Enochian (/ɪˈnoʊkiən/ ə-NOH-kee-ən) is an occult constructed language[3]—said by its originators to have been received from angels—recorded in the private journals of John Dee and his colleague Edward Kelley in late 16th-century England.[4] Kelley was a scryer who worked with Dee in his magical investigations. The language is integral to the practice of Enochian magic.

| Enochian | |

|---|---|

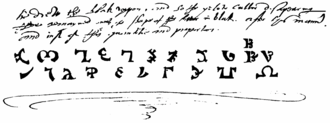

John Dee’s manuscript diary for 6 May 1583, showing the 21 letters of the Enochian script | |

| Created by | John Dee Edward Kelley |

| Date | 1583–1584 |

| Setting and usage | Occult journals |

| Purpose | Divine language

|

| Latin script, Enochian script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | i-enochian (deprecated)[1][2] |

The language found in Dee's and Kelley's journals encompasses a limited textual corpus. Linguist Donald Laycock, an Australian Skeptic, studied the Enochian journals, and argues against any extraordinary features. The untranslated texts of the Liber Loagaeth manuscript recall the patterns of glossolalia rather than true language. Dee did not distinguish the Liber Loagaeth material from the translated language of the Calls, which is more like an artificial language. This language was called Angelical by Dee and later came to be referred to as "Enochian" by subsequent writers. The phonology and grammar resemble English, though the translations are not sufficient to work out any regular morphology.[5] Some Enochian words resemble words and proper names in the Bible, but most have no apparent etymology.[6]

Dee's journals also refer to this language as "Celestial Speech", "First Language of God-Christ", "Holy Language", or "Language of Angels". He also referred to it as "Adamical" because, according to Dee's angels, it was used by Adam in Paradise to name all things. The term "Enochian" comes from Dee's assertion that the Biblical patriarch Enoch had been the last human (before Dee and Kelley) to know the language.

History

editAccording to Tobias Churton in his text The Golden Builders,[7] the concept of an Angelic or antediluvian language was common during Dee's time. If one could speak the language of angels, it was believed one could directly interact with them.

Seeking contact and reported visions

editIn 1581, Dee mentioned in his personal journals that God had sent "good angels" to communicate directly with prophets. In 1582, Dee teamed up with the seer Edward Kelley, although Dee had used several other seers previously.[8] With Kelley's help as a scryer, Dee set out to establish lasting contact with the angels. Their work resulted, among other things, in the reception of Angelical, now more commonly known as Enochian.[9]

The reception started on March 26, 1583, when Kelley reported visions in the crystal of a 21-lettered alphabet. A few days later, Kelley started receiving what became the book Liber Loagaeth ("Book [of] Speech from God"). The book consists of 49 great letter tables, or squares made of 49 by 49 letters. (However, each table has a front and a back side, making 98 tables of 49×49 letters altogether.)[a] Dee and Kelley said the angels never translated the texts in this book.[citation needed]

Receiving the Angelic Keys

editAbout a year later, at the court of King Stephen Báthory in Kraków, where both alchemists stayed for some time, another set of texts was reportedly received through Kelley.[citation needed] These texts comprise 48 poetic verses with English translations, which in Dee's manuscripts are called Claves Angelicae, or Angelic Keys. Dee was apparently intending to use these Keys to open the "Gates of Understanding"[10] represented by the magic squares in Liber Loagaeth:

I am therefore to instruct and inform you, according to your Doctrine delivered, which is contained in 49 Tables. In 49 voices, or callings: which are the Natural Keys to open those, not 49 but 48 (for one is not to be opened) Gates of Understanding, whereby you shall have knowledge to move every Gate...[11]

— The angel Nalvage

But you shall understand that these 19 Calls are the Calls, or entrances into the knowledge of the mystical Tables. Every Table containing one whole leaf, whereunto you need no other circumstances.[12]

