Muchiri (IPA: [mutːʃiɾi]), commonly anglicized as Muziris (Ancient Greek: Μουζιρίς,[2] Old Malayalam: Muciri or Muciripattanam[3] possibly identical with the medieval Muyirikode[4]) was an ancient harbour[5] and an urban centre on the Malabar Coast.[3] Muziris found mention in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, the bardic Tamil poems and a number of classical sources.[6][7][8][9] It was the major ancient port city of Cheras. The exact location of Muziris has been a matter of dispute among historians and archaeologists. However, excavations since 2004 at Pattanam in Ernakulam district of Kerala have led some experts to suggesting the hypothesis that the city was located just there.[1][8][3] It was an important trading port for Christian and Muslim merchants arriving from other countries.

Muciri | |

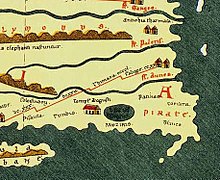

Muziris, as shown in the 4th century Tabula Peutingeriana | |

| Alternative name | Muyirikkode |

|---|---|

| Location | Pattanam, Kerala, India[1] |

| Region | Chera Kingdom |

| Type | Settlement |

Muziris was a key to the interactions between South India and Persia, the Middle East, North Africa, and the (Greek and Roman) Mediterranean region.[10][11] Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, hailed Muziris as "the first emporium of India".[3] The important known commodities exported from Muziris were spices (such as black pepper and malabathron), semi-precious stones (such as beryl), pearls, diamonds, sapphires, ivory, Chinese silk, Gangetic spikenard and tortoise shells. The Roman navigators brought gold coins, peridots, thin clothing, figured linens, multicoloured textiles, sulfide of antimony, copper, tin, lead, coral, raw glass, wine, realgar and orpiment.[12][13] The locations of unearthed coin-hoards from Pattanam suggest an inland trade link from Muziris via the Palghat Gap and along the Kaveri Valley to the east coast of India. Though the Roman trade declined from the 5th century AD, the former Muziris attracted the attention of other nationalities, particularly the Persians, the Chinese and the Arabs, presumably until the devastating floods of Periyar in 1341.[7][3]

Earlier Muziris was identified with the region around Mangalore in southwestern Karnataka.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] Later hypothesis was that it was situated around present day Kodungallur, a town and Taluk in Thrissur district.[24] Kodungallur in central Kerala figures prominently in the ancient history of southern India from the second Chola period as a hub of the Chera rulers.[25] But later, a series of excavations were conducted at the village of Pattanam in between North Paravoor and Kodungallur by Kerala Council for Historical Research (an autonomous institution outsourced by the Kerala State Department of Archaeology) in 2006-07 and it was announced that the lost "port" of Muziris was found and started the new hypothesis.[8][26][27] This identification of Pattanam as the ancient Muziris also sparked controversy among historians.[28]

As per texts, Kerala is known to have traded spices since the Sangam era; it is based on this trade that some historians have implied that only foreign countries needed spices (pepper). Some historians and archaeologists criticized this view starting a debate among historians of South India.[29][30][31]

Etymology

editThe derivation of the name "Muziris" is said to be from the native name of the port, "Muciri" (Malayalam: മുചിറി). In the region, the Periyar river perhaps branched into two like a cleft lip, thus speculatively leading to the name "Muciri". It is frequently referred to as Muciri in Sangam poems, Muracippattanam in the Sanskrit epic Ramayana,[32][33] and as Muyirikkottu in the Jewish copper plate of an 11th-century Chera ruler.

Early descriptions

editSangam literature

editA tantalizing description of Muziris is in Akanaṉūṟu, an anthology of early Tamil bardic poems (poem number 149.7-11) in Eṭṭuttokai[34]

the city where the beautiful vessels, the masterpieces of the Yavanas [Ionians], stir white foam on the Culli [Periyar], a river of the Chera, arriving with gold and departing with pepper-when that Muciri, brimming with prosperity, was besieged by the din of war.

