Guayama (Spanish: [ɡwaˈʝama], locally [waˈʝama]), officially the Autonomous Municipality of Guayama (Spanish: Municipio Autónomo de Guayama), is a city and municipality on the Caribbean coast of Puerto Rico. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the city had a population of 36,614. It is the center of the Guayama metropolitan area with a population of 68,442 in 2020.

Guayama, Puerto Rico

Municipio Autónomo de Guayama | |

|---|---|

| Autonomous Municipality of Guayama | |

From top, left to right: Iglesia de San Antonio de Padua; Casa Cautiño; Colón Town Square; PR-54; Teatro Guayama; Hacienda Vives | |

| Nicknames: "La ciudad del Guamaní" Spanish for "The City of the Guamaní" "El pueblo de los brujos" Spanish for "The Witch City" | |

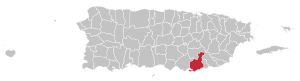

Map of Puerto Rico highlighting Guayama Municipality | |

| Coordinates: 17°58′27″N 66°06′36″W / 17.97417°N 66.11000°W[1] | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Commonwealth | |

| Founded | January 29, 1736 |

| Founded by | Matías de Abadía |

| Barrios | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor 2022 | O'Brian Vázquez Molina |

| Area | |

| 106.8 sq mi (277 km2) | |

| • Land | 65.0 sq mi (168 km2) |

| • Water | 41.8 sq mi (108 km2) |

| Elevation | 239 ft (73 m) |

| Population | |

| 36,614 | |

| • Rank | 30th in Puerto Rico |

| • Density | 340/sq mi (130/km2) |

| • Metro | 68,442 (MSA) |

| Demonym | Guayameses[4] |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (Atlantic (AST)) |

| ZIP Codes | 00784, 00785 |

| Area code | 787/939 |

| Major routes | |

| GNIS feature ID | 1610860[2] |

| Website | www |

Etymology and nicknames

editThe original name of the city is San Antonio de Padua de Guayama, named after the saint Anthony of Padua; as with other settlement names in Puerto Rico, the name was eventually shortened to Guayama. Guayama comes from the name of a Taíno cacique (chief), who was leader of the tribes in the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico. The Taíno word Guayama (wayama) is said to mean "great place" or "big open space".[6] Another legend tells that the name of the town comes from the name of a woman called Juana Guayama who is said to have been an early owner of the land around Guayama and granter of the land in modern-day Machete where the town was later founded.[7]

The first nickname of the city was Ciudad del Guamaní ("city of the Guamaní [River]") after the river that crosses the municipality. The name of this river might be related to the name Guayama, and it has been important to the city since its early founding.[8] A more modern and more popular nickname for the city is Pueblo de los brujos ("town of witches" or "town of warlocks") or Pueblo brujo ("witch town"). This nickname traces its origins to a popular story that tells that residents of the city would bring a kind of leaf called hoja bruja ("witch leaf") to baseball games to "scare" the opposing team by pretending to cast spells on them. The town's baseball team then adopted the hoja bruja as their symbol.[7] Another story tells that the nickname comes from a legendary baseball player from the city's local team, Moncho El Brujo, who according to legend owed his success as a pitcher to witchcraft.[9] Regardless of the origin of the nickname, residents of Guayama are often called brujos and their basketball team now carries the name Brujos de Guayama ("Guayama Warlocks").[10]