— The angel Illemese

Phonology and writing system

editThe language was recorded primarily in Latin script. However, individual words written in Enochian script "appear sporadically throughout the manuscripts".[13] There are 21 letters in the script; one letter appears with or without a diacritic dot. Dee mapped these letters of the "Adamical alphabet" onto 22 of the letters of the English alphabet, treating U and V as positional variants (as was common at the time) and omitting the English letters J, K, and W.[b] The Enochian script is written from right to left in John Dee's diary.[14] Different documents have slightly different forms of the script. The alphabet also shares many graphical similarities to a script, also attributed to the prophet Enoch, that appeared in the Voarchadumia Contra Alchimiam of Johannes Pantheus,[15] a copy of which Dee is known to have owned.[13]

The phonology of Enochian is "thoroughly English", apart from difficult sequences such as bdrios, excolphabmartbh, longamphlg, lapch, etc.[16] Similarly, Enochian orthography closely follows Early Modern English orthography, for example in having soft and hard ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩, and in using digraphs ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨sh⟩, and ⟨th⟩ for the sounds /tʃ ~ k/, /f/, /ʃ/, and /θ/.[17] Laycock mapped Enochian orthography to its sound system and says, "the resulting pronunciation makes it sound much more like English than it looks at first sight".[18][c] However, the difficult strings of consonants and vowels in words such as ooaona, paombd, smnad and noncf are the kind of pattern one gets by joining letters from a text together in an arbitrary pattern. As Laycock notes, "The reader can test this by taking, for example, every tenth letter on this page, and dividing the string of letters into words. The 'text' created will tend to look rather like Enochian."[19]

- Alphabet

The Enochian letters, with their letter names and English equivalents as given by Dee, and pronunciations as reconstructed by Laycock, are as follows.[b] Modern pronunciation conventions vary, depending on the affiliations of the practitioner.[d]

| Letter | Letter name |

English equivalent |

Enochian phonology[20] | Golden Dawn syllabic reading[21][α] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Un | A | long [ɑː] (stressed), short [a] (unstressed) | [ɑː] | |

| Pa | B | [b]; silent after m when before another consonant or final | [beɪ] | |

| Veh | C | [k] before a, o, u; [s] before e, i and in consonant clusters, with many exceptions; ⟨ch⟩ as [k] in most positions but [tʃ] finally. |

? | |

| Gal | D | [d] | [deɪ] | |

| Graph | E | [eː] (stressed), [ɛ] (unstressed) | [eɪ] | |

| Or | F | [f] | [ɛf] | |

| Ged | G | [ɡ] before a, o, u; [dʒ] before e, i, finally, after d, and in consonant clusters. | ? | |

| Na | H | [h] except in ⟨ch⟩, ⟨ph⟩, ⟨sh⟩, ⟨th⟩; silent after a vowel (in which case the vowel is "lengthened" – that is, has the sound it would have if stressed) |

[heɪ] | |

| Gon | I | [j] word-initially before a vowel; as a vowel: [iː] (stressed), [ɪ] (unstressed), plus diphthongs ai [aɪ], ei [eɪ], oi [oɪ] |

[iː] | |

| Y | [j] | (same as I) | ||

| Ur | L | [l] | ? | |

| Tal | M | [m] | [ɛm] | |

| Drux | N | [n] | [ɛn], [nuː] | |

| Med | O | [oː] (stressed), [ɒ] (unstressed) | [oʊ] | |

| Mals | P | [p] but for ⟨ph⟩, which is [f] | [peɪ] | |

| Ger | Q | [kw]; the word q is [kwɑː] | ? | |

| Don | R | [r] | [ɑː(r)], [rɑː] | |

| Fam | S | [s] or [z] as would be natural in English, but for ⟨sh⟩, which is [ʃ] | [ɛs] | |

| Gisg | T | [t] but for ⟨th⟩, which is [θ] | [teɪ] | |

| Van | U/V | [uː] (stressed) or [ʊ] (unstressed); [juː] in initial position; [v] or [w] before another vowel and word-finally | ? | |

| Pal | X | [ks] | [ɛks] | |

| Ceph | Z | [z], rarely [zɒd] | [zɒd] |

- ^ According to Wynn Wescott, each letter may be pronounced separately as its name in English or sometimes as the first consonant and vowel of its Hebrew name, e.g. N may be [ɛn] or [nu] (from nun). However, consonants-vowel sequences may be optionally run together into single syllables. E.g. ta may be pronounced [teɪ ɑː] or [tɑː]; co, [koʊ]; ar, [ɑːr]; re, [reɪ].[21]