The Purananuru described Muziris as a bustling port city where interior goods were exchanged for imported gold.[35][36] It seems that the Chera chiefs regarded their contacts with the Roman traders as a form of gift exchange rather than straightforward commercial dealings.[37]

With its streets, its houses, its covered fishing boats, where they sell fish, where they pile up rice-with the shifting and mingling crowd of a boisterous river-bank, where the sacks of pepper are heaped up-with its gold deliveries, carried by the ocean-going ships and brought to the river bank by local boats, the city of the gold-collared Kuttuvan (Chera chief), the city that bestows wealth to its visitors indiscriminately, and the merchants of the mountains, and the merchants of the sea, the city where liquor abounds, yes, this Muciri, were the rumbling ocean roars, is given to me like a marvel, a treasure. .

Akananuru describes Pandya attacks on the Chera port of Muciri. This episode is impossible to date, but the attack seems to have succeeded in diverting Roman trade from Muziris.[37]

It is suffering like that experienced by the warriors who were mortally wounded and slain by the war elephants. The suffering that was seen when the Pandya prince came to besiege the port of Muciri on his flag-bearing chariot with decorated horses

Riding on his great and superior war elephant the Pandya prince has conquered in battle. He has seized the sacred images after winning the battle for rich Muciri.

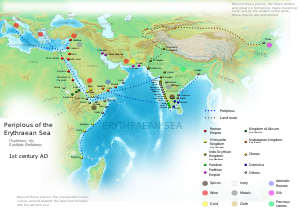

Navigation of the Red Sea

editThe author of the Greek travel book Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century AD) gives an elaborate description of the Chera Kingdom.[38][39]

...then come Naura and Tyndis, the first markets of Lymrike, and then Muziris and Nelkynda, which are now of leading importance. Tyndis is of the Kingdom of Cerobothra; it is a village in plain sight by the sea. Muziris, in the same Kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by the river and sea 500 stadia, and up the river from the shore 20 stadia...

There is exported pepper, which is produced in only one region near these markets, a district called Cottonara.

The Periplus reveals how Muziris became the main trade port for the Chera chiefdom. The author explains that this large settlement owed its prosperity to foreign commerce, including shipping arriving from northern India and the Roman empire. Black pepper from the hills was brought to the port by the local producers and stacked high in warehouses to await the arrival of Roman merchants. As the shallows at Muziris prevented deep-hulled vessels from sailing upriver to the port, Roman freighters were forced to shelter at the edge of the lagoon while their cargoes were transferred upstream on smaller craft.[37]

The Periplus records that special consignments of grain were sent to places like Muziris and scholars suggest that these deliveries were intended for resident Romans who needed something to supplement the local diet of rice.[37]

Pliny the Elder

editPliny the Elder gives a description of voyages to India in the 1st century AD. He refers to many Indian ports in his The Natural History.[40] However, by the time of Pliny, Muziris was no longer a favoured location in Roman trade dealing with South India.[41]

To those who are bound for India, Ocelis (on the Red Sea) is the best place for embarkation. If the wind, called Hippalus (south-west Monsoon), happens to be blowing it is possible to arrive in forty days at the nearest market in India, Muziris by name. This, however, is not a very desirable place for disembarkation, on account of the pirates which frequent its vicinity, where they occupy a place called Nutrias; nor, in fact, is it very rich in articles of merchandise. Besides, the road stead for shipping is a considerable distance from the shore, and the cargoes have to be conveyed in boats, either for loading or discharging. At the moment that I am writing these pages, the name of the King of this place is Celebothras.

Claudius Ptolemy

editPtolemy placed the Muziris emporium north of the mouth of the Pseudostomus river in his Geographia.[42] Pseudostomus (literally, "false mouth", in Greek) is generally identified with the modern-day Periyar River.

