German Americans (German: Deutschamerikaner, pronounced [ˈdɔʏtʃʔameʁɪˌkaːnɐ]) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry.

Deutschamerikaner (German) | |

|---|---|

Hybrid flag of the US and Germany | |

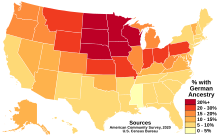

Americans with German Ancestry by state according to the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey in 2020 | |

| Total population | |

| Alone (one ancestry) 15,447,670 (2020 census)[1] 4.66% of the total US population Alone or in combination 44,978,546 (2020 census)[1] 13.57% of the total US population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nationwide, most notably in the Midwest, though less common in New England, California, New Mexico, and the Deep South.[2] Plurality in Pennsylvania,[3] Upstate New York,[4] Colorado, the Southwest,[5] and the Pacific Northwest. | |

| Languages | |

| American English, German | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

According to the United States Census Bureau's figures from 2022, German Americans make up roughly 41 million people in the US, which is approximately 12% of the population.[7] This represents a decrease from the 2012 census where 50.7 million Americans identified as German.[8] The census is conducted in a way that allows this total number to be broken down in two categories. In the 2020 census, roughly two thirds of those who identify as German also identified as having another ancestry, while one third identified as German alone.[9] German Americans account for about one third of the total population of people of German ancestry in the world.[10][11]

The first significant groups of German immigrants arrived in the British colonies in the 1670s, and they settled primarily in the colonial states of Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia.

The Mississippi Company of France later transported thousands of Germans from Europe to what was then the German Coast, Orleans Territory in present-day Louisiana between 1718 and 1750.[12] Immigration to the U.S. ramped up sharply during the 19th century.

There is a German belt consisting of areas with predominantly German American populations that extends across the United States from eastern Pennsylvania, where many of the first German Americans settled, to the Oregon coast.

Pennsylvania, with 3.5 million people of German ancestry, has the largest population of German-Americans in the U.S. and is home to one of the group's original settlements, the Germantown section of present-day Philadelphia, founded in 1683. Germantown is also the birthplace of the American antislavery movement, which emerged there in 1688.

Germantown also was the location of the Battle of Germantown, an American Revolutionary War battle fought between the British Army, led by William Howe, and the Continental Army, led by George Washington, on October 4, 1777.

German Americans were drawn to colonial-era British America by its abundant land and religious freedom, and were pushed out of Germany by shortages of land and religious or political oppression.[13] Many arrived seeking religious or political freedom, others for economic opportunities greater than those in Europe, and others for the chance to start fresh in the New World. The arrivals before 1850 were mostly farmers who sought out the most productive land, where their intensive farming techniques would pay off. After 1840, many came to cities, where German-speaking districts emerged.[14][15][16]

German Americans established the first kindergartens in the United States,[17] introduced the Christmas tree tradition,[18][19] and introduced popular foods such as hot dogs and hamburgers to America.[20]

The great majority of people with some German ancestry have become Americanized; fewer than five percent speak German. German-American societies abound, as do celebrations that are held throughout the country to celebrate German heritage of which the German-American Steuben Parade in New York City is one of the most well-known and is held every third Saturday in September. Oktoberfest celebrations and the German-American Day are popular festivities. There are major annual events in cities with German heritage including Chicago, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, San Antonio, and St. Louis.

Around 190,000 permanent residents from Germany were living in the United States in 2025.[21]

History

editThe Germans included many quite distinct subgroups with differing religious and cultural values.[23] Lutherans and Catholics typically opposed Yankee moralizing programs such as the prohibition of beer, and favored paternalistic families with the husband deciding the family position on public affairs.[24][25] They generally opposed women's suffrage but this was used as argument in favor of suffrage when German Americans became pariahs during World War I.[26] On the other hand, there were Protestant groups who emerged from European pietism such as the German Methodist and United Brethren; they more closely resembled the Yankee Methodists in their moralism.[27]

Colonial era

editThe first English settlers arrived at Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, and were accompanied by the first German that was to settle in North America, physician and botanist Johannes (John) Fleischer (in South America Ambrosius Ehinger had already founded Maracaibo in 1529). He was followed in 1608 by five glassmakers and three carpenters or house builders.[28] The first permanent German settlement in what became the United States was Germantown, Pennsylvania, founded near Philadelphia on October 6, 1683.[29]

Large numbers of Germans migrated from the 1680s to 1760s, with Pennsylvania the favored destination. They migrated to America for a variety of reasons.[29] Push factors involved worsening opportunities for farm ownership in central Europe, persecution of some religious groups, and military conscription; pull factors were better economic conditions, especially the opportunity to own land, and religious freedom. Often immigrants paid for their passage by selling their labor for a period of years as indentured servants.[30]

Large sections of Pennsylvania, Upstate New York, and the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia attracted Germans. Most were Lutheran or German Reformed; many belonged to small religious sects such as the Moravians and Mennonites. German Catholics did not arrive in number until after the War of 1812.[31]

Palatines

editIn 1709, Protestant Germans from the Pfalz or Palatine region of Germany escaped conditions of poverty, traveling first to Rotterdam and then to London. Queen Anne helped them get to the American colonies. The trip was long and difficult to survive because of the poor quality of food and water aboard ships and the infectious disease typhus. Many immigrants, particularly children, died before reaching America in June 1710.[32]

The Palatine immigration of about 2100 people who survived was the largest single immigration to America in the colonial period. Most were first settled along the Hudson River in work camps, to pay off their passage. By 1711, seven villages had been established in New York on the Robert Livingston manor. In 1723 Germans became the first Europeans allowed to buy land in the Mohawk Valley west of Little Falls. One hundred homesteads were allocated in the Burnetsfield Patent. By 1750, the Germans occupied a strip some 12 miles (19 km) long along both sides of the Mohawk River. The soil was excellent; some 500 houses were built, mostly of stone, and the region prospered in spite of Indian raids. Herkimer was the best-known of the German settlements in a region long known as the "German Flats".[32]

They kept to themselves, married their own, spoke German, attended Lutheran churches, and retained their own customs and foods. They emphasized farm ownership. Some mastered English to become conversant with local legal and business opportunities. They tolerated slavery (although few were rich enough to own a slave).[33]

The most famous of the early German Palatine immigrants was editor John Peter Zenger, who led the fight in colonial New York City for freedom of the press in America. A later immigrant, John Jacob Astor, who came from Walldorf, Electoral Palatinate, since 1803 Baden, after the Revolutionary War, became the richest man in America from his fur trading empire and real estate investments in New York.[34]

Louisiana

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

John Law organized the first colonization of Louisiana with German immigrants. Of the over 5,000 Germans initially immigrating primarily from the Alsace Region as few as 500 made up the first wave of immigrants to leave France en route to the Americas. Less than 150 of those first indentured German farmers made it to Louisiana and settled along what became known as the German Coast. With tenacity, determination and the leadership of D'arensburg these Germans felled trees, cleared land, and cultivated the soil with simple hand tools as draft animals were not available. The German coast settlers supplied the budding City of New Orleans with corn, rice, eggs. and meat for many years following.

The Mississippi Company settled thousands of German pioneers in French Louisiana during 1721. It encouraged Germans, particularly Germans of the Alsatian region who had recently fallen under French rule, and the Swiss to immigrate. Alsace was sold to France within the greater context of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).

The Jesuit Charlevoix traveled New France (Canada and Louisiana) in the early 1700s. His letter said "these 9,000 Germans, who were raised in the Palatinate (Alsace part of France) were in Arkansas. The Germans left Arkansas en masse. They went to New Orleans and demanded passage to Europe. The Mississippi Company gave the Germans rich lands on the right bank of the Mississippi River about 25 miles (40 km) above New Orleans. The area is now known as 'the German Coast'."

