The Glyndŵr rebellion was a Welsh rebellion led by Owain Glyndŵr against the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages. During the rebellion's height between 1403 and 1406, Owain exercised control over the majority of Wales after capturing several of the most powerful English castles in the country, and formed a parliament at Machynlleth. The revolt was the last major manifestation of Welsh independence before the annexation of Wales into England in 1543.

| Glyndŵr rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

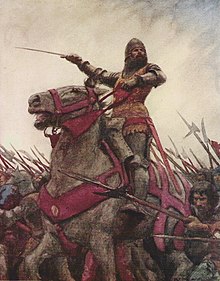

Owain Glyndŵr by A. C. Michael, 1918 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Principality of Wales Kingdom of France (until 1408) | Kingdom of England | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Owain Glyndŵr Sir Edmund Mortimer † Rhys Gethin † Gruffudd ab Owain Glyndŵr (POW) Tudur ap Gruffudd † Jean II de Rieux |

King Henry IV (1400–1413) King Henry V (1413–1415) John Talbot Richard Grey Dafydd Gam | ||||||

The uprising began in 1400, when Owain Glyndŵr, a descendant of several Welsh royal dynasties, claimed the title prince of Wales following a dispute with a neighbouring English lord. In 1404, after a series of successful castle sieges and battlefield victories, Owain was crowned prince of Wales in the presence of Scottish, French, Spanish and Breton envoys. He summoned a national parliament, where he announced plans to reintroduce the traditional Welsh laws of Hywel Dda, establish an independent Welsh church, and build two universities. Owain also formed an alliance with Charles VI of France, and in 1405 a French army landed in Wales to support the rebellion.

Early in 1406, Owain's forces suffered defeats at Grosmont and Usk, in the south east of Wales. Despite the initial successes of the rebellion from 1400–1406, the Welsh were severely outnumbered and the Welsh populace increasingly exhausted by an English blockade combined with pillaging and violence by English armies.

By 1407 the English had recaptured Anglesey and large parts of south Wales. In 1408 they seized Aberystwyth Castle, followed by Harlech Castle in February 1409, effectively ending Owain's territorial rule, although Owain himself was never captured or killed. He ignored two offers of a pardon from the new King Henry V and Welsh resistance continued in small pockets of the country for several more years utilising guerrilla tactics. Owain disappeared in 1415, when he was recorded to have died. His son, Maredudd ab Owain, accepted a pardon from King Henry V in 1421, formally ending the rebellion.

Background

editFall of Richard II

editIn the last decade of the 14th century, Richard II of England had launched a bold plan to consolidate his hold on his kingdom and break the power of the magnates who constantly threatened his authority. As part of this plan, Richard began to shift his power base from the southeast and London towards the county of Cheshire, and systematically built up his power in nearby Wales. Wales was ruled through a patchwork of semi-autonomous feudal states, bishoprics, shires, and territory under direct royal rule. Richard eliminated his rivals and took their land or gave it to his favourites. As he did so, he raised an entire class of Welsh people to fill the new posts created in his new fiefdoms. For these people, the final years of the reign of Richard II were full of opportunities. To the English magnates, it was a further sign that Richard was dangerously out of control.[1]

In 1399, the exiled Henry Bolingbroke, heir to the Duchy of Lancaster, returned to reclaim his lands. Henry raised an army and marched to meet the king.[2] Richard hurried back from Ireland to Wales to deal with Bolingbroke, but he was arrested by Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland as he was on his way from Conwy Castle to meet Bolingbroke at Flint Castle, supposedly to discuss the restitution of Henry's lands. Richard was imprisoned at the English border city of Chester before being taken to London. Parliament quickly made Henry Bolingbroke Regent and then King. Richard died in Pontefract Castle, shortly after the failed Epiphany Rising of English nobles in January 1400, but his death was not generally known for some time. In Wales, people like Owain Glyndŵr were asked for the first time in their life to decide their loyalties. The Welsh had generally supported King Richard,[3][better source needed] who had succeeded his father, Edward, the Black Prince, as Prince of Wales. With Richard removed, the opportunities for advancement for Welsh people became more limited. Many Welsh people seem to have been uncertain where this left them and their future.[citation needed]