Muziris papyrus

editThis Greek papyrus of the 2nd century AD documents a contract involving an Alexandrian merchant importer and a financier that concerns cargoes, especially of pepper and spices from Muziris.[43] The fragmentary papyrus records details about a cargo consignment (valued at around nine million sesterces) brought back from Muziris on board a Roman merchant ship called the Hermapollon. The discovery opened a strong base to ancient international and trade laws in particular and has been studied at length by economists, lawyers, and historians.[44][45]

Cilappatikaram

editThe great Tamil epic Cilappatikaram (The Story of the Anklet) written by Ilango Adigal, a Jain poet-prince from Kodungallur (Muziris) during the 2nd century A.D., described Muziris as a place where Greek traders would arrive in their ships to barter their gold to buy pepper, and since barter trade is time-consuming, they lived in homes living a lifestyle that he termed as "exotic" and a source of "local wonder".[46][47][48]

Concerning Muziris and the Roman spice trade with Malabar, the Cilappatikaram describes the prevailing situation as follows:[48]

When the broadrayed sun ascends from the south and white clouds start to form in the early cool season, it is time to cross the dark, billowing ocean. The rulers of Tyndis dispatch vessels loaded with eaglewood, silk, sandalwood, spices and all sorts of camphor.

Peutinger's Map

editPeutinger Map, is an odd-sized medieval copy of an ancient Roman road map, "with information which could date back to 2nd century AD", in which both Muziris and Tondis are well marked, "with a large lake indicated behind Muziris, and besides which is an icon marked Templ(um) Augusti, widely taken to mean a “Temple of Augustus".[49] A large number of Roman subjects must have spent months in this region awaiting favourable conditions for return sailings to the Empire. This could explain why the Map records the existence of an Augustan temple.[37] It is also possible that there was a Roman colony in Muziris.[50]

Great "floods" of Periyar

editMuziris disappeared from every known map of antiquity, and without a trace, presumably because of a cataclysmic event in 1341, a "cyclone and floods" in the Periyar that altered the geography of the region. The historians Rajan Gurukkal and Dick Whittakker say in a study titled "In Search of Muziris" that the event, which opened up the present harbour at Kochi and the Vembanad backwater system to the sea and formed a new deposit of land now known as the Vypin Island near Kochi, "doubtless changed access to the Periyar river, but geologically it was only the most spectacular of the physical changes and land formation that have been going on [there] from time immemorial". According to them, for example, a geophysical survey of the region has shown that 200–300 years ago the shoreline lay about three kilometres east of the present coast and that some 2,000 years earlier it lay even further east, about 6.5 km inland. "If Muziris had been situated somewhere here in Roman times, the coast at that time would have run some 4-5 km east of its present line. The regular silting up of the river mouth finally forced it to cease activity as a port."[25]

Archaeological excavations

editA series of excavations conducted at Kodungallur starting from 1945, yielded nothing that went back to before the 13th century. Another excavation was carried out in 1969 by the Archaeological Survey of India at Cheraman Parambu, 2 km north of Kodungallur. Only antiquities of the 13th and 16th century were recovered.[51]

In 1983, a large hoard of Roman coins was found at a site around six miles from Pattanam. A series of pioneering excavations from 2007 carried out by the Kerala Council for Historical Research (KCHR, an autonomous institution) at Pattanam uncovered a large number of artifacts.[52][53][54][55][56] So far, seven seasons of excavations (2007–14) have been completed by KCHR at Pattanam.[57]

The identification of Pattanam as Muziris is a divisive subject among some historians of South India. When KCHR announced the possible finding of Muziris based on Pattanam finds, it invited criticism from historians and archaeologists. Historians such as R Nagaswamy, KN Panikkar and MGS Narayanan disagreed with the identification and called for further analysis.[30][49][56] "Whether Pattanam was Muziris is not of immediate concern to us", the chief of the Kerala Council for Historical Research recently stated to the media.[58] Yet, even the last field report on the excavations (2013) explicitly marks Pattanam as Muziris.[59]

