Hypoglycemia (American English), also spelled hypoglycaemia or hypoglycæmia (British English), sometimes called low blood sugar, is a fall in blood sugar to levels below normal, typically below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).[1][3] Whipple's triad is used to properly identify hypoglycemic episodes.[2] It is defined as blood glucose below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), symptoms associated with hypoglycemia, and resolution of symptoms when blood sugar returns to normal.[1] Hypoglycemia may result in headache, tiredness, clumsiness, trouble talking, confusion, fast heart rate, sweating, shakiness, nervousness, hunger, loss of consciousness, seizures, or death.[1][3][2] Symptoms typically come on quickly.[1]

| Hypoglycemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hypoglycaemia, hypoglycæmia, low blood glucose, low blood sugar |

| |

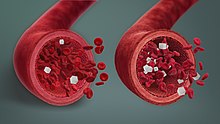

| Hypoglycemia (left) and normal blood sugar concentration (right) | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Headache, blurred vision, shakiness, dizziness, weakness, fatigue, sweating, clamminess, fast heart rate, anxiety, hunger, nausea, pins and needles sensation, difficulty talking, confusion, unusual behavior, lightheadedness, pale skin color, seizures[1][2][3][4][5] |

| Complications | Loss of consciousness, death |

| Usual onset | Rapid[1] |

| Causes | Medications (insulin, glinides and sulfonylureas), sepsis, kidney failure, certain tumors, liver disease[1][6] |

| Diagnostic method | Whipple's triad: Symptoms of hypoglycemia, serum blood glucose level <70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), and resolution of symptoms when blood glucose returns to normal[2] |

| Treatment | Eating foods high in simple sugars |

| Medication | Glucose, glucagon[1] |

| Frequency | In type 1 diabetics, mild hypoglycemia occurs twice per week on average, and severe hypoglycemia occurs once per year.[3] |

| Deaths | In type 1 diabetics, 6–10% will die of hypoglycemia.[3] |

The most common cause of hypoglycemia is medications used to treat diabetes such as insulin, sulfonylureas, and biguanides.[3][2][6] Risk is greater in diabetics who have eaten less than usual, recently exercised, or consumed alcohol.[1][3][2] Other causes of hypoglycemia include severe illness, sepsis, kidney failure, liver disease, hormone deficiency, tumors such as insulinomas or non-B cell tumors, inborn errors of metabolism, and several medications.[1][3][2] Low blood sugar may occur in otherwise healthy newborns who have not eaten for a few hours.[7]

Hypoglycemia is treated by eating a sugary food or drink, for example glucose tablets or gel, apple juice, soft drink, or lollies.[1][3][2] The person must be conscious and able to swallow.[1][3] The goal is to consume 10–20 grams of a carbohydrate to raise blood glucose levels to a minimum of 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).[3][2] If a person is not able to take food by mouth, glucagon by injection or insufflation may help.[1][3][8] The treatment of hypoglycemia unrelated to diabetes includes treating the underlying problem.[3][2]

Among people with diabetes, prevention starts with learning the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia.[3][2] Diabetes medications, like insulin, sulfonylureas, and biguanides can also be adjusted or stopped to prevent hypoglycemia.[3][2] Frequent and routine blood glucose testing is recommended.[1][3] Some may find continuous glucose monitors with insulin pumps to be helpful in the management of diabetes and prevention of hypoglycemia.[3]

Definition

editHypoglycemia, also called low blood sugar or low blood glucose, is a blood-sugar level below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).[3][5]

Blood-sugar levels naturally fluctuate throughout the day, the body normally maintaining levels between 70 and 110 mg/dL (3.9–6.1 mmol/L).[3][2] Although 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) is the lower limit of normal glucose, symptoms of hypoglycemia usually do not occur until blood sugar has fallen to 55 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L) or lower.[3][2] The blood-glucose level at which symptoms of hypoglycemia develop in someone with several prior episodes of hypoglycemia may be even lower.[2]

Whipple's triad

editThe symptoms of low blood sugar alone are not specific enough to characterize a hypoglycemic episode.[2] A single blood sugar reading below 70 mg/dL is also not specific enough to characterize a hypoglycemic episode.[2] Whipple's triad is a set of three conditions that need to be met to accurately characterize a hypoglycemic episode.[2]

The three conditions are the following:

- The signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia are present (see section below on Signs and Symptoms)[2][9]

- A low blood glucose measurement is present, typically less than 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L)[2]

- The signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia resolve after blood glucose levels have returned to normal[2]

Age

editThe biggest difference in blood glucose levels between the adult and pediatric population occurs in newborns during the first 48 hours of life.[7] After the first 48 hours of life, the Pediatric Endocrine Society cites that there is little difference in blood glucose level and the use of glucose between adults and children.[7] During the 48-hour neonatal period, the neonate adjusts glucagon and epinephrine levels following birth, which may cause temporary hypoglycemia.[7] As a result, there has been difficulty in developing guidelines on interpretation and treatment of low blood glucose in neonates aged less than 48 hours.[7] Following a data review, the Pediatric Endocrine Society concluded that neonates aged less than 48 hours begin to respond to hypoglycemia at serum glucose levels of 55–65 mg/dL (3.0–3.6 mmol/L).[7] This is contrasted by the value in adults, children, and older infants, which is approximately 80–85 mg/dL (4.4–4.7 mmol/L).[7]