History

editDuring the early years of the Spanish colonization, the region known today as Guayama was inhabited by Taíno native people. The indigenous population in this area decreased due to slavery and migration to the Lesser Antilles. The following centuries, the region was under attack from the Taíno rebellion, Caribs and pirates. The town was founded on January 29, 1736, as San Antonio de Padua de Guayama by then Spanish Governor Matías de Abadía, although there is knowledge of it being populated by native people as early as 1567. It was Governor Don Tomás de Abadía who officially declared Guayama a "pueblo" (town) with the name of San Antonio de Padua de Guayama. That same year the Catholic church in town, San Antonio de Padua, was declared a Parish. In 1776, Guayama had 200 houses, the church and a central plaza and the total population was approximately 5,000 villagers. Construction on Guayama's Parroquial church of San Antonio de Padua began in 1827 and was completed 40 years later. In 1828 the construction of the King's House (Casa del Rey) was completed and the church was rebuilt as well. Earlier that year, Guayama was hit by a terrible fire that destroyed 57 houses and 9 huts. Guayama territorial order was altered at different times through the years. Some of the most populated neighborhoods were segregated to form new towns. Patillas was established in 1811 as an independent municipality. In 1831, the territory comprised the neighborhoods: Algarrobos, Ancones, Arroyo, Carreras, Guayama Pueblo, Guamaní, Jobos, Machete, and Yaurel. Later, Arroyo was divided into Arroyo Este and Arroyo Oeste and neighborhoods emerged: Pozo Hondo, Palmas de Aguamanil, Caimital, Pitajayas, Cuatro Calles, Sabana Eneas, Palmas, and Salinas. The latter had been segregated from Coamo.

In 1855, Arroyo was separated to become an independent municipality, taking the neighborhoods: Ancones, Arroyo, Yaurel, Pitajaya, and Cuatro Calles. By 1878, Guayama was a department head including: Comerío (then Sabana del Palmar), Cidra, Cayey, Salinas, Arroyo, San Lorenzo (then called Hato Grande), Aguas Buenas, Caguas, Gurabo, and Juncos. The development continued with the construction of the town cemetery in 1844, the slaughterhouse and meat market in 1851, and a wooden theater of two levels in 1878. By then Guayama had fourteen sugar plantations operating with steam engines and three with ox mills. Also practiced in this municipality was the exploitation of lead mines by the company "La Estrella", owned by Miguel Planellas, as well as the mineral galena, by the company "La Rosita", owned by Antonio Aponte. In 1881, Guayama is declared a Villa (First Order Municipality).

During the Spanish–American War, American forces under General Nelson A. Miles landed at Guánica near Ponce on July 25, 1898. The landing surprised the United States War Department no less than the Spanish, as Miles had been instructed to land near San Juan (the War Department learned of the landing through an Associated Press release.) However, en route to Puerto Rico Miles concluded that a San Juan landing was vulnerable to attack by small boats, and so changed plans. Ponce, said at the time to be the largest city in Puerto Rico, was connected with San Juan by a 110-kilometre (70 mi) military road, well defended by the Spanish at Coamo and Aibonito. In order to flank this position, American Major General John R. Brooke landed at Arroyo, just east of Guayama, intending to move on Cayey, which is northwest of Guayama, along the road from Ponce to San Juan. General Brooke occupied Guayama August 5, 1898, after slight opposition, in the Battle of Guayama. On August 9, the Battle of Guamaní took place north of Guayama. A more significant battle, the Battle of Aibonito Pass, was halted on the morning of August 13 upon notification of the armistice between the United States and Spain.

Puerto Rico was ceded by Spain in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War under the terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and became a territory of the United States. In 1899, the United States Department of War conducted a census of Puerto Rico finding that the population of Guayama was 12,749.[11]

After the Spanish–American War, Guayama continued to develop. The Bernardini Theater built by engineer Manuel Texidor y Alcalá del Olmo opened in 1913. The venue, property of attorney Thomas Bernardini, was the scene for artists of international fame. By that time, Guayama was considered one of the most important cities on the island's social scene.