A number of fonts for the Enochian script are available. They use the ASCII range, with the letters assigned to the codepoints of their English equivalents.[22][23][24][25]

Grammar

editMorphology

editThe grammar is for the most part without articles or prepositions.[5][26] Adjectives are quite rare.[27] Aaron Leitch identifies several affixes in Enochian, including -o (indicating 'of') and -ax (which functions like -ing in English).[28] Leitch observes that, unlike English, Enochian appears to have a vocative case, citing Dee's note in the margin of the First Table of Loagaeth[29] – "Befes the vocative case of Befafes".[30]

Compounds

editCompounds are frequent in the Enochian corpus. Modifiers and indicators are typically compounded with the nouns and verbs modified or indicated. These compounds can occur with demonstrative pronouns and conjunctions, as well as with various forms of the verb 'to be'. The compounding of nouns with adjectives or other verbs is less common. Compounds may exhibit variant spellings of the words combined.[31]

Conjugation

editConjugation can result in spelling changes which can appear to be random or haphazard. Due to this, Aaron Leitch has expressed doubt as to whether Enochian actually has conjugations.[32] The very scant evidence of Enochian verb conjugation seems quite reminiscent of English, including the verb 'to be' which is highly irregular.[5]

Laycock reports that the largest number of forms are recorded for 'be' and for goh- 'say':[5]

'to be' zir, zirdo I am geh thou art i he/she/it is chiis, chis, chiso they are as, zirop was zirom were trian shall be christeos let there be bolp be thou! ipam is not ipamis cannot be

| 'to say' | |

|---|---|

| gohus | I say |

| gohe, goho | he says |

| gohia | we say |

| gohol | saying |

| gohon | they have spoken |

| gohulim | it is said |

Note that christeos 'let there be' might be from 'Christ', and if so is not part of a conjugation.[6]

For negation of verbs, two constructions are attested: e.g. chis ge 'are not' (chis 'they are') and ip uran 'not see' (uran 'see').[5]

Pronouns

editWhile Enochian does have personal pronouns, they are rare and used in ways that can be difficult to understand. Relative possessive pronouns do exist but are used sparingly.[27]

Attested personal pronouns (Dee's material only):[33]

ol I, me, my, myself il, ils, yls, ylsi thou, thee q ([kwɑ]) thy tia his tox of him, his pi she tlb = tilb, tbl ([tibl]) her, of her tiobl in her t ([ti]) it

| zylna | itself |

| ge | we, us, our (soft 'g') |

| helech | in ours (?) |

| g = gi | you, your (soft 'g') |

| nonci | you (soft 'c') |

| nonca, noncf, noncp | to you (soft 'c') |

| amiran | yourselves |

| z ([zə]) | they |

| par | they, them |

Demonstrative pronouns: oi 'this', unal 'these, those', priaz(i) 'those'.[34]

Syntax

editWord order closely follows English, except for the dearth of articles and prepositions.[5] Adjectives, although rare, typically precede the noun as in English.[27]

Vocabulary and corpus

editLaycock notes that there are about 250 different words in the corpus of Enochian texts, more than half of which occur only once. A few resemble words in the Bible – mostly proper names – in both sound and meaning. For example, luciftias "brightness" resembles Lucifer "the light-bearer"; babalond "wicked, harlot" resembles Babylon.[6] Leitch notes a number of root words in Enochian. He lists Doh, I, Ia, Iad,[clarification needed] among others, as likely root words.[35][what do they mean?] While the Angelic Keys contain most of the known vocabulary of Enochian, dozens of further words are found throughout Dee's journals.