In children who are aged greater than 48 hours, serum glucose on average ranges from 70 to 100 mg/dL (3.9–5.5 mmol/L), similar to adults.[7] Elderly patients and patients who take diabetes pills such as sulfonylureas are more likely to suffer from a severe hypoglycemic episode.[10][11] Whipple's triad is used to identify hypoglycemia in children who can communicate their symptoms.[7]

Differential diagnosis

editOther conditions that may present at the same time as hypoglycemia include the following:

- Alcohol or drug intoxication[2][12]

- Cardiac arrhythmia[2][12]

- Valvular heart disease[2][12]

- Postprandial syndrome[12]

- Hyperthyroidism[12]

- Pheochromocytoma[12]

- Post-gastric bypass hypoglycemia[2][12]

- Generalized anxiety disorder[12]

- Surreptitious insulin use[2][12]

- Lab or blood draw error (lack of antiglycolytic agent in collection tube or during processing)[13][12]

Signs and symptoms

editHypoglycemic symptoms are divided into two main categories.[3] The first category is symptoms caused by low glucose in the brain, called neuroglycopenic symptoms.[3] The second category of symptoms is caused by the body's reaction to low glucose in the brain, called adrenergic symptoms.[3]

| Neuroglycopenic symptoms | Adrenergic symptoms |

|---|---|

|

|

| References:[1][3][2][5][4][14][15] | |

Everyone experiences different symptoms of hypoglycemia, so someone with hypoglycemia may not have all of the symptoms listed above.[3][5][4] Symptoms also tend to have quick onset.[5] It is important to quickly obtain a blood glucose measurement in someone presenting with symptoms of hypoglycemia to properly identify the hypoglycemic episode.[5][2]

Pathophysiology

editGlucose is the main source of energy for the brain, and a number of mechanisms are in place to prevent hypoglycemia and protect energy supply to the brain.[3][16] The body can adjust insulin production and release, adjust glucose production by the liver, and adjust glucose use by the body.[3][16] The body naturally produces the hormone insulin, in an organ called the pancreas.[3] Insulin helps to regulate the amount of glucose in the body, especially after meals.[3] Glucagon is another hormone involved in regulating blood glucose levels, and can be thought of as the opposite of insulin.[3] Glucagon helps to increase blood glucose levels, especially in states of hunger.[3]

When blood sugar levels fall to the low-normal range, the first line of defense against hypoglycemia is decreasing insulin release by the pancreas.[3][16] This drop in insulin allows the liver to increase glycogenolysis.[3][16] Glycogenolysis is the process of glycogen breakdown that results in the production of glucose.[3][16] Glycogen can be thought of as the inactive, storage form of glucose.[3] Decreased insulin also allows for increased gluconeogenesis in the liver and kidneys.[3][16] Gluconeogenesis is the process of glucose production from non-carbohydrate sources, supplied from muscles and fat.[3][16]

Once blood glucose levels fall out of the normal range, additional protective mechanisms work to prevent hypoglycemia.[3][16] The pancreas is signaled to release glucagon, a hormone that increases glucose production by the liver and kidneys, and increases muscle and fat breakdown to supply gluconeogenesis.[3][17] If increased glucagon does not raise blood sugar levels to normal, the adrenal glands release epinephrine.[3][16] Epinephrine works to also increase gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, while also decreasing the use of glucose by organs, protecting the brain's glucose supply.[3][16]

After hypoglycemia has been prolonged, cortisol and growth hormone are released to continue gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, while also preventing the use of glucose by other organs.[3][16] The effects of cortisol and growth hormone are far less effective than epinephrine.[3][16] In a state of hypoglycemia, the brain also signals a sense of hunger and drives the person to eat, in an attempt to increase glucose.[3][16]

Causes

editHypoglycemia is most common in those with diabetes treated by insulin, glinides, and sulfonylureas.[3][2] Hypoglycemia is rare in those without diabetes, because there are many regulatory mechanisms in place to appropriately balance glucose, insulin, and glucagon.[3][2] Please refer to Pathophysiology section for more information on glucose, insulin, and glucagon.

