George Cook (1772–1845) was a Scottish minister, author of religious tracts and professor of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews University. He served as Moderator of the Church of Scotland in 1825. He was the leader of the "moderate" party in the church of Scotland on the question of the Veto Act, which led to Disruption of 1843 and the formation of the Free Church by the "evangelical party.[2][3]

George Cook | |

|---|---|

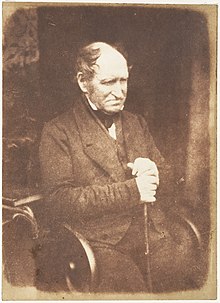

George Cook by Hill & Adamson | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Cook 22 March 1772 |

| Died | 13 May 1845 (aged 73) |

| minister of Laurencekirk | |

| In office 3 September 1795 – 16 November 1828 | |

| Professor of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews | |

| In office 10 June 1829 – 13 May 1845 | |

| Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland[1] | |

| In office May 1825 – May 1826 | |

Professional life

editHe was born on 22 March 1772 in Newburn, Fife the son of John Cook (1739–1815) and Janet Hill. His mother was the sister of George Hill and daughter of John Hill, minister of St Andrews. George Cook studied at St Andrews University graduating from MA in 1790. He received a licence to minister on 30 April 1795 and the following year took over in the parish of Laurencekirk where he was ordained on 3 September 1795. In 1829 he was offered the Chair of Moral Philosophy at St Andrews University (a post held by his father from 1773 until 1802) where he continued until death in 1845.[3]

Academic studies

editIn 1808 he published An Illustration of the General Evidence establishing the Reality of Christ's Resurrection, and the same year received the degree of D.D. from St. Andrews University. Subsequently he devoted his leisure specially to the study of the constitution and history of the church of Scotland, and in 1811 published History of the Reformation in Scotland, 3 vols., which was followed in 1815 by the History of the Church of Scotland, in 3 vols., embracing the period from the regency of Moray to the revolution. His style of narrative is somewhat cold and frigid, but it is generally characterised by lucidity and accuracy. In 1820 he published the Life of Principal Hill, who was his maternal uncle, and in 1822, General and Historical View of Christianity.[2]

Church courts

editFrom an early period Cook took a prominent part in the deliberations of the general assembly, and on the death of his uncle, Principal Hill, in 1819, virtually succeeded him as leader of the "moderate" party. Having, however, in opposition to the general views of the party, taken a decided stand against "pluralities" and "non-residence"—regarding which he published in 1816 the substance of a speech delivered in the general assembly—he was for some time viewed by many of the party with considerable distrust, and when he was proposed as moderator in 1821 and 1822, he was defeated on both occasions by large majorities.[2] In 1825, during his term at Laurencekirk, he was elected Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.[4] He was unanimously elected in 1825, and from this time was accepted as the unchallenged leader of the party, guiding both privately and publicly their policy in regard to the constitutional questions arising out of the Veto Act of 1834, passed in opposition to his party against intrusion. In 1829 Cook demitted his charge at Laurencekirk on being chosen professor of moral philosophy in the United College, St. Andrews, but this made no change in his relation to the church of Scotland, and he was annually chosen a representative to the general assembly. In 1834 he published A few plain Observations on the Enactments of the General Assembly of 1834 relating to Patronage and Calls, and in the ten years' conflict on the subject which followed gave a persistent and strenuous opposition to the policy of the "evangelical" party led by Thomas Chalmers. Though unable to cope with Chalmers and others in brilliant or popular oratory, he possessed great readiness of reply, while his calm judgment, clear and logical exposition and accurate knowledge of the laws and constitution of the church enabled him to hold his own, so far as technical argument, apart from appeal to sentiment and popular feelings, was concerned. He did not long survive the disruption of 1843. Shortly after the assembly of 1844 he was attacked by heart disease, and he died suddenly at St. Andrews 13 May 1845.[2]

Other interests

editHe was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1816, his proposer being John Playfair. Cook's father was a co-founder of the Society.

