This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (November 2017) |

|

French |

| Authors • Lit categories |

|

French literary history Medieval |

|

Literature by country |

|

Portals |

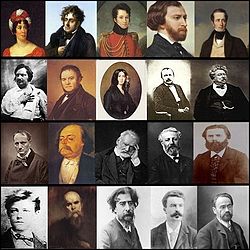

19th-century French literature concerns the developments in French literature during a dynamic period in French history that saw the rise of Democracy and the fitful end of Monarchy and Empire. The period covered spans the following political regimes: Napoleon Bonaparte's Consulate (1799–1804) and Empire (1804–1814), the Restoration under Louis XVIII and Charles X (1814–1830), the July Monarchy under Louis Philippe d'Orléans (1830–1848), the Second Republic (1848–1852), the Second Empire under Napoleon III (1852–1871), and the first decades of the Third Republic (1871–1940).

Overview

editFrench literature enjoyed enormous international prestige and success in the 19th century. The first part of the century was dominated by Romanticism, until around the mid-century Realism emerged, at least partly as a reaction. In the last half of the century, "naturalism", "parnassian" poetry, and "symbolism", among other styles, were often competing tendencies at the same time. Some writers did form into literary groups defined by a name and a program or manifesto. In other cases, these expressions were merely pejorative terms given by critics to certain writers or have been used by modern literary historians to group writers of divergent projects or methods. Nevertheless, these labels can be useful in describing broad historical developments in the arts.

Romanticism

editFrench literature from the first half of the century was dominated by Romanticism, which is associated with such authors as Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, père, François-René de Chateaubriand, Alphonse de Lamartine, Gérard de Nerval, Charles Nodier, Alfred de Musset, Théophile Gautier and Alfred de Vigny. Their influence was felt in theatre, poetry, prose fiction. The effect of the romantic movement would continue to be felt in the latter half of the century in diverse literary developments, such as "realism", "symbolism", and the so-called fin de siècle "decadent" movement.

French romanticism used forms such as the historical novel, the romance, the "roman noir" or Gothic novel; subjects like traditional myths (including the myth of the romantic hero), nationalism, the natural world (i.e. elegies by lakes), and the common man; and the styles of lyricism, sentimentalism, exoticism and orientalism. Foreign influences played a big part in this, especially those of Shakespeare, Walter Scott, Byron, Goethe, and Friedrich Schiller. French Romanticism had ideals diametrically opposed to French classicism and the classical unities, but it could also express a profound loss for aspects of the pre-revolutionary world in a society now dominated by money and fame, rather than honor.

Key ideas from early French Romanticism:[citation needed]

- "Le vague des passions" (vagueness, uncertainty of sentiment and passion): Chateaubriand maintained that while the imagination was rich, the world was cold and empty, and civilization had only robbed men of their illusions; nevertheless, a notion of sentiment and passion continued to haunt men.

- "Le mal du siècle" (the pain of the century): a sense of loss, disillusion, and aporia, typified by melancholy and lassitude.

Romanticism in England and Germany largely predate French romanticism, although there was a kind of "pre-romanticism" in the works of Senancour and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (among others) at the end of the 18th century. French Romanticism took definite form in the works of François-René de Chateaubriand and Benjamin Constant and in Madame de Staël's interpretation of Germany as the land of romantic ideals. It found early expression also in the sentimental poetry of Alphonse de Lamartine.

The major battles of romanticism in France were in the theater. The early years of the century were marked by a revival of classicism and classical-inspired tragedies, often with themes of national sacrifice or patriotic heroism in keeping with the spirit of the Revolution, but the production of Victor Hugo's Hernani in 1830 marked the triumph of the romantic movement on the stage (a description of the turbulent opening night can be found in Théophile Gautier). The dramatic unities of time and place were abolished, tragic and comic elements appeared together and metrical freedom was won. Marked by the plays of Friedrich Schiller, the romantics often chose subjects from historic periods (the French Renaissance, the reign of Louis XIII of France) and doomed noble characters (rebel princes and outlaws) or misunderstood artists (Vigny's play based on the life of Thomas Chatterton).