Diabetics

editMedications

editThe most common cause of hypoglycemia in diabetics is medications used to treat diabetes such as insulin, sulfonylureas, and biguanides.[3][2][6] This is often due to excessive doses or poorly timed doses.[3] Sometimes diabetics may take insulin in anticipation of a meal or snack; then forgetting or missing eating that meal or snack can lead to hypoglycemia.[3] This is due to increased insulin without the presence of glucose from the planned meal.[3]

Hypoglycemic unawareness

editRecurrent episodes of hypoglycemia can lead to hypoglycemic unawareness, or the decreased ability to recognize hypoglycemia.[18][19][20] As diabetics experience more episodes of hypoglycemia, the blood glucose level which triggers symptoms of hypoglycemia decreases.[18][19][20] In other words, people without hypoglycemic unawareness experience symptoms of hypoglycemia at a blood glucose of about 55 mg/dL (3.0 mmol/L).[3][2] Those with hypoglycemic unawareness experience the symptoms of hypoglycemia at far lower levels of blood glucose.[18][19][20] This is dangerous for a number of reasons.[18][19][20] The hypoglycemic person not only gains awareness of hypoglycemia at very low blood glucose levels, but they also require high levels of carbohydrates or glucagon to recover their blood glucose to normal levels.[18][19][20] These individuals are also at far greater risk of severe hypoglycemia.[18][19][20]

While the exact cause of hypoglycemic unawareness is still under research, it is thought that these individuals progressively begin to develop fewer adrenergic-type symptoms, resulting in the loss of neuroglycopenic-type symptoms.[19][20] Neuroglycopenic symptoms are caused by low glucose in the brain, and can result in tiredness, confusion, difficulty with speech, seizures, and loss of consciousness.[3] Adrenergic symptoms are caused by the body's reaction to low glucose in the brain, and can result in fast heart rate, sweating, nervousness, and hunger.[3] See section above on Signs and Symptoms for further explanation of neuroglycopenic symptoms and adrenergic symptoms.

In terms of epidemiology, hypoglycemic unawareness occurs in 20–40% of type 1 diabetics.[18][20][21]

Other causes

editOther causes of hypoglycemia in diabetics include the following:

- Fasting, whether it be a planned fast or overnight fast, as there is a long period of time without glucose intake[1][3]

- Exercising more than usual as it leads to more use of glucose, especially by the muscles[1][3]

- Drinking alcohol, especially when combined with diabetic medications, as alcohol inhibits glucose production[1][3]

- Kidney disease, as insulin cannot be cleared out of circulation well[3]

Non-diabetics

editSerious illness

editSerious illness may result in low blood sugar.[1][3][2][16] Severe disease of many organ systems can cause hypoglycemia as a secondary problem.[3][2] Hypoglycemia is especially common in those in the intensive care unit or those in whom food and drink is withheld as a part of their treatment plan.[3][16]

Sepsis, a common cause of hypoglycemia in serious illness, can lead to hypoglycemia through many ways.[3][16] In a state of sepsis, the body uses large amounts of glucose for energy.[3][16] Glucose use is further increased by cytokine production.[3] Cytokines are a protein produced by the body in a state of stress, particularly when fighting an infection.[3] Cytokines may inhibit glucose production, further decreasing the body's energy stores.[3] Finally, the liver and kidneys are sites of glucose production, and in a state of sepsis those organs may not receive enough oxygen, leading to decreased glucose production due to organ damage.[3]

Other causes of serious illness that may cause hypoglycemia include liver failure and kidney failure.[3][16] The liver is the main site of glucose production in the body, and any liver failure or damage will lead to decreased glucose production.[3][16] While the kidneys are also sites of glucose production, their failure of glucose production is not significant enough to cause hypoglycemia.[3] Instead, the kidneys are responsible for removing insulin from the body, and when this function is impaired in kidney failure, the insulin stays in circulation longer, leading to hypoglycemia.[3]

Drugs

editA number of medications have been identified which may cause hypoglycemia, through a variety of ways.[3][2][22] Moderate quality evidence implicates the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin and the anti-malarial quinine.[3][2][22] Low quality evidence implicates lithium, used for bipolar disorder.[2][22] Finally, very low quality evidence implicates a number of hypertension medications including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (also called ACE-inhibitors), angiotensin receptor blockers (also called ARBs), and β-adrenergic blockers (also called beta blockers).[3][2][22] Other medications with very low quality evidence include the antibiotics levofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, progesterone blocker mifepristone, anti-arrhythmic disopyramide, anti-coagulant heparin, and chemotherapeutic mercaptopurine.[2][22]

If a person without diabetes accidentally takes medications that are traditionally used to treat diabetes, this may also cause hypoglycemia.[3][2] These medications include insulin, glinides, and sulfonylureas.[3][2] This may occur through medical errors in a healthcare setting or through pharmacy errors, also called iatrogenic hypoglycemia.[3]

Surreptitious insulin use

editWhen individuals take insulin without needing it, to purposefully induce hypoglycemia, this is referred to as surreptitious insulin use or factitious hypoglycemia.[3][2][23] Some people may use insulin to induce weight loss, whereas for others this may be due to malingering or factitious disorder, which is a psychiatric disorder.[23] Demographics affected by factitious hypoglycemia include women aged 30–40, particularly those with diabetes, relatives with diabetes, healthcare workers, or those with history of a psychiatric disorder.[3][23] The classic way to identify surreptitious insulin use is through blood work revealing high insulin levels with low C-peptide and proinsulin.[3][23]

