The Taita falcon (Falco fasciinucha) is a small falcon found in central and eastern Africa. It was first described from the Taita Hills of Kenya from which it derives its name.

| Taita falcon | |

|---|---|

| |

| photographed at Chimanimani National Park, Zimbabwe | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes |

| Family: | Falconidae |

| Genus: | Falco |

| Species: | F. fasciinucha

|

| Binomial name | |

| Falco fasciinucha | |

Description

editThe Taita falcon is a small, rare raptor species. The biology and ecology of this falcon is not well-understood. It is robust, long winged with a short tail, and is adept at aerial hunting. This falcon bears some resemblance to the African hobby, with which it is often confused; however, the white throat and rufous patches on the nape offer a unique characteristic for identification. The wingspan of the males is 202 to 208 mm (8.0 to 8.2 in), and that of females is 229 to 240 mm (9.0 to 9.4 in). Males weigh 212 to 233 g (7.5 to 8.2 oz) and the females 297 to 346 g (10.5 to 12.2 oz). The plumage of the males is more brightly coloured than the females.[2]

Abundance, Distribution and Habitat

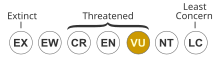

editThe Taita falcon is globally listed as Vulnerable (VU).[1] This species is predicted to be represented by less than 1500 individuals of 500 breeding pairs in its distribution range and only 50 nest sites are known. However, because of their cryptic nature and occupancy of rather remote or inaccessible areas, it is difficult to achieve an accurate assessment of this falcon’s true conservation status. There may also be drastic fluctuations in populations, where breeding pairs decrease unevenly through the landscape.[3]

The Taita falcon has a wide – yet fragmented distribution – from northern South Africa by the Mpumalanga/Limpopo Escarpment, up to Southern Ethiopia, which caps the northern extremity of this falcon’s distribution in Africa.[3] Recently, a pair was observed near the JG Strijdom Tunnel in the Limpopo Province of South Africa.[4] These typically cliff-dwelling falcons are closely associated with highlands and mountainous terrain, in areas of low rainfall. Small, isolated localities support a few breeding pairs where the habitat is suitable.[3] These falcons seem to prefer closed, unfragmented woodlands.[5]

Breeding and Nesting Behaviour

editBreeding success is temporally and spatially variable (Jenkins et al, 2019). The Taita falcon typically nests in cliff holes, protected from direct sunlight (Hartley et al, 1993). Some falcons in Malawi and Zambia have also been found nesting on small granite inselbergs. In the Zimbabwean falcon populations, breeding is predicted to start after July and end around October.[3] Incubation of the eggs is predicted to occur from late August to early September. However, there seems to be variation in breeding season among populations in different locations, where East African pairs are seen to start breeding around April to September. The nest is situated on bare rock and the clutch size is two to four eggs. The incubation period is 31–33 days, and the chicks fledge after approximately 42 days. Taita Falcons are very secretive about the positions of the nests and will readily – and viciously – attack other animals that pose as a threat, such as trumpeter hornbills.[2] The breeding success of the Taita falcon is not well-understood.

Hunting Behaviour and Diet

editThe Taita falcon is a small, fast-flying raptor that catches its prey in the air.[3] This falcon is active mostly from dawn till mid-morning and then again in the mid to late afternoon.[2] It has very small wings relative to its robust build; therefore, this falcon can reach high speeds for hunting.[3] However, owing to its build, flapping flight is costly.[citation needed]

Cliffs are predicted to be a suitable habitat for this species. They provide protection of their eggs because of their inaccessibility, Taita falcons can utilize the orographic lift that is associated with cliffs to reduce flight costs, and they provide naturally good vantage points for hunting prey.[citation needed]

Taita falcons are typically hunting small birds mostly caught in habitats close to the nest, such as red-billed queleas, swifts, hirundines and green-spotted doves. These falcons have been observed to use several different hunting methods, such as speculative hunting – quartering from a cliff top – and stooping from high position to directly pursue prey. They have even been observed as cooperative hunters in Zimbabwe.[2]

Threats to Conservation

editThe Batoka Gorge along the Zambezi River by Victoria Falls was historically the core for Taita falcon distribution, where six breeding pairs were identified during surveys in the 1990’s.[2][3] However, this habitat patch no longer supports these breeding pairs. These population reductions are particularly problematic because of the lack of biological and ecological information on these raptors. Therefore, one can only speculate the factors playing a role in these declines of the Taita falcon in Africa.[citation needed]

Tourism and increased air traffic is predicted to be a significant disturbance to raptors along the Batoka Gorge.[3] Further, the decrease in the quality of the Zambezi River is associated with fluctuating insect abundance, which then impacts the insectivorous birds – such as the black swift – as well as the predators that feed on these birds, such as the Taita falcon. Organochlorine pesticide sprays also cause imbalances in invertebrate communities and the insectivorous species that eat them; thus, also the availability of prey for raptors that feed on these insect-eating birds.[citation needed]

Woodland cover decreases with increased rural human settlements and light intensity agriculture and subsistence farming on both sides of Batoka Gorge.[3] These more open, disturbed habitats are better suited to other raptor species – particularly Lanner falcons – rather than the highly specialized Taita falcons. This increase in woodland fragmentation decreases the amount of suitable habitat available to these falcons, thus threatening their conservation status. Because the conservation of these birds depends on the availability of nesting sites and food, appropriate environmental conditions are essential.[3] The threat of the construction of hydroelectric power about 50 km below Victoria Falls may also pose as a serious and significant threat to the conservation of avifaunal communities in this area.[5]

The scarcity of the Taita falcon in East Africa may be owing to the competition for food and nest sites with the larger and more dominant peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) and predation of young by the peregrine falcon, lanner falcon (Falco biarmicus), and owls.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2020). "Falco fasciinucha". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22696523A174219122. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22696523A174219122.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Hartley; R., Bodington, G.; Dunkley, A.S. & Groenewald, A. (1993). "Notes on the Breeding Biology, Hunting, Behavior, and Ecology of the Taita Falcon in Zimbabwe" (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 27 (3): 133–142.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jenkins, A.R.; et al. (2019). "Status of the Taita Falcon (Falco Fasciinucha) and Other Cliff-Nesting Raptors in Batoka Gorge, Zimbabwe". Journal of Raptor Research. 53 (1): 46–55. doi:10.3356/JRR-18-36.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (2009-03-09). "Stephen Moss: Encounter with a rare bird - the Taita falcon". The Guardian.

- ^ a b "Taita Falcon (Falco fasciinucha) - BirdLife species factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to BirdLife South Africa - Taita Falcon CRITICALLY ENDANGERED IN SOUTH AFRICA". www.birdlife.org.za. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Illustrated by Kim Franklin, David Mead, and Philip Burton. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-12762-7

- A.C. Kemp (1991), Sasol Birds of Prey of Africa, New Holland Publishers Ltd.

External links

edit- Taita falcon - Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds.