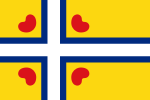

Frisian nationalism (West Frisian: Frysk nasjonalisme, Dutch: Fries nationalisme, German: friesischer Nationalismus) refers to the nationalism which views Frisians as a nation with a shared culture. Frisian nationalism seeks to achieve greater levels of autonomy for Frisian people, and also supports the cultural unity of all Frisians regardless of modern-day territorial borders. The Frisians derive their name from the Frisii, an ancient Germanic tribe which inhabited the northern coastal areas in what today is the northern Netherlands, although historical research has indicated a lack of direct ethnic continuity between the ancient Frisii and later medieval 'Frisians' from whom modern Frisians descend.[1] In the Middle Ages, these Frisians formed the Kingdom of Frisia and later the Frisian freedom confederation, before being subsumed by stronger foreign powers up to this day.

The lands inhabited by Frisians are today known as Frisia and they stretch throughout the Wadden Sea region from the northern Netherlands to north-western Germany. These areas have sometimes been collectively referred to with the Latin names Magna Frisia (Greater Frisia) and Tota Frisia (Whole Frisia).[2] Frisia is usually divided into three parts: West Frisia in the northern Netherlands, East Frisia in the German state of Lower Saxony, and North Frisia in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. Frisia is also divided between different languages, with the only ones remaining today being West Frisian in the Netherlands, by far the most widespread, and the less-spoken Saterland Frisian in Lower Saxony and North Frisian in northwestern Schleswig-Holstein.

Since the end of the Renaissance, these lands have been ruled by foreign powers and Frisian culture has gradually been supplanted in many areas by those of their administrators, with Frisian nationalism arising as a conscious movement primarily in the 19th century.[3] In the 19th and 20th centuries, increasing contacts between Dutch and German Frisians spurred the formation of a transnational consciousness which was typified by conceptions of a shared history, an occasionally ambivalent or even absent relationship with the Frisian language (which had been supplanted by Dutch and German in many areas), an emphasis on peripheral rurality, and a view of Frisians as having a "loving, independent and level-headed" character.[2] However, despite the romanto-mythical notions of early Frisian nationalists who often wrote of a Great Frisian Empire of the past and modern Frisia's historical continuity with it, modern-day historical research has indicated that Frisia has long had a complex sociopolitical landscape and that modern Frisia's relationship to its past contains some elements which are "discontinuous, ambivalent and even contrary."[2]

History

editAntecedents

editThere have been occasional early expressions of Frisian nationalism. One scholar, speaking of Frisian resistance to the Franks, wrote that "for over sixty years Frisian nationalism and heathenism also went hand in hand, as heathenism proved an indispensable ideological component of the resistance to Frankish imperialism."[4] The 16th century in particular represented an early peak.[5][6] In that century, it was popular among West Frisians to attach Frisius to one's surname, and the historian Suffridius Petrus (1527–1597) composed an anthology of Frisian writers entitled De scriptoribus Frisiae (On Frisian Writers). In addition, Petrus was also an early advocate of the "Magna Frisia" (Greater Frisia) concept.[5] Petrus had even claimed that Prester John was a Frisian prince named John Adgill.[6] The North Frisian chronicler Peter Sax wrote in 1636 that the Frisians had "a common language...so they are also all one people with each other."[7] Sax set out to collect knowledge and historical maps about North Frisia and published his research in 1638 as a parchment volume.[8]

Dutch Frisia

editThe origins of modern Frisian nationalism lay primarily in the 19th century,[3][9] which was well after the region of Frisia entered a state of political, cultural, and economic decline after centuries of relative prosperity. Frisia had been a confederation in the Middle Ages with territory slightly greater than that which it encompasses today. However, Dutch replaced Frisian first as the administrative language in 1498, and later as the cultural lingua franca after Frisia was incorporated in 1579 into the Union of Utrecht. Dutch soon become the language not only of administration but also the Frisian Church, rendering Frisian virtually obsolete in the public sphere. In addition, a Dutch-Frisian mixed language known as stadsfries ("town Frisian") arose, further complicating Frisian cultural expression.[3] Nonetheless, the region of Frisia continued to prosper with a highly commercialised economy, strong literacy rates, and a robust economy of luxury goods. At this time, moreover, Frisia maintained relatively decent levels of administrative autonomy. In the latter half of the 18th century, however, the Netherlands increasingly began to assert its own nationalism and centralised governance to the detriment of Frisian autonomy. Frisia's former prosperity declined, especially following an agricultural crisis in 1878 which saw many emigrate to the United States. Frisia gradually became a relatively quiet and rural land on the periphery of Dutch life, and remains so today.[3]

