Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj (born May 26, 1974 in Taiz, Yemen), also known as Riyadh the Facilitator, is a Yemeni alleged Al-Qaeda associate who is currently being held in the United States' Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba.[3] He is accused of being a "senior al-Qaida facilitator who swore an oath of allegiance to and personally recruited bodyguards for Osama Bin Laden".[4]

| Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj | |

|---|---|

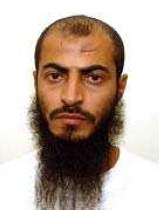

Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj official Guantanamo portrait, showing him wearing the white uniform issued to compliant captives. | |

| Born | May 26, 1974[1][2] Taiz, Yemen |

| Arrested | February 2002 Karachi, Pakistan |

| Detained at | CIA's black sites Guantanamo |

| ISN | 1457 |

| Status | Still held in Guantanamo |

Al-Hajj arrived at the Guantanamo detention camps on 20 September 2004, and has been held there for 20 years, 1 month and 15 days.[5][6]

Transportation to Guantanamo Bay

editHuman Rights group Reprieve reports that flight records show two captives named Al-Sharqawi and Hassan bin Attash were flown from Kabul in September 2002. The two men were flown aboard N379P, a plane suspected to be part of the CIA's ghost fleet. Flight records showed that the plane originally departed from Diego Garcia, stopped in Morocco, Portugal, then Kabul before landing in Guantanamo Bay.[7]

The Guardian reports that one of the two men has been released from US custody.[7]

A differing report shows al-Hajj was arrested by the CIA in Karachi, Pakistan, in February 2002, and rendered to Jordan. He was transferred to Afghanistan in January 2004, where he was held at the CIA-run Dark Prison, then at Bagram Air Base, and then finally transferred to Guantanamo in September 2004.[8]

Extraordinary rendition

editSharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj has written that after his capture, in February 2002, in Pakistan he spent two years in CIA custody in foreign interrogation centers, prior to his transfer to Guantanamo, in February 2004: [9][10] He writes that he spent 19 months in Amman, Jordan, and then five months in a secret interrogation center. While in Jordan he had been handed over to the custody of Jordan's General Intelligence Department. He wrote:

- I was kidnapped, not knowing anything of my fate, with continuous torture and interrogation for the whole of two years. When I told them the truth, I was tortured and beaten.

- I was told that if I wanted to leave with permanent disability both mental and physical, that that could be arranged. They said they had all the facilities of Jordan to achieve that. I was told that I had to talk, I had to tell them everything.

Official status reviews

editOriginally the Bush Presidency asserted that captives apprehended in the "war on terror" were not covered by the Geneva Conventions, and could be held indefinitely, without charge, and without an open and transparent review of the justifications for their detention.[11] In 2004 the United States Supreme Court ruled, in Rasul v. Bush, that Guantanamo captives were entitled to being informed of the allegations justifying their detention, and were entitled to try to refute them.

Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants

editFollowing the Supreme Court's ruling the Department of Defense set up the Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants.[11][14]

Scholars at the Brookings Institution, led by Benjamin Wittes, listed the captives still held in Guantanamo in December 2008, according to whether their detention was justified by certain common allegations.:[15]

- Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... are members of Al Qaeda."[15]

- Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... were at Tora Bora."[15]

- Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... served on Osama Bin Laden’s security detail."[15]

- Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj was listed as one of the captives who was a member of the "al Qaeda leadership cadre".[15]

- Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj was listed as one of the "82 detainees made no statement to CSRT or ARB tribunals or made statements that do not bear materially on the military’s allegations against them."[15]

Habeas Corpus

editIn June 2011, a federal Judge ruled that the Obama administration can not use certain statements al-Hajj gave to justify his detention because the government did not rebut claims of torture in Jordan and Afghanistan. But the same judge rejected a defense attempt to suppress an incriminating statement al-Hajj made before his claims of torture.[16]

Formerly secret Joint Task Force Guantanamo assessment

editOn 25 April 2011, whistleblower organization WikiLeaks published formerly secret assessments drafted by Joint Task Force Guantanamo analysts.[17][18] His 11-page Joint Task Force Guantanamo assessment was drafted on 20 July 2008.[19] It was signed by camp commandant Rear Admiral David M Thomas Jr. He recommended continued detention.

Joint Review Task Force

editWhen he assumed office in January 2009, President Barack Obama made a number of promises about the future of Guantanamo.[20][21][22] He promised to institute a new review system. That new review system was composed of officials from six departments, where the OARDEC reviews were conducted entirely by the Department of Defense. When it reported back, a year later, the Joint Review Task Force classified some individuals as too dangerous to be transferred from Guantanamo, even though there was no evidence to justify laying charges against them. On 9 April 2013, that document was made public after a Freedom of Information Act request.[23] Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj was one of the 71 individuals deemed too innocent to charge, but too dangerous to release. Al-Hajj was approved for transfer on 8 June 2021.[24]

References

edit- ^ "JTF- GTMO Detainee Assessment". Department of Defense. Retrieved 21 March 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Guantanamo Detainee Assessment" (PDF). Department of Defense. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ OARDEC. "List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2006. Works related to List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through 15 May 2006 at Wikisource

- ^ "JTF-GTMO Detainee Assessment" (PDF). therenditionproject.org.uk.

