Mughal Gardens are a type of garden built by the Mughals. This style was influenced by the Persian gardens particularly the Charbagh structure,[1] which is intended to create a representation of an earthly utopia in which humans co-exist in perfect harmony with all elements of nature.[2]

Significant use of rectilinear layouts are made within the walls enclosures. Some of the typical features include pools, fountains and canals inside the gardens. Afghanistan, Bangladesh and India have a number of gardens which differ from their Central Asian predecessors with respect to "the highly disciplined geometry".

History

editThe founder of the Mughal empire, Babur, described his favourite type of garden as a charbagh. The term bāgh, baug, bageecha or bagicha is used for the garden. This word developed a new meaning in South Asia, as the region lacked the fast-flowing streams required for the Central Asian charbagh. The Aram Bagh of Agra is thought to have been the first charbagh in South Asia.

From the beginnings of the Mughal Empire, the construction of gardens was a beloved imperial pastime.[3] Babur, the first Mughal conqueror-king, had gardens built in Lahore and Dholpur. Humayun, his son, does not seem to have had much time for building—he was busy reclaiming and increasing the realm—but he is known to have spent a great deal of time at his father's gardens.[4] Akbar built several gardens first in Delhi,[5] then in Agra, Akbar's new capital.[6] These tended to be riverfront gardens rather than the fortress gardens that his predecessors built. Building riverfront rather than fortress gardens influenced later Mughal garden architecture considerably.

Akbar's son, Jahangir, did not build as much, but he helped to lay out the famous Shalimar garden and was known for his great love for flowers.[7] His trips to Kashmir are believed to have begun a fashion for naturalistic and abundant floral design.[8]

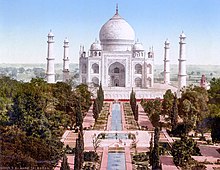

Jahangir's son, Shah Jahan, marks the apex of Mughal garden architecture and floral design. He is famous for the construction of the Taj Mahal, a sprawling funereal paradise in memory of his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal.[9] He is also responsible for the Red Fort at Delhi and the Mahtab Bagh, a night garden that was filled with night-blooming jasmine and other pale flowers, located opposite the Taj across the Yamuna river at Agra.[10] The pavilions within are faced with white marble to glow in the moonlight. This and the marble of the Taj Mahal are inlaid with semiprecious stone depicting scrolling naturalistic floral motifs, the most important being the tulip, which Shah Jahan adopted as a personal symbol.[11]

Gol Bagh was the largest recorded garden of the Indian subcontinent,[12] encompassing the town of Lahore with a five-mile belt of greenery;[13] it existed until as late as 1947.[13] The initiator of the Mughal gardens in India was Zaheeruddin Babur who had witnessed the beauty of Timurid gardens in Central Asia during his early days. In India, Babur laid out the gardens more systematically. Fundamentally, the Mughal gardens have had edifices in a symmetrical arrangement within enclosed towns with provisions for water channels, cascades, water tanks and fountains etc. Thus, the Mughals maintained the tradition of building fourfold (chaharbagh)-symmetrical garden. Babur, however, applied the term chaharbagh in its widest sense which includes terraced gardens on mountain slopes and his extravagant rock cut garden, the Bagh-i Nilufar at Dholpur.

After Babur, the tradition of building chaharbagh touched its zenith during the time of Shah Jahan. However, modern scholars are now increasingly questioning the excessive use of the term chaharbagh in the interpretation of Mughal gardens, since it was not always symmetrical. This view finds archaeological support also. The excavated Mughal garden at Wah (12 km west of Taxila), near Hasan Abdal, associated with Mughal emperors Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan reveals that the pattern and overall design has not been symmetrical on the first and second terraces.

As for location, the Mughal emperors were much particular in selecting places of great natural beauty. Often they selected mountain slopes with gushing water to layout gardens, the finest example being Bagh-i Shalimar and Bagh-i Nishat in Kashmir.

Almost all the Mughal gardens contained buildings such as residential palaces, forts, mausoleums, and mosques. The gardens became an essential feature of almost each kind of Mughal monuments and were interrelated to these monuments which can be categorized as: (i) gardens attached with Imperial palaces, forts and gardens which beautified private residential buildings of the nobles (ii) Religious and sacred structures i.e., tombs and mosques erected in the gardens, and (iii) Resort and public building in the pleasure gardens.