In the early twentieth century, there were selected societies such as the 'Coliseo Derkes' and 'Grupo Primavera', which endowed performing arts as well as scientific events. By the mid-twentieth century, Guayama achieved great industrial development, especially with the establishment of Univis Optical Corp., Angela Manufacturing Company and a petrochemical complex of the Phillips Petroleum Company. In 1968, the company started production of paraffin, benzene, synthetic fibers, nylon, plastic anhydrous, a 3,800,000 litres (830,000 imp gal; 1,000,000 US gal) of gasoline a day, and many other products. During that same decade agriculture began to decline as a result of land loss, industrialization and the construction of multiple housing developments. The urban growth affected the sugar cane industry. However, in 1974, 155,595 tons of sugar cane was harvested in the Municipality producing 12,655 tons of refined sugar.[12]

In November 2002, AES Puerto Rico opened its coal power plant in Guayama. The company transmits and distributes electricity through a 25-year contract with the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority. The 2012 National Puerto Rican Day Parade was dedicated to the Municipality of Guayama and its people.

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico. In Guayama, the hurricane triggered numerous landslides and caused major destruction with an estimated 2000 homes losing their roof. The river caused major flooding and people were left with no power.[13][14][15] After Hurricane Maria, the people of Guayama resorted to collecting spring water for their drinking water.[16]

Geography

editGuayama is located at 17°58′27″N 66°06′36″W / 17.974241°N 66.110034°W.[1][17]

The Municipality of Guayama is located on the Southern Coastal Valley region, bordering the Caribbean Sea, south of Cayey; east of Salinas; and west of Patillas and Arroyo. Guayama's municipal territory reaches the central mountain range to the north and the Caribbean Sea to the south. The mountain systems Sierra de Jájome (2,395 feet or 730 meters) and Sierra de Cayey cover some of the municipality area. The highest points are the Cerro de la Tabla (2,834 feet or 863 meters) and Cerro Tumbado (2,450 feet or 746 meters), which are part of the Sierra de Cayey mountain system. Other elevations are the mountains Garau, Charcas and Peña Hendida. Parts of the Guavate-Carite Forest and the Aguirre State Forest are in Guayama. The Guavate-Carite Forest, a 2,400-hectare (6,000-acre) nature reserve is inhabited by 50 species of birds, making this spot a recognized area for birding and has a reserve with a dwarf forest that was produced by the region's high humidity and moist soil. The Aguirre Forest includes: mangroves, tidal flats, bird rookeries, research lakes & large manatee population. The Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve was established in 1987. The reserve is located between the coasts of Salinas and Guayama, approximately 1,167 hectares (2,883 acres) of mangrove forest and freshwater wetlands. The two main components: Mar Negro mangrove forest, which consists of a mangrove forest and a complex system of lagoons and channels interspersed with salt and mud flats; and Cayos Caribe Islets, which are surrounded by coral reefs and seagrass beds, with small beach deposits and upland areas.

Features

edit- Islands include Cayo Caribes, Isla Morrillito and Mata Redonda.

- Carite Dam

- Gorges; Barros, Branderí, Cimarrona, Corazón, Culebra, Palmas Bajas, and Salada.

- Lakes: Melania Lake, Carite Lake

- Las Mareas Lagoon

- Rivers: Río Chiquito, Río Guamaní, Río de la Plata and Río Seco.

Climate

editThe annual precipitation is approximately 1,300 millimetres (52 in) and the average temperature is 27 °C (81 °F).

| Climate data for Guayama, Puerto Rico (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1914–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 94 (34) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