Alcohol misuse

editThe production of glucose is blocked by alcohol.[3] In those who misuse alcohol, hypoglycemia may be brought on by a several-day alcohol binge associated with little to no food intake.[1][3] The cause of hypoglycemia is multifactorial, where glycogen becomes depleted in a state of starvation.[3] Glycogen stores are then unable to be repleted due to the lack of food intake, all compounded the inhibition of glucose production by alcohol.[3]

Hormone deficiency

editChildren with primary adrenal failure, also called Addison's disease, may experience hypoglycemia after long periods of fasting.[3] Addison's disease is associated with chronically low levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which leads to decreased glucose production.[3]

Hypopituitarism, leading to decreased growth hormone, is another cause of hypoglycemia in children, particularly with long periods of fasting or increased exercise.[3]

Inborn errors of metabolism

editBriefly, inborn errors of metabolism are a group of rare genetic disorders that are associated with the improper breakdown or storage of proteins, carbohydrates, or fatty acids.[24] Inborn errors of metabolism may cause infant hypoglycemia, and much less commonly adult hypoglycemia.[24]

Disorders that are related to the breakdown of glycogen, called glycogen storage diseases, may cause hypoglycemia.[3][24] Normally, breakdown of glycogen leads to increased glucose levels, particularly in a fasting state.[3] In glycogen storage diseases, however, glycogen cannot be properly broken down, leading to inappropriately decreased glucose levels in a fasting state, and thus hypoglycemia.[3] The glycogen storage diseases associated with hypoglycemia include type 0, type I, type III, and type IV, as well as Fanconi syndrome.[3]

Some organic and amino acid acidemias, especially those involving the oxidation of fatty acids, can lead to the symptom of intermittent hypoglycemia,[25][26] as for example in combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria (CMAMMA),[27][28][29] propionic acidemia[30][25] or isolated methylmalonic acidemia.[30][25]

Insulinomas

editA primary B-cell tumor, such as an insulinoma, is associated with hypoglycemia.[3] This is a tumor located in the pancreas.[3] An insulinoma produces insulin, which in turn decreases glucose levels, causing hypoglycemia.[3] Normal regulatory mechanisms are not in place, which prevent insulin levels from falling during states of low blood glucose.[3] During an episode of hypoglycemia, plasma insulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin will be inappropriately high.[3]

Non-B cell tumors

editHypoglycemia may occur in people with non-B cell tumors such as hepatomas, adrenocorticoid carcinomas,[31] and carcinoid tumors.[3] These tumors lead to a state of increased insulin, specifically increased insulin-like growth factor II, which decreases glucose levels.[3]

Post-gastric bypass postprandial hypoglycemia

editThe Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, is a weight-loss surgery performed on the stomach, and has been associated with hypoglycemia, called post-gastric bypass postprandial hypoglycemia.[3] Although the entire mechanism of hypoglycemia following this surgery is not fully understood, it is thought that meals cause very high levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 (also called GLP-1), a hormone that increases insulin, causing glucose levels to drop.[3]

Autoimmune hypoglycemia

editAntibodies can be formed against insulin, leading to autoimmune hypoglycemia.[3][32] Antibodies are immune cells produced by the body, that normally attack bacteria and viruses, but sometimes can attack normal human cells, leading to an autoimmune disorder.[33] In autoimmune hypoglycemia, there are two possible mechanisms.[3][32] In one instance, antibodies bind to insulin following its release associated with a meal, resulting in insulin being non-functional.[3][32] At a later time, the antibodies fall off insulin, causing insulin to be functional again leading late hypoglycemia after a meal, called late postprandial hypoglycemia.[3][32] Another mechanism causing hypoglycemia is due to antibodies formed against insulin receptors, called insulin receptor antibodies.[3][32] The antibodies attach to insulin receptors and prevent insulin breakdown, or degradation, leading to inappropriately high insulin levels and low glucose levels.[3][32]

Neonatal hypoglycemia

editLow blood sugar may occur in healthy neonates aged less than 48 hours who have not eaten for a few hours.[7] During the 48-hour neonatal period, the neonate adjusts glucagon and epinephrine levels following birth, which may trigger transient hypoglycemia.[7] In children who are aged greater than 48 hours, serum glucose on average ranges from 70 to 100 mg/dL (3.9–5.5 mmol/L), similar to adults, with hypoglycemia being far less common.[7]

Diagnostic approach

editThe most reliable method of identifying hypoglycemia is through identifying Whipple's triad.[3][2] The components of Whipple's triad are a blood sugar level below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), symptoms related to low blood sugar, and improvement of symptoms when blood sugar is restored to normal.[3][2] Identifying Whipple's triad in a patient helps to avoid unnecessary diagnostic testing and decreases healthcare costs.[2]

