Syzygium cumini, commonly known as Malabar plum,[3] Java plum,[3] black plum, jamun, jaman, jambul, or jambolan,[4][5] is an evergreen tropical tree in the flowering plant family Myrtaceae, and favored for its fruit, timber, and ornamental value.[5] It is native to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.[4][2] It can reach heights of up to 30 m (100 ft) and can live more than 100 years.[4] A rapidly growing plant, it is considered an invasive species in many world regions.[5]

| Syzygium cumini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Syzygium |

| Species: | S. cumini

|

| Binomial name | |

| Syzygium cumini | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Syzygium cumini has been introduced to areas including islands of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore.[6]

The tree was introduced to Florida and is commonly grown in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide.[5] Its fruits are eaten by various native birds and small mammals, such as jackals, civets, and fruit bats.[5]

Description

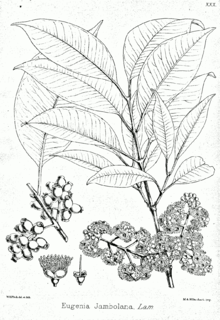

editAs a rapidly growing species, it can reach heights of up to 30 m (100 ft) and can live more than 100 years.[4] Its dense foliage provides shade and is grown just for its ornamental value. At the base of the tree, the bark is rough and dark grey, becoming lighter grey and smoother higher up. The wood is water resistant after being kiln-dried.[4] Because of this, it is used in railway sleepers and to install motors in wells. It is sometimes used to make cheap furniture and village dwellings, though it is relatively hard for carpentry.[4]

The aromatic leaves are pinkish when young, changing to a leathery, glossy dark green with a yellow midrib as they mature. The leaves are used as food for livestock, as they have good nutritional value.[7]

Syzygium cumini trees start flowering from March to April. The flowers are fragrant and small, about 5 mm (0.2 in) in diameter. The fruits develop by May or June and resemble large berries; the fruit of Syzygium species is described as "drupaceous".[8] The fruit is oblong, ovoid. Unripe fruit looks green. As it matures, its color changes to pink, then to shining crimson red and finally to black color. A variant of the tree produces white-coloured fruit. The fruit has a combination of sweet, mildly sour, and astringent flavour and tends to colour the tongue purple.[4]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 251 kJ (60 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

16 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.23 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.7 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 83 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[9] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution

editSyzygium cumini is native to the Indian subcontinent (the Andaman Islands, Bangladesh, Nepal, India, the Eastern Himalayas, Pakistan, Assam state, the Laccadive Islands and Sri Lanka); China (Hainan province, South-Central and Southeast China); Indonesia (Java, the Maluku Islands, Sulawesi); Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar); Australia (Queensland).[2]

Invasive species

editThis species is considered invasive in Florida, South Africa, parts of the Caribbean, several islands of Oceania, and Hawaii.[5][6]

Culinary uses

editJambolan fruits have a sweet or slightly acidic flavor, are eaten raw, and may be made into sauces or jam.[4] Fruits may be made into juice, jelly, sorbet, syrup (e.g., kala khatta),[11] or fruit salad.[4]

Nutrition

editRaw fruit is 83% water, 16% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and contains negligible fat. In a reference amount of 100 g (3.5 oz), the raw fruit provides 60 calories and a moderate content of vitamin C, with no other micronutrients in appreciable amounts (table).

History

editThe 1889 book The Useful Native Plants of Australia records that the plant was referred to as "durobbi" by Indigenous Australians, and that "The fruit is much eaten by the natives of India; in appearance it resembles a damson, has a harsh but sweetish flavour, somewhat astringent and acid. It is eaten by birds and is a favourite food of the flying fox (Brandis)."[12] The fruit has been used in traditional medicine.[4][5]

Cultural and religious significance in India

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

In the Majjhima Nikāya, three parallel texts (MN 36, MN 85 and MN 100) claim that the Buddha remembered an experience of sitting in the cool shade of a jambu tree when he was a child. While his father was working, he entered into a meditative state which he later understood to be the first stage of Jhāna meditation. The texts claim that this was a formative experience, which later encouraged him to explore and practise Jhāna meditation, and that this then led to his Awakening. The Pāli word jambu is understood by Pāli dictionaries to refer to the Syzygium cumini which they often translate as the Rose-apple tree.[13]

Krishna was said to have four symbols of the jambu fruit on his right foot as mentioned in the Srimad Bhagavatam commentary (verse 10.30.25), "Sri Rupa Chintamani" and "Ananda Candrika" by Srila Visvanatha Chakravarti Thakura.[14]

In Maharashtra, Syzygium cumini leaves are used in marriage pandal decorations. A song from the 1977 film Jait Re Jait mentions the fruit in the song "Jambhul Piklya Zaadakhali".

Besides the fruits, wood from neredu tree (as it is called in the region's language, Telugu) is used in Andhra Pradesh to make bullock cart wheels and other agricultural equipment. The timber of neredu is used to construct doors and windows.

Legend in Tamil Nadu speaks of Avvaiyar (also Auvaiyar or Auvayar) of the Sangam period and the jamun fruit, called naval pazham in Tamil. Avvaiyar, believing to have achieved everything that is to be achieved, is said to have been pondering over her retirement from Tamil literary work while resting under naval pazham tree. There she was met with and was wittily jousted by a disguised Murugan, regarded as one of the guardian deities of Tamil language, who later revealed himself and made her realize that there is still a lot more to be done and learnt.[15]

Gallery

edit-

Saplings

-

A line of mature trees

-

Close view of foliage

-

Young plant

-

Seeds

-

Seeds

-

Flower buds and open flowers

-

Fruits in various stages of ripeness

-

Fruits

-

Fruit

-

Ripe fruits for sale in a market

-

Ripe fruits for sale in a local market of Nepal.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI).; IUCN SSC Global Tree Specialist Group (2019). "Syzygium cumini". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T49487196A145821979. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T49487196A145821979.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Syzygium cumini". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Julia F Morton (1987). "Jambolan, Syzygium cumini Skeels". In: Fruits of Warm Climates, p. 375–378; NewCROP, New Crop Resource Online Program, Center for New Crops and Plant Products, Purdue University. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Syzygium cumini (black plum)". CABI. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Syzygium cumini". Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk. 30 December 2011.

- ^ The encyclopedia of fruit & nuts, By Jules Janick, Robert E. Paull, p. 552

- ^ Chen, Jie & Craven, Lyn A., "Syzygium", in Wu, Zhengyi; Raven, Peter H. & Hong, Deyuan (eds.), Flora of China (online), eFloras.org, retrieved 2015-08-13

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ "What is Kala Khatta Syrup ? Glossary | Benefits, Uses, Recipes with Kala Khatta Syrup |".

- ^ J. H. Maiden (1889). The useful native plants of Australia : Including Tasmania. Turner and Henderson, Sydney.

- ^ Rhys-Davids, Pali-English Dictionary; Cone, Dictionary of Pali

- ^ Vishvanatha, Cakravarti Thakura (2011). Sarartha-darsini (Bhanu Swami ed.). Sri Vaikunta Enterprises. p. 790. ISBN 978-81-89564-13-1.

- ^ Ramadevi, B. (3 March 2014). "The saint of the masses". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021.

External links

edit- Media related to Syzygium cumini at Wikimedia Commons

- "Syzygium cumini". Plants for a Future.