98 (37) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 85.4 (29.7) |

85.5 (29.7) |

85.9 (29.9) |

86.9 (30.5) |

87.9 (31.1) |

88.8 (31.6) |

89.7 (32.1) |

90.0 (32.2) |

90.0 (32.2) |

89.3 (31.8) |

88.1 (31.2) |

86.5 (30.3) |

87.8 (31.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 78.7 (25.9) |

78.6 (25.9) |

78.9 (26.1) |

80.3 (26.8) |

81.8 (27.7) |

83.0 (28.3) |

83.6 (28.7) |

83.7 (28.7) |

83.4 (28.6) |

82.6 (28.1) |

81.3 (27.4) |

79.8 (26.6) |

81.3 (27.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 71.9 (22.2) |

71.7 (22.1) |

71.9 (22.2) |

73.7 (23.2) |

75.7 (24.3) |

77.2 (25.1) |

77.5 (25.3) |

77.4 (25.2) |

76.8 (24.9) |

76.0 (24.4) |

74.6 (23.7) |

73.0 (22.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

60 (16) |

61 (16) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

67 (19) |

65 (18) |

63 (17) |

62 (17) |

62 (17) |

60 (16) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.42 (61) |

1.70 (43) |

1.90 (48) |

2.84 (72) |

5.26 (134) |

4.58 (116) |

5.46 (139) |

7.08 (180) |

7.30 (185) |

7.22 (183) |

5.85 (149) |

2.79 (71) |

54.40 (1,382) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 14.5 | 13.1 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 15.9 | 16.6 | 17.2 | 18.5 | 16.0 | 17.5 | 16.2 | 15.1 | 185.1 |

| Source: NOAA[18][19] | |||||||||||||

Barrios

editLike all municipalities of Puerto Rico, Guayama is subdivided into barrios. The municipal buildings, central square and large Catholic church are located in a barrio referred to as "el pueblo".[20][21][22][23]

Population, per 2010 census: Algarrobo 6,959; Caimital 4,124; Carite 1,210; Carmen 619; Guamaní 1,455 ; Guayama Pueblo 16,891; Jobos 8,286; Machete 3,846; Palmas 709; Pozo Hondo 1,263; Total 45,362.[5]

Sectors

editBarrios (which are like minor civil divisions)[25] and subbarrios,[26] are further subdivided into smaller areas called sectores (sectors in English). The types of sectores may vary, from normally sector to urbanización to reparto to barriada to residencial, among others.[27][28][29]

Special Communities

editComunidades Especiales de Puerto Rico (Special Communities of Puerto Rico) are marginalized communities whose citizens are experiencing a certain amount of social exclusion. A map shows these communities occur in nearly every municipality of the Commonwealth. Of the 742 places that were on the list in 2014, the following barrios, communities, sectors, or neighborhoods were in Guayama: Borinquén, Comunidad Mosquito, Comunidad Puerto de Jobos, Loma del Viento, and Pueblito Del Carmen.[30]

Tourism

editTo stimulate local tourism, the Puerto Rico Tourism Company launched the Voy Turistiendo ("I'm Touring") campaign, with a passport book and website. The Guayama page lists Plaza de Recreo Cristobal Colón, Museo Casa Cuatiño, and Molino de Vives, as places of interest.[31]

Landmarks and places of interest

editIn 2015, Guayama launched its "grastromic route", with certified restaurants to meet the needs of tourists and locals alike.[32]

According to a news article by Primera Hora, Guayama has 19 beaches including Playa el Bohío.[33]

Other places of interest in Guayama include:

- San Antonio de Padua Church

- Guayama Town Plaza (Plaza pública Cristóbal Colón)

- Molino y Hacienda Azucarera Vives

- Casa Cautiño Museum

- Centro de Bellas Artes

- Teatro Calimano

- First Methodist Church (Built in 1902)

- Guayama Convention Center

- Céntrico Mall [34]

- El Legado Golf Resort

- Mariposario Las Limas Natural Reserve

- Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve

- Guavate-Carite Forest

- Aguirre State Forest

- Carite Lake

- Pozuelo Beach

- Rodeo Beach

- Fishing Club Guayama

Economy

editIndustry

editGuayama is home to various pharmaceutical and manufacturing companies, such as Pfizer, Baxter, Eli Lilly, and Tapi. A coal power plant operated by AES.

Health facilities

editThe San Lucas Episcopal Hospital, located on Pedro Albizu Campos Avenue and operated by the Episcopal Diocese of Puerto Rico and the Santa Rosa Hospital are the main medical facilities in Guayama. The Veterans Health Administration operates a Community-Based Outpatient Clinic (COBC) in the Municipality.

