b or A1a. Haplogroup A1a was identified in two Moroccan Berbers, one Fulbe and one Tuareg people from Niger. Haplogroup A1b was identified in three Bakola pygmies from Southern Cameroon and one Algerian Berber. Cruciani, Fulvio; Trombetta, Beniamino; Massaia, Andrea; Destro-Bisol, Giovanni; Sellitto, Daniele; Scozzari, Rosaria (2011). "A Revised Root for the Human Y Chromosomal Phylogenetic Tree: The Origin of Patrilineal Diversity in Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (6): 814–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.002. PMC 3113241. PMID 21601174. Scozzari et al. (2012) agreed with a plausible placement in "the north-western quadrant of the African continent" for the emergence of the A1b haplogroup: "the hypothesis of an origin in the north-western quadrant of the African continent for the A1b haplogroup, and, together with recent findings of ancient Y-lineages in central-western Africa, provide new evidence regarding the geographical origin of human MSY diversity". Scozzari R; Massaia A; D'Atanasio E; Myres NM; Perego UA; et al. (2012). Caramelli, David (ed.). "Molecular Dissection of the Basal Clades in the Human Y Chromosome Phylogenetic Tree". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e49170. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749170S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049170. PMC 3492319. PMID 23145109.

- ^ Kamin M, Saag L, Vincente M, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ Batini C, Ferri G, Destro-Bisol G, et al. (September 2011). "Signatures of the preagricultural peopling processes in sub-Saharan Africa as revealed by the phylogeography of early Y chromosome lineages". Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 (9): 2603–13. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr089. hdl:10400.13/4486. PMID 21478374.

- ^ a b c d Cruciani F, Trombetta B, Massaia A, Destro-Bisol G, Sellitto D, Scozzari R (June 2011). "A revised root for the human Y chromosomal phylogenetic tree: the origin of patrilineal diversity in Africa". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88 (6): 814–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.002. PMC 3113241. PMID 21601174.

- ^ a b Scozzari R, Massaia A, D'Atanasio E, et al. (2012). "Molecular dissection of the basal clades in the human Y chromosome phylogenetic tree". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e49170. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...749170S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049170. PMC 3492319. PMID 23145109.

- ^ Carina M. Schlebusch; et al. (28 September 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

- ^ Francalacci P, Morelli L, Angius A, Berutti R, Reinier F, Atzeni R, Pilu R, Busonero F, Maschio A, Zara I, Sanna D, Useli A, Urru MF, Marcelli M, Cusano R, Oppo M, Zoledziewska M, Pitzalis M, Deidda F, Porcu E, Poddie F, Kang HM, Lyons R, Tarrier B, Gresham JB, Li B, Tofanelli S, Alonso S, Dei M, Lai S, Mulas A, Whalen MB, Uzzau S, Jones C, Schlessinger D, Abecasis GR, Sanna S, Sidore C, Cucca F (2013). "Low-pass DNA sequencing of 1200 Sardinians reconstructs European Y-chromosome phylogeny". Science. 341 (6145): 565–569. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..565F. doi:10.1126/science.1237947. PMC 5500864. PMID 23908240.Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, Snyder M, Quintana-Murci L, Kidd JM, Underhill PA, Bustamante CD (2013). "Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females". Science. 341 (6145): 562–565. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..562P. doi:10.1126/science.1237619. PMC 4032117. PMID 23908239. Cruciani et al. (2011) estimated 142 kya.

- ^ a b "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–66. 2015. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- ^ a b "Regional Differences in the Accumulation of SNPs on the Male-Specific Portion of the Human Y Chromosome Replicate Autosomal Patterns: Implications for Genetic Dating". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0134646. 2015. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1034646T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0134646. PMC 4520482. PMID 26226630.

- ^ a b Abu-Amero KK, Hellani A, González AM, Larruga JM, Cabrera VM, Underhill PA (2009). "Saudi Arabian Y-Chromosome diversity and its relationship with nearby regions". BMC Genet. 10: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-10-59. PMC 2759955. PMID 19772609.

- ^ a b International Society of Genetic Genealogy. "Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree".