For some time, supporters of the deposed king remained at large. On 10 January 1400 serious civil disorder broke out in Chester in support of the Epiphany Rising. An atmosphere of disorder was building along the Anglo-Welsh border.[citation needed]

Dispute between Owain Glyndŵr and de Grey

editThe revolt reportedly began as an argument with Owain Glyndŵr's English neighbour.[3][better source needed] Successive holders of the title Baron Grey de Ruthyn of Dyffryn Clwyd were English landowners in Wales. Glyndŵr had been engaged in a long-running land dispute with them.[4] He seems to have appealed to Parliament (though which one is not clear) to resolve the issue, with the courts under King Richard finding in his favour. Reginald Grey, 3rd Baron Grey de Ruthyn – loyal to the new king – then appears to have used his influence to have that decision overturned. Owain Glyndŵr possibly had his appeal rejected.[5] Another story is that de Grey deliberately withheld a Royal Summons for Glyndŵr to join the new king's Scottish campaign of August 1400. Technically, as a tenant-in-chief to the English king, Glyndŵr was obliged to provide troops, as he had done in the past.[6][7] By not responding to the hidden summons he seems, perhaps unwittingly, to have incurred Henry's wrath.

Welsh revolt, 1400–15

edit- Important battle

Castle garrisoned by English forces

Castle unsuccessfully besieged by Welsh forces

Castle possibly sacked by Welsh forces

Castle sacked or occupied by Welsh forces (dates held)

Welsh campaign of 1400

Welsh campaign of 1403

Franco-Welsh campaign of 1405

Possible route of 1405 campaign

- Important battle

On 16 September 1400, Owain acted, and was proclaimed Prince of Wales by a small band of followers who included his eldest son, his brothers-in-law, and the Dean of St Asaph.[8] This was a revolutionary statement in itself. Owain's men quickly spread through north-east Wales. On 18 September, the town of Ruthin and De Grey's stronghold of Ruthin Castle were attacked.[9] Denbigh, Rhuddlan, Flint, Hawarden, and Holt followed quickly afterward. On 22 September the town of Oswestry was badly damaged by Owain's raid. By 23 September Owain was moving south, attacking Powis Castle and sacking Welshpool.[10]

About the same time, the Tudur brothers from Anglesey launched a guerrilla war against the English. The Tudors of Penmynydd were a prominent Anglesey family who were closely associated with King Richard II. Gwilym ap Tudur and Rhys ap Tudur were both military leaders of a contingent of soldiers raised in 1396 to protect North Wales against any invasion by the French. They joined the king in his military expedition to Ireland in 1398. When Glyndŵr announced his revolt, Rhys, Gwilym and their third brother, Maredudd ap Tudur, openly swore allegiance; they were Glyndŵr's cousin on their mother's side.[11]

King Henry IV, on his way back from invading Scotland, turned his army towards Wales. By 26 September he was in Shrewsbury ready to invade Wales. In a lightning campaign, Henry led his army around North Wales. He was harassed constantly by bad weather and the attacks of Welsh guerrillas.[12] When he arrived on Anglesey, he harried the island, burning villages and monasteries including the Llanfaes Friary near Bangor, Gwynedd.[13] This was the historical burial place of the Tudor family.[14] Rhys ap Tudur led an ambush of the king's forces at a place called Rhos Fawr ('the Great Moor').[15] After they were engaged, the Englishmen fled back to the safety of Beaumaris Castle.[13] By 15 October, Henry was back in Shrewsbury, where he released some prisoners, and two days later at Worcester with little to show for his efforts.[12]

In 1401, the revolt began to spread. Much of northern and central Wales went over to Owain. Multiple attacks were recorded on English towns, castles, and manors throughout the north. Even in the south in Brecon and Gwent reports began to come in of banditry and lawlessness. King Henry appointed Henry "Hotspur" Percy – the warrior son of the powerful Earl of Northumberland – to bring the country to order.[12] An amnesty was issued in March which applied to all rebels with the exception of Owain and his cousins, Rhys and Gwilym ap Tudur.[16]

