Genoa Washington (born 1895 or 1896; died October 14, 1972) was an American politician who served in the Illinois House of Representatives from 1967 until his death in 1972. A Republican member from Chicago, he worked on legislation related to civil rights and women's rights. Washington ran unsuccessfully for the US House of Representatives in 1954 and 1960. He also served as alternate US delegate to the United Nations General Assembly in 1957, and as delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1952, 1964, and 1968.

Genoa Washington | |

|---|---|

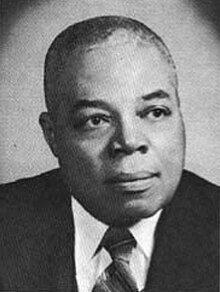

Washington in 1967–1968 | |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 22nd district | |

| In office 1967–1972 | |

| Preceded by | At-large representation |

| Succeeded by | Susan Catania (Republican representative of multi-member district) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1895 or 1896 Washington, D.C., US |

| Died | (aged 76) Chicago, Illinois, US |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | Northwestern University (BS, JD) |

Washington earned his Bachelor of Science degree and Juris Doctor at Northwestern University. He later held positions as vice president of the Cook County Bar Association, and as president of the Chicago branch of the NAACP. He served in the US Army and was involved in Freemason organizations.

Personal life and early career

editGenoa Washington was born in 1895 or 1896[note 1] in Washington, D.C. He was the oldest of three children and the only son. His parents were Virgil William Washington, a Methodist minister and general secretary of missions at the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, and Lucy Virginia Bonner. The younger Washington attended primary and secondary schools wherever his father's work took the family. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree and Juris Doctor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1929. Washington served as vice president of the Cook County Bar Association, and as president of the Chicago branch of the NAACP. He was enlisted in the US Army as a private and was discharged as a captain of infantry. As a Freemason, Washington was a member of the Scottish Rite, affiliated with Prince Hall Freemasonry, and a master of the Richard E. Moore Lodge.[3][4]

Non-legislative political career

editWashington served as an alternate delegate during the 1952 Republican National Convention. He was the only member of the Illinois delegation to vote for Dwight D. Eisenhower; the rest voted for Robert A. Taft.[5] During the 1954 US House elections, Washington ran to represent Illinois's 1st congressional district, winning the Republican primary[6] but losing the general election to the Democratic incumbent, William L. Dawson.[7]

Eisenhower, by then elected president, appointed Washington as alternate American delegate to the Twelfth session of the United Nations General Assembly in 1957,[3][8] where he served on the Special Political Committee.[4] Eisenhower ended up appointing eight African Americans as alternate representatives to the UN, surpassing his Democratic predecessor, Harry S. Truman, who had appointed only three.[8]

Washington then ran again in the 1960 US House elections for the 1st district. In the Republican primary, he ran against James M. Burr, who previously had sought the nomination unsuccessfully in 1958.[5] Washington won the Republican primary[9] but again lost the general election to Dawson.[10] During the 1964 Republican National Convention, Washington and Euclid Taylor, a Chicago-based attorney, served as the only two African American delegates from Illinois, representing the 1st congressional district. Even though both were pledged to Nelson Rockefeller, Washington stated during a closed caucus meeting that he had wanted to vote for the eventual nominee, Barry Goldwater, to show unity.[11][12] During the convention, Washington gave one of the speeches seconding Rockefeller's nomination.[13] He and Taylor joined two other Illinois delegates in supporting a proposal by William Scranton, governor of Pennsylvania, which would have modified the Republican platform to call for strengthening federal enforcement of civil rights legislation. Scranton's proposal failed at the convention.[14] At the next Republican National Convention in 1968, Washington again supported Rockefeller for the presidential nomination, while most of the Illinois delegation backed Richard Nixon.[15] Washington was also one of two Illinois delegates who abstained on the vice presidential ballot, declining to support Spiro Agnew.[16]

Illinois House of Representatives

editWashington was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1966. He represented the 22nd district, reclaiming a seat that Democrats had taken control of in 1964.[note 2][18][4] From 1967 through 1972 he worked on bills related to civil rights and women's rights.[3] Washington supported a fair housing proposal in 1967 that prohibited real estate brokers from refusing to sell or rent African Americans, but it contained an exception when the property owners explicitly consented to the discrimination. Washington did not believe the legislature would pass a bill prohibiting discrimination by homeowners, as such a proposal would have been seen as "forced housing".[19] In 1969, he and other Black members of the House filibustered an appropriations bill for the Illinois Department of Conservation to secure funding for recruitment and job training of minorities.[20] In 1972, Washington sponsored an emergency appropriations bill directing $19 million to public aid.[21]