Death and legacy

editHe died in St Andrews on 13 May 1845 and is buried there with his mother within St Regulus Chapel (St Rule's Tower) in the churchyard of St Andrews Cathedral next to Robert Chambers.

Publications

edit- An Illustration of the General Evidence establishing the Reality of Christ's Resurrection (Newcastle, 1808 and 1826)

- History of the Reformation in Scotland, 3 vols. (Edinburgh, 1811)

- History of the Church of Scotland, 3 vols. (Edinburgh, 1815)

- A Speech respecting Residence and Pluralities (Edinburgh, 1816)

- Life of George Hill, D.D. (Edinburgh, 1820)

- A General and Historical View of Christianity, 3 vols. (Edinburgh, 1822)

- A Speech relating to the Appointment of Ministers (Dundee, 1833)

- A few Plain Observations on the Enactments of the General Assembly of 1834, relating to Patronage and Calls (Edinburgh, 1834, 2nd ed. to which are now added some Supplementary Remarks, 1835)

- A Brief Synopsis of a Course of Lectures on Intellectual, Moral, and Political Philosophy (Edinburgh, 1837)

- A Manual of Political Economy (Edinburgh, 1837)

- A Speech delivered in the General Assembly, 23 May 1838, on the Overtures relating to the Spiritual Independence of the Church (Edinburgh, 1838)

- A Speech on the Auchterarder Case (Edinburgh, 1839)

- Memorial submitted to Her Majesty's Government by ... G. Cook, D.D., and a Committee (Edinburgh, 1842)

- A Speech delivered in the General Assembly, 24 May 1843, introducing a Motion in relation to the Ministers and Elders who have withdrawn from the Established Church (Edinburgh, 1843).[3]

Family

editHe married 23 February 1801, Diana, youngest daughter of Alexander Shank, minister of St Cyrus, and had issue —

- Diana, born 18 May 1802, died 8 April 1817

- Janet, born 27 March, died 2 April 1805

- John, minister of Haddington, born 12 September 1807, who was Moderator 1866/67[1]

- Mary, born 21 May 1809 (married Thomas Marjoribanks, minister of Stenton)

- Alexander Shank, advocate, Procurator of the Church, born 9 December 1810, died 16 January 1869

- George Cook, minister of Borgue, born 11 June 1812, Moderator in 1876/77.[1]

- Henry David, H.E.I.C.S., born 19 May 1814, died 1882.[1]

His mother was Janet Hill and her brothers included George Hill (1750–1819) and John Hill (1747–1805). For a fuller family tree see Cook.[5]

| Cook Hill family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John Hill | George Hill | Janet Hill | John Cook (1739–1815) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alexander Hill | Elisabeth Hill | John Cook (moderator 1816) | George Cook (1772–1845) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John Cook (1807–1869) | John Cook (Haddington)(1807–1874) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rachel Cook | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d Scott 1928.

- ^ a b c d Henderson 1887.

- ^ a b c Scott 1925.

- ^ Fraser 1880.

- ^ Cook 2013.

Sources

edit- Anderson, William (1877). "Cook, George D.D.". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. Vol. 1. A. Fullarton & co. pp. 680-682. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Brown, Stewart J. (2004). "Cook, George(1772–1845)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6137. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Buchanan, Robert (1849a). The ten years' conflict; being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Blackie.

- Buchanan, Robert (1849b). The ten years' conflict; being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Blackie.

- Cook, Diana Helen (2013). "family tree". Change and Transition in a Professional Scots Family 1650-1900 (MPhil). University of Dundee. p. 143.

- Fraser, William Ruxton (1880). History of the parish and burgh of Laurencekirk. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. pp. 237-242.

- Gordon, Alexander (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 72. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 12. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 72. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Scott, Hew (1925). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 5. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 477-478. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Scott, Hew (1928). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 7. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. p. 444. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Sefton, Henry R. (1991). St Mary's College, St Andrews in the eighteenth century. Edinburgh: Scottish Church History Society. p. 180.