Earlier appeals to Frisian liberty were primarily political rather than cultural in character and could be traced back to an alleged exemption from feudalism granted to the Frisians by Charlemagne. In the High Middle Ages, Frisians, who then formed a free confederation, used this alleged history for political purposes by legitimising armed resistance to domination, as was seen in the Battle of Warns.[2] In the 19th century, however, after Frisia had been subsumed into the Sovereign Principality of the United Netherlands, Frisians compensated for their loss of political autonomy with a new-found cultural nationalism.[2] As with many other nationalisms, the Frisian nationalist project required turning an array of indistinct ethnic communities speaking differing variants of the Frisian language, German and/or Dutch into a single self-aware nation of "Frisians." In the Netherlands, where West Frisian remains by far the most widely spoken Frisian language, these nationalists also placed heavy emphasis on language as the "soul of the nation",[2] and its preservation has come to define the movement of autonomy.[9] Frisian intellectuals increasingly began to write in the language after it had formerly been purely a spoken language.[10] In general, a large number of societies formed in the 19th and early 20th centuries to promote Frisian cultural interests.[3]

Historiography has also played a key role, particularly in earlier times, as it was in the medieval past that an example of a free Frisian polity could be found. As one author put it, the Frisian nation "existed only in so far as [its history, literature, and language] was talked about." This thirst for historical study was satisfied in part through publications such as the Frisian People's Almanac (Friesche Volksalmanak) which was primarily devoted to historiographic writings. Around 1880, this almanac took on a more chauvinist tone and stressed the need for "purity" of the Frisian people and viewed the Frisians as having retained early Germanic culture and customs in its purest form, whereas the Dutch have corrupted it.[11] Another popular symbol of Frisian nationalism since the beginning of the 20th century has been the Friesian horse,[9][12] and regional breeders began to stress the need for Friesian purebreds over reliance on foreign horse breeds.[12]

German Frisia

editNorth Frisia

editModern-day Germany is home to two of the three segments of Frisia as typically defined by proponents. One of these is North Frisia, which is located in a western coastal portion of the state of Schleswig-Holstein today. Despite its name, Low German became more popularly spoken than North Frisian by the 1600s.[11] Nonetheless, this region was historically diverse and, by the 19th century, was shared between Germans, Danes, and North Frisians primarily. In the context of 19th century nationalism, the region was the subject of the so-called Schleswig-Holstein Question, and although it was mainly a dispute between Germany and Denmark, North Frisians were also caught in the socio-political crossfire.[11] As it turns out, teachers in Frisian-speaking areas seem not to have had an intense drive to preserve the language as was seen in Dutch Frisia, and instead viewed teaching Frisian as an obstacle to potential societal advancement for children in a nationalist Europe that was increasingly taking on a "one nation, one language" mentality.[13]

One notable individual who supported some semblance of Frisian identity was Cornelius Petersen (1882–1935), a farmer who grew up speaking Low German but later learned both Frisian and Danish in addition to agitating for greater autonomy in Schleswig. In his pamphlet Die friesische Bewegung (The Frisian Movement), he took up a Frisian identity and argued that a model should be sought in the "yeoman republicanism of Frisians, Dithmarshers, and medieval Saxons" rather than the centralising expansionism of Franks, Prussians, or Danes.[11] Petersen argued that Frisians had lost their national pride by excessively adopting foreign traditions and being taught by their invaders to look down upon their own as "provincial" and "anachronistic." Nonetheless, in his vision, Frisian was not used as an ethno-linguistic category to justify state nationalism, but rather a symbol for the "peasant tradition" of southwestern Jutland, contrasting "organic local community" with state bureaucracy and thus arguing for pre-modern localism and regionalism. As a result, this idiosyncratic anti-nationalism failed to garner a widespread following.[11]

East Frisia

editIn modern times, Saterland Frisian is the only remaining dialect of the East Frisian language, and is spoken primarily in the area of Saterland in Lower Saxony. As with the West Frisians, it has been said that Saterlanders have used their Frisian origin in the past so as to protect privileges they believed granted to them through the Frisian freedom; in one instance they are said to have countered the Bishop of Münster in this regard.[14] And yet, 19th century travel accounts by West Frisian nationalists to Saterland showed that the inhabitants there referred to themselves only as Saterlanders and not Frisians. Two studies by two different German researchers in the late 19th century produced studies of the Saterlanders and both argued that their Frisian origin could be indisputably determined by linguistic study as well as by observing their customs and manners. Despite all of this, they did not describe any self-awareness on the part of the Saterlanders of being "Frisian" and one of the researchers even said that some of the Saterland inhabitants claimed descent from the Chauci tribe.[14] As a result, it can be said that Frisian national feeling was low among the Saterlanders in the 19th century.

Modern day

editFrisians are recognised as a distinct national minority in Germany,[15] but not the Netherlands.[16][better source needed] In the Dutch province of Friesland, the West Frisian language is spoken by around 74% and understood by around 94% of the inhabitants. Moreover, it is mandatory for provincial children to learn the language.[9] Overall, the West Frisian language has around 470,000 speakers as of 2001,[17] and is recognised as a regional language in the Netherlands.[16][better source needed] The Frisian language continuum has fared far worse in German Frisia where they form a minority of the worldwide native speakers of Frisian languages,[18] although exact numbers vary relatively widely.