Most of the country agreed to pay all the usual taxes, but the Tudurs knew that they needed a bargaining chip if they were to lift the dire threat hanging over them. They decided to capture Edward I's great castle at Conwy. Although the Conwy Castle garrison amounted to just fifteen men-at-arms and sixty archers, it was well stocked and easily reinforced from the sea; and in any case, the Tudurs only had forty men. On Good Friday, 1 April, all but five of the garrison were in the little church in the town when a carpenter appeared at the castle gate, who, according to Adam of Usk's Chronicon, "feigned to come for his accustomed work". Once inside, the Welsh carpenter attacked the two guards and threw open the gate to allow entry to the rebels.[12] When Percy arrived from Denbigh with 120 men-at-arms and 300 archers, he knew it would take a great deal more to get inside so formidable a fortress and was forced to negotiate.[12] A compromise was reached which would have resulted in pardons issued, but on 20 April, the king overruled Percy's local decision. It was not until Gwilym ap Tudur began to write directly to the king that an agreement was reached on 24 June.[16] However, this was on the condition that nine of the defenders be turned over to justice.[12]

Owain also scored his first major victory in the field in May or June, at Mynydd Hyddgen near Pumlumon. Owain and his army of a few hundred were camped at the bottom of the Hyddgen Valley when about fifteen hundred English and Flemish settlers from Pembrokeshire ('little England beyond Wales'), charged down on them. Owain rallied his much smaller army and fought back, reportedly killing 200.[17] The situation was sufficiently serious for the king to assemble another punitive expedition. This time he attacked in October through central Wales. From Shrewsbury and Hereford Castle, Henry IV's forces drove through Powys toward the Strata Florida Abbey. The Cistercian house was known to be sympathetic towards Owain, and Henry intended to remind them of their loyalties and prevent the revolt from spreading any further south. After much harassment by Owain's forces he reached the abbey. Henry was in no mood to be merciful. His army partially destroyed the abbey and executed a monk suspected of bearing arms against him. However, he failed to engage Owain's forces in any large numbers. Owain's forces harassed him and engaged in hit-and-run tactics on his supply chain, but refused to fight in the open. Henry's army was forced to retreat. They arrived at Worcester on 28 October 1401[18] with little to claim for their efforts. The year came to end with the Battle of Tuthill, an inconclusive battle fought during Owain's siege of Caernarfon Castle on 2 November 1401. The English saw that if the revolt prospered it would inevitably attract disaffected supporters of the deposed King Richard, rumours of whose survival were widely circulating. They were concerned about the potential for disaffection in Cheshire and were increasingly worried about the news from North Wales. Hotspur complained that he was not receiving sufficient support from the king and that the repressive policy of Henry was only encouraging revolt. He argued that negotiation and compromise could persuade Owain to end his revolt. In fact, as early as 1401, Hotspur may have been in secret negotiations with Owain and other leaders of the revolt to try to negotiate a settlement.[19]

Anti-Welsh laws

editDue to the ongoing peace negotiations between Hotspur and Glyndwr proving to be fruitless, the core Lancastrian supporters would have none of this hesitancy, and they struck back with anti-Welsh legislation, the Penal Laws against Wales 1402 which were designed to establish English dominance in Wales.[20][21] The laws included prohibiting any Welshman from buying land in England, from holding any senior public office in Wales, from bearing arms, and from holding any castle or defending any house; no Welsh child was to be educated or apprenticed to any trade, no Englishman could be convicted in any suit brought by a Welshman, Welshmen were to be severely penalised when marrying English women, any Englishman marrying a Welsh woman was disenfranchised, and all public assembly was forbidden.[22] These laws sent a message to any of those who were wavering that the English viewed all the Welsh with equal suspicion. Many Welshmen who had tried to further their careers in English service now felt pushed into the rebellion as the middle ground between Owain and Henry disappeared.

Revolt spreads

editIn the same year, 1402, Owain captured his arch enemy, Reynald or Reginald Grey, 3rd Baron Grey de Ruthyn in an ambush in late January or early February at Ruthin.[23] He held him for a year until he received a substantial ransom from King Henry. In June 1402, Owain's forces encountered an army led by Sir Edmund Mortimer, the uncle of the Earl of March, at Bryn Glas in central Wales. Mortimer's army was badly defeated and Mortimer was captured. It is reported that the Welsh women following Owain's army killed the wounded English soldiers and mutilated the bodies of the dead, supposedly in revenge for plundering and rape by the English soldiery the previous year. Glyndŵr offered to release Mortimer for a large ransom, but Henry IV refused to pay. Mortimer could be said to have had a greater claim to the English throne than himself, so his speedy release was not an option. In response, Sir Edmund negotiated an alliance with Owain and married one of Owain's daughters, Catrin.[24]