In those with a history of diabetes treated with insulin, glinides, or sulfonylurea, who demonstrate Whipple's triad, it is reasonable to assume the cause of hypoglycemia is due to insulin, glinides, or sulfonylurea use.[2] In those without a history of diabetes with hypoglycemia, further diagnostic testing is necessary to identify the cause.[2] Testing, during an episode of hypoglycemia, should include the following:

- Plasma glucose level, not point-of-care measurement[3][2]

- Insulin level[3][2]

- C-peptide level[3][2]

- Proinsulin level[3][2]

- Beta-hydroxybutyrate level[3][2]

- Oral hypoglycemic agent screen[2]

- Response of blood glucose level to glucagon[2]

- Insulin antibodies[2]

If necessary, a diagnostic hypoglycemic episode can be produced in an inpatient or outpatient setting.[3] This is called a diagnostic fast, in which a patient undergoes an observed fast to cause a hypoglycemic episode, allowing for appropriate blood work to be drawn.[3] In some, the hypoglycemic episode may be reproduced simply after a mixed meal, whereas in others a fast may last up to 72 hours.[3][2]

In those with a suspected insulinoma, imaging is the most reliable diagnostic technique, including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) imaging, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[3][2]

Treatment

editAfter hypoglycemia in a person is identified, rapid treatment is necessary and can be life-saving.[1] The main goal of treatment is to raise blood glucose back to normal levels, which is done through various ways of administering glucose, depending on the severity of the hypoglycemia, what is on-hand to treat, and who is administering the treatment.[1][3] A general rule used by the American Diabetes Association is the "15-15 Rule," which suggests consuming or administering 15 grams of a carbohydrate, followed by a 15-minute wait and re-measurement of blood glucose level to assess if blood glucose has returned to normal levels.[5]

Self-treatment

editIf an individual recognizes the symptoms of hypoglycemia coming on, blood sugar should promptly be measured, and a sugary food or drink should be consumed.[1] The person must be conscious and able to swallow.[1][3] The goal is to consume 10–20 grams of a carbohydrate to raise blood glucose levels to a minimum of 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).[3][2]

Examples of products to consume are:

- Glucose tabs or gel (refer to instructions on packet)[1][2]

- Juice containing sugar like apple, grape, or cranberry juice, 4 ounces or 1/2 cup[1][2]

- Soda or a soft-drink, 4 ounces or 1/2 cup (not diet soda)[2]

- Candy[2]

- Table sugar or honey, 1 tablespoon[1]

Improvement in blood sugar levels and symptoms are expected to occur in 15–20 minutes, at which point blood sugar should be measured again.[3][2] If the repeat blood sugar level is not above 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), consume another 10–20 grams of a carbohydrate and remeasure blood sugar levels after 15–20 minutes.[3][2] Repeat until blood glucose levels have returned to normal levels.[3][2] The greatest improvements in blood glucose will be seen if the carbohydrate is chewed or drunk, and then swallowed.[34] This results in the greatest bioavailability of glucose, meaning the greatest amount of glucose enters the body producing the best possible improvements in blood glucose levels.[34] A 2019 systematic review suggests, based on very limited evidence, that oral administration of glucose leads to a bigger improvement in blood glucose levels when compared to buccal administration.[35] This same review reported that, based on limited evidence, no difference was found in plasma glucose when administering combined oral and buccal glucose (via dextrose gel) compared to only oral administration.[35] The second best way to consume a carbohydrate it to allow it to dissolve under the tongue, also referred to as sublingual administration.[34] For example, a hard candy can be dissolved under the tongue, however the best improvements in blood glucose will occur if the hard candy is chewed and crushed, then swallowed.[34]

After correcting blood glucose levels, people may consume a full meal within one hour to replenish glycogen stores.[2]

Education

editFamily, friends, and co-workers of a person with diabetes may provide life-saving treatment in the case of a hypoglycemic episode[1] It is important for these people to receive training on how to recognize hypoglycemia, what foods to help the hypoglycemic eat, how to administer injectable or intra-nasal glucagon, and how to use a glucose meter.[1]

Treatment by family, friends, or co-workers

editFamily, friends, and co-workers of those with hypoglycemia are often first to identify hypoglycemic episodes, and may offer help.[3] Upon recognizing the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia in a diabetic, a blood sugar level should first be measured using a glucose meter.[1] If blood glucose is below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), treatment will depend on whether the person is conscious and can swallow safely.[3][2] If the person is conscious and able to swallow, the family, friend, or co-worker can help the hypoglycemic consume 10–20 grams of a carbohydrate to raise blood glucose levels to a minimum of 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).[2] Improvement in blood sugar level and symptoms is expected to occur in 15–20 minutes, at which point blood sugar is measured again.[3][2] If the repeat blood sugar level is not above 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), the hypoglycemic should consume another 10–20 grams of a carbohydrate and with remeasurement of blood sugar levels after 15–20 minutes.[3][2] Repeat until blood glucose levels have returned to normal levels, or call emergency services for further assistance.[2]