Despite the modern survival of the West Frisian language in Friesland, use of Frisian in church services has remained controversial as late as the 1980s, and approval from local consistories has been needed to utilise the language in hymns and sermons.[19]

In modern times, Frisian nationalism has, as with other nationalisms, been expressed through tourism and the commodification of tangible cultural heritage. Friesland provincial planners have promoted "typical Frisian sporting event[s]" such as cargo ship regattas and pole jumping and bolstered these with Frisian flags and 'signal' words.[2]

Political groups

editTransnational

editThe Interfrisian Council was founded in 1956 in order to represent the interests of all regions of Frisia across both Germany and the Netherlands.

Netherlands

editThe Frisian National Party was founded in 1962 and supports greater regional autonomy for Frisians in the Netherlands.

Groep fan Auwerk, on the other hand, goes one step further in advocating for an independent Frisian nation-state.

Germany

editThe South Schleswig Voters' Association was founded in 1948 and advocates for both the Frisian and Danish minorities of the state of Schleswig-Holstein in Germany.

Die Friesen was founded much later, in 2007, and advocates for the self-determination of Germany's Frisian minority.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Bazelmans, Jos (2009). "The early-medieval use of ethnic names from classical antiquity: The case of the Frisians". In Derks, Ton; Roymans, Nico (eds.). Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition. Ton Derks, Nico Roymans. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. pp. 321–337. ISBN 978-90-485-0791-7. OCLC 391593170.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jensma, Goffe (2018). "Remystifying Frisia". In Egberts, Linde; Schroor, Meindert (eds.). Remystifying Frisia: The 'experience economy' along the Wadden Sea coast. History, Landscape and Cultural Heritage of the Wadden Sea Region. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 151–168. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7xbrmk.13. ISBN 978-94-6298-660-2. JSTOR j.ctv7xbrmk.13. S2CID 240224713.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Boucher, Harrison (2017). "Ethnolinguistic Nationalism in Fryslân". Gustavus Adolphus College. Archived from the original on 2021-11-10. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ Clogan, Paul Maurice (1995). Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Culture: Diversity. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 6. ISBN 0-8476-8099-1. OCLC 34050915.

- ^ a b Vanderjagt, Arie Johan; Akkerman, Fokke (1988). Rodolphus Agricola Phrisius, 1444-1485: Proceedings of the International Conference at the University of Groningen, 28-30 October 1985. Leiden: BRILL. p. 178. ISBN 90-04-08599-8. OCLC 17354182.

- ^ a b Brewer, Keagan (2019). Prester John: The Legend and its Sources. Keagan Brewer (1st ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-315-60209-7. OCLC 1112671788.

- ^ Munske, Horst Haider; Århammar, Nils; Vries, Oebele; Faltings, Volker F.; Hoekstra, Jarich F.; Walker, Alastair G. H.; Wilts, Ommo (2001). Handbuch des Friesischen (Handbook of Frisian studies). Tübingen: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. p. 698. ISBN 3-484-73048-X. OCLC 53814304.

- ^ Ehrensvärd, Ulla (2006). The History of the Nordic Map: From Myths to Reality. Antoine Lafréry, John Nurmisen säätiö. Helsinki: John Nurminen Foundation. p. 174. ISBN 952-9745-20-6. OCLC 266230484.

- ^ a b c d Hannan, Martin (2017). "Wha's Like Us: The independence movements of the Netherlands & Poland". The National.

- ^ Halink, Simon (2019). Northern Myths, Modern Identities: The Nationalisation of Northern Mythologies Since 1800. BRILL. p. 105. ISBN 9789004398436.

- ^ a b c d e Thaler, Peter (2008). "Identity on a Personal Level: Sleswig Biographies during the Age of Nationalism". Scandinavian Studies. 80 (1): 51–84. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40920788.

- ^ a b Guest, Kristen; Mattfeld, Monica (2019). Horse Breeds and Human Society: Purity, Identity and the Making of the Modern Horse. Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-02400-9. OCLC 1128890345.

- ^ Russi, Cinzia (2016). Current Trends in Historical Sociolinguistics. Basel/Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. p. 105. ISBN 978-3-11-048840-1. OCLC 964453412.

- ^ a b Fellerer, Jan; Turda, Marius; Pyrah, Robert, eds. (2019). Identities In-Between in East-Central Europe. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-28261-4. OCLC 1112671727.

- ^ "National minorities". Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community.

- ^ a b Muscato, Christopher. "Ethnic Groups in the Netherlands". Study.com.

- ^ West Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ^ Burnett, M. Troy (2020). Nationalism Today: Extreme Political Movements Around the World. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-4408-5000-4. OCLC 1137735471.

- ^ Spolsky, Bernard (2004). Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-107-32138-0. OCLC 829706614.