In 1403 the revolt became truly national in Wales. Owain struck out to the west and the south. Recreating Llywelyn the Great's campaign in the west, Owain marched down the Tywi Valley. Village after village rose to join him. English manors and castles fell or their inhabitants surrendered. Finally, Carmarthen, one of the main English power-bases in the west, fell and was occupied by Owain. Owain then turned around and attacked Glamorgan and Gwent. Abergavenny Castle was attacked and the walled town burned. Owain pushed on down the valley of the River Usk to the coast, burning Usk and taking Cardiff Castle and Newport Castle. Royal officials reported that Welsh students at the University of Oxford were leaving their studies for Owain and Welsh labourers and craftsmen were abandoning their employers in England and returning to Wales in droves.[25]

In the north of Wales, Owain's supporters launched a further attack on Caernarfon Castle (this time with French support) and almost captured it.[26] In response, Henry of Monmouth (son of Henry IV and the future Henry V) attacked and burned Owain's homes at Glyndyfrdwy and Sycharth. On 10 July 1403, Hotspur declared against the king by challenging his cousin Henry's right to the throne and by raising his standard in revolt in Cheshire at Chester, a bastion of support for King Richard II. Henry of Monmouth, then only 16, turned to the north to meet Hotspur. On 21 July, Henry arrived in Shrewsbury just before Hotspur, forcing the rebel army to camp outside the town. Henry forced the battle before the Earl of Northumberland had also managed to reach Shrewsbury. Thus, on 22 July, Henry was able to fight before the full strength of the rebels was present and on ground of his own choosing. The battle lasted all day, Prince Henry was badly wounded in the face by an arrow but continued to fight alongside his men. When the cry went out that Hotspur had fallen, the rebels' resistance began to falter and crumble. By the end of the day, Hotspur was dead and his rebellion was over. Over 300 knights had died and up to 20,000 men were killed or injured.

In the summer of 1404, Owain captured the great western castles of Harlech and Aberystwyth.[27] Anxious to demonstrate his seriousness as a ruler, he held court at Harlech and appointed the deft and brilliant Gruffydd Young as his chancellor. Soon afterwards he was said by Adam of Usk to have called his first Parliament (or more properly a Cynulliad or "gathering"[a]) of all Wales at Machynlleth where he was crowned Prince of Wales. Senior churchmen and important members of society flowed to his banner. English resistance was reduced to a few isolated castles, walled towns, and fortified manor houses.

Tripartite indenture and the year of the French

editOwain demonstrated his new status by negotiating the "Tripartite Indenture" in February 1405 with Edmund Mortimer and Henry Percy the 1st Earl of Northumberland.[24] The Indenture agreed to divide England and Wales between the three of them. Wales would extend as far as the rivers Severn and Mersey including most of Cheshire, Shropshire, and Herefordshire. The Mortimer Lords of March would take all of southern and western England and Thomas Percy, 1st Earl of Worcester, would take the north of England. Local English communities in Shropshire, Herefordshire and Montgomeryshire had ceased active resistance and were making their own treaties with the rebels. It was rumoured that old allies of Richard II were sending money and arms to the Welsh and the Cistercians and Franciscans were funneling funds to support the rebellion. Furthermore, the Percy rebellion was still viable; even after the defeat of the Percy Archbishop Scrope in May. In fact the Percy rebellion was not to end until 1408 when the Sheriff of Yorkshire defeated Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland at Bramham Moor. Owain was capitalising on the political situation to make the best deal he possibly could.

Things were improving on the international front too. Although negotiations with the Lords of Ireland were unsuccessful, Owain had reasons to hope that the French and Bretons might be more welcoming. In May 1404, Owain had dispatched Gruffydd Young and his brother-in-law, John Hanmer, to France to negotiate a treaty with the French. The result was a formal treaty that promised French aid to Owain and the Welsh. Joint Welsh and Franco-Breton forces had already attacked and laid siege to Kidwelly Castle in November 1403.[26] The Welsh could also count on semi-official aid from Brittany (which was a French vassal at the time) and the then independent Scotland.[24]

Rebellion flounders

editIn 1406, Owain announced his national programme. He declared his vision of an independent Welsh state with a parliament and separate Welsh church. There would be two national universities (one in the south and one in the north) and return to the traditional law of Hywel Dda.[28] By this time, most French forces had withdrawn after politics shifted in Paris toward the peace party. Even Owain's so-called "Pennal Letter", in which he promised Charles VI of France and Avignon Pope Benedict XIII to shift the allegiance of the Welsh Church from Rome to Avignon, produced no effect. The moment had passed.