If the person is unconscious, a glucagon kit may be used to treat severe hypoglycemia, which delivers glucagon either by injection into a muscle or through nasal inhalation.[2][3][16] In the United States, glucacon kits are available by prescription for diabetic patients to carry in case of an episode of severe hypoglycemia.[36][37] Emergency services should be called for further assistance.[2]

Treatment by medical professionals

editIn a healthcare setting, treatment depends on the severity of symptoms and intravenous access.[38] If a patient is conscious and able to swallow safely, food or drink may be administered, as well as glucose tabs or gel.[38] In those with intravenous access, 25 grams of 50% dextrose is commonly administered.[38] When there is no intravenous access, intramuscular or intra-nasal glucagon may be administered.[38]

Other treatments

editWhile the treatment of hypoglycemia is typically managed with carbohydrate consumption, glucagon injection, or dextrose administration, there are some other treatments available.[3] Medications like diazoxide and octreotide decrease insulin levels, increasing blood glucose levels.[3] Dasiglucagon was approved for medical use in the United States in March 2021, to treat severe hypoglycemia.[39] Dasiglucagon (brand name Zegalogue) is unique because it is glucagon in a prefilled syringe or auto-injector pen, as opposed to traditional glucagon kits that require mixing powdered glucagon with a liquid.[39]

The soft drink Lucozade has been used for hypoglycemia in the United Kingdom, but it has recently replaced much of its glucose with artificial sweeteners, which do not treat hypoglycemia.[40]

Prevention

editDiabetics

editThe prevention of hypoglycemia depends on the cause.[1][3][2] In those with diabetes treated by insulin, glinides, or sulfonylurea, the prevention of hypoglycemia has a large focus on patient education and medication adjustments.[1][3][2] The foundation of diabetes education is learning how to recognize the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, as well as learning how to act quickly to prevent worsening of an episode.[2] Another cornerstone of prevention is strong self-monitoring of blood glucose, with consistent and frequent measurements.[2] Research has shown that patients with type 1 diabetes who use continuous glucose monitoring systems with insulin pumps significantly improve blood glucose control.[41][42][43] Insulin pumps help to prevent high glucose spikes, and help prevent inappropriate insulin dosing.[42][43][44] Continuous glucose monitors can sound alarms when blood glucose is too low or too high, especially helping those with nocturnal hypoglycemia or hypoglycemic unawareness.[42][43][44] In terms of medication adjustments, medication doses and timing can be adjusted to prevent hypoglycemia, or a medication can be stopped altogether.[3][2]

Non-diabetics

editIn those with hypoglycemia who do not have diabetes, there are a number of preventative measures dependent on the cause.[1][3][2] Hypoglycemia caused by hormonal dysfunction like lack of cortisol in Addison's disease or lack of growth hormone in hypopituitarism can be prevented with appropriate hormone replacement.[3][2] The hypoglycemic episodes associated with non-B cell tumors can be decreased following surgical removal of the tumor, as well as following radiotherapy or chemotherapy to reduce the size of the tumor.[3][2] In some cases, those with non-B cell tumors may have hormone therapy with growth hormone, glucocorticoid, or octreotide to also lessen hypoglycemic episodes.[3][2] Post-gastric bypass hypoglycemia can be prevented by eating smaller, more frequent meals, avoiding sugar-filled foods, as well as medical treatment with an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, diazoxide, or octreotide.[3][2]

Some causes of hypoglycemia require treatment of the underlying cause to best prevent hypoglycemia.[2] This is the case for insulinomas which often require surgical removal of the tumor for hypoglycemia to remit.[2] In patients who cannot undergo surgery for removal of the insulinoma, diazoxide or octreotide may be used.[2]

Epidemiology

editHypoglycemia is common in people with type 1 diabetes, and in people with type 2 diabetes taking insulin, glinides, or sulfonylurea.[1][3] It is estimated that type 1 diabetics experience two mild, symptomatic episodes of hypoglycemia per week.[3] Additionally, people with type 1 diabetes have at least one severe hypoglyemic episode per year, requiring treatment assistance.[3] In terms of mortality, hypoglycemia causes death in 6–10% of type 1 diabetics.[3][verification needed]

In those with type 2 diabetes, hypoglycemia is less common compared to type 1 diabetics, because medications that treat type 2 diabetes like metformin, glitazones, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, do not cause hypoglycemia.[1][3] Hypoglycemia is common in type 2 diabetics who take insulin, glinides, or sulfonylurea.[1][3] Insulin use remains a key risk factor in developing hypoglycemia, regardless of diabetes type.[1][3]

History

editHypoglycemia was first discovered by James Collip when he was working with Frederick Banting on purifying insulin in 1922.[45] Collip was asked to develop an assay to measure the activity of insulin.[45] He first injected insulin into a rabbit, and then measured the reduction in blood-glucose levels.[45] Measuring blood glucose was a time-consuming step.[45] Collip observed that if he injected rabbits with a too large a dose of insulin, the rabbits began convulsing, went into a coma, and then died.[45] This observation simplified his assay.[45] He defined one unit of insulin as the amount necessary to induce this convulsing hypoglycemic reaction in a rabbit.[45] Collip later found he could save money, and rabbits, by injecting them with glucose once they were convulsing.[45]