A thriving population of Germans lived upriver from New Orleans, Louisiana, known as the German Coast. They were attracted to the area through pamphlets such as J. Hanno Deiler's "Louisiana: A Home for German Settlers".[35]

Southeast

editTwo waves of German colonists in 1714 and 1717 founded a colony in Virginia called Germanna,[36] located near modern-day Culpeper, Virginia. Virginia Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood, taking advantage of the headright system, had bought land in present-day Spotsylvania and encouraged German immigration by advertising in Germany for miners to move to Virginia and establish a mining industry in the colony. The name "Germanna", selected by Governor Alexander Spotswood, reflected both the German immigrants who sailed across the Atlantic to Virginia and the British queen, Anne, who was in power at the time of the first settlement at Germanna. In 1721, twelve German families departed Germanna to found Germantown. They were swiftly replaced by 70 new German arrivals from the Palatinate, the start of a westward and southward trend of German migration and settlement across the Virginia Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley around the Blue Ridge Mountains, where Palatine German predominated. Meanwhile, in Southwest Virginia, Virginia German acquired a Swabian German accent.[37][38][39]

In North Carolina, an expedition of German Moravians living around Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and a party from Europe led by August Gottlieb Spangenberg, headed down the Great Wagon Road and purchased 98,985 acres (400.58 km2) from Lord Granville (one of the British Lords Proprietor) in the Piedmont of North Carolina in 1753. The tract was dubbed Wachau-die-Aue, Latinized Wachovia, because the streams and meadows reminded Moravian settlers of the Wachau valley in Austria.[40][41][42] They established German settlements on that tract, especially in the area around what is now Winston-Salem.[43][44] They also founded the transitional settlement of Bethabara, North Carolina, translated as House of Passage, the first planned Moravian community in North Carolina, in 1759. Soon after, the German Moravians founded the town of Salem in 1766 (now a historical section in the center of Winston-Salem) and Salem College (an early female college) in 1772.

In the Georgia Colony, Germans mainly from the Swabia region settled in Savannah, St. Simon's Island and Fort Frederica in the 1730s and 1740s. They were actively recruited by James Oglethorpe and quickly distinguished themselves through improved farming, advanced tabby (cement)-construction, and leading joint Lutheran-Anglican-Reformed religious services for the colonists.

German immigrants also settled in other areas of the American South, including around the Dutch (Deutsch) Fork area of South Carolina,[31] and Texas, especially in the Austin and San Antonio areas.

New England

editBetween 1742 and 1753, roughly 1,000 Germans settled in Broad Bay, Massachusetts (now Waldoboro, Maine). Many of the colonists fled to Boston, Maine, Nova Scotia, and North Carolina after their houses were burned and their neighbors killed or carried into captivity by Native Americans. The Germans who remained found it difficult to survive on farming, and eventually turned to the shipping and fishing industries.[45]

Pennsylvania

editThe tide of German immigration to Pennsylvania swelled between 1725 and 1775, with immigrants arriving as redemptioners or indentured servants. By 1775, Germans constituted about one-third of the population of the state. German farmers were renowned for their highly productive animal husbandry and agricultural practices. Politically, they were generally inactive until 1740, when they joined a Quaker-led coalition that took control of the legislature, which later supported the American Revolution. Despite this, many of the German settlers were loyalists during the Revolution, possibly because they feared their royal land grants would be taken away by a new republican government, or because of loyalty to a British German monarchy who had provided the opportunity to live in a liberal society.[46] The Germans, comprising Lutherans, Reformed, Mennonites, Amish, and other sects, developed a rich religious life with a strong musical culture. Collectively, they came to be known as the Pennsylvania Dutch (from Deutsch).[47][48]

Etymologically, the word Dutch originates from the Old High German word "diutisc" (from "diot" "people"), referring to the Germanic "language of the people" as opposed to Latin, the language of the learned (see also theodiscus). Eventually the word came to refer to people who speak a Germanic language, and only in the last couple centuries the people of the Netherlands. Other Germanic language variants for "deutsch/deitsch/dutch" are: Dutch "Duits" and "Diets", Yiddish "daytsh", Danish/Norwegian "tysk", or Swedish "tyska." The Japanese "ドイツ" (/doitsu/) also derives from the aforementioned "Dutch" variations.

The Studebaker brothers, forefathers of the wagon and automobile makers, arrived in Pennsylvania in 1736 from the famous blade town of Solingen. With their skills, they made wagons that carried the frontiersmen westward; their cannons provided the Union Army with artillery in the American Civil War, and their automobile company became one of the largest in America, although never eclipsing the "Big Three", and was a factor in the war effort and in the industrial foundations of the Army.[49]

American Revolution

editGreat Britain, whose King George III was also the Elector of Hanover in Germany, hired 18,000 Hessians. They were mercenary soldiers rented out by the rulers of several small German states such as Hesse to fight on the British side. Many were captured; they remained as prisoners during the war but some stayed and became U.S. citizens.[51] In the American Revolution the Mennonites and other small religious sects were neutral pacifists. The Lutherans of Pennsylvania were on the patriot side.[52] The Muhlenberg family, led by Rev. Henry Muhlenberg was especially influential on the Patriot side.[53] His son Peter Muhlenberg, a Lutheran clergyman in Virginia became a major general and later a Congressman.[54][55] However, in upstate New York, many Germans were neutral or supported the Loyalist cause.

From names in the 1790 U.S. census, historians estimate Germans constituted nearly 9% of the white population in the United States.[56]

Colonial German American population by state

edit| State or Territory | Germans | |

|---|---|---|

| # | % | |

| Connecticut | 697 | 0.30% |

| Delaware | 509 | 1.10% |

| Georgia | 4,019 | 7.60% |

| Kentucky & Tenn. | 13,026 | 14.00% |

| Maine | 1,249 | 1.30% |

| Maryland | 24,412 | 11.70% |

| Massachusetts | 1,120 | 0.30% |

| New Hampshire | 564 | 0.40% |

| New Jersey | 15,636 | 9.20% |

| New York | 25,778 | 8.20% |

| North Carolina | 13,592 | 4.70% |

| Pennsylvania | 140,983 | 33.30% |

| Rhode Island | 323 | 0.50% |

| South Carolina | 7,009 | 5.00% |

| Vermont | 170 | 0.20% |

| Virginia | 27,853 | 6.30% |

| 1790 Census Area | 276,940 | 8.73% |

| Northwest Territory | 445 | 4.24% |

| French America | 1,750 | 8.75% |

| Spanish America | 85 | 0.35% |

| United States | 279,220 | 8.65% |

The brief Fries's Rebellion was an anti-tax movement among Germans in Pennsylvania in 1799–1800.[58]

19th century

edit| German Immigration to United States (1820–2004)[59] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigration period |

Number of immigrants |

Immigration period |

Number of immigrants |

| 1820–1840 | 160,335 | 1921–1930 | 412,202 |

| 1841–1850 | 434,626 | 1931–1940 | 114,058 |

| 1851–1860 | 951,667 | 1941–1950 | 226,578 |

| 1861–1870 | 787,468 | 1951–1960 | 477,765 |

| 1871–1880 | 718,182 | 1961–1970 | 190,796 |

| 1881–1890 | 1,452,970 | 1971–1980 | 74,414 |

| 1891–1900 | 505,152 | 1981–1990 | 91,961 |

| 1901–1910 | 341,498 | 1991–2000 | 92,606 |

| 1911–1920 | 143,945 | 2001–2004 | 61,253 |

| Total: 7,237,594 | |||

The largest flow of German immigration to America occurred between 1820 and World War I, during which time nearly six million Germans immigrated to the United States. From 1840 to 1880, they were the largest group of immigrants. Following the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, a wave of political refugees fled to America, who became known as Forty-Eighters. They included professionals, journalists, and politicians. Prominent Forty-Eighters included Carl Schurz and Henry Villard.[60]

"Latin farmer" or Latin Settlement is the designation of several settlements founded by some of the Dreissiger and other refugees from Europe after rebellions like the Frankfurter Wachensturm beginning in the 1830s—predominantly in Texas and Missouri, but also in other U.S. states—in which German intellectuals (freethinkers, German: Freidenker, and Latinists) met together to devote themselves to the German literature, philosophy, science, classical music, and the Latin language. A prominent representative of this generation of immigrants was Gustav Koerner who lived most of the time in Belleville, Illinois until his death.