Culture

editGuayama is the birthplace of numerous artists and musicians who have significantly influenced Puerto Rican culture. During the 20th century, the literary culture of the city was influenced by performers including Afro-Antillano genre poet Luis Palés Matos and his father Vicente Palés Anés. Music composer Catalino "Tite" Curet Alonso who became a composer of over 2,000 salsa songs is also from Guayama, even though he was raised in the Santurce section of San Juan. Other performers born in Guayama include actresses Gilda Galán and Karla Monroig. The Casa Cautiño Museum is administered by the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture and include works of art, wood carvings, sculptures and furniture built by Puerto Rican cabinetmakers for the Cautiño family. The museum is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Festivals and events

editGuayama celebrates its patron saint festival in June. The Fiestas Patronales de San Antonio de Padua is a religious and cultural celebration that generally features parades, games, artisans, amusement rides, regional food, and live entertainment.[17][35]

Feria Dulce Sueño named after a famous Puerto Rican horse is held each March in Guayama. Dulce Sueño, the most influential sire in the modern Puerto Rican Paso Fino breed, was born in Guayama.[36][37]

Other festivals and events celebrated in Guayama include:

- Witches Carnival – March

- Guayama Carnival – April

- Sweet Dreams Fair – March

- Jíbaro Festival – October

- Puerto Rican Week – December

Sports

editGuayama had one of the Professional Baseball League founding teams, which won the Championship the first years of the league, 1938–39 and 1939–40. Guayama has a baseball team (Brujos de Guayama) in the Federación de Béisbol Aficionado de Puerto Rico that won the national championship in 1987. Guayama also used to have a basketball team in the Puerto Rico's BSN (Brujos de Guayama) that went to the League finals twice back in 1991 and 1994 but lost both times to eventual champions Atleticos de San German, it was announced that the team will return for the league's 2012 season.[38] The Guayama Convention Center hosted some of the roller skating events for the 2010 Central American and Caribbean Games that took place in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico from July 18, 2010, to August 1, 2010. El Legado Golf Resort, a 285 acres, 18 hole golf course founded in 2002 by Puerto Rican golf player Juan "Chi-Chi" Rodriguez. The Guayama Football Club, founded in 1949, plays in the Liga Puerto Rico.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 12,749 | — | |

| 1910 | 17,379 | 36.3% | |

| 1920 | 19,192 | 10.4% | |

| 1930 | 23,624 | 23.1% | |

| 1940 | 30,511 | 29.2% | |

| 1950 | 32,807 | 7.5% | |

| 1960 | 33,678 | 2.7% | |

| 1970 | 36,249 | 7.6% | |

| 1980 | 40,183 | 10.9% | |

| 1990 | 41,588 | 3.5% | |

| 2000 | 44,301 | 6.5% | |

| 2010 | 45,362 | 2.4% | |

| 2020 | 36,614 | −19.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39] 1899 (shown as 1900)[40] 1910-1930[41] 1930-1950[42] 1960–2000[43] 2010[22] 2020[44] | |||

As of the 2020 U.S. Census, the city had a population of 36,614. It is the center of the Guayama metropolitan area, which was home to 68,442 in 2020.