Victor Hugo was the outstanding genius of the Romantic School and its recognized leader. He was prolific alike in poetry, drama, and fiction. Other writers associated with the movement were the austere and pessimistic Alfred de Vigny, Théophile Gautier a devotee of beauty and creator of the "Art for art's sake" movement, and Alfred de Musset, who best exemplifies romantic melancholy. All three also wrote novels and short stories, and Musset won a belated success with his plays. Alexandre Dumas, père wrote The Three Musketeers and other romantic novels in an historical setting. Prosper Mérimée and Charles Nodier were masters of shorter fiction. Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, a literary critic, showed romantic expansiveness in his hospitality to all ideas and in his unfailing endeavour to understand and interpret authors rather than to judge them.

Romanticism is associated with a number of literary salons and groups: the Arsenal (formed around Charles Nodier at the Arsenal Library in Paris from 1824-1844 where Nodier was administrator), the Cénacle (formed around Nodier, then Hugo from 1823–1828), the salon of Louis Charles Delescluze, the salon of Antoine (or Antony Deschamps), the salon of Madame de Staël.

Romanticism in France defied political affiliation: one finds both "liberal" (like Stendhal), "conservative" (like Chateaubriand) and socialist (George Sand) strains.

Realism

editThe expression "Realism", when being applied to literature of the 19th century, implies the attempt to depict contemporary life and society. The growth of realism is linked to the development of science (especially biology), history and the social sciences and to the growth of industrialism and commerce. The "realist" tendency is not necessarily anti-romantic; romanticism in France often affirmed the common man and the natural setting, as in the peasant stories of George Sand, and concerned itself with historical forces and periods, as in the work of historian Jules Michelet.

The novels of Stendhal, including The Red and the Black and The Charterhouse of Parma, address issues of their contemporary society while also using themes and characters derived from the romantic movement. Honoré de Balzac is the most prominent representative of 19th century realism in fiction. His La Comédie humaine, a vast collection of nearly 100 novels, was the most ambitious scheme ever devised by a writer of fiction—nothing less than a complete contemporary history of his countrymen. Realism also appears in the works of Alexandre Dumas, fils.

Many of the novels in this period, including Balzac's, were published in newspapers in serial form, and the immensely popular realist "roman feuilleton" tended to specialize in portraying the hidden side of urban life (crime, police spies, criminal slang), as in the novels of Eugène Sue. Similar tendencies appeared in the theatrical melodramas of the period and, in an even more lurid and gruesome light, in the Grand Guignol at the end of the century.

Gustave Flaubert's great novels Madame Bovary (1857)—which reveals the tragic consequences of romanticism on the wife of a provincial doctor—and Sentimental Education represent perhaps the highest stages in the development of French realism, while Flaubert's romanticism is apparent in his fantastic The Temptation of Saint Anthony and the baroque and exotic scenes of ancient Carthage in Salammbô.

In addition to melodramas, popular and bourgeois theater in the mid-century turned to realism in the "well-made" bourgeois farces of Eugène Marin Labiche and the moral dramas of Émile Augier.

Naturalism

editFrom the 1860s on, critics increasingly speak of literary "Naturalism". The expression is imprecise, and was frequently used disparagingly to characterize authors whose chosen subject matter was taken from the working classes and who portrayed the misery and harsh conditions of real life. Many of the "naturalist" writers took a radical position against the excesses of romanticism and strove to use scientific and encyclopedic precision in their novels (Zola spent months visiting coal mines for his Germinal, and even the arch-realist Flaubert was famous for his years of research for historical details). Hippolyte Taine supplied much of the philosophy of naturalism: he believed that every human being was determined by the forces of heredity and environment and by the time in which he lived. The influence of certain Norwegian, Swedish and Russian writers gave an added impulse to the naturalistic movement.

The novels and short stories of Guy de Maupassant are often tagged with the label "naturalist", although he clearly followed the realist model of his teacher and mentor, Flaubert. Maupassant used elements derived from the gothic novel in stories like Le Horla. This tension between portrayal of the contemporary world in all its sordidness, detached irony and the use of romantic images and themes would also influence the symbolists (see below) and would continue to the 20th century.

Naturalism is most often associated with the novels of Émile Zola in particular his Les Rougon-Macquart novel cycle, which includes Germinal, L'Assommoir, Nana, Le Ventre de Paris, La Bête humaine, and L'Œuvre (The Masterpiece), in which the social success or failure of two branches of a family is explained by physical, social and hereditary laws. Other writers who have been labeled naturalists include: Alphonse Daudet, Jules Vallès, Joris-Karl Huysmans (later a leading "decadent" and rebel against naturalism),[1] Edmond de Goncourt and his brother Jules de Goncourt, and (in a very different vein) Paul Bourget.