Waterworks

editLike Persian and Central Asian gardens, water became the central and connecting theme of the Mughal gardens. Water played an effective role in the Mughal gardens right from the time of Babur. He was more interested in 'beauty' than 'ecclesiastical prescription. The beauty of Babur's classic chaharbagh was the central watercourse and its flowing water. Most of these gardens were divided into four quadrants by two axis comprised with water channels and pathways to carry the water under gravitational pressure. At every intersecting point, there used to be a tank. In India, the early gardens were irrigated from the wells or tanks, but under the Mughals the construction of canals or the use of existing canals for the gardens provided more adequate and dependable water supply. Thus, the most important aspect of the waterworks of gardens was the permanent source of water supply. The hydraulic system needs enquiry about the 'outside water source' as well as 'inside distribution of water' in the paradisiacal Mughal gardens. The principal source of water to the Mughal gardens were: (i) lakes or tanks (ii) wells or step-wells (iii) canals, harnessed from the rivers, and (iv) natural springs.

The fountain was the symbol of 'life cycle' which rises and merges and rises again. The Paradise possessed two fountains: 'salsabil' and 'uyun'. 131 Salih Kambuh, a native of Lahore, described very artistically the water system and its symbolic meaning in the garden of Shalamar at Lahore that 'in the center of this earthly paradise a sacred stream flows with its full elegance and chanting, fascinating and exhilarating nature and passes through the gardens irrigating the flower beds. Its water is as beautiful as greenery. The vast stream is just like clouds pouring rains and opens the doors of divine mercy. Its chevron patterns (abshar) are like an institution of worship where the hearts of believers are enlightened. The Mughals developed hydraulic system by using Persian wheel to lift the water and obtained adequate pressure necessary for gardens. The main reason behind the location of gardens on the bank of river was that water was raised to the level of the enclosure wall by Persian Wheel standing on the bank from where it was conducted through aqueduct, to the garden where it ran from the top of the wall in a terra-cotta pipe which also produced adequate pressure needed to work the fountains.[14]

Design and symbolism

editMughal gardens design derives primarily from the medieval Islamic garden, although there are nomadic influences that come from the Mughals' Turkic-Mongolian ancestry as well as inherent elements from Ancient Persia. Julie Scott Meisami describes the medieval Islamic garden as "a hortus conclusus, walled off and protected from the outside world; within, its design was rigidly formal, and its inner space was filled with those elements that man finds most pleasing in nature. Its essential features included running water (perhaps the most important element) and a pool to reflect the beauties of sky and garden; trees of various sorts, some to provide shade merely, and others to produce fruits; flowers, colorful and sweet-smelling; grass, usually growing wild under the trees; birds to fill the garden with song; the whole is cooled by a pleasant breezes.

The garden might include a raised hillock at the center, reminiscent of the mountain at the center of the universe in cosmological descriptions, and often surmounted by a pavilion or palace."[16] The Turkish-Mongolian elements of the Mughal garden are primarily related to the inclusion of tents, carpets and canopies reflecting nomadic roots. Tents indicated status in these societies, so wealth and power were displayed through the richness of the fabrics as well as by size and number.[17]

Fountainry and running water was a key feature of Mughal garden design. Water-lifting devices like geared Persian wheels (saqiya) were used for irrigation and to feed the water-courses at Humayun's Tomb in Delhi, Akbar's Gardens in Sikandra and Fatehpur Sikhri, the Lotus Garden of Babur at Dholpur and the Shalimar Bagh in Srinagar. Royal canals were built from rivers to channel water to Delhi, Fatehpur Sikhri and Lahore. The fountains and water-chutes of Mughal gardens represented the resurrection and regrowth of life, as well as to represent the cool, mountainous streams of Central Asia and Afghanistan that Babur was famously fond of. Adequate pressure on the fountains was applied through hydraulic pressure created by the movement of Persian wheels or water-chutes (chaadar) through terra-cotta pipes, or natural gravitational flow on terraces. It was recorded that the Shalimar Bagh in Lahore had 450 fountains, and the pressure was so high that water could be thrown 12 feet into the air, falling back down to create a rippling floral effect on the surface of the water.[18]

The Mughals were obsessed with symbol and incorporated it into their gardens in many ways. The standard Quranic references to paradise were in the architecture, layout, and in the choice of plant life; but more secular references, including numerological and zodiacal significances connected to family history or other cultural significance, were often juxtaposed. The numbers eight and nine were considered auspicious by the Mughals and can be found in the number of terraces or in garden architecture such as octagonal pools.[19] Garden flora also had symbolic meanings. The Cypress trees represented eternity and flowering fruit trees represented renewal.[19]

Academic research

editAn early textual references about Mughal gardens are found in the memoirs and biographies of the Mughal emperors, including those of Babur, Humayun and Akbar. Later references are found from "the accounts of India" written by various European travellers (Bernier for example). The first serious historical study of Mughal gardens was written by Constance Villiers-Stuart, with the title Gardens of the Great Mughals (1913).[20] She was consulted by Edwin Lutyens and this may have influenced his choice of Mughal style for the Viceroy's Garden in 1912.