Etymology

editThe word hypoglycemia is also spelled hypoglycaemia or hypoglycæmia. The term means 'low blood sugar' from Greek ὑπογλυκαιμία, from ὑπο- hypo- 'under' + γλυκύς glykys 'sweet' + αἷμᾰ haima 'blood'.[46]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). "Low Blood Glucose (Hypoglycemia)". NIDDK.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, Heller SR, Montori VM, Seaquist ER, Service FJ (March 2009). "Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (3): 709–728. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1410. PMID 19088155.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz ea eb ec ed ee ef eg eh ei ej ek el em en Jameson JL, Kasper DL, Longo DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Loscalzo J (2018). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (20th ed.). New York. ISBN 978-1-259-64403-0. OCLC 1029074059. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Young VB (2016). Blueprints medicine. William A. Kormos, Davoren A. Chick (6th ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4698-6415-0. OCLC 909025539. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g American Diabetes Association (ADA). "Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Glucose)". www.diabetes.org. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Yanai H, Adachi H, Katsuyama H, Moriyama S, Hamasaki H, Sako A (February 2015). "Causative anti-diabetic drugs and the underlying clinical factors for hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes". World Journal of Diabetes. 6 (1): 30–36. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i1.30. PMC 4317315. PMID 25685276.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, Harris D, Haymond MW, Hussain K, et al. (August 2015). "Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for Evaluation and Management of Persistent Hypoglycemia in Neonates, Infants, and Children". The Journal of Pediatrics. 167 (2): 238–245. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.03.057. PMID 25957977. S2CID 10681217.

- ^ "FDA approves first treatment for severe hypoglycemia that can be administered without an injection". FDA. 11 September 2019. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ Mathew P, Thoppil D (2024), "Hypoglycemia", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30521262, retrieved 16 August 2024

- ^ "Low Blood Sugar (Hypoglycemia)". diabetesdaily.com. 8 August 2021.

- ^ Ling S, Zaccardi F, Lawson C, Seidu SI, Davies MJ, Khunti K (1 April 2021). "Glucose Control, Sulfonylureas, and Insulin Treatment in Elderly People With Type 2 Diabetes and Risk of Severe Hypoglycemia and Death: An Observational Study". Diabetes Care. 44 (4): 915–924. doi:10.2337/dc20-0876. ISSN 1935-5548. PMID 33541857.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Vella A. "Hypoglycemia in adults without diabetes mellitus: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and causes". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ "Low Blood Glucose (Hypoglycemia) - NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Hangry is officially a word in the Oxford English Dictionary". ABC News. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "If you've ever been hangry, this is what your body may be telling you". Washington Post. 9 July 2018. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Mathew P, Thoppil D (2022). "Hypoglycemia". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30521262. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Rix I, Nexøe-Larsen C, Bergmann NC, Lund A, Knop FK (2000). "Glucagon Physiology". In Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, et al. (eds.). Endotext. PMID 25905350. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Johnson-Rabbett B, Seaquist ER (September 2019). "Hypoglycemia in diabetes: The dark side of diabetes treatment. A patient-centered review". Journal of Diabetes. 11 (9): 711–718. doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12933. PMID 30983138. S2CID 115202581.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ibrahim M, Baker J, Cahn A, Eckel RH, El Sayed NA, Fischl AH, et al. (November 2020). "Hypoglycaemia and its management in primary care setting" (PDF). Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 36 (8): e3332. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3332. PMID 32343474. S2CID 216594548.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Martín-Timón I, Del Cañizo-Gómez FJ (July 2015). "Mechanisms of hypoglycemia unawareness and implications in diabetic patients". World Journal of Diabetes. 6 (7): 912–926. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i7.912. PMC 4499525. PMID 26185599.

- ^ Lucidi P, Porcellati F, Bolli GB, Fanelli CG (August 2018). "Prevention and Management of Severe Hypoglycemia and Hypoglycemia Unawareness: Incorporating Sensor Technology". Current Diabetes Reports. 18 (10): 83. doi:10.1007/s11892-018-1065-6. PMID 30121746. S2CID 52039366.

- ^ a b c d e Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Wang AT, Sheidaee N, Mullan RJ, Elamin MB, et al. (March 2009). "Clinical review: Drug-induced hypoglycemia: a systematic review". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (3): 741–745. doi:10.1210/jc.2008-1416. PMID 19088166.

- ^ a b c d Awad DH, Gokarakonda SB, Ilahi M (2022). "Factitious Hypoglycemia". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31194450. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Jeanmonod R, Asuka E, Jeanmonod D (2022). "Inborn Errors Of Metabolism". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29083820. Archived from the original on 13 October 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Ozand PT (2000). "Hypoglycemia in association with various organic and amino acid disorders". Seminars in Perinatology. 24 (2): 172–193. doi:10.1053/sp.2000.6367. PMID 10805172.