Jewish Germans

editA few German Jews came in the colonial era. The largest numbers arrived after 1820, especially in the mid-19th century.[61] They spread across the North and South (and California, where Levi Strauss arrived in 1853). They formed small German-Jewish communities in cities and towns. They typically were local and regional merchants selling clothing; others were livestock dealers, agricultural commodity traders, bankers, and operators of local businesses. Henry Lehman, who founded Lehman Brothers in Alabama, was a particularly prominent example of such a German-Jewish immigrant. They formed Reform synagogues[62] and sponsored numerous local and national philanthropic organizations, such as B'nai B'rith.[63] This German-speaking group is quite distinct from the Yiddish-speaking East-European Jews who arrived in much larger numbers starting in the late 19th century and concentrated in New York.

Northeastern cities

editThe port cities of New York City, and Baltimore had large populations, as did Hoboken, New Jersey.

Cities of the Midwest

editIn the 19th century, German immigrants settled in Midwest, where land was available. Cities along the Great Lakes, the Ohio River, and the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers attracted a large German element. The Midwestern cities of Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago were favored destinations of German immigrants. The Northern Kentucky and Louisville area along the Ohio River was also a favored destination. By 1900, the populations of the cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati were all more than 40% German American. Dubuque and Davenport, Iowa had even larger proportions, as did Omaha, Nebraska, where the proportion of German Americans was 57% in 1910. In many other cities of the Midwest, such as Fort Wayne, Indiana, German Americans were at least 30% of the population.[45][64] By 1850 there were 5,000 Germans, mostly Schwabians living in, and around, Ann Arbor, Michigan.[65]

Many concentrations acquired distinctive names suggesting their heritage, such as the "Over-the-Rhine" district in Cincinnati, "Dutchtown" in South St Louis, and "German Village" in Columbus, Ohio.[66]

A particularly attractive destination was Milwaukee, which came to be known as "the German Athens". Radical Germans trained in politics in the old country dominated the city's Socialists. Skilled workers dominated many crafts, while entrepreneurs created the brewing industry; the most famous brands included Pabst, Schlitz, Miller, and Blatz.[67]

Whereas half of German immigrants settled in cities, the other half established farms in the Midwest. From Ohio to the Plains states, a heavy presence persists in rural areas into the 21st century.[31][68]

Deep South

editFew German immigrants settled in the Deep South, apart from New Orleans, the German Coast, and Texas.[69]

Texas

editTexas attracted many Germans who entered through Galveston and Indianola, both those who came to farm, and later immigrants who more rapidly took industrial jobs in cities such as Houston. As in Milwaukee, Germans in Houston built the brewing industry. By the 1920s, the first generation of college-educated German Americans were moving into the chemical and oil industries.[31]

Texas had about 20,000 German Americans in the 1850s. They did not form a uniform bloc, but were highly diverse and drew from geographic areas and all sectors of European society, except that very few aristocrats or upper middle class businessmen arrived. In this regard, Texas Germania was a microcosm of the Germania nationwide.

The Germans who settled Texas were diverse in many ways. They included peasant farmers and intellectuals; Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and atheists; Prussians, Saxons, and Hessians; abolitionists and slave owners; farmers and townsfolk; frugal, honest folk and ax murderers. They differed in dialect, customs, and physical features. A majority had been farmers in Germany, and most arrived seeking economic opportunities. A few dissident intellectuals fleeing the 1848 revolutions sought political freedom, but few, save perhaps the Wends, went for religious freedom. The German settlements in Texas reflected their diversity. Even in the confined area of the Hill Country, each valley offered a different kind of German. The Llano valley had stern, teetotaling German Methodists, who renounced dancing and fraternal organizations; the Pedernales valley had fun-loving, hardworking Lutherans and Catholics who enjoyed drinking and dancing; and the Guadalupe valley had freethinking Germans descended from intellectual political refugees. The scattered German ethnic islands were also diverse. These small enclaves included Lindsay in Cooke County, largely Westphalian Catholic; Waka in Ochiltree County, Midwestern Mennonite; Hurnville in Clay County, Russian German Baptist; and Lockett in Wilbarger County, Wendish Lutheran.[71]

Germans from Russia

editGermans from Russia were the most traditional of German-speaking arrivals. They were Germans who had lived for generations throughout the Russian Empire, but especially along the Volga River and the Black Sea. Their ancestors had come from all over the German-speaking world, invited by Catherine the Great in 1762 and 1763 to settle and introduce more advanced German agriculture methods to rural Russia. They had been promised by the manifesto of their settlement the ability to practice their respective Christian denominations, retain their culture and language, and retain immunity from conscription for them and their descendants. As time passed, the Russian monarchy gradually eroded the ethnic German population's relative autonomy. Conscription eventually was reinstated; this was especially harmful to the Mennonites, who practice pacifism. Throughout the 19th century, pressure increased from the Russian government to culturally assimilate. Many Germans from Russia found it necessary to emigrate to avoid conscription and preserve their culture. About 100,000 immigrated by 1900, settling primarily in the Great Plains.

Negatively influenced by the violation of their rights and cultural persecution by the Tsar, the Germans from Russia who settled in the northern Midwest saw themselves as a downtrodden ethnic group separate from Russian Americans and having an entirely different experience from the German Americans who had emigrated from German lands. They settled in tight-knit communities who retained their German language and culture. They raised large families, built German-style churches, buried their dead in distinctive cemeteries using cast iron grave markers, and sang German hymns. Many farmers specialized in the production of sugar beets and wheat, which are still major crops in the upper Great Plains. During World War I, their identity was challenged by anti-German sentiment. By the end of World War II, the German language, which had always been used with English for public and official matters, was in serious decline. Today, German is preserved mainly through singing groups, recipes, and educational settings. While most descendants of Germans from Russia primarily speak English, many are choosing to learn German in an attempt to reconnect with their heritage. Germans from Russia often use loanwords, such as Kuchen for cake. Despite the loss of their language, the ethnic group remains distinct, and has left a lasting impression on the American West.[72]

Musician Lawrence Welk (1903–1992) became an iconic figure in the German-Russian community of the northern Great Plains—his success story personified the American dream.[73]

Civil War

editSentiment among German Americans was largely anti-slavery, especially among Forty-Eighters.[74] Notable Forty-Eighter Hermann Raster wrote passionately against slavery and was very pro-Lincoln. Raster published anti-slavery pamphlets and was the editor of the most influential German language newspaper in America at the time.[75] He helped secure the votes of German-Americans across the United States for Abraham Lincoln. When Raster died the Chicago Tribune published an article regarding his service as a correspondent for America to the German states saying, "His writings during and after the Civil War did more to create understanding and appreciation of the American situation in Germany and to float U.S. bonds in Europe than the combined efforts of all the U.S. ministers and consuls."[76] Hundreds of thousands of German Americans volunteered to fight for the Union in the American Civil War (1861–1865).[77] The Germans were the largest immigrant group to participate in the Civil War; over 176,000 U.S. soldiers were born in Germany.[78] A popular Union commander among Germans, Major General Franz Sigel was the highest-ranking German officer in the Union Army, with many German immigrants claiming to enlist to "fight mit Sigel".[79]

Although only one in four Germans fought in all-German regiments, they created the public image of the German soldier. Pennsylvania fielded five German regiments, New York eleven, and Ohio six.[77]

Farmers

editWestern railroads, with large land grants available to attract farmers, set up agencies in Hamburg and other German cities, promising cheap transportation, and sales of farmland on easy terms. For example, the Santa Fe railroad hired its own commissioner for immigration, and sold over 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) to German-speaking farmers.[80]

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the German Americans showed a high interest in becoming farmers, and keeping their children and grandchildren on the land. While they needed profits to stay in operation, they used profits as a tool "to maintain continuity of the family".[81] They used risk averse strategies, and carefully planned their inheritances to keep the land in the family. Their communities showed smaller average farm size, greater equality, less absentee ownership and greater geographic persistence. As one farmer explained, "To protect your family has turned out to be the same thing as protecting your land."[82]