There were other signs the revolt was encountering problems. Early in the year Owain's forces suffered defeats at Grosmont and Usk at the Battle of Pwll Melyn. Although it is very difficult to understand what happened at these two battles, it appears that Henry of Monmouth or possibly Sir John Talbot defeated substantial Welsh raiding parties led by Rhys Gethin ("Swarthy Rhys") and Owain's eldest son, Gruffudd ab Owain Glyndŵr. The exact date and order of these battles is subject to dispute. However, they may have resulted in the death of Rhys Gethin at Grosmont and Owain's brother, Tudur ap Gruffudd, at Usk and the capture of Gruffudd. Gruffudd was sent to the Tower of London and after six years died in prison. King Henry also showed that the English were engaged in more and more ruthless tactics. Adam of Usk says that after the Battle of Pwll Melyn near Usk, King Henry had three hundred prisoners beheaded in front of Usk Castle. John ap Hywel, Abbot of the nearby Llantarnam Cistercian monastery, was killed during the Battle of Usk as he ministered to the dying and wounded on both sides. More serious for the rebellion, English forces landed in Anglesey from Ireland. Over the next year they would gradually push the Welsh back until the resistance in Anglesey formally ended toward the end of 1406.

At the same time, the English were adopting a different strategy. Rather than focusing on punitive expeditions favoured by his father, the young Henry of Monmouth adopted a strategy of economic blockade. Using the castles that remained in English control he gradually began to retake Wales while cutting off trade and the supply of weapons. By 1407 this strategy was beginning to bear fruit. In March, 1,000 men from all over Flintshire appeared before the Chief Justitiar of the county and agreed to pay a communal fine for their adherence to Glyndŵr. Gradually the same pattern was repeated throughout the country. In July the Earl of Arundel's north-east Lordship around Oswestry and Clun submitted. One by one the Lordships began to surrender. By midsummer, Owain's castle at Aberystwyth was under siege. During the siege, cannons were used by the English in one of the first recorded instances of artillery fire in Britain. That autumn, Aberystwyth Castle surrendered. In 1409 it was the turn of Harlech Castle. Last minute desperate envoys were sent to the French for help. There was no response. Gruffydd Young was sent to Scotland to attempt to coordinate action but nothing was to come of that either. Harlech Castle fell in 1409. Edmund Mortimer died in the final battle and Owain's wife Margaret along with two of his daughters (including Catrin) and three of his Mortimer granddaughters were taken prisoner and incarcerated in the Tower of London. They were all to die in the Tower before 1415.

Owain remained free but now he was a hunted guerilla leader. The revolt continued to splutter on. In 1410, Owain readied his supporters for a last raid deep into Shropshire. Many of his most loyal commanders were present. It may have been a last desperate suicide raid. Whatever was intended, the raid went terribly wrong and many of the leading figures still at large were captured. Rhys Ddu ("Black Rhys") of Cardigan, one of Owain's most faithful commanders, was captured and taken to London for execution. A chronicle of the time states that Rhys Ddu was: "…laid on a hurdle and so drawn forth to Tyburn through the City and was there hanged and let down again. His head was smitten off and his body quartered and sent to four towns and his head set on London Bridge." Philip Scudamore and Rhys ap Tudur were also beheaded and their heads displayed at Shrewsbury and Chester (no doubt to discourage any further thoughts of rebellion).

In 1412, Owain captured, and later ransomed, a leading Welsh supporter of King Henry's, Dafydd Gam ("Crooked David"), in an ambush in Brecon. These were the last flashes of the revolt. This was the last time that Owain was seen alive by his enemies. As late as 1414, there were rumours that the Herefordshire based Lollard leader, Sir John Oldcastle, was communicating with Owain and reinforcements were sent to the major castles in the north and south. Outlaws and bandits left over from the rebellion were still active in Snowdonia.