During his campaign for reelection in 1972, Washington faced three challengers for the Republican nomination, including Susan Catania, a freelance technical publications consultant. The Chicago Tribune reported that Catania was running "one of the most vigorous campaigns of the year", in contrast to the other candidates. Washington was confident of his reelection and led a relatively quiet campaign.[1]

Washington had cancer and did not survive the election season, dying in his home on October 14, 1972, at age 76. Catania succeeded him as the Republican representative from their district.[note 3][2][25]

Notes

edit- ^ Washington stated in early 1972 that he was in his 70s but unsure of his exact age, having lost his birth records.[1] When he died later that year, his obituary said that he was 76.[2]

- ^ Due to the state's failure to redistrict, the 1964 Illinois House of Representatives election was an at-large election. All of the Democratic candidates won, taking control of the House from Republicans. As a result, 35 Republicans lost their seats, including Elwood Graham of the 22nd district.[17] New legislative maps were approved for the 1966 elections.

- ^ Each district elected three members to the House, through a system of cumulative voting meant to encourage bipartisanship.[22] This guaranteed that the 22nd district would elect one Republican member, despite being predominantly Democratic.[23][24]

References

edit- ^ a b Seslar, Thomas (March 12, 1972). "Woman Overshadows Foes in 22d District Race". Chicago Tribune. sec. 10, p. 1. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Obituaries: Genoa Washington". Chicago Tribune. October 18, 1972. sec. 3, p. 16. Archived from the original on January 18, 2024. Retrieved January 17, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Brooks Williams, Erma (2008). Political Empowerment of Illinois' African-American State Lawmakers from 1877 to 2005. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780761840183. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ a b c Powell, Paul, ed. (1967–1968). Illinois Blue Book, 1967–1968. Illinois Secretary of State. p. 235. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Wood, Percy (March 13, 1960). "See Hot Primary in 4th District: But Other Races Appear Dull". Chicago Tribune. part 3, p. 12. Archived from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Howard, Robert (April 15, 1954). "All 25 Illinois Congressmen Win in Primary". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rockwood, Earl; Roberts, Ralph R. (October 15, 1955). Statistics of the Congressional Election of November 2, 1954 (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office (published 1956). p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Krenn, Michael (1999). Black Diplomacy: African Americans and the State Department, 1945–69. New York: Routledge (published May 20, 2015). ISBN 9781317475811. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Yalowitz, Gerson (April 14, 1960). "Seven Congressmen Renominated in Illinois". Mt. Vernon Register-News. Associated Press. p. 13. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Guthrie, Benjamin J.; Roberts, Ralph R. (April 15, 1961). Statistics of the Presidential and Congressional Election of November 8, 1960 (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office (published 1961). p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "Deny Entire Ill. GOP Delegation Pro-Goldwater". Jet. XXVI (11). Chicago: Johnson Publishing Co.: 5. June 25, 1964. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Tagge, George (July 15, 1964). "Illinois Gives Barry 56 of 58". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Whalen, Charles (July 16, 1964). "Goldwater Expected in Illinois". Alton Evening Telegraph. Associated Press. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Whalen, Charles (July 15, 1964). "4 Illinoisans Back Rights Plank Change; 54 Hold Line". The Southern Illinoisan. Carbondale, Illinois. Associated Press. p. 5. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tagge, George (August 1, 1968). "Dirksen Set to Declare for Nixon". Chicago Tribune. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Johnson, Ralph H. (August 9, 1968). "Revolt smothered, Illinois delegates back Agnew". The Southern Illinoisan. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 18, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tagge, George (December 4, 1964). "35 in G.O.P. Lose State House Seats". Chicago Tribune. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 12, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Booker, Simeon (November 24, 1966). "Election Conclusions: Negroes". Jet. XXXI (7). Chicago: Johnson Publishing Co.: 10. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ "Fair Housing Bills Introduced by GOP". Jacksonville Daily Journal. Associated Press. March 3, 1967. p. 10. Archived from the original on January 21, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Icen, Richard (June 30, 1969). "Black Legislators Cohesive". Edwardsville Intelligencer. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lauk, Tom (May 26, 1972). "Emergency public aid bill goes to Governor Ogilvie". Daily Republican-Register. Mount Carmel, Illinois. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McDowell, James L. (2007). "The Orange-Ballot Election: The 1964 Illinois At-Large Vote—and After". Journal of Illinois History. 10: 291. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ Catania, Susan; Haynes, Judy (1984). Susan Catania Memoir. Springfield, Illinois: University of Illinois Board of Trustees. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ "Catania to teach course at SSU". Illinois Issues. University of Illinois at Springfield: 40. February 1984. ISSN 0738-9663. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2021 – via Illinois Periodicals Online.

- ^ Padar, Kayleigh (December 14, 2023). "Former Republican Illinois legislator Susan Catania remembered for supporting gay rights". Windy City Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2024.