Germany was a large country with many diverse subregions which contributed immigrants. Dubuque was the base of the Ostfriesische Nachrichten ("East Frisian News") from 1881 to 1971. It connected the 20,000 immigrants from East Friesland (Ostfriesland), Germany, to each other across the Midwest, and to their old homeland. In Germany East Friesland was often a topic of ridicule regarding backward rustics, but editor Leupke Hündling shrewdly combined stories of proud memories of Ostfriesland. The editor enlisted a network of local correspondents. By mixing local American and local German news, letters, poetry, fiction, and dialogue, the German-language newspaper allowed immigrants to honor their origins and celebrate their new life as highly prosperous farmers with much larger farms than were possible back in impoverished Ostfriesland. During the world wars, when Germania came under heavy attack, the paper stressed its humanitarian role, mobilizing readers to help the people of East Friesland with relief funds. Younger generations could usually speak German but not read it, so the subscription base dwindled away as the target audience Americanized itself.[83]

Politics

editRelatively few German Americans held office, but the men voted once they became citizens. In general during the Third party System (1850s–1890s), the Protestants and Jews leaned toward the Republican party and the Catholics were strongly Democratic. When prohibition was on the ballot, the Germans voted solidly against it. They strongly distrusted moralistic crusaders, whom they called "Puritans", including the temperance reformers and many Populists. The German community strongly opposed Free Silver, and voted heavily against crusader William Jennings Bryan in 1896. In 1900, many German Democrats returned to their party and voted for Bryan, perhaps because of President William McKinley's foreign policy.[84]

At the local level, historians have explored the changing voting behavior of the German-American community and one of its major strongholds, St. Louis, Missouri. The German Americans had voted 80 percent for Lincoln in 1860, and strongly supported the war effort. They were a bastion of the Republican Party in St. Louis and nearby immigrant strongholds in Missouri and southern Illinois. The German Americans were angered by a proposed Missouri state constitution that discriminated against Catholics and freethinkers. The requirement of a special loyalty oath for priests and ministers was troublesome. Despite their strong opposition the constitution was ratified in 1865. Racial tensions with the blacks began to emerge, especially in terms of competition for unskilled labor jobs. Germania was nervous about black suffrage in 1868, fearing that blacks would support puritanical laws, especially regarding the prohibition of beer gardens on Sundays. The tensions split off a large German element in 1872, led by Carl Schurz. They supported the Liberal Republican party led by Benjamin Gratz Brown for governor in 1870 and Horace Greeley for president in 1872.[85]

Many Germans in late 19th century cities were communists; Germans played a significant role in the labor union movement.[86][87] A few were anarchists.[88] Eight of the forty-two anarchist defendants in the Haymarket Affair of 1886 in Chicago were German.

World Wars

editIntellectuals

editHugo Münsterberg (1863–1916), a German psychologist, moved to Harvard in the 1890s and became a leader in the new profession. He was president of the American Psychological Association in 1898, and the American Philosophical Association in 1908, and played a major role in many other American and international organizations.[89]

Arthur Preuss (1871–1934) was a leading journalist, and theologian. A layman in St Louis. His Fortnightly Review (in English) was a major conservative voice read closely by church leaders and intellectuals from 1894 until 1934. He was intensely loyal to the Vatican. Preuss upheld the German Catholic community, denounced the "Americanism" heresy, promoted the Catholic University of America, and anguished over the anti-German America hysteria during World War I. He provided lengthy commentary regarding the National Catholic Welfare Conference, the anti-Catholic factor in the presidential campaign of 1928, the hardships of the Great Depression, and the liberalism of the New Deal.[90][91]

World War I anti-German sentiment

editDuring World War I, German Americans were often accused of being too sympathetic to Imperial Germany. Former president Theodore Roosevelt denounced "hyphenated Americanism", insisting that dual loyalties were impossible in wartime. A small minority came out for Germany, such as H. L. Mencken. Similarly, Harvard psychology professor Hugo Münsterberg dropped his efforts to mediate between America and Germany, and threw his efforts behind the German cause.[92][93] There was also some Anti-German hysteria like the killing of Pastor Edmund Kayser.

The Justice Department prepared a list of all German aliens, counting approximately 480,000 of them, more than 4,000 of whom were imprisoned in 1917–18. The allegations included spying for Germany or endorsing the German war effort.[94] Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty.[95] The Red Cross barred individuals with German last names from joining in fear of sabotage. One person was killed by a mob; in Collinsville, Illinois, German-born Robert Prager was dragged from jail as a suspected spy and lynched.[96] A Minnesota minister was tarred and feathered when he was overheard praying in German with a dying woman.[97] Questions of German American loyalty increased due to events like the German bombing of Black Tom island[98] and the U.S. entering World War I, many German Americans were arrested for refusing allegiance to the U.S.[99] War hysteria led to the removal of German names in public, names of things such as streets,[100] and businesses.[101] Schools also began to eliminate or discourage the teaching of the German language.[102]

In Chicago, Frederick Stock temporarily stepped down as conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra until he finalized his naturalization papers. Orchestras replaced music by German composer Wagner with French composer Berlioz. In Cincinnati, the public library was asked to withdraw all German books from its shelves.[103] German-named streets were renamed. The town, Berlin, Michigan, was changed to Marne, Michigan (honoring those who fought in the Battle of Marne). In Iowa, in the 1918 Babel Proclamation, the governor prohibited all foreign languages in schools and public places. Nebraska banned instruction in any language except English, but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the ban illegal in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska).[104] The response of German Americans to these tactics was often to "Americanize" names (e.g., Schmidt to Smith, Müller to Miller) and limit the use of the German language in public places, especially churches.[105]

-

American wartime propaganda depicted the bloodthirsty German "Hun" soldier as an enemy of civilization, with his eyes on America from across the Atlantic.

-

German American farmer John Meints of Minnesota was tarred and feathered in August 1918 for allegedly not supporting war bond drives.

World War II

editBetween 1931 and 1940, 114,000 Germans moved to the United States, many of whom—including Nobel prize winner Albert Einstein and author Erich Maria Remarque—were Jewish Germans or anti-Nazis fleeing government oppression.[106] About 25,000 people became paying members of the pro-Nazi German American Bund during the years before the war.[107] German aliens were the subject of suspicion and discrimination during the war, although prejudice and sheer numbers meant they suffered as a group generally less than Japanese Americans. The Alien Registration Act of 1940 required 300,000 German-born resident aliens who had German citizenship to register with the Federal government and restricted their travel and property ownership rights.[108][109] Under the still active Alien Enemy Act of 1798, the United States government interned nearly 11,000 German citizens between 1940 and 1948. Civil rights violations occurred.[110] An unknown number of "voluntary internees" joined their spouses and parents in the camps and were not permitted to leave.[111][112][113] Many Americans of German ancestry had top war jobs, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, and USAAF General Carl Andrew Spaatz. Roosevelt appointed Republican Wendell Willkie (who ironically ran against Roosevelt in the 1940 presidential election) as a personal representative. German Americans who had fluent German language skills were an important asset to wartime intelligence, and they served as translators and as spies for the United States.[114] The war evoked strong pro-American patriotic sentiments among German Americans, few of whom by then had contacts with distant relatives in the old country.[31][115]

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 1980[116] | |

| 1990[117] | |

| 2000[118] | |

| 2010[119] | |

| 2020[120] |

Contemporary period

editIn the aftermath of World War II, millions of ethnic Germans were forcibly expelled from their homes within the redrawn borders of Central and Eastern Europe, including the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary and Yugoslavia. Most resettled in Germany, but others came as refugees to the United States in the late 1940s, and established cultural centers in their new homes. Some Danube Swabians, for instance, ethnic Germans who had maintained language and customs after settlement in Hungary and the Balkans, immigrated to the U.S. after the war.

After 1970, the anti-German sentiment aroused by World War II faded away.[121] Today, German Americans who immigrated after World War II share the same characteristics as any other Western European immigrant group in the U.S.[122]

The German American community supported reunification in 1990.[123]

In the 1990 U.S. Census, 58 million Americans claimed to be solely or partially of German descent.[124] According to the 2005 American Community Survey, 50 million Americans have German ancestry. German Americans represent 17% of the total U.S. population and 26% of the non-Hispanic white population.[125]

The Economist magazine in 2015 interviewed Petra Schürmann, the director of the German-American Heritage Museum in Washington D.C. for a major article on German-Americans. She notes that all over the United States, celebrations such as German fests and Oktoberfests have been appearing.