In terms of race and ethnicity, the 2010 U.S. Census stated the following concerning Guayameses:

- White: 72.8% (33,025)

- Black: 22.9% (10,367)

- American Indian/Indigenous: 1.7% (769)

- Asian: 0.2% (108)

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 0.1% (51)

- Some Other Race: 8.3.% (3,746)

Government

editThe mayor of Guayama as of May, 2022 is O'Brian Vázquez Molina.[46]

The city belongs to the Puerto Rico Senatorial district VI, which is represented by two senators. In 2012, Miguel Pereira Castillo and Angel M. Rodríguez were elected as district senators.[47]

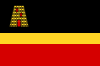

Symbols

editThe municipio has an official flag and coat of arms.[48]

Flag

editThe flag of Guayama is made up of three stripes of different colors: black, yellow, and red from top to bottom. The black stands for the enslaved Africans brought to Puerto Rico, many to Guayama. The yellow represents sugar cane industry in Puerto Rico and the significance of Guayama's sugar plantations. The red symbolizes the blood shed by Taíno Indians in their fight against the Spanish/European colonizers. To the left of the top stripe we can see the Old Mill, which today is known as the Molino de Vives.[49]

Coat of arms

editThe shield is divided in four parts and in two of them part of a chessboard appears. The chessboard pattern represents the center of the city, which resembles a chessboard. It has two old mill towers. The laurel trees constitute a representation of the beautiful Recreation Plaza very well known for its trimmed trees. The three silver flowers symbolize San Antonio de Padua, patron of Guayama. The crown represents Cacique Guayama, name of the town. The big crown has four towers.[49]

Education

editThe education system in Guayama has three public high schools, which are Francisco Garcia Boyrie, Adela Brenes Texidor and Dr. Rafael Lopez Landrón, and one vocational high school, Dra. Maria Socorro Lacot. Guayama also has a campus of the Puerto Rico Institute of Technology and the Inter American University of Puerto Rico, Guayama campus (Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Guayama in Spanish) Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico – Recinto de Guayama . It also has several private schools such as Academia San Antonio, Guamaní Private School, Saint Patrick's Bilingual School, Colegio Catòlico San Antonio, Fountain Christian Bilingual School, Escuela Superior and Academia Adventista Tres Angeles and more than 12 other public schools in the elementary and intermediate education levels.[50][51][52]

Transportation

editGuayama is served by multiple state highways, principally Puerto Rico Highway 54, Puerto Rico Highway 53, PR-3, PR-15, PR-179, PR-744, PR-748, and PR-7710. PR-54 serves as a by-pass route to PR-3 which crosses the pueblo. PR-54 also serves as the main route towards PR-53, connecting Guayama to the neighboring town of Salinas and PR-52, providing expressway access towards Ponce, San Juan, and Caguas. Just north of the Guayama barrio-pueblo is PR-748, which, along with the Conector Dulce Sueño forms a ring around Guayama’s urban area. PR-748 intercepts Olimpo and Caimital, eventually intersecting with the rural PR-15, connecting Guayama with Cayey. PR-179 is born out of PR-15, serving as the main route through barrios Guamaní and Carite until its intersection with PR-184 in Cayey. Just south of Guayama’s main urban area, PR-3 continues on its way to Salinas. It crosses through Jobos, right in front of its parish and continues to Salinas. PR-7710 serves as the only route to the coastal sector of Pozuelo, offering some of the best beaches Guayama has to offer. The Municipality is only 38 mi (61 km) away from Ponce and 58 mi (93 km) from San Juan via expressways PR-53 and PR-52. The nearest international airport is the Mercedita Airport in Ponce.

At one time during 1937, Guayama received domestic, commercial airline flights from San Juan on Puerto Rico's national airline, Puertorriqueña de Aviación.[53]

There are 28 bridges in Guayama.[54]

Notable Guayameses

edit- Jose C. Aponte Garcia - Puerto Rico Prosecuting Attorney during the Administrations of Luis Munoz Marin, Roberto Sanchez Vilella; Secretary of Justice during Roberto Sanchez Vilella's Administration

- Modesto Cartagena - Purple Heart recipient

- Catalino (Tite) Curet Alonso - composer of over 2,000 salsa songs.

- Diosa Costello - actress, AKA: The Original Latin Bombshell. True Name: Juana de Dios Castrello

- Luis Palés Matos - Puerto Rican poet who is credited with creating the poetry genre known as Afro-Antillano.