But by then things were changing. King Henry IV died in 1413 and his son King Henry V began to adopt a more conciliatory attitude to the Welsh. Royal Pardons were offered to the major leaders of the revolt and other opponents of his father's regime. In a symbolic and pious gesture, the body of deposed King Richard II was interred in Westminster Abbey. In 1415 Henry V offered a Pardon to Owain, as he prepared for war with France. There is evidence that the new King Henry V was in negotiations with Owain's son, Maredudd ab Owain Glyndŵr, but nothing was to come of it. In 1416 Maredudd was himself offered a Pardon but refused. Perhaps his father Owain was still alive and he was unwilling to accept it while he lived. He finally accepted a Royal Pardon on 8 April 1421, suggesting that Owain Glyndŵr was finally dead.[29] There is some evidence to suggest, in the poetry of the Welsh Bard Llawdden for example, that a few diehards continued to fight on even after 1421 under the leadership of Owain's son-in-law Phylib ap Rhys.

The Annals of Owain Glyndwr (Panton MS. 22) finish in the year 1422. The last entry regarding the prince reads:

- 1415 – Owain went into hiding on St Matthew's Day in Harvest (21 September), and thereafter his hiding place was unknown. Very many said that he died; the seers maintain he did not.[30]

The date of his death remains uncertain but the tentative consensus is that he may have died in 1415.[31]

Aftermath of rebellion in Wales

editBy 1415, full English rule was returned to Wales. The leading rebels were dead, imprisoned, or impoverished through massive fines. Scarcely a parish or family in Wales, English or Welsh, had not been affected in some way. The cost in loss of life, loss of livelihood, and physical destruction was enormous. Wales, already a poor country on the border of England, was further impoverished by pillage, economic blockade and communal fines. Reports by travellers speak of ruined castles, such as Montgomery Castle and Abbeys such as Strata Florida Abbey and Abbeycwmhir. Grass grew in the market squares of many towns such as Oswestry and Welsh commerce had almost ground to a halt. Land that had previously been productive was now empty wasteland with no tenants to work the land. As late as 1492, a Royal Official in lowland Glamorgan was still citing the devastation caused by the revolt as the reason he was unable to deliver promised revenues to the King.[citation needed]

Many prominent families were ruined. In 1411, John Hanmer pleaded poverty as the reason he could not pay the fines imposed on him. The Tudors no longer lorded it over Anglesey and northwest Wales as they had done throughout the late 14th century. The family seemed finished until the third Tudor brother, Maredudd, went to London and established a new destiny for them. Others eventually surrendered and made peace with the new order. Henry Dwn who, with the French and Bretons, had laid siege to Kidwelly Castle in 1403 and 1404 made his peace and accepted a fine. Somehow he avoided paying a penny. For many years after his surrender and despite official proscriptions, he sheltered rebels on the run, levied fines on 200 individuals that had not supported him, rode around the county with his retinue, and even plotted the murder of the King's justice.[citation needed] Nevertheless, his grandson fought alongside Henry V in 1415 at the Battle of Agincourt. Others could not fit into the new order. An unknown number of Owain's supporters went into exile. Henry Gwyn ("White Henry") — heir to the substantial Lordship of Llansteffan — left Wales forever and was to die in the service of Charles VI of France facing his old comrades at the Battle of Agincourt. Gruffydd Young was another permanent exile. By 1415 he was in Paris. He was to live another 20 years being first Bishop of Ross in Scotland and later titular bishop of Hippo in North Africa.[citation needed]

A series of penal laws were put in place, intended to prevent any further uprisings. These remained until the reign of Henry VII of England;[32] also known as Henry Tudor, he was descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and was part-Welsh.[33] Until then, the Welsh were prevented from holding property or land within the Welsh boroughs, were forbidden from serving on juries, could not intermarry with the English and were prevented from holding any office of the crown. Furthermore, in legal practice, a statement by a Welshman could not be used as evidence to implicate an Englishman in court.[32] However, there were several occasions where Welshmen were granted the legal status of Englishmen, such as Edmund and Jasper Tudor, the half brothers of Henry VI of England. However, the Tudor brothers' father, Owen Tudor was arrested as he had married the Queen dowager, Catherine of Valois, in secret.[34][35] Henry VI saw to his release and inclusion in the Royal Household.[36]

The revolt was the last major manifestation of a Welsh independence movement before the annexation of Wales into England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542.[37] The Acts were passed during the reign of King Henry VIII of England, of the Tudor dynasty, and came into effect in 1543.[38]

Notes

edit- ^ Cynulliad is also the word used in the Welsh language for the 1999-established National Assembly for Wales.