Sites

editAfghanistan

editBangladesh

editIndia

editDelhi

edit- Humayun's Tomb, Nizamuddin East

- Qudsia Bagh

- Amrit Udyan

- Red Fort

- Roshanara Bagh

- Safdarjung's Tomb

- Shalimar Bagh, Delhi

Haryana

editJammu and Kashmir

editKarnataka

editMaharashtra

editPunjab

editRajasthan

edit- Jahangir's Garden at Ajmer

- Lotus Garden at Dholpur

Uttar Pradesh

edit- Agra Fort

- Akbar's Tomb

- Aram Bagh

- Khusro Bagh

- Mehtab Bagh

- Taj Mahal

- Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah

- Tomb of Mariam-uz-Zamani

- Zenana Gardens

Pakistan

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ Penelope Hobhouse; Erica Hunningher; Jerry Harpur (2004). Gardens of Persia. Kales Press. pp. 7–13. ISBN 9780967007663.

- ^ REHMAN, ABDUL (2009). "Changing Concepts of Garden Design in Lahore from Mughal to Contemporary Times". Garden History. 37 (2): 205–217. ISSN 0307-1243. JSTOR 27821596.

- ^ Jellicoe, Susan. "The Development of the Mughal Garden", MacDougall, Elisabeth B.; Ettinghausen, Richard. The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington D.C. (1976). p109

- ^ Hussain, Mahmood; Rehman, Abdul; Wescoat, James L. Jr. The Mughal Garden: Interpretation, Conservation and Implications, Ferozsons Ltd., Lahore (1996). p 207

- ^ Neeru Misra and Tanay Misra, Garden Tomb of Humayun: An Abode in Paradise, Aryan Books International, Delhi, 2003

- ^ Koch, Ebba. "The Char Bagh Conquers the Citadel: an Outline of the Development if the Mughal Palace Garden," Hussain, Mahmood; Rehman, Abdul; Wescoat, James L. Jr. The Mughal Garden: Interpretation, Conservation and Implications, Ferozsons Ltd., Lahore (1996). p. 55

- ^ With his son Shah Jahan. Jellicoe, Susan "The Development of the Mughal Garden" MacDougall, Elisabeth B.; Ettinghausen, Richard. The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington D.C. (1976). p 115

- ^ Moynihan, Elizabeth B. Paradise as Garden in Persia and Mughal India, Scholar Press, London (1982)p 121-123.

- ^ Villiers-Stuart, C. M. (1913). The Gardens of the Great Mughals. Adam and Charles Black, London. p. 53.

- ^ Jellicoe, Susan "The Development of the Mughal Garden" MacDougall, Elisabeth B.; Ettinghausen, Richard. The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington D.C. (1976). p 121

- ^ Tulips are metaphorically considered to be "branded by love" in Persian poetry. Meisami, Julie Scott. "Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (May, 1985), p. 242

- ^ Dar 1982, p. 45

- ^ a b Dickie 1985, p. 136

- ^ "History Of Mughal Gardens".

- ^ Brown, Rebecca (2015). A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119019534. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ Meisami, Julie Scott. "Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez," International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (May, 1985), p. 231; The Old Persian word pairideaza (transliterated to English as paradise) means "walled garden". Moynihan, Elizabeth B. Paradise as Garden in Persia and Mughal India, Scholar Press, London (1982), p. 1.

- ^ Allsen, Thomas T. Commodity and Exchange n the Mongol Empire: A Cultural History of Islamic Textiles, Cambridge University Press (1997). p 12-26

- ^ Fatima, Sadaf (2012). "Waterworks in Mughal Gardens". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 73: 1268–1278. JSTOR 44156328.

- ^ a b Moynihan, Elizabeth B. Paradise as Garden in Persia and Mughal India, Scholar Press, London (1982). p100-101

- ^ Villiers-Stuart, Constance Mary (1913). Gardens of the great Mughals. A. & C. Black.

Sources

edit- Dar, Saifur Rahman (1982). Historical Gardens of Lahore.

- Dickie, James (1985). "The Mughal Garden". In Grabar, Oleg (ed.). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 9004076115.

Further reading

edit- Crowe, Sylvia (2006). The gardens of Mughul India: a history and a guide. Jay Kay Book Shop. ISBN 978-8-187-22109-8.

- Lehrman, Jonas Benzion (1980). Earthly paradise: garden and courtyard in Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04363-4.

- Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2008). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-4025-1.

- Wescoat, James L.; Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (1996). Mughal gardens: sources, places, representations, and prospects. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-884-02235-0.