Demographics

editStates with the highest proportions of German Americans tend to be those of the upper Midwest, including Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas; all at over 30%.[126]

Of the four major U.S. regions, German was the most-reported ancestry in the Midwest, second in the West, and third in both the Northeast and the South. German was the top reported ancestry in 23 states, and it was one of the top five reported ancestries in every state except Maine and Rhode Island.[126]

German-speakers and German-Americans of color

editDuring the 1800s, there were a number of German-speaking African-Americans, including Black Pennsylvania Dutch people. A few German-speaking African-Americans were Jewish. Some German-speaking African-Americans were adopted by white German-American families. Other Black German-Americans were immigrants from Germany. In the 1870 Census, 15 Black immigrants from Germany were listed living in New Orleans. Afro-German immigrants were also listed on the census living in Memphis, New York City, Charleston, and Cleveland.[127]

In Texas, many Tejanos have German ancestry.[128] Tejano culture, particularly Tejano music, has been deeply influenced by German immigrants to Texas and Mexico.[129] In German-speaking parts of Texas during the 19th and 20th centuries, many African-Americans spoke German. Many Black people who were enslaved by white German-Americans, as well as their descendants, learned to speak German.[130]

German American population by state

editAs of 2020, the distribution of German Americans across the 50 states and DC is as presented in the following table:

| State | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 303,109 | 6.19% |

| Alaska | 105,160 | 14.27% |

| Arizona | 913,671 | 12.74% |

| Arkansas | 279,279 | 9.27% |

| California | 2,786,161 | 7.08% |

| Colorado | 1,039,001 | 18.28% |

| Connecticut | 300,323 | 8.41% |

| Delaware | 116,569 | 12.05% |

| District of Columbia | 51,073 | 7.28% |

| Florida | 1,943,171 | 9.16% |

| Georgia | 669,497 | 6.37% |

| Hawaii | 82,087 | 5.78% |

| Idaho | 291,509 | 16.62% |

| Illinois | 2,175,044 | 17.10% |

| Indiana | 1,378,584 | 20.59% |

| Iowa | 1,016,154 | 32.26% |

| Kansas | 703,246 | 24.14% |

| Kentucky | 585,036 | 13.11% |

| Louisiana | 312,583 | 6.70% |

| Maine | 105,181 | 7.84% |

| Maryland | 728,155 | 12.06% |

| Massachusetts | 384,109 | 5.59% |

| Michigan | 1,849,636 | 18.54% |

| Minnesota | 1,753,612 | 31.31% |

| Mississippi | 143,117 | 4.80% |

| Missouri | 1,366,691 | 22.32% |

| Montana | 256,295 | 24.14% |

| Nebraska | 623,006 | 32.38% |

| Nevada | 303,225 | 10.01% |

| New Hampshire | 117,188 | 8.65% |

| New Jersey | 867,285 | 9.76% |

| New Mexico | 166,848 | 7.96% |

| New York | 1,809,206 | 9.27% |

| North Carolina | 997,739 | 9.61% |

| North Dakota | 280,834 | 36.93% |

| Ohio | 2,730,617 | 23.39% |

| Oklahoma | 483,973 | 12.25% |

| Oregon | 721,995 | 17.29% |

| Pennsylvania | 2,915,171 | 22.78% |

| Rhode Island | 53,192 | 5.03% |

| South Carolina | 471,940 | 9.27% |

| South Dakota | 314,246 | 35.74% |

| Tennessee | 612,083 | 9.04% |

| Texas | 2,429,525 | 8.48% |

| Utah | 326,656 | 10.37% |

| Vermont | 63,376 | 10.15% |

| Virginia | 876,286 | 10.30% |

| Washington | 1,177,478 | 15.67% |

| West Virginia | 282,257 | 15.62% |

| Wisconsin | 2,195,662 | 37.81% |

| Wyoming | 131,730 | 22.66% |

| United States | 42,589,571 | 13.04% |

German-American communities

editToday, most German Americans have assimilated to the point they no longer have readily identifiable ethnic communities, though there are still many metropolitan areas where German is the most reported ethnicity, such as Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, Milwaukee, Minneapolis – Saint Paul, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis.[132][133]

Communities with highest percentages of people of German ancestry

editThe 25 U.S. communities with the highest percentage of residents claiming German ancestry are:[134]

- Monterey, Ohio 83.6%

- Granville Township, Ohio 79.6%

- St. Henry, Ohio 78.5%

- Germantown Township, Illinois 77.6%

- Jackson, Indiana 77.3%

- Washington Township, Ohio 77.2%

- St. Rose, Illinois 77.1%

- Butler, Ohio 76.4%

- Marion Township, Ohio 76.3%

- Jennings, Ohio and Germantown, Illinois (village) 75.6%

- Coldwater, Ohio 74.9%

- Jackson, Ohio 74.6%

- Union, Ohio 74.1%

- Minster, Ohio and Kalida, Ohio 73.5%

- Greensburg, Ohio 73.4%

- Aviston, Illinois 72.5%

- Teutopolis, Illinois (village) 72.4%

- Teutopolis, Illinois (township) and Cottonwood, Minnesota 72.3%

- Dallas, Michigan 71.7%

- Gibson Township, Ohio 71.6%

- Town of Marshfield, Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin 71.5%

- Santa Fe, Illinois 70.8%

- Recovery Township, Ohio 70.4%

- Town of Brothertown, Wisconsin 69.9%

- Town of Herman, Dodge County, Wisconsin 69.8%

Large communities with high percentages of people of German ancestry

editLarge U.S. communities with a high percentage of residents claiming German ancestry are:[135]

- Bismarck, North Dakota 56.1%

- Dubuque, Iowa 43%

- St. Cloud, Minnesota 38.8%

- Fargo, North Dakota 31%

- Madison, Wisconsin 29%

- Green Bay, Wisconsin 29%

- Levittown, Pennsylvania 22%

- Erie, Pennsylvania 22%

- Cincinnati, Ohio 19.8%

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 19.7%

- Columbus, Ohio 19.4%

- Beaverton, Oregon 17%

Communities with the most residents born in Germany

editThe 25 U.S. communities with the most residents born in Germany are:[citation needed]

- Lely Resort, Florida 6.8%

- Pemberton Heights, New Jersey 5.0%

- Kempner, Texas 4.8%

- Cedar Glen Lakes, New Jersey 4.5%

- Alamogordo, New Mexico 4.3%

- Sunshine Acres, Florida and Leisureville, Florida 4.2%

- Wakefield, Kansas 4.1%

- Quantico, Virginia 4.0%

- Crestwood Village, New Jersey 3.8%

- Shandaken, New York 3.5%

- Vine Grove, Kentucky 3.4%

- Burnt Store Marina, Florida and Boles Acres, New Mexico 3.2%

- Allenhurst, Georgia, Security-Widefield, Colorado, Grandview Plaza, Kansas, and Fairbanks Ranch, California 3.0%

- Standing Pine, Mississippi 2.9%

- Millers Falls, Massachusetts, Marco Island, Florida, Daytona Beach Shores, Florida, Radcliff, Kentucky, Beverly Hills, Florida, Davilla, Texas, Annandale, New Jersey, and Holiday Heights, New Jersey 2.8%

- Fort Riley North, Kansas, Copperas Cove, Texas, and Cedar Glen West, New Jersey 2.7%

- Pelican Bay, Florida, Masaryktown, Florida, Highland Beach, Florida, Milford, Kansas, and Langdon, New Hampshire 2.6%

- Forest Home, New York, Southwest Bell, Texas, Vineyards, Florida, South Palm Beach, Florida, and Basye-Bryce Mountain, Virginia 2.5%

- Sausalito, California, Bovina, New York, Fanwood, New Jersey, Fountain, Colorado, Rye Brook, New York and Desoto Lakes, Florida 2.4%

- Ogden, Kansas, Blue Berry Hill, Texas, Lauderdale-by-the-Sea, Florida, Sherman, Connecticut, Leisuretowne, New Jersey, Killeen, Texas, White House Station, New Jersey, Junction City, Kansas, Ocean Ridge, Florida, Viola, New York, Waynesville, Missouri and Mill Neck, New York 2.3%

- Level Plains, Alabama, Kingsbury, Nevada, Tega Cay, South Carolina, Margaretville, New York, White Sands, New Mexico, Stamford, New York, Point Lookout, New York, and Terra Mar, Florida 2.2%