- ^ a b Berniell-Lee G, Calafell F, Bosch E, et al. (July 2009). "Genetic and demographic implications of the Bantu expansion: insights from human paternal lineages". Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 (7): 1581–9. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp069. PMID 19369595.

- ^ a b Rosa A, Ornelas C, Jobling MA, Brehm A, Villems R (2007). "Y-chromosomal diversity in the population of Guinea-Bissau: a multiethnic perspective". BMC Evol. Biol. 7 (1): 124. Bibcode:2007BMCEE...7..124R. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-124. PMC 1976131. PMID 17662131.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Wood ET, Stover DA, Ehret C, et al. (July 2005). "Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome and mtDNA variation in Africa: evidence for sex-biased demographic processes". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 13 (7): 867–76. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201408. PMID 15856073.

- ^ Underhill PA, Passarino G, Lin AA, et al. (January 2001). "The phylogeography of Y chromosome binary haplotypes and the origins of modern human populations". Ann. Hum. Genet. 65 (Pt 1): 43–62. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6510043.x. PMID 11415522. S2CID 9441236.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 28/53 (Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk), Hassan HY, Underhill PA, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Ibrahim ME (November 2008). "Y-chromosome variation among Sudanese: restricted gene flow, concordance with language, geography, and history". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 137 (3): 316–23. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20876. PMID 18618658.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Underhill PA, Shen P, Lin AA, et al. (November 2000). "Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations". Nat. Genet. 26 (3): 358–61. doi:10.1038/81685. PMID 11062480. S2CID 12893406.

- ^ a b c d e f Cruciani F, Santolamazza P, Shen P, et al. (May 2002). "A back migration from Asia to sub-Saharan Africa is supported by high-resolution analysis of human Y-chromosome haplotypes". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70 (5): 1197–214. doi:10.1086/340257. PMC 447595. PMID 11910562.

- ^ a b Shen P, Lavi T, Kivisild T, et al. (September 2004). "Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence variation". Hum. Mutat. 24 (3): 248–60. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. PMID 15300852. S2CID 1571356.

- ^ a b Cruciani F, Trombetta B, Sellitto D, et al. (July 2010). "Human Y chromosome haplogroup R-V88: a paternal genetic record of early mid Holocene trans-Saharan connections and the spread of Chadic languages". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18 (7): 800–7. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.231. PMC 2987365. PMID 20051990.

- ^ a b c d Luis JR, Rowold DJ, Regueiro M, et al. (March 2004). "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: evidence for bidirectional corridors of human migrations". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (3): 532–44. doi:10.1086/382286. PMC 1182266. PMID 14973781.

- ^ a b c d Semino O, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS, Falaschi F, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA (January 2002). "Ethiopians and Khoisan share the deepest clades of the human Y-chromosome phylogeny". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70 (1): 265–8. doi:10.1086/338306. PMC 384897. PMID 11719903.

- ^ a b King TE, Parkin EJ, Swinfield G, et al. (March 2007). "Africans in Yorkshire? The deepest-rooting clade of the Y phylogeny within an English genealogy". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 15 (3): 288–93. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201771. PMC 2590664. PMID 17245408.

News article: "Yorkshire clan linked to Africa". BBC News. 2007-01-24. Retrieved 2007-01-27. - ^ 16/26, Hassan et al. 2008

- ^ Batini, Chiara; et al. (September 2011). "Supplementary Data: Signatures of the Preagricultural Peopling Processes in Sub-Saharan Africa as Revealed by the Phylogeography of Early Y Chromosome Lineages". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (9): 2603–2613. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr089. hdl:10400.13/4486. ISSN 0737-4038. OCLC 748733133. PMID 21478374. S2CID 11190055.

- ^ a b Di Giacomo F, Luca F, Anagnou N, et al. (September 2003). "Clinal patterns of human Y chromosomal diversity in continental Italy and Greece are dominated by drift and founder effects". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 28 (3): 387–95. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00016-2. PMID 12927125.

- ^ Gonçalves R, Freitas A, Branco M, et al. (July 2005). "Y-chromosome lineages from Portugal, Madeira and Açores record elements of Sephardim and Berber ancestry". Ann. Hum. Genet. 69 (Pt 4): 443–54. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x. hdl:10400.13/3018. PMID 15996172. S2CID 3229760.

