The Great Fire of New York was a devastating fire that burned through the night of September 20, 1776, and into the morning of September 21, on the West Side of what then constituted New York City at the southern end of the island of Manhattan.[3] It broke out in the early days of the military occupation of the city by British forces during the American Revolutionary War.

| Part of the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War | |

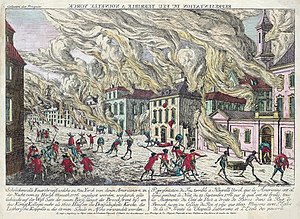

A contemporaneous artist's interpretation of the fire, published in 1776 | |

| Date | September 21, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Location | New York City |

| Outcome | 400 – 1,000 structures destroyed[1][2] |

The fire destroyed from 10 to 25 percent of the buildings in the city, while some unaffected parts of the city were plundered. Many people believed or assumed that one or more people deliberately started the fire, for a variety of different reasons. British leaders accused revolutionaries acting within the city and state, and many residents assumed that one side or the other had started it. The fire had long-term effects on the British occupation of the city, which did not end until 1783.

Background

editThe American Revolutionary War began in April 1775. The city of New York was already an important center of business but had not yet become a sprawling metropolis. It occupied only the lower portion of the island of Manhattan and had a population of approximately 25,000.[4] Before the war began, the Province of New York was politically divided, with active Patriot organizations and a colonial assembly that was strongly Loyalist.[5] After the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Patriots seized control of the city and began arresting and expelling Loyalists.[6]

Early in the summer of 1776, when the war was still in its early stages, British General William Howe embarked on a campaign to gain control of the city and its militarily important harbor. After occupying Staten Island in July, he launched a successful attack on Long Island in late August, assisted by naval forces under the command of his brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe.[7] American General George Washington recognized the inevitability of the capture of New York City, and withdrew the bulk of his army about 10 miles (16 km) north to Harlem Heights.[8] Several people, including General Nathanael Greene and New York's John Jay, advocated burning the city down to deny its benefits to the British.[9] Washington laid the question before the Second Continental Congress, which rejected the idea: "it should in no event be damaged."[10]

On September 15, 1776, British forces under Howe landed on Manhattan.[11] The next morning, some British troops marched toward Harlem, where the two armies clashed again, while others marched into the city.[12]

A civilian exodus from the city had begun well before the British fleet arrived in the harbor. The arrival the previous February of the first Continental Army troops in the city had prompted some people to pack up and leave,[13] including Loyalists who were specifically targeted by the army and Patriots.[14] The capture of Long Island only accelerated the abandonment of the city. During the Continental Army's occupation of the city, many abandoned buildings were appropriated for the army's use.[15] When the British arrived in the city, the property of Patriots was similarly appropriated for the use of the British Army.[16] Despite this, housing and other demands of the military occupation significantly strained the city's available building stock.[17]

Fire

editAccording to the eyewitness account of John Joseph Henry, an American prisoner aboard HMS Pearl, the fire began in the Fighting Cocks Tavern, near Whitehall Slip.[1] Abetted by dry weather and strong winds, the flames spread north and west, moving rapidly among tightly packed homes and businesses. Residents poured into the streets, clutching what possessions they could, and found refuge on the grassy town commons (today, City Hall Park). The fire crossed Broadway near Beaver Street and then burned most of the city between Broadway and the Hudson River.[18] The fire raged into the daylight hours and was stopped by changes in wind direction as much as by the actions of some of the citizenry and British marines sent in aid of the inhabitants.[1] It may also have been stopped by the relatively undeveloped property of King's College, located at the northern end of the fire-damaged area.[18][19] Estimates for the number of buildings destroyed range from 400 to 1,000, representing between 10 and 25 percent of the 4,000 city buildings in existence at the time.[1][2] Among the buildings destroyed was Trinity Church; St. Paul's Chapel survived.[19]