Thousands of additional, undefined words are contained in the Liber Loagaeth. Laycock notes that the material in Liber Loagaeth appears to be different from the language of the 'Calls' found in the Angelic Keys, which appear to have been generated from the tables and squares of the Loagaeth.[5] According to Laycock:

The texts in the Loagaeth show patterning "characteristically found in certain types of meaningless language (such as glossolalia), which is often produced under conditions similar to trance. In other words, Kelley may have been 'speaking in tongues'. [...] there is no evidence that these early invocations are any form of 'language' [...] at all.[36]

Dictionaries

editThere have been several compilations of Enochian words made to form Enochian dictionaries. A scholarly study is Donald Laycock's The Complete Enochian Dictionary.[37] Also useful is Vinci's Gmicalzoma: An Enochian Dictionary.[38]

Representation of numbers

editThe number system is inexplicable. It seems possible to identify the numerals from 0 to 10:[39]

- 0 – T

- 1 – L, EL, L-O, ELO, LA, LI, LIL

- 2 – V, VI-I-V, VI-VI

- 3 – D, R

- 4 – S, ES

- 5 – O

- 6 – N, NORZ

- 7 – Q

- 8 – P

- 9 – M, EM

- 10 – X

However, Enochian texts contain larger numbers written in alphabetical form, and there is no discernible system behind them:[39]

|

|

As Laycock put it, "the test of any future spirit-revelation of the Enochian language will be the explanation of this numerical system."[39]

Relation to other languages

editDee believed Enochian to be the Adamic language universally spoken before the confusion of tongues. However, modern analysis shows Enochian to be an English-like constructed language.[3] Word order closely follows English, except for the dearth of articles and prepositions.[5] The very scant evidence of Enochian verb conjugation is likewise reminiscent of English, more so than with Semitic languages such as Hebrew, which Dee said were debased versions of the Enochian language.[5]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ This book is now in the British Library, MS Sloane 3189.

- ^ a b Dee's table in Loagaeth (MS Sloane 3189) as reproduced in Magickal Review (2005).

- ^ Laycock (2001), p. 45: "As the texts dictated in Enochian consist of a series of 'Calls', or invocations of supernatural beings, it was clearly necessary for Dee and Kelley to know how the words should be uttered; in most magical systems, a slight error in the text of a spell or invocation is regarded as potentially leading to disastrous consequences. Accordingly, Dee was in the habit of writing the pronunciation of the Enochian words alongside the text. … his intention is usually quite clear. He writes dg when he means 'soft g (as in gem); and s for 'soft c; and he indicates in some places that ch is to be pronounced as k. He marks the stressed vowels in most words. … In more difficult cases, he gives examples from English, thus, zorge is said to be pronounced to rhyme with 'George'. … With all of these instructions, we can get a fairly good idea of how Enochian sounded to Dee and Kelley. We have to make allowances, of course, for the fact that the two men spoke English of more than four centuries ago … Fortunately, linguists are in the possession of sufficient evidence … to establish the pronunciation of most forms of Elizabethan English with a high degree of accuracy."

- ^ DuQuette (2019), p. 197: "[...] by and large, we modern magicians are left to our own devices as to how to push these awkwardly constructed words out of our mouths. [...] The Golden Dawn and Crowley use a pronunciation that they felt rolled more fluidly off the tongue. This method obliged the magician to insert a natural Hebrew vowel sound after every Enochian consonant. [...] The most obvious alternative to the GD pronunciation is simply sounding out the words as they are written [...] This is what I have done, and what I recommend to students who are learning Enochian magick."

References

editCitations

edit- ^ "Language Subtag Registry". Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ "Language Subtag Registration Form for 'i-enochian'". Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ a b Bowern & Lindemann (2021).

- ^ The Private Diary of Dr. John Dee by John Dee at Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Laycock (2001), p. 43.

- ^ a b c Laycock (2001), p. 42.

- ^ Churton (2002).

- ^ Harkness (1999), p. 16-17.

- ^ Leitch (2010b).

- ^ Dee (1659), p. 77.

- ^ The angel Nalvage, cited in Dee (1992), p. 77.

- ^ The angel Illemese, cited in Dee (1992), p. 199.

- ^ a b Laycock (2001), p. 28.

- ^ Dee (1582).

- ^ Pantheus (1550), p. 15v-16r.

- ^ Laycock (2001), p. 33, 41.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), p. 23-24.

- ^ Laycock (2001), p. 46.

- ^ Laycock (2001), p. 40-41.

- ^ Laycock (2001), pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Laycock (2001), p. 60.

- ^ "Enochian Materials". The Magickal Review. Archived from the original on 2007-08-26.

- ^ Gerald J. Schueler, Betty Jane Schueler (2001). "Download fonts". Schueler's Online.