- Gilda Galán - Puerto Rican actress, dramaticist, comedian, writer, composer, scriptwriter and poet.[55]

- Rafael Pérez Perry - Businessman and a pioneer in Puerto Rico's radio and television broadcasting industry. In 1954 founded Puerto Rico's television Channel 11 (nowadays Univision Puerto Rico).

- Miguel Poventud - Puerto Rican musician, singer, actor and composer of Boleros.

- Pedro Garcia - Major League Baseball player for the Milwaukee Brewers, Detroit Tigers, and the Toronto Blue Jays

- Karla Monroig - Telenovela actress, model and television host.

- Roger Moret- Former Major League Baseball pitcher

- Juan Laporte -Former WBC featherweight boxing champion (1982–1984)

- Jaime Fuster Berlingeri- Associate Justice to the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico and former Resident Commissioner to the U.S. Congress.

- Marcos Crespo - Democratic member of the New York State Assembly representing the 85th Assembly District.

- Carmelo Delgado Delgado - Leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. Is thought to be the first U.S. citizen to die in Spain's civil war.

- Dr.Victor Manuel Blanco PhD - Scientist and astronomer who in 1959 discovered "Blanco 1," a galactic cluster.

- Eddie Rosario - Major League Baseball player for the Atlanta Braves and was the 2021 NLCS MVP.

- Leopoldo Santiago Lavandero (1912-2003) - playwright, theater producer and teacher.

- Plan B - reggaetón duo with multiple songs on the Billboard Hot Latin Songs charts.

- Ricky Sánchez - Former basketball player, drafted by the Portland Trail Blazers in 2005.

Gallery

edit-

The Guayama Convention Center

-

Plaza Guayama Mall

-

The central plaza and church of San Antonio de Padua in Guayama

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ a b "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Nicknames and Demonyms of the Towns of Puerto Rico" Archived 2012-01-05 at the Wayback Machine. (In Spanish). Center of Information Access. Interamerican University of Puerto Rico, Ponce. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Guayama". www.salonhogar.com. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Historia de Guayama | Brujos de Guayama | Guayama Puerto Rico". www.guayamapr.com. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Guayama" (in Spanish). Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ "Guayama Puerto Rico - Ciudad de los Brujos y del Guamaní". www.nuevaisla.com. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Eurobasket. "Brujos de Guayama basketball, News, Roster, Rumors, Stats, Awards, Transactions, Details-latinbasket". Eurobasket LLC. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Joseph Prentiss Sanger; Henry Gannett; Walter Francis Willcox (1900). Informe sobre el censo de Puerto Rico, 1899, United States. War Dept. Porto Rico Census Office. Washington: Govt. print. off. p. 160.

- ^ Medina-Carrillo, Norma. "Hacienda Esperanza, Molino Vives, Guayama Puerto Rico" (PDF). aperpuertorico.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "María, un nombre que no vamos a olvidar. El huracán María molió la costa y el campo de Guayama" [Maria, a name we will never forget. Hurricane Maria mowed down the coast and the Guayama countryside]. El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). June 13, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico". USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. October 27, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Preliminary Locations of Landslide Impacts from Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico" (PDF). USGS Landslide Hazards Program. USGS. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ^ Baez, Alvin (October 18, 2017). "The search for water in Puerto Rico". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 15, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ a b "Guayama Municipality". Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico. Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades (FPH). Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Guayama 2E, PR PQ". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Picó, Rafael; Buitrago de Santiago, Zayda; Berrios, Hector H. Nueva geografía de Puerto Rico: física, económica, y social, por Rafael Picó. Con la colaboración de Zayda Buitrago de Santiago y Héctor H. Berrios. San Juan Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Puerto Rico,1969. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Gwillim Law (May 20, 2015). Administrative Subdivisions of Countries: A Comprehensive World Reference, 1900 through 1998. McFarland. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4766-0447-3. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Puerto Rico:2010:population and housing unit counts.pdf (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ "Map of Guayama" (PDF). Welcome to Puerto Rico. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". Fact Finder on US Census. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ "US Census Barrio-Pueblo definition". factfinder.com. US Census. Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ "P.L. 94-171 VTD/SLD Reference Map (2010 Census): Guayama Municipio, PR" (PDF). www2.census.gov. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Economics and Statistics Administration U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ "Agencia: Oficina del Coordinador General para el Financiamiento Socioeconómico y la Autogestión (Proposed 2016 Budget)". Puerto Rico Budgets (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014), El vuelo de la esperanza: Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 (first ed.), San Juan, Puerto Rico Fundación Sila M. Calderón, ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0