Suspicions of arson

editHowe's report to London implied that the fire was deliberately set: "a most bad attempt was made by a number of wretches to burn the town."[19] Royal Governor William Tryon suspected that Washington was responsible, writing that "many circumstances lead to conjecture that Mr. Washington was privy to this villainous act" and that "some officers of his army were found concealed in the city."[20] Many Americans also assumed that the fire was the work of Patriot arsonists. John Joseph Henry recorded accounts of marines returning to the Pearl after fighting the fire in which men were "caught in the act of firing the houses."[21]

Some Americans accused the British of setting the fire so that the city might be plundered. A Hessian major noted that some who fought the blaze managed to "pay themselves well by plundering other houses near by that were not on fire."[21]

Washington wrote to John Hancock on September 22, specifically denying knowledge of the fire's cause.[21] In a letter to his cousin Lund, Washington wrote, "Providence—or some good honest fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves".[22]

According to historian Barnet Schecter, no accusation of arson has withstood scrutiny. The strongest circumstantial evidence in favor of arson theories is the fact that the fire appeared to start in multiple places. However, contemporary accounts explain that burning debris from wooden roof shingles spread the fire. One diarist wrote that, "the flames were communicated to several houses" by the debris "carried by the wind to some distance."[20]

The British interrogated more than 200 suspects, but no charges were ever filed.[20] Coincidentally, Nathan Hale, an American captain engaged in spying for Washington, was arrested in Queens the day the fire started. Rumors attempting to link him to the fires have never been substantiated; there is nothing indicating that he was arrested (or eventually hanged) for anything other than espionage.[23]

Effect on British occupation

editMajor General James Robertson confiscated surviving uninhabited homes of known Patriots and assigned them to British officers. Churches, other than the state churches (Church of England) were converted into prisons, infirmaries, or barracks. Some of the common soldiers were billeted with civilian families. There was a great influx of Loyalist refugees into the city resulting in further overcrowding, and many of these returning and additional Loyalists from patriot-controlled areas encamped in squalid tent cities on the charred ruins. The fire convinced the British to put the city under martial law rather than returning it to civilian authorities. Crime and poor sanitation were persistent problems during the British occupation, which did not end until they evacuated the city on November 25, 1783.[24][25]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d Chester, p. 204

- ^ a b Trevelyan, p. 310

- ^ Stokes (1915–1928), v. 5, pp. 1020–24.

- ^ Schecter, p. 64

- ^ Schecter, pp. 50–51

- ^ Schecter, pp. 52–53

- ^ Johnston, pp. 94–224

- ^ Johnston, p. 228

- ^ Johnston, p. 229

- ^ Johnston, p. 230

- ^ Schecter, pp. 179–193

- ^ Johnston, p. 245

- ^ Schecter, pp. 71–72

- ^ Schecter, p. 96

- ^ Schecter, p. 90

- ^ Schecter, p. 194

- ^ Schecter, p. 209

- ^ a b Lamb, p. 135

- ^ a b c Chester, p. 205

- ^ a b c Schecter, p. 206

- ^ a b c Schecter, p. 207

- ^ Schecter, p. 208

- ^ Schecter, pp. 210–215

- ^ Schecter, pp. 275–276

- ^ Lamb, p. 274

References

edit- Johnston, Henry Phelps (1878). The campaign of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn. Brooklyn: The Long Island Historical Society. p. 245. OCLC 234710.

citizens.

- Lamb, Martha Joanna (1896). History of the City of New York: The Century of National Independence, Closing in 1880. New York: A. S. Barnes. OCLC 7932050.

- Schecter, Barnet (2002). The Battle for New York. New York: Walker & Co. ISBN 0-8027-1374-2.

- Stokes, Isaac Newton Phelps (1915–1928). The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909. Robert H. Dodd.

- Trevelyan, Sir George Otto (1903). The American Revolution: 1766–1776. London, New York: Longmans, Green. p. 310. OCLC 8978164.

40°42′11″N 74°00′47″W / 40.70306°N 74.01306°W