- ^ Capelli C, Redhead N, Romano V, et al. (March 2006). "Population structure in the Mediterranean basin: a Y chromosome perspective". Ann. Hum. Genet. 70 (Pt 2): 207–25. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00224.x. hdl:2108/37090. PMID 16626331. S2CID 25536759.

- ^ Mendez, Fernando L.; Krahn, Thomas; Schrack, Bonnie; Krahn, Astrid-Maria; Veeramah, Krishna R.; Woerner, August E.; Fomine, Forka Leypey Mathew; Bradman, Neil; Thomas, Mark G.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Hammer, Michael F. (March 2013). "An African American Paternal Lineage Adds an Extremely Ancient Root to the Human Y Chromosome Phylogenetic Tree". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 92 (3): 454–459. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.002. PMC 3591855. PMID 23453668.

- ^ Mendez, Fernando L.; Krahn, Thomas; Schrack, Bonnie; Krahn, Astrid-Maria; Veeramah, Krishna R.; Woerner, August E.; Fomine, Forka Leypey Mathew; Bradman, Neil; Thomas, Mark G.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Hammer, Michael F. (March 2013). "An African American Paternal Lineage Adds an Extremely Ancient Root to the Human Y Chromosome Phylogenetic Tree". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 92 (3): 454–459. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.002. PMC 3591855. PMID 23453668.

- ^ At first, via Mendez et al. (2013), this was announced as "extremely ancient" (95% confidence interval 237–581 kya for the age of the Y-MRCA including the lineage of this postulated haplogroup).

- ^ Albert Perry, a slave born in the United States between ca. 1819–1827, lived in York County, South Carolina. See FamilyTreeDNA, Haplogroup A chart

- ^ Mendez et al. (2013), p. 455. Quote: "Upon searching a large pan-African database consisting of 5,648 samples from ten countries [...] we identified 11 Y chromosomes that were invariant and identical to the A00 chromosome at five of the six Y-STRs (2 of the 11 chromosomes carried DYS19-16, whereas the others carried DYS19-15). These 11 chromosomes were all found in a sample of 174 (~6.3%) Mbo individuals from western Cameroon (Figure 2). Seven of these Mbo chromosomes were available for further testing, and the genotypes were found to be identical at 37 of 39 SNPs known to be derived on the A00 chromosome (i.e., two of these genotyped SNPs were ancestral in the Mbo samples)".

- ^ Which of Cameroon's peoples have members of haplogroup A00? // experiment.com update of funded research (Schrack/Fomine Forka) available online[self-published source?] Quotes: We can now clearly see that with 40% A00, the Bangwa represent the epicentre of A00 in this region, and very possibly in the world. As I shared in the last Lab Note, we found that so far there are two main subgroups of A00, defined by different Y-SNP mutations, which, naturally, divide along ethnic lines: A00a among the Bangwa, and A00b among the Mbo. We also found the one Bangwa sample which didn't belong to either subgroup.".

- ^ Lipson Mark et al. Ancient Human DNA from Shum Laka (Cameroon) in the Context of African Population History // SAA 2019

- ^ Gonçalves R, Rosa A, Freitas A, et al. (November 2003). "Y-chromosome lineages in Cabo Verde Islands witness the diverse geographic origin of its first male settlers". Hum. Genet. 113 (6): 467–72. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1007-4. hdl:10400.13/3047. PMID 12942365. S2CID 63381583.

- ^ 23andme raw data

- ^ Hisham Y. Hassan et al. (2008). "Southern Sudanese" includes 26 Dinka, 15 Shilluk, and 12 Nuer. "Western Sudanese" includes 26 Borgu, 32 Masalit, and 32 Fur. "Northern Sudanese" includes 39 Nubians, 42 Beja, 33 Copts, 50 Gaalien, 28 Meseria, and 24 Arakien.

