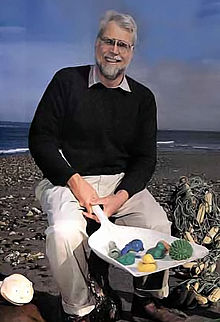

Friendly Floatees are plastic bath toys (including rubber ducks) marketed by The First Years and made famous by the work of Curtis Ebbesmeyer, an oceanographer who models ocean currents on the basis of flotsam movements. Ebbesmeyer studied the movements of a consignment of 28,800 Friendly Floatees—yellow ducks, red beavers, blue turtles, and green frogs—that were washed into the Pacific Ocean in 1992. Some of the toys landed along Pacific Ocean shores, such as Hawaii. Others traveled over 27,000 kilometres (17,000 mi), floating over the site where the Titanic sank, and spent years frozen in Arctic ice before reaching the U.S. Eastern Seaboard as well as British and Irish shores, fifteen years later, in 2007.[citation needed]

Oceanography

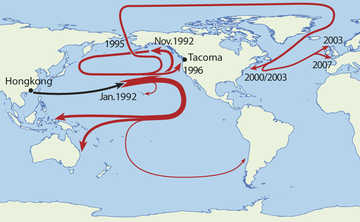

editA consignment of Friendly Floatee toys, manufactured in China for The First Years Inc., departed from Hong Kong on a container ship, the Evergreen Ever Laurel,[1] destined for Tacoma, Washington. On 10 January 1992, during a storm in the North Pacific Ocean close to the International Date Line, twelve 40-foot (12-m) intermodal containers were washed overboard. One of these containers held 28,800 Floatees,[2][3] a child's bath toy which came in a number of forms: red beavers, green frogs, blue turtles and yellow ducks. At some point, the container opened (possibly because it collided with other containers or the ship itself) and the Floatees were released. Although each toy was mounted in a cardboard housing attached to a backing card, subsequent tests showed that the cardboard quickly degraded in sea water allowing the Floatees to escape. Unlike many bath toys, Friendly Floatees have no holes in them so they do not take on water.

Seattle oceanographers Curtis Ebbesmeyer and James Ingraham, who were working on an ocean surface current model, began to track their progress. The mass release of 28,800 objects into the ocean at one time offered significant advantages over the standard method of releasing 500–1000 drift bottles. The recovery rate of objects from the Pacific Ocean is typically around 2%, so rather than the 10 to 20 recoveries typically seen with a drift bottle release, the two scientists expected numbers closer to 600. They were already tracking various other spills of flotsam, including 61,000 Nike running shoes that had been lost overboard in 1990.

Ten months after the incident, the first Floatees began to wash up along the Alaskan coast. The first discovery consisted of ten toys found by a beachcomber near Sitka, Alaska on 16 November 1992, about 3,200 kilometres (2,000 mi) from their starting point. Ebbesmeyer and Ingraham contacted beachcombers, coastal workers, and local residents to locate hundreds of the beached Floatees over a 850 kilometres (530 mi) shoreline. Another beachcomber discovered twenty of the toys on 28 November 1992, and in total 400 were found along the eastern coast of the Gulf of Alaska in the period up to August 1993. This represented a 1.4% recovery rate. The landfalls were logged in Ingraham's computer model OSCUR (Ocean Surface Currents Simulation), which uses measurements of air pressure from 1967 onwards to calculate the direction of and speed of wind across the oceans, and the consequent surface currents. Ingraham's model was built to help fisheries but it is also used to predict flotsam movements or the likely locations of those lost at sea.

Using the models they had developed, the oceanographers correctly predicted further landfalls of the toys in Washington state in 1996 and theorized that many of the remaining Floatees would have traveled to Alaska, westward to Japan, back to Alaska, and then drifted northwards through the Bering Strait and become trapped in the Arctic pack ice. Moving slowly with the ice across the Pole, they predicted it would take five or six years for the toys to reach the North Atlantic where the ice would thaw and release them. Between July and December 2003, The First Years Inc. offered a $100 US savings bond reward to anybody who recovered a Floatee in New England, Canada or Iceland.

More of the toys were recovered in 2004 than in any of the preceding three years. However, still, more of these toys were predicted to have headed eastward past Greenland and make landfall on the southwestern shores of the United Kingdom in 2007. In July 2007, a retired teacher found a plastic duck on the Devon coast, and British newspapers mistakenly announced that the Floatees had begun to arrive.[4] But the day after breaking the story, the Western Morning News, the local Devon newspaper, reported that Dr. Simon Boxall of the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton had examined the toy and determined that the duck was not in fact a Floatee.[5]

Bleached by sun and seawater, the ducks and beavers had faded to white, but the turtles and frogs had kept their original colors.