While historian and academic Rajan Gurukkal has spoken in favour of the 'salvage of historic relics at Pattanam' by KCHR given the site's disturbance due to continual human habitation and activity, he thinks it [ancient Muziris] was no more than a colony of merchants from the Mediterranean. "The abundance of material from the Mediterranean suggests that traders arrived here using favorable monsoon winds and returned using the next after short sojourns," he says. Feeder vessels transported them between their ships and the wharf, but it would be incorrect to say that it was a sophisticated port in an urban setting. The place did not have any evolved administration nor any sophistication. "I believe it [Pattanam] was Muziris. Had it been elsewhere, Pattanam wharf and colony would’ve found a mention in available records," he says.[60]

Discoveries from Pattanam

editArchaeological research has shown that Pattanam was a port frequented by Romans and it has a long history of habitation dating back to 10th century BC. Its trade links with Rome peaked between 1st century BC and 4th century AD.[61]

A large quantity of artifacts represents the maritime contacts of the site with the Mediterranean, Red Sea and Indian Ocean rims. Major finds include ceramics, lapidary-related objects, metal objects, coins, architectural ruins, geological, zoological and botanical remains.[59]

- Mediterranean: (100 BCE to CE 400) Amphora, terra sigillata shards, Roman glass fragments and gaming counters.

- West Asian, South Arabian & Mesopotamian: (300 BCE to CE 1000) Turquoise glazed pottery, torpedo jar fragments and frankincense crumbs.

- Chinese: (CE 1600 to CE 1900) Blue on white porcelain shards.

- Regional/Local: (1000 BCE to CE 2000) Black and red ware shards, Indian rouletted ware, gemstones, glass beads, semi precious stone beads/inlays/intaglio, cameo–blanks, coins, spices, pottery and terracotta objects.

- Urban life: (100 BCE to CE 400) burnt bricks, rooftiles, ring-wells, storage jars, toilet features, lamps, coins, stylus, personal adornment items and scripts on pottery.

- Industrial character: (100 BCE to CE 400) Metallurgy reflected in iron, copper, gold and lead objects, crucibles, slag, furnace installations, lapidary remains of semi-precious stones and spindle whorls indicating weaving.

- Maritime features: (100 BCE to CE 400) Wharf, warehouse, canoe, bollards.

The major discoveries from Pattanam include thousands of beads (made of semi-precious stone), shards of Roman amphora, Chera-era coins made of copper alloys and lead, fragments of Roman glass pillar bowls, terra sigillata, remains of a long wooden boat and associated bollards made of teak and a wharf made of fired brick.[12][62]

The most remarkable find at Pattanam excavations in 2007 was a brick structural wharf complex, with nine bollards to harbour boats and in the midst of this, a highly decayed canoe, all perfectly mummified in mud. The canoe (6 meters long) was made of Artocarpus hirsutus, a tree common on the Malabar Coast, out of which boats are made.[63] The bollards, some of which are still in satisfactory condition, were made of teak.[64]

Three Tamil-Brahmi scripts were also found in the Pattanam excavations. The last Tamil-Brahmi script (dated to c. 2nd century AD, probably reading "a-ma-na", meaning "a Jaina" in Malayalam) was found on a pot-rim at Pattanam. If the rendering and the meaning is not mistaken, it establishes that Jainism was prevalent on the Malabar Coast at least from the 2nd century. This is the first time that excavators have found evidence relating to a religious system in ancient Kerala.[65]

DNA-analyses of skeleton samples discovered from Pattanam confirmed the presence of people with West Eurasian genetic imprints in Muziris in the past. This is considered to be an indication of the huge international importance the ancient port-city once held in the past.[66] However, the ASI was more sceptical, suggesting that more research is required to confirm the Eurasian presence in the site.[67]

Muziris Heritage Project

editThe Muziris Heritage Project is a tourism venture by Tourism Department of Kerala to reinstate the historical and cultural significance of Muziris. The idea of the project came after the extensive excavations and discoveries at Pattanam by the Kerala Council for Historical Research.[68] The project also covers various other historically significant sites and monuments in central Kerala.