- ^ "Measurements of Heights and Weights of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (ordered and consolidated version)" (PDF). humanrights.ucdavis.edu, from DoD data. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2010.

- ^ Margot Williams (3 November 2008). "Guantanamo Docket: Abdu Ali al Haji Sharqawi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ a b

Richard Norton-Taylor, Duncan Campbell (10 March 2008). "Fresh questions on torture flights spark demands for inquiry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

Flight plan records show that one of the aircraft, registered N379P, flew in September 2002 from Diego Garcia to Morocco. From there it flew to Portugal and then to Kabul. Passenger names have been blacked out. However, Reprieve, which represents prisoners faced with the death penalty and torture, said that in Kabul the aircraft picked up Al-Sharqawi and Hassan bin Attash, two suspects who were tortured in Jordan before being rendered to Afghanistan and flown to Guantánamo Bay. Those rendered through Diego Garcia remain unidentified. In a letter to Miliband, Clive Stafford Smith, Reprieve's legal director, said: 'It is certainly not going to rebuild public confidence if we say that two people were illegally taken through British territory but then refuse to reveal the fates of these men.'

- ^

"Human Rights Watch, Double Jeopardy: CIA Renditions to Jordan (2008)". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Craig Whitlock (2 December 2007). "Non-Jordanian suspects sent by CIA to Amman spy center". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Mariner, Joanne (10 April 2008). "We'll make you see death". Salon magazine. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ^ a b

"U.S. military reviews 'enemy combatant' use". USA Today. 11 October 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007.

Critics called it an overdue acknowledgment that the so-called Combatant Status Review Tribunals are unfairly geared toward labeling detainees the enemy, even when they pose little danger. Simply redoing the tribunals won't fix the problem, they said, because the system still allows coerced evidence and denies detainees legal representation.

- ^ Guantánamo Prisoners Getting Their Day, but Hardly in Court Archived 26 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 11 November 2004 - mirror Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Inside the Guantánamo Bay hearings: Barbarian "Justice" dispensed by KGB-style "military tribunals" Archived 9 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, 11 December 2004

- ^

"Q&A: What next for Guantanamo prisoners?". BBC News. 21 January 2002. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d e f Benjamin Wittes; Zaathira Wyne (16 December 2008). "The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study" (PDF). The Brookings Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ^

Tim Hull (8 June 2011). "Gitmo Detainee Seals Up Torture Confessions". courthousenews.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

Next he was transferred to a so-called "dark prison" in Kabul, Afghanistan, according to a recently unsealed ruling in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

- ^

Christopher Hope; Robert Winnett; Holly Watt; Heidi Blake (27 April 2011). "WikiLeaks: Guantanamo Bay terrorist secrets revealed -- Guantanamo Bay has been used to incarcerate dozens of terrorists who have admitted plotting terrifying attacks against the West – while imprisoning more than 150 totally innocent people, top-secret files disclose". The Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

The Daily Telegraph, along with other newspapers including The Washington Post, today exposes America's own analysis of almost ten years of controversial interrogations on the world's most dangerous terrorists. This newspaper has been shown thousands of pages of top-secret files obtained by the WikiLeaks website.

- ^ "WikiLeaks: The Guantánamo files database". The Telegraph (UK). 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ "Sharqawi Abdu Ali Al Hajj: Guantanamo Bay detainee file on Sharqawi Abdu Ali Al Hajj, PK9YM-001457DP, passed to the Telegraph by Wikileaks". The Telegraph (UK). 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Peter Finn (22 January 2010). "Justice task force recommends about 50 Guantanamo detainees be held indefinitely". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ Peter Finn (29 May 2010). "Most Guantanamo detainees low-level fighters, task force report says". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ Andy Worthington (11 June 2010). "Does Obama Really Know or Care About Who Is at Guantánamo?". Archived from the original on 16 June 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- ^ "71 Guantanamo Detainees Determined Eligible to Receive a Periodic Review Board as of April 19, 2013". Joint Review Task Force. 9 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Unclassified summary of final determination" (PDF). Department of Defense. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

External links

edit- Judge Rules Yemeni’s Detention at Guantánamo Based Solely on Torture Andy Worthington

- Human Rights Watch, Double Jeopardy: CIA Renditions to Jordan (2008)

- UN Secret Detention Report (Part Three): Proxy Detention, Other Countries’ Complicity, and Obama’s Record Andy Worthington

- Gitmo Detainee Seals Up Torture Confessions 8 June 2011