Parnasse

editAn attempt to be objective[clarification needed] was made in poetry by the group of writers known as the Parnassians—which included Leconte de Lisle, Théodore de Banville, Catulle Mendès, Sully-Prudhomme, François Coppée, José María de Heredia and (early in his career) Paul Verlaine—who (using Théophile Gautier's notion of art for art's sake and the pursuit of the beautiful) strove for exact and faultless workmanship, and selected exotic and classical subjects which they treated with a rigidity of form and an emotional detachment (elements of which echo the philosophical work of Arthur Schopenhauer whose aesthetic theories would also have an influence on the symbolists).

Modern science and geography were united with romantic adventure in the works of Jules Verne and other writers of popular serial adventure novels and early science-fiction.

Symbolism and the birth of the Modern

editThe naturalist tendency to see life without illusions and to dwell on its more depressing and sordid aspects appears in an intensified degree in the immensely influential poetry of Charles Baudelaire, but with profoundly romantic elements derived from the Byronic myth of the anti-hero and the romantic poet, and the world-weariness of the "mal du siècle", etc. Similar elements occur in the novels of Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly.

The poetry of Baudelaire and much of the literature in the latter half of the century (or "fin de siècle") were often characterized as "decadent" for their lurid content or moral vision. In a similar vein, Paul Verlaine used the expression "poète maudit" ("accursed poet") in 1884 to refer to a number of poets like Tristan Corbière, Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud who had fought against poetic conventions and suffered social rebuke or had been ignored by the critics. But with the publication of Jean Moréas Symbolist Manifesto in 1886, it was the term symbolism which was most often applied to the new literary environment.

The writers Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, Paul Valéry, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Arthur Rimbaud, Jules Laforgue, Jean Moréas, Gustave Kahn, Albert Samain, Jean Lorrain, Rémy de Gourmont, Pierre Louÿs, Tristan Corbière, Henri de Régnier, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam, Stuart Merrill, René Ghil, Saint-Pol-Roux, Oscar-Vladislas de Milosz, Albert Giraud, Emile Verhaeren, Georges Rodenbach and Maurice Maeterlinck and others have been called symbolists, although each author's personal literary project was unique.

The symbolists often share themes that parallel Schopenhauer's aesthetics and notions of will, fatality and unconscious forces. The symbolists often used themes of sex (often through the figure of the prostitute), the city, irrational phenomena (delirium, dreams, narcotics, alcohol), and sometimes a vaguely medieval setting. The tone of symbolism is highly variable, at times realistic, imaginative, ironic or detached, although on the whole the symbolists did not stress moral or ethical ideas. In poetry, the symbolist procedure—as typified by Paul Verlaine—was to use subtle suggestion instead of precise statement (rhetoric was banned) and to evoke moods and feelings by the magic of words and repeated sounds and the cadence of verse (musicality) and metrical innovation. Some symbolists explored the use of free verse. The use of leitmotifs, medieval settings and the notion of the complete work of art (blending music, visuals and language) in the works of the German composer Richard Wagner also had a profound impact on these writers.

Stéphane Mallarmé's profound interest in the limits of language as an attempt at describing the world, and his use of convoluted syntax, and in his last major poem Un coup de dés, the spacing, size and position of words on the page were important modern breakthroughs that continue to preoccupy contemporary poetry in France.

Arthur Rimbaud's prose poem collection Illuminations are among the first free verse poems in French; his biographically inspired poem Une saison en enfer (A Season in Hell) was championed by the Surrealists as a revolutionary modern literary act (the same work would play an important role in the New York City punk scene in the 1970s). The infernal images of the prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror by Isidore Ducasse, Comte de Lautréamont would have a similar impact.

The crisis of language and meaning in Mallarmé and the radical vision of literature, life and the political world in Rimbaud are to some degree the cornerstones of the "modern" and the radical experiments of Dada, Surrealism and Theatre of the Absurd (to name a few) in the 20th century.[citation needed]

See also

editNotes and references

edit- ^ Read Bernard Bonnejean "Huysmans avant À Rebours : les fondements nécessaires d'une quête en devenir", in Le Mal dans l'imaginaire français (1850–1950), éd. David et L'Harmattan, 1998 (ISBN 2-7384-6198-0) ; "Huysmans before A Rebours: The necessary foundation for a quest to become", The evil in the French imaginary (1850–1950), Ed. David and L'Harmattan, 1998 (ISBN 2-7384-6198-0)