- ^ Baker JJ, Burton BK (November 2021). "Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Long-chain Fatty-acid Oxidation Disorders: A Review". TouchREVIEWS in Endocrinology. 17 (2): 108–111. doi:10.17925/EE.2021.17.2.108. ISSN 2752-5457. PMC 8676101. PMID 35118456.

- ^ NIH Intramural Sequencing Center Group, Sloan JL, Johnston JJ, Manoli I, Chandler RJ, Krause C, Carrillo-Carrasco N, Chandrasekaran SD, Sysol JR, O'Brien K, Hauser NS, Sapp JC, Dorward HM, Huizing M, Barshop BA (2011). "Exome sequencing identifies ACSF3 as a cause of combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria". Nature Genetics. 43 (9): 883–886. doi:10.1038/ng.908. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 3163731. PMID 21841779.

- ^ Wehbe Z, Behringer S, Alatibi K, Watkins D, Rosenblatt D, Spiekerkoetter U, Tucci S (2019). "The emerging role of the mitochondrial fatty-acid synthase (mtFASII) in the regulation of energy metabolism". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1864 (11): 1629–1643. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.07.012. PMID 31376476. S2CID 199404906.

- ^ Levtova A, Waters PJ, Buhas D, Lévesque S, Auray-Blais C, Clarke JT, Laframboise R, Maranda B, Mitchell GA, Brunel-Guitton C, Braverman NE (2019). "Combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria due to ACSF3 mutations: Benign clinical course in an unselected cohort". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 42 (1): 107–116. doi:10.1002/jimd.12032. ISSN 0141-8955. PMID 30740739. S2CID 73436689.

- ^ a b Ozand PT, Al-Essa M (2012), Elzouki AY, Harfi HA, Nazer HM, Stapleton FB (eds.), "Disorders of Organic Acid and Amino Acid Metabolism", Textbook of Clinical Pediatrics, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 451–514, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02202-9_38, ISBN 978-3-642-02201-2

- ^ "Adrenocortical Carcinoma Treatment - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 6 July 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Lupsa BC, Chong AY, Cochran EK, Soos MA, Semple RK, Gorden P (May 2009). "Autoimmune forms of hypoglycemia". Medicine. 88 (3): 141–153. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181a5b42e. PMID 19440117. S2CID 34429211.

- ^ "Antibody". Genome.gov. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d De Buck E, Borra V, Carlson JN, Zideman DA, Singletary EM, Djärv T (April 2019). "First aid glucose administration routes for symptomatic hypoglycaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD013283. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd013283.pub2. PMC 6459163. PMID 30973639.

- ^ a b De Buck E, Borra V, Carlson JN, Zideman DA, Singletary EM, Djärv T, et al. (Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group) (April 2019). "First aid glucose administration routes for symptomatic hypoglycaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (4): CD013283. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013283.pub2. PMC 6459163. PMID 30973639.

- ^ "Severe Low Blood Sugar (Hypoglycemia) Treatment | Lilly GLUCAGON". www.lillyglucagon.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Glucacon Emergency Kit". Glucagon Emergency Kit. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d Pasala S, Dendy JA, Chockalingam V, Meadows RY (2013). "An inpatient hypoglycemia committee: development, successful implementation, and impact on patient safety". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (3): 407–412. PMC 3776519. PMID 24052773.

- ^ a b "HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. These highlights do not include all the information needed to use ZEGALOGUE® safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for ZEGALOGUE. ZEGALOGUE (dasiglucagon) injection, for subcutaneous use" (PDF). Accessdate.fsa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Harrold A. "Diabetic patients should be warned about changes to Lucozade glucose content". Nursing in Practice. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Langendam M, Luijf YM, Hooft L, Devries JH, Mudde AH, Scholten RJ (January 2012). "Continuous glucose monitoring systems for type 1 diabetes mellitus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD008101. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008101.pub2. PMC 6486112. PMID 22258980.

- ^ a b c Azhar A, Gillani SW, Mohiuddin G, Majeed RA (2020). "A systematic review on clinical implication of continuous glucose monitoring in diabetes management". Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences. 12 (2): 102–111. doi:10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_7_20. PMC 7373113. PMID 32742108.

- ^ a b c Mian Z, Hermayer KL, Jenkins A (November 2019). "Continuous Glucose Monitoring: Review of an Innovation in Diabetes Management". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 358 (5): 332–339. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2019.07.003. PMID 31402042. S2CID 199047204.

- ^ a b "Continuous Glucose Monitoring | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Collip discovers hypoglycemia". Treating Diabetes. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Non-Diabetic Hypoglycemia | Causes, Symptoms & Treatment". study.com. 21 November 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

External links

edit- Hypoglycemia at the Mayo Clinic

- American Diabetes Association

- "Hypoglycemia". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.