- ^ Cinnioğlu C, King R, Kivisild T; et al. (January 2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Hum. Genet. 114 (2): 127–48. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639. S2CID 10763736.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nebel A, Filon D, Brinkmann B, Majumder PP, Faerman M, Oppenheim A (November 2001). "The Y chromosome pool of Jews as part of the genetic landscape of the Middle East". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69 (5): 1095–112. doi:10.1086/324070. PMC 1274378. PMID 11573163.

- ^ Semino O, Passarino G, Oefner PJ, et al. (November 2000). "The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–9. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- ^ Flores C, Maca-Meyer N, Larruga JM, Cabrera VM, Karadsheh N, Gonzalez AM (2005). "Isolates in a corridor of migrations: a high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variation in Jordan". J. Hum. Genet. 50 (9): 435–41. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0274-4. PMID 16142507.

- ^ Yousif, Hisham; Eltayeb, Muntaser (July 2009). Genetic Patterns of Y-chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Variation, with Implications to the Peopling of the Sudan (Thesis). Archived from the original on 2022-08-25. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- ^ Scorrano, Gabriele; Viva, Serena; Pinotti, Thomaz; Fabbri, Pier Francesco; Rickards, Olga; Macciardi, Fabio (26 May 2022). "Bioarchaeological and palaeogenomic portrait of two Pompeians that died during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 6468. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12.6468S. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-10899-1. PMC 9135728. PMID 35618734.

- ^ Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Meilerman MB, Underhill PA, Zegura SL, Hammer MF (2008). "New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree". Genome Research. 18 (5): 830–8. doi:10.1101/gr.7172008. PMC 2336805. PMID 18385274.

- ^ ISOGG, 2016, Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree 2016. (Access: 29 August 2017.)

- ^ Krahn, Thomas. "YCC Tree". FTDNA. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

Bibliography

edit- Mendez FL, Krahn T, Schrack B, et al. (March 2013). "An African American paternal lineage adds an extremely ancient root to the human Y chromosome phylogenetic tree". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92 (3): 454–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.02.002. PMC 3591855. PMID 23453668. as PDF Archived 2019-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Y-Haplogroup A Phylogenetic Tree". March 2013. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2013. (chart highlighting new branches added to the A phylotree in March 2013)

Sources for conversion tables

edit- Capelli, Cristian; Wilson, James F.; Richards, Martin; Stumpf, Michael P.H.; et al. (February 2001). "A Predominantly Indigenous Paternal Heritage for the Austronesian-Speaking Peoples of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 432–443. doi:10.1086/318205. PMC 1235276. PMID 11170891.

- Hammer, Michael F.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Redd, Alan J.; Jarjanazi, Hamdi; et al. (1 July 2001). "Hierarchical Patterns of Global Human Y-Chromosome Diversity". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (7): 1189–1203. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003906. PMID 11420360.

- Jobling, Mark A.; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2000), "New uses for new haplotypes", Trends in Genetics, 16 (8): 356–62, doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02057-6, PMID 10904265

- Kaladjieva, Luba; Calafell, Francesc; Jobling, Mark A; Angelicheva, Dora; et al. (February 2001). "Patterns of inter- and intra-group genetic diversity in the Vlax Roma as revealed by Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA lineages". European Journal of Human Genetics. 9 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200597. PMID 11313742.

- Karafet, Tatiana; Xu, Liping; Du, Ruofu; Wang, William; et al. (September 2001). "Paternal Population History of East Asia: Sources, Patterns, and Microevolutionary Processes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (3): 615–628. doi:10.1086/323299. PMC 1235490. PMID 11481588.

- Semino, O.; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; et al. (2000), "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective", Science, 290 (5494): 1155–9, Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S, doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155, PMID 11073453

- Su, Bing; Xiao, Junhua; Underhill, Peter; Deka, Ranjan; et al. (December 1999). "Y-Chromosome Evidence for a Northward Migration of Modern Humans into Eastern Asia during the Last Ice Age". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 65 (6): 1718–1724. doi:10.1086/302680. PMC 1288383. PMID 10577926.

- Underhill, Peter A.; Shen, Peidong; Lin, Alice A.; Jin, Li; et al. (November 2000). "Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations". Nature Genetics. 26 (3): 358–361. doi:10.1038/81685. PMID 11062480. S2CID 12893406.