- Rifton, New York, Manasota Key, Florida, Del Mar, California, Yuba Foothills, California, Daleville, Alabama. Tesuque, New Mexico, Plainsboro Center, New Jersey, Silver Ridge, New Jersey and Palm Beach, Florida 2.1%

- Oriental, North Carolina, Holiday City-Berkeley, New Jersey, North Sea, New York, Ponce Inlet, Florida, Woodlawn-Dotsonville, Tennessee, West Hurley, New York, Littlerock, California, Felton, California, Laguna Woods, California, Leisure Village, New Jersey, Readsboro, Vermont, Nolanville, Texas, and Groveland-Big Oak Flat, California 2.0%

- Rotonda, Florida, Grayson, California, Shokan, New York, The Meadows, Florida, Southeast Comanche, Oklahoma, Lincolndale, New York, Fort Johnson South, Louisiana, and Townsend, Massachusetts 1.9%

- Pine Ridge, Florida, Boca Pointe, Florida, Rodney Village, Delaware, Palenville, New York, and Topsfield, Massachusetts 1.8%

Culture

editThe Germans worked hard to maintain and cultivate their language, especially through newspapers and classes in elementary and high schools. German Americans in many cities, such as Milwaukee, brought their strong support of education, establishing German-language schools and teacher training seminaries (Töchter-Institut) to prepare students and teachers in German language training. By the late 19th century, the Germania Publishing Company was established in Milwaukee, a publisher of books, magazines, and newspapers in German.[138]

"Germania" was the common term for German American neighborhoods and their organizations.[139] Deutschtum was the term for transplanted German nationalism, both culturally and politically. Between 1875 and 1915, the German American population in the United States doubled, and many of its members insisted on maintaining their culture. German was used in local schools and churches, while numerous Vereine, associations dedicated to literature, humor, gymnastics, and singing, sprang up in German American communities. German Americans tended to support the German government's actions, and, even after the United States entered World War I, they often voted for antidraft and antiwar candidates. 'Deutschtum' in the United States disintegrated after 1918.[140]

Music

editBeginning in 1741, the German-speaking Moravian Church Settlements of Bethlehem, Nazareth and Lititz, Pennsylvania, and Wachovia in North Carolina had highly developed musical cultures. Choral music, Brass and String Music and Congregational singing were highly cultivated. The Moravian Church produced many composers and musicians. Haydn's Creation had its American debut in Bethlehem in the early 19th century.

The spiritual beliefs of Johann Conrad Beissel (1690–1768) and the Ephrata Cloister—such as the asceticism and mysticism of this Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, group – are reflected in Beissel's treatises on music and hymns, which have been considered the beginning of America's musical heritage.[141]

In most major cities, Germans took the lead in creating a musical culture, with popular bands, singing societies, operas and symphonic orchestras.[142]

A small city, Wheeling, West Virginia could boast of 11 singing societies—Maennerchor, Harmonie, Liedertafel, Beethoven, Concordia, Liederkranz, Germania, Teutonia, Harmonie-Maennerchor, Arion, and Mozart. The first began in 1855; the last folded in 1961. An important aspect of Wheeling social life, these societies reflected various social classes and enjoyed great popularity until anti-German sentiments during World War I and changing social values dealt them a death blow.[143]

The Liederkranz, a German-American music society, played an important role in the integration of the German community into the life of Louisville, Kentucky. Started in 1848, the organization was strengthened by the arrival of German liberals after the failure of the revolution of that year. By the mid-1850s the Germans formed one-third of Louisville's population and faced nativist hostility organized in the Know-Nothing movement. Violent demonstrations forced the chorus to suppress publicity of its performances that included works by composer Richard Wagner. The Liederkranz suspended operations during the Civil War, but afterward grew rapidly, and was able to build a large auditorium by 1873. An audience of 8,000 that attended a performance in 1877 demonstrated that the Germans were an accepted part of Louisville life.[144]

The Imperial government in Berlin promoted German culture in the U.S., especially music. A steady influx of German-born conductors, including Arthur Nikisch and Karl Muck, spurred the reception of German music in the United States, while German musicians seized on Victorian Americans' growing concern with 'emotion'. The performance of pieces such as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony established German serious music as the superior language of feeling.[145]

Turners

editTurner societies in the United States were first organized during the mid-19th century so German American immigrants could visit with one another and become involved in social and sports activities. The National Turnerbund, the head organization of the Turnvereine, started drilling members as in militia units in 1854. Nearly half of all Turners fought in the Civil War, mostly on the Union side, and a special group served as bodyguards for President Lincoln.

By the 1890s, Turners numbered nearly 65,000. At the turn of the 21st century, with the ethnic identity of European Americans in flux and Americanization a key element of immigrant life, there were few Turner groups, athletic events were limited, and non-Germans were members. A survey of surviving groups and members reflects these radical changes in the role of Turner societies and their marginalization in 21st-century American society, as younger German Americans tended not to belong, even in strongholds of German heritage in the Midwest.[146]

Media

editAs for any immigrant population, the development of a foreign-language press helped immigrants more easily learn about their new home, maintain connections to their native land, and unite immigrant communities.[147] By the late 19th century, Germania published over 800 regular publications. The most prestigious daily newspapers, such as the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, the Anzeiger des Westens in St. Louis, and the Illinois Staats-Zeitung in Chicago, promoted middle-class values and encouraged German ethnic loyalty among their readership.[148] The Germans were proud of their language, supported many German-language public and private schools, and conducted their church services in German.[149] They published at least two-thirds of all foreign language newspapers in the U.S. The papers were owned and operated in the U.S., with no control from Germany. As Wittke emphasizes, press. it was "essentially an American press published in a foreign tongue". The papers reported on major political and diplomatic events involving Germany, with pride but from the viewpoint of its American readers.[150][151] For example, during the latter half of the 19th century, at least 176 different German-language publications began operations in the city of Cincinnati alone. Many of these publications folded within a year, while a select few, such as the Cincinnati Freie Presse, lasted nearly a century.[152] Other cities experienced similar turnover among immigrant publications, especially from opinion press, which published little news and focused instead on editorial commentary.[153]

By the end of the 19th century, there were over 800 German-language publications in the United States.[154] German immigration was on the decline, and with subsequent generations integrating into English-speaking society, the German language press began to struggle.[155] The periodicals that managed to survive in immigrant communities faced an additional challenge with anti-German sentiment during World War I[156] and with the Espionage and Sedition Acts, which authorized censorship of foreign language newspapers.[157] Prohibition also had a destabilizing impact on the German immigrant communities upon which the German-language publications relied.[155] By 1920, there were only 278 German language publications remaining in the country.[158] After 1945, only a few publications have been started. One example is Hiwwe wie Driwwe (Kutztown, PA), the nation's only Pennsylvania German newspaper, which was established in 1997.

Athletics

editGermans brought organized gymnastics to America, and were strong supporters of sports programs. They used sport both to promote ethnic identity and pride and to facilitate integration into American society. Beginning in the mid-19th century, the Turner movement offered exercise and sports programs, while also providing a social haven for the thousands of new German immigrants arriving in the United States each year. Another highly successful German sports organization was the Buffalo Germans basketball team, winners of 762 games (against only 85 losses) in the early years of the 20th century. These examples, and others, reflect the evolving place of sport in the assimilation and socialization of much of the German-American population.[159] Notable German Americans include Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, both native German speakers.

Religion

editGerman immigrants who arrived before the 19th century tended to have been members of the Evangelical Lutheran Churches in Germany, and created the Lutheran Synods of Pennsylvania, North Carolina and New York. The largest Lutheran denominations in the U.S. today—the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod—are all descended from churches started by German immigrants among others. Calvinist Germans founded the Reformed Church in the United States (especially in New York and Pennsylvania), and the Evangelical Synod of North America (strongest in the Midwest), which is now part of the United Church of Christ. Many immigrants joined different churches from those that existed in Germany. Protestants often joined the Methodist church.[31] In the 1740s, Count Nicolas von Zinzendorf tried to unite all the German-speaking Christians—(Lutheran, Reformed, and Separatists)—into one "Church of God in the Spirit". The Moravian Church in America is one of the results of this effort, as are the many "Union" churches in rural Pennsylvania.