- ^ James A. Eshelman (2001). "Enochian Elemental Tablets". AumHa.

- ^ "Enochian Font". Esoteric Order of the Golden Dawn. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), p. 20.

- ^ a b c Leitch (2010b), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), p. 21.

- ^ Dee & Peterson (2003), p. 310.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), pp. 15–17.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Laycock (2001), p. 43 and dictionary entries.

- ^ Laycock (2001), p. dictionary entries.

- ^ Leitch (2010b), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Laycock (2001), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Laycock (2001).

- ^ Vinci (1992).

- ^ a b c Laycock (2001), pp. 44.

Works cited

editPrimary sources

edit- Dee, John (1582). "Sloane MS 3188". British Library.

- Dee, John (1659). A True & Faithful Relation of what Passed for Many Yeers Between Dr. John Dee and Some Spirits. Antonine Publishing Company.

- Dee, John (1992). Casaubon, Meric (ed.). A True and Faithful Relation of What Passed for Many Years Between John Dee and Some Spirits. New York: Magickal Childe Publishing.

- Dee, John; Peterson, Joseph H. (2003). John Dee's Five Books of Mystery: Original Sourcebook of Enochian Magic: From the Collected Works Known as Mysteriorum Libri Quinque. Boston: Weiser Books. ISBN 1578631785.

- Pantheus, Johannes (1550). Voarchadumia Contra Alchimiam. p. 15v-16r. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08 – via Scribd.com.

Secondary sources

edit- Bowern, Claire L.; Lindemann, Luke (January 2021). "The Linguistics of the Voynich Manuscript". Annual Review of Linguistics. 7: 285–308. doi:10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030613. S2CID 228894621.

- Churton, Tobias (2002). The Golden Builders. Signal Publishing. ISBN 0-9543309-0-0.

- DuQuette, Lon Milo (2019). Enochian Vision Magick: A Practical Guide to the Magick of Dr. John Dee and Edward Kelley. Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 978-1578636846.

- Harkness, Deborah (1999). John Dee's Conversations with Angels: Cabala, Alchemy, and the End of Nature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521622288.

- Laycock, Donald (2001). The Complete Enochian Dictionary: A Dictionary of the Angelic Language As Revealed to Dr. John Dee and Edward Kelley. Boston: Weiser. ISBN 1578632544.

- Leitch, Aaron (2010b). The Angelical Language, Volume II: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the Tongue of Angels. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0738714912.

- Magickal Review, ed. (2005). "The Angelic or Enochian Alphabet". The Magickal Review. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12.

- Vinci, Leon (1992) [1976]. Gmicalzoma: An Enochian Dictionary. London: Neptune Press.

Further reading

edit- Asprem, Egil (December 13, 2006). ""Enochian" language: A proof of the existence of angels?". Skepsis. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- Eco, Umberto (1997). The Search for the Perfect Language. London: Fontana Press. ISBN 0006863787.

- James, Geoffrey (2009), The Enochian Evocation of Dr. John Dee, Newburyport, MA: Weiser Books, ISBN 978-1578634538.

- Johnson, Christopher Reed (May 29, 2024). "Enochian Magick: Chris Johnson's Path into the Angelic Mysteries". Perseus Academy. Retrieved 2024-10-02.

- Leitch, Aaron (2010a). The Angelical Language, Volume I: The Complete History and Mythos of the Tongue of Angels. Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 978-0738714905.

- Norrgrén, H. (2005). "Interpretation and the Hieroglyphic Monad: John Dee's Reading of Pantheus's Voarchadumia". Ambix. 52 (3): 217–245. doi:10.1179/000269805X77781. S2CID 170087190.

- Sledge, J. J. (2010). "Between Loagaeth and Cosening: Towards an Etiology of John Dee's Spirit Diaries". Aries. 10 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1163/156798910X12584583444835.

- Turner, P. S.; Turner, R.; Cousins, R. E. (1989). Elizabethan Magic: The Art and the Magus. Element. ISBN 978-1852300838.

- Tyson, Donald (1997). Enochian Magic for Beginners: The Original System of Angel Magic. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 1567187471.

- Yates, Frances (1979). The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415254094.