References

edit- ^ Williams 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Barber 2004, p. 21.

- ^ a b BBC.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Tout 1900, p. 9.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 75.

- ^ Tout 1900, p. 10.

- ^ Davies 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Davies 1997, p. 266.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f Bradley 1901.

- ^ a b Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 21.

- ^ Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 17.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 84.

- ^ a b Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 22.

- ^ Grant 2011, p. 212.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Davies 2009.

- ^ Jones & Smith 1999.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 360.

- ^ Parry 2010, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Pierce 1959.

- ^ Ellis 1832.

- ^ a b Parry 2010, p. 183.

- ^ Gravett & Hook 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Williams 1993, p. 4.

- ^ Davies 1997, p. 293.

- ^ Lloyd 1931, p. 154.

- ^ Williams 1993, p. 5.

- ^ a b Evans 1915, p. 19.

- ^ Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 5.

- ^ Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 29.

- ^ Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 32.

- ^ Griffiths & Thomas 1985, p. 33.

- ^ Davies 1997, p. 324.

- ^ Williams 1985, p. 122.

Bibliography

edit- Barber, Chris (2004). In search of Owain Glyndŵr. Abergavenny, Monmouthshire : Blorenge Books. ISBN 978-1-872730-33-2. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "BBC Wales – History – Themes – Chapter 10: The revolt of Owain Glyndwr". Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- Bradley, A.G. (1901). Owen Glyndwr and the Last Struggle for Welsh Independence. New York: Putnam.

- Brough, Gideon (2017). The Rise and Fall of Owain Glyn Dŵr. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781786721105.

- Davies, R. R. (1997). The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285336-3.

- Davies, R. R. (2009). Owain Glyndwr - Prince of Wales. Y Lolfa. ISBN 978-1-84771-763-4.

- Ellis, Henry (1832). "III. Letter from Henry Ellis, Esq. F.R.S. Secretary, addressed to the Right Honourable the Earl of Aberdeen, K. T. President, accompanying Transcripts of three Letters illustrative of English History". Archaeologia. 24: 137–147. doi:10.1017/s0261340900018646. ISSN 0261-3409.

- Evans, Howell T. (1915). Wales and the Wars of the Roses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grant, R.G., ed. (2011). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of History. New York. p. 212. ISBN 9780785835530. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Gravett, Christopher; Hook, Adam (2007). The castles of Edward I in Wales, 1277-1307. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 9781846030277.

- Griffiths, Ralph Alan; Thomas, Roger S. (1985). The Making of the Tudor Dynasty. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-31250-745-9.

- Hodges, Geoffrey (1995). Owain Glyn Dŵr and the War of Independence in the Welsh Borders. Little Logaston, Woonton Almeley, Herefordshire [England]: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-873827-24-6.

- Jones, Gareth Elwyn; Smith, Dai (1999). The People of Wales. Gomer. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-85902-743-1.

- Latimer, Jon (2001). Deception in War. London: J. Murray. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-7195-5605-0.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1931). Owen Glendower. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Parry, Charles (2010). The Last Mab Darogan: The Life and Times of Owain Glyn Dŵr. Novasys Limited. ISBN 978-0-9565553-0-4.

- Pierce, Thomas Jones (1959). "OWAIN GLYNDWR (c. 1354 - 1416), 'Prince of Wales'". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- Tout, Thomas Frederick (1900). Owain Glyndwr and his Times. Dartford: Perry and Son.

- Williams, Glanmor (1993). Renewal and Reformation: Wales c.1415-1642. Oxford: Clarendon. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780192852779.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-167055-8.

- Williams, Glanmor (2005). Owain Glyndŵr. Cardiff : University of Wales. ISBN 978-0-7083-1941-3. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- Williams, Gwyn A. (1985). When was Wales? : a history of the Welsh. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140225891.