Before 1800, communities of Amish, Mennonites, Schwarzenau Brethren and Moravians had formed and are still in existence today. The Old Order Amish and a majority of the Old Order Mennonites still speak dialects of German, including Pennsylvania German, informally known as Pennsylvania Dutch. The Amish, who were originally from southern Germany and Switzerland, arrived in Pennsylvania during the early 18th century. Amish immigration to the United States reached its peak between the years 1727 and 1770. Religious freedom was perhaps the most pressing cause for Amish immigration to Pennsylvania, which became known as a haven for persecuted religious groups.[160]

The Hutterites are another example of a group of German Americans who continue a lifestyle similar to that of their ancestors. Like the Amish, they fled persecution for their religious beliefs, and came to the United States between 1874 and 1879. Today, Hutterites mostly reside in Montana, the Dakotas, and Minnesota, and the western provinces of Canada. Hutterites continue to speak Hutterite German. Most are able to understand Standard German in addition to their dialect.[161] The German speaking "Russian" Mennonites migrated during the same time as the Hutterites, but assimilated relatively quickly in the United States, whereas groups of "Russian" Mennonites in Canada resisted assimilation.[162]

Immigrants from Germany in the mid-to-late-19th century brought many different religions with them. The most numerous were Lutheran or Catholic, although the Lutherans were themselves split among different groups. The more conservative Lutherans comprised the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod. Other Lutherans formed various synods, most of which merged with Scandinavian-based synods in 1988, forming the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.[163] Catholic Germans started immigrating in large numbers in the mid to latter 19th century, spurred in particular by the Kulturkampf.

Some 19th-century immigrants, especially the "Forty-Eighters", were secular, rejecting formal religion. About 250,000 German Jews had arrived by the 1870s, and they sponsored reform synagogues in many small cities across the country. About two million Central and Eastern European Jews arrived from the 1880s to 1924, bringing more traditional religious practices.[164]

Language

edit| Year | Speakers |

|---|---|

| 1910a | 2,759,032 |

| 1920a | 2,267,128 |

| 1930a | 2,188,006 |

| 1940a | 1,589,040 |

| 1960a | 1,332,399 |

| 1970a | 1,201,535 |

| 1980[165] | 1,586,593 |

| 1990[166] | 1,547,987 |

| 2000[167] | 1,383,442 |

| 2007[168] | 1,104,354 |

| 2011[169] | 1,083,637 |

| ^a Foreign-born population only[170] | |

After two or three generations, most German Americans adopted mainstream American customs – some of which they heavily influenced – and switched their language to English. As one scholar concludes, "The overwhelming evidence ... indicates that the German-American school was a bilingual one much (perhaps a whole generation or more) earlier than 1917, and that the majority of the pupils may have been English-dominant bilinguals from the early 1880s on."[171] By 1914, the older members attended German-language church services, while younger ones attended English services (in Lutheran, Evangelical and Catholic churches). In German parochial schools, the children spoke English among themselves, though some of their classes were in German. In 1917–18, after the American entry into World War I on the side of the Allies, nearly all German language instruction ended, as did most German-language church services.[105]

About 1.5 million Americans speak German at home, according to the 2000 census. From 1860 to 1917, German was widely spoken in German neighborhoods; see German in the United States. There is a false claim, called the Muhlenberg legend, that German was almost the official language of the U.S. There was never any such proposal. The U.S. has no official language, but use of German was strongly discouraged during World War I and fell out of daily use in many places.[172]

There were fierce battles in Wisconsin and Illinois around 1890 regarding proposals to stop the use of German as the primary language in public and parochial schools. The Bennett Law was a highly controversial state law passed in Wisconsin in 1889 that required the use of English to teach major subjects in all public and private elementary and high schools. It affected the state's many German-language private schools (and some Norwegian schools), and was bitterly resented by German American communities. The German Catholics and Lutherans each operated large networks of parochial schools in the state. Because the language used in the classroom was German, the law meant the teachers would have to be replaced with bilingual teachers, and in most cases shut down. The Germans formed a coalition between Catholics and Lutherans, under the leadership of the Democratic Party, and the language issue produced a landslide for the Democrats, as Republicans dropped the issue until World War I. By 1917, almost all schools taught in English, but courses in German were common in areas with large German populations. These courses were permanently dropped.[173]

Assimilation

editApparent disappearance of German American identity

editGerman Americans are no longer a conspicuous ethnic group.[174] As Melvin G. Holli puts it, "Public expression of German ethnicity is nowhere proportionate to the number of German Americans in the nation's population. Almost nowhere are German Americans as a group as visible as many smaller groups. Two examples suffice to illustrate this point: when one surveys the popular television scene of the past decade, one hears Yiddish humor done by comedians; one sees Polish, Greek, and East European detective heroes; Italian-Americans in situation comedies; and blacks such as the Jeffersons and Huxtables. But one searches in vain for quintessentially German-American characters or melodramas patterned after German-American experiences. ... A second example of the virtual invisibility is that, though German Americans have been one of the largest ethnic groups in the Chicago area (numbering near one-half million between 1900 and 1910), no museum or archive exists to memorialize that fact. On the other hand, many smaller groups such as Lithuanians, Poles, Swedes, Jews, and others have museums, archives, and exhibit halls dedicated to their immigrant forefathers".[175]: 93–94 [a]

But this inconspicuousness was not always the case. By 1910, German Americans had created their own distinctive, vibrant, prosperous German-language communities, referred to collectively as "Germania". According to historian Walter Kamphoefner, a "number of big cities introduced German into their public school programs".[177] Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Cleveland and other cities "had what we now call two-way immersion programs: school taught half in German, half in English".[177] This was a tradition which continued "all the way down to World War I".[177] According to Kamphoefner, German "was in a similar position as the Spanish language is in the 20th and 21st century"; it "was by far the most widespread foreign language, and whoever was the largest group was at a definite advantage in getting its language into the public sphere".[177] Kamphoefner has come across evidence that as late as 1917, a German version of "The Star-Spangled Banner" was still being sung in public schools in Indianapolis.[177]

Cynthia Moothart O'Bannon, writing about Fort Wayne, Indiana, states that before World War I "German was the primary language in the homes, churches and parochial schools"[178] of German American settlers. She states that "Many street signs were in German. (Main Street, for instance, was Haupt Strasse.) A large portion of local industry and commercial enterprises had at its roots German tooling and emigres. (An entire German town was moved to Fort Wayne when Wayne Knitting Mills opened.) Mayors, judges, firefighters and other community leaders had strong German ties. Social and sporting clubs and Germania Park in St. Joseph Township provided outlets to engage in traditional German activities".[178] She goes on to state that "The cultural influences were so strong, in fact, that the Chicago Tribune in 1893 declared Fort Wayne a 'most German town'."[178] Melvin G. Holli states that "No continental foreign-born group had been so widely and favorably received in the United States, or had won such high marks from its hosts as had the Germans before World War I. Some public opinion surveys conducted before the war showed German Americans were even more highly regarded than immigrants from the mother culture, England".[175]: 106 Holli states that the Chicago Symphony Orchestra once "had so many German-American musicians that the conductor often addressed them in the German language",[175]: 101 and he states that "No ethnic theater in Chicago glittered with such a classy repertory as did the German-American theater, or served to introduce so many European classical works to American audiences".[175]: 102

Impact of World War I

editThe transition to the English language was abrupt, forced by federal, state and local governments, and by public opinion, when the U.S. was at war with Germany in 1917–18. After 1917, the German language was seldom heard in public; most newspapers and magazines closed; churches and parochial schools switched to English. Melvin G. Holli states, "In 1917, the Missouri Synod's Lutheran Church conference minutes appeared in English for the first time, and the synod's new constitution dropped its insistence on using the language of Luther only and instead suggested bilingualism. Dozens of Lutheran schools also dropped instruction in the German language. English-language services also intruded themselves into parishes where German had been the lingua franca. Whereas only 471 congregations nationwide held English services in 1910, the number preaching in English in the synod skyrocketed to 2,492 by 1919. The German Evangelical Synod of Missouri, Ohio, and other states also anglicized its name by dropping German from the title".[175]: 106 Writing about Fort Wayne, Indiana, Cynthia Moothart O'Bannon states that, in the First World War, "Local churches were forced to discontinue sermons in German, schools were pressured to stop teaching in German, and the local library director was ordered to purchase no more books written in German. The library shelves also were purged of English-language materials deemed sympathetic to or neutral on Germany. Anti-German sentiment forced the renaming of several local institutions. Teutonia Building, Loan & Savings became Home Loan & Savings, and The German-American bank became Lincoln National Bank & Trust Co."[178] She continues that "in perhaps the most obvious bend to prevailing trends, Berghoff Brewery changed its motto from "A very German brew" to "A very good brew," according to "Fort Wayne: A Most German Town," a documentary produced by local public television station WFWA, Channel 39".[178] Film critic Roger Ebert wrote how "I could hear the pain in my German-American father's voice as he recalled being yanked out of Lutheran school during World War I and forbidden by his immigrant parents ever to speak German again".[179]