The nearby site of Kottappuram, a 16th-century fort, was also excavated (from May 2010 onwards) as part of the Muziris Heritage Project.[69]

See also

edit- Kottayil Kovilakam

- Kochi-Muziris Biennale – an international exhibition of contemporary art held in Kochi, Kerala.

References

edit- ^ a b Muthiah, S. (24 April 2017). "The ancient ports of India". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 53 and 54

- ^ a b c d e "Lost cities #3 – Muziris: did black pepper cause the demise of India's ancient port? | Cities | The Guardian". theguardian.com. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ A. Sreedhara Menon (1967). "Muchiri - A Survey of Kerala History". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Gurukkal, Rajan (29 June 2013). "A Misnomer in Political Economy: Classical Indo-Roman Trade". Economic & Political Weekly. 48 (26–27). Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ "Artefacts from the lost Port of Muziris." The Hindu. 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Muziris, at last?" R. Krishnakumar, www.frontline.in Frontline, 10–23 April 2010.

- ^ a b c "Pattanam richest Indo-Roman site on Indian Ocean rim." The Hindu. 3 May 2009.

- ^ George Menachery; Werner Chakkalakkal (10 January 2001). "Cranganore: Past and Present". Kodungallur – The Cradle of Christianity in India. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Cyclopaedia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia. Ed. by Edward Balfour (1871), Second Edition. Volume 2. p. 584.

- ^ "Search for India's ancient city". bbc.co.uk BBC World News, 11 June 2006. Web [1]

- ^ a b Steven E. Sidebotham. Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route, pp 191. University of California Press 2011

- ^ George Gheverghese Joseph (2009). A Passage to Infinity. New Delhi: SAGE Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 13. ISBN 978-81-321-0168-0.

- ^ J. Sturrock (1894). Madras District Manuals - South Canara (Volume-I). Madras Government Press.

- ^ Harold A. Stuart (1895). Madras District Manuals - South Canara (Volume-II). Madras Government Press.

- ^ Government of Madras (1905). Madras District Gazetteers: Statistical Appendix for South Canara District. Madras Government Press.

- ^ Government of Madras (1915). Madras District Gazetteers South Canara (Volume-II). Madras Government Press.

- ^ William Logan (1887). Malabar Manual (Volume-I). Madras Government Press.

- ^ William Logan (1887). Malabar Manual (Volume-II). Madras Government Press.

- ^ Charles Alexander Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I). Madras Government Press.

- ^ Charles Alexander Innes (1915). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-II). Madras Government Press.

- ^ C. Achutha Menon (1911). The Cochin State Manual. Cochin Government Press.

- ^ Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 978-81-264-1588-5. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Romila Thapar. There is no mention of Trade via Sea-Route or of any ports during Sangam era. It were the Vikings who created first of ships which could cross sea, let alone ocean. The Scanidinavians used their ships to cross the sea and reach nearby countryside in Europe, and all that happened in early 12th century. The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. pp 46, Penguin Books India, 2003

- ^ a b Krishnakumar, P. "Muziris, at last?". www.frontline.in Frontline, 10–23 April 2010. Web. [2]

- ^ Basheer, K. P. M. "Pattanam finds throw more light on trade". The Hindu [Madras]. 12 June 2011. Web. [3]

- ^ Smitha, Ajayan. "Traces of controversies". Deccan Chronicle. 20 Feb. 2013. Web. [4]

- ^ "Expert nails false propaganda on Muziris". newindianexpress.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Historian cautions on Pattanam excavations". The Hindu [Madras]. 6 February 2012. Web. [5]

- ^ a b "Archaeologist calls for excavations at Kodungalloor". The Hindu [Madras]. 5 August 2011. Web. [6]

- ^ "KCHR asked to hand over Pattanam excavation". ibnlive.in.com CNN-IBN, 16 November 2011. Web. [7]

- ^ "Muziris heritage project - history". Kerala Tourism.