Legacy

editAt least two children's books have been inspired by the Floatees. In 1997, Clarion Books published Ducky (ISBN 0-395-75185-3), written by Eve Bunting and illustrated by Caldecott Medal winner David Wisniewski. Hans Christian Andersen Award winner Eric Carle wrote 10 Little Rubber Ducks (Harper Collins 2005, ISBN 978-0-00-720242-3).[6]

In 1997 Black Swan published That Awkward Age (Transworld 1997, ISBN 978-0552996716), a comedy written by Mary Selby, in which several of the ducks are found off the Isle of Lewis, one then being purchased at auction and treated as a metaphor for perseverance.

In 2003, Rich Eilbert wrote a song "Yellow Rubber Ducks" commemorating the ducks' journey. In 2011, he published the song as a YouTube video, Yellow Rubber Ducks.

In 2011, Donovan Hohn published Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them (Viking, ISBN 978-0-670-02219-9)[7]

On the 19th of February 2013, BBC mystery series Death in Paradise featured the spill as a plot point in the 7th episode of Series 2.[8]

On 20 June 2014, The Disney Channel and Disney Junior aired Lucky Duck, a Canadian-American animated TV movie that is loosely based on and inspired by the Friendly Floatees.[9]

In his 2014 poem collection The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion, poet Kei Miller dedicates a poem to the Friendly Floatees : "When Considering the Long, Long Journey of 28,000 Rubber Ducks".

The spill was referenced in a 2022 game "Placid Plastic Duck Simulator" as an "accidental duck experiment", which can be heard on the radio in between music.

The toys themselves have become collector's items, fetching prices as high as $1,000.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Hohn, Donovan (March 2011). The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them. Viking. ISBN 9780670022199.

- ^ "What connects the 'Ever Given', the Suez Canal and 7,200 rubber ducks loose in the Pacific?". The National. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Hohn, Donovan (January 2007). "Moby-Duck: Or, The Synthetic Wilderness of Childhood". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "First of the plastic duck invasion fleet makes landfall on the Devon coast". The Times. London. 14 July 2000.[dead link]

- ^ "Expert rules out toy duck as lost ocean adventurer". Western Morning News. 14 July 2007.

- ^ Wilkinson, Carl (17 February 2012). "Ugly Ducklings". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ^ "Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea by Donovan Hohn". The Guardian. 30 March 2012.

- ^ O'Neill, David (19 February 2013), A Deadly Storm, Death in Paradise, Stephen Boxer, Gemma Chan, Jo Woodcock, retrieved 23 November 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Lucky Duck". Disney Junior. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

References

edit- Hohn, Donovan, Moby-Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them. Viking, New York, NY 2011, ISBN 978-0-670-02219-9

- Curtis C. Ebbesmeyer and W. James Ingraham Jr. (October 1994). "Pacific Toy Spill Fuels Ocean Current Pathways Research". Earth in Space. 7 (2): 7–9, 14. Bibcode:1994EOSTr..75..425E. doi:10.1029/94EO01056. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- "Ducks embark on a scientific journey". The First Years Inc. 2003. Archived from the original on 1 October 2003. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- "Rubber Duckies Map The World". CBS News. 31 July 2003. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- Ed Perry, Ed. (May 2005). "The Drifting Seed newsletter" (PDF). Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- Curtis C. Ebbesmeyer. "Beachcombing Science from Bath Toys". Archived from the original on 10 November 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- Simon de Bruxelles (28 June 2007). "Plastic duck armada is heading for Britain after 15-year global voyage". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- "The popular television show "Touch" based season 1 episode 11, "The Gyre, Pt. 1" on the floating duck phenomenon, citing the maritime accident that released the ducks into the sea". Imdb.com. 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

External links

edit- Keith C. Heidorn, 'Of Shoes And Ships And Rubber Ducks And A Message In A Bottle', The Weather Doctor (17 March 1999).

- Jane Standley, 'Ducks' odyssey nears end', BBC News, (12 July 2003).

- Duck ahoy, The Age, (7 August 2003)

- Marsha Walton, 'How Nikes, toys and hockey gear help ocean science', CNN.com (26 May 2003).

- "Journey of the Floatees", Spiegel magazine (1 July 2007)

- "Timeline of Rubber Duck Voyage", Rubaduck.com

- Donovan Hohn, "Moby-Duck: Or, The Synthetic Wilderness of Childhood," Harper's Magazine, January (2007), pp. 39–62.

- Moby Duck: The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, Including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them Archived 7 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine – follow up non-fiction book based on 2 years research after the Harper's Magazine article.

- Rich Eilbert, Yellow Rubber Ducks, YouTube.com, (March 2011).