Melvin G. Holli states, regarding Chicago, that "After the Great War it became clear that no ethnic group was so de-ethnicized in its public expression by a single historic event as German Americans. While Polish Americans, Lithuanian Americans, and other subject nationalities underwent a great consciousness raising, German ethnicity fell into a protracted and permanent slump. The war damaged public expression of German ethnic, linguistic, and cultural institutions almost beyond repair".[175]: 106 He states that, after the war, German ethnicity "would never regain its prewar public acclaim, its larger-than-life public presence, with its symbols, rituals, and, above all, its large numbers of people who took pride in their Teutonic ancestry and enjoyed the role of Uncle Sam's favored adopted son".[175]: 107 He states "A key indicator of the decline of "Deutschtum" in Chicago was the census: the number identifying themselves to the census-taker as German-born plummeted from 191,000 in 1910 to 112,000 in 1920. This drop far exceeds the natural mortality rate or the number who might be expected to move. Self-identifiers had found it prudent to claim some nationality other than German. To claim German nationality had become too painful an experience".[175]: 106 Along similar lines, Terrence G. Wiley states that, in Nebraska, "around 14 percent of the population had identified itself as being of German-origin in 1910; however, only 4.4 percent made comparable assertions in 1920. In Wisconsin, the decline in percentage of those identifying themselves as Germans was even more obvious. The 1920 census reported only 6.6. percent of the population as being of German-origin, as opposed to nearly 29 percent ten years earlier ... These statistics led Burnell ... to conclude that: "No other North American ethnic group, past or present, has attempted so forcefully to officially conceal their ... ethnic origins. One must attribute this reaction to the wave of repression that swept the Continent and enveloped anyone with a German past"".[180]

The Catholic high schools were deliberately structured to commingle ethnic groups so as to promote ethnic (but not interreligious) intermarriage.[181] German-speaking taverns, beer gardens and saloons were all shut down by Prohibition; those that reopened in 1933 spoke English.

Impact of World War II

editWhile its impact appears to be less well-known and studied than the impact which World War I had on German Americans, World War II was likewise difficult for them and likewise had the impact of forcing them to drop distinctive German characteristics and assimilate into the general U.S. culture.[182][183] According to Melvin G. Holli, "By 1930, some German American leaders in Chicago felt, as Dr. Leslie Tischauser put it, 'the damage done by the wartime experience had been largely repaired'. The German language was being taught in the schools again; the German theater still survived; and German Day celebrations were drawing larger and larger crowds. Although the assimilation process had taken its toll of pre-1914 German immigrants, a smaller group of newer postwar arrivals had developed a vocal if not impolitic interest in the rebuilding process in Germany under Nazism. As the 1930s moved on, Hitler's brutality and Nazi excesses made Germanism once again suspect. The rise of Nazism, as Luebke notes, 'transformed German ethnicity in America into a source of social and psychological discomfort, if not distress. The overt expression of German-American opinion consequently declined, and in more recent years, virtually disappeared as a reliable index of political attitudes ...'"[175]: 108

Holli goes on to state that "The pain increased during the late 1930s and early 1940s, when Congressman Martin Dies held public hearings about the menace of Nazi subversives and spies among the German Americans. In 1940, the Democratic party's attack on anti-war elements as disloyal and pro-Nazi, and the advent of the war itself, made German ethnicity too heavy a burden to bear. As Professor Tischauser wrote, "The notoriety gained by those who supported the German government between 1933 and 1941 cast a pall over German-Americans everywhere. Leaders of the German-American community would have great difficulty rebuilding an ethnic consciousness ... Few German-Americans could defend what Hitler ... had done to millions of people in pursuit of the 'final solution', and the wisest course for German-Americans was to forget any attachment to the German half of their heritage.""[175]: 108–109

A notable example which highlights the generational effect of this de-germanization on German-American cultural identity is U.S. President Donald Trump's erroneous assertion of Swedish heritage as late as 1987 in The Art of the Deal.[184][185][186] This error stems from Donald Trump's father, Fred Trump, who was of German heritage but attempted to pass himself off as Swedish amid the anti-German sentiment sparked by World War II, a claim which would continue to mislead his family for decades.[184]

By the 1940s, Germania had largely vanished outside some rural areas and the Germans were thoroughly assimilated.[187] According to Melvin G. Holli, by the end of World War II, German Americans "were ethnics without any visible national or local leaders. Not even politicians would think of addressing them explicitly as an ethnic constituency as they would say, Polish Americans, Jewish Americans, or African Americans."[175]: 109 Holli states that "Being on the wrong side in two wars had a devastating and long-term negative impact on the public celebration of German-American ethnicity".[175]: 106

Historians have tried to explain what became of the German Americans and their descendants. Kazal (2004) looks at Germans in Philadelphia, focusing on four ethnic subcultures: middle-class Vereinsdeutsche, working-class socialists, Lutherans, and Catholics. Each group followed a somewhat distinctive path toward assimilation. Lutherans, and the better situated Vereinsdeutsche with whom they often overlapped, after World War I abandoned the last major German characteristics and redefined themselves as old stock or as "Nordic" Americans, stressing their colonial roots in Pennsylvania and distancing themselves from more recent immigrants. On the other hand, working-class and Catholic Germans, groups that heavily overlapped, lived and worked with Irish and other European ethnics; they also gave up German characteristics but came to identify themselves as White ethnics, distancing themselves above all from African American recent arrivals in nearby neighborhoods. Well before World War I, women in particular were becoming more and more involved in a mass consumer culture that lured them out of their German-language neighborhood shops and into English-language downtown department stores. The 1920s and 1930s brought English-language popular culture via movies and radio that drowned out the few surviving German language venues.[188]

Factors favoring assimilation

editKazal points out that German Americans have not had an experience that is especially typical of immigrant groups. "Certainly, in a number of ways, the German-American experience was idiosyncratic. No other large immigrant group was subjected to such strong, sustained pressure to abandon its ethnic identity for an American one. None was so divided internally, a characteristic that made German Americans especially vulnerable to such pressure. Among the larger groups that immigrated in the country after 1830, none – despite regional variations – appears to have muted its ethnic identity to so great an extent."[188]: 273 This quote from Kazal identifies both external pressures on German Americans and internal dividedness among them as reasons for their high level of assimilation.

Regarding the external pressures, Kazal writes: "The pressure imposed on German Americans to forsake their ethnic identity was extreme in both nature and duration. No other ethnic group saw its 'adoptive fatherland' twice enter a world war against its country of origin. To this stigma, the Third Reich added the lasting one of the Holocaust. In her study of ethnic identity in the 1980s, sociologist Mary Waters noted that the 'effect of the Nazi movement and World War II was still quite strong' in shaping 'popular perceptions of the German-American character', enough so that some individuals of mixed background often would acknowledge only the non-German part of their ancestry."[188]: 273 [b] Kazal contrasts this experience with the experiences of the Japanese, Poles, Czechs, Lithuanians, Italians, east European Jews, and Irish. "Japanese Americans, of course, suffered far more during the Second World War",[188]: 273 but until at least the 1950s, the pressure on Japanese Americans "ran toward exclusion from, rather than inclusion in, the nation".[188]: 273 "The state and many ordinary European Americans refused to recognize Asians as potentially American. In contrast, they pressured Germans to accept precisely that American identity in place of a German one".[188]: 273