- ^ "Leyes del 2001". Lex Juris Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Rivera Quintero, Marcia (2014). El vuelo de la esperanza : el Proyecto de las Comunidades Especiales Puerto Rico, 1997-2004 [The flight of hope: the Special Communities Project Puerto Rico, 1997-2004] (in Spanish) (1st ed.). San Juan, Puerto Rico. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-9820806-1-0. OCLC 932293879.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Pasaporte: Voy Turisteando (in Spanish). Compañia de Turismo de Puerto Rico. 2021.

- ^ "Guayama inaugura la Ruta gastronómica de la Montaña". Primera Hora (in Spanish). November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ^ "Las 1,200 playas de Puerto Rico [The 1200 beaches of Puerto Rico]". Primera Hora (in Spanish). April 14, 2017. Archived from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- ^ Soto, Miladys (September 13, 2019). "Plaza Guayama se reinventa y se convierte en Céntrico". Metro. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Festivales, Eventos y Actividades en Puerto Rico". Puerto Rico Hoteles y Paradores (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Romero-Barcelo, Carlos. "Puerto Rico's Paso Fino Horse: The Epitome of Elegance in World Horsemanship". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ "El Deporte de Caballos de Paso Fino". EnciclopediaPR (in Spanish). October 12, 2020. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ Proximo juego local vs Quebradillas: 22 de abril de 2012. Accessed on 17 January 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Report of the Census of Porto Rico 1899". War Department Office Director Census of Porto Rico. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Table 3-Population of Municipalities: 1930 1920 and 1910" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Table 4-Area and Population of Municipalities Urban and Rural: 1930 to 1950" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ "Table 2 Population and Housing Units: 1960 to 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "PUERTO RICO: 2020 Census". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "El representante Luis "Narmito" Ortiz Lugo concede la victoria a O'brian Vázquez Molina". El Vocero de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). May 7, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Elecciones Generales 2012: Escrutinio General Archived 2013-01-15 at the Wayback Machine on CEEPUR

- ^ "Ley Núm. 70 de 2006 -Ley para disponer la oficialidad de la bandera y el escudo de los setenta y ocho (78) municipios". LexJuris de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "GUAYAMA". LexJuris (Leyes y Jurisprudencia) de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). February 19, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Delgado, Joe. "Guayama... El Pueblo de los Brujos". Link to Puerto Rico.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on December 22, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Delgado, Joe. "Guayama... Town Of Wizards". Link to Puerto Rico.com. Translated with assistance from George LaMontagne. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "ESCUELAS". Salon Hogar (in Spanish). Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2008.

- ^ Larsson, Björn; Zekira, David (January 29, 2015). "Aerovias NPR - Aerovias Nacionales Puerto Rico". Airline Timetable Images. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Guayama Bridges". National Bridge Inventory Data. US Dept. of Transportation. Archived from the original on February 21, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jorge (June 23, 2009). "Fallece primera actriz Gilda Galán" [First actress Gilda Galán dies]. El Vocero de Puerto Rico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

External links

edit- Official page of the Municipality of Guayama Archived August 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine (In Spanish)

- Official Tourism Page of Guayama (In Spanish)

- Historic Places in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, a National Park Service Discover