- ^ Gantzer, Hugh & Colleen (2 December 2010). "Muziris: Bustling heart of the Malabar spice coast". The Economic Times.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32919-1.

- ^ Peter Francis. Asia's Maritime Bead Trade: 300 B.C. to the Present, pp. 120 University of Hawaii Press, 01-Jan-2002

- ^ Menachery, George; Azhikode-Kodungallur (1987). Kodungallur City of St. Thomas.

- ^ a b c d e Raoul McLaughlin. Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. pp 48-50, Continuum (2010)

- ^ "The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea". depts.washington.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Martin, K. a; Anandan, S.; Martin, K. a; Anandan, S. (21 January 2012). "Re-enact Muziris voyages, KHA tells Navy". The Hindu. Retrieved 23 April 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- ^ "Philemon Holland's Pliny". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, vi.(26).104.

- ^ Peter Francis. Asia's Maritime Bead Trade: 300 B.C. to the Present, pp. 119 University of Hawaii Press, 01-Jan-2002

- ^ Romila Thapar. The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Penguin Books India, 2003

- ^ Raoul McLaughlin. Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. pp 40, Continuum (2010)

- ^ For the full text in Greek and its translation, see http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/ifa/zpe/downloads/1990/084pdf/084195.pdf

- ^ Madhukar, Jayanthi (3 December 2016). "Malayala panorama". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (24 April 2017). "The ancient ports of India". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, Raoul (11 September 2014). The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473840959.

- ^ a b "Navigation News - Frontline". FRONTLINE. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Romans in Muziris

- ^ Srivathsan, A. "In search of Muziris". The Hindu [Madras]. 2 May 2010. Web. [8]

- ^ "Search for India's ancient city". BBC News. 11 June 2006. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ Govind, M. Harish (23 March 2004). "Archaeologists stumble upon Muziris". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- ^ "Hunting for Muziris". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 March 2004. Archived from the original on 27 May 2004.

- ^ "Excavations highlight Malabar maritime heritage". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008.

- ^ a b Rajagopal, Shyama; Surendranath, Nidhi (30 August 2013). "Archaeology Dept. lumbering under shortage of manpower". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ^ Srivathsan, A. (22 May 2013). "Pattanam antiquity authenticated by radiocarbon dating". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ^ S. ANANDAN Was Pattanam an urban trade centre? 28 May 2014 The Hindu [9]

- ^ a b "KCHR Pattanam Seventh Season Handbook" (PDF). keralahistory.ac.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Kerala historians at loggerheads over archaeological findings at Pattanam KOCHI, 28 May 2014 The Hindu [10]

- ^ Oxford University to join Pattanam excavations THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, 25 December 2013 The Hindu [11]

- ^ "Excavations highlight Malabar maritime heritage". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008.

- ^ KCHR reports 2007. P.J. Cherian et al.

- ^ Chambers, W. 1875. Chambers's Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. London. p. 513.

- ^ Subramanian, T. S. (14 March 2011). "Tamil-Brahmi script found at Pattanam in Kerala". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- ^ "Ancient DNA research confirms West Eurasian genetic imprints in Pattanam". English.Mathrubhumi. 29 April 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ ANI (29 April 2023). "One or two DNA samples will not give us entire idea: ASI on DNA research showing Eurasian imprints in Kerala". ThePrint. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Introduction". www.keralatourism.org Kerala Tourism

- ^ "Exhibition on Kottappuram Fort excavations" THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, 16 December 2010 'The Hindu' [12]