Elefsina (Greek: Ελευσίνα, romanized: Elefsína) or Eleusis (/ɪˈljuːsɪs/ ih-LEW-siss;[3] Ancient Greek: Ἐλευσίς, romanized: Eleusís) is a suburban city and municipality in Athens metropolitan area. It belongs to West Attica regional unit of Greece. It is located in the Thriasio Plain, at the northernmost end of the Saronic Gulf. North of Elefsina are Mandra and Magoula, while Aspropyrgos is to the northeast.

Elefsina

Ελευσίνα | |

|---|---|

View over the excavation site towards Elefsina. | |

| Coordinates: 38°2′N 23°32′E / 38.033°N 23.533°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Attica |

| Regional unit | West Attica |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Georgios Georgopoulos[1] (since 2023) |

| Area | |

• Municipality | 36.589 km2 (14.127 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 18.455 km2 (7.126 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population (2021)[2] | |

• Municipality | 30,147 |

| • Density | 820/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 24,971 |

| • Municipal unit density | 1,400/km2 (3,500/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 192 00 |

| Area code(s) | 210 |

| Vehicle registration | YP, YT |

| Website | elefsina |

It is the site of the Eleusinian Mysteries and the birthplace of Aeschylus. Today, Elefsina is a major industrial centre, with the largest oil refinery in Greece as well as the home of the Aeschylia Festival, the longest-lived arts event in the Attica Region. On 11 November 2016, Elefsina was named the European Capital of Culture for 2021, which became effective in 2023 due to the COVID-19 pandemic postponement.

Etymology

editThe word Eleusis first appears in the Orphic Hymn to Eleusinian Demeter: «Δήμητρος Ελευσινίας, θυμίαμα στύρακα[4]». Also Hesychius of Alexandria reports that the older name for Eleusis was Saesara (Σαισάρια). Saesara was the mythic daughter of Celeus (king of Eleusis when Demeter arrived for the first time) and granddaughter of Eleusinus, the first settler of Eleusis.[5]

Municipality

editThe municipality of Elefsina was formed at the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following two former municipalities, that became municipal units:[6]

- Elefsina

- Magoula

The municipality has an area of 36.589 km2 (14.127 sq mi), and the municipal unit has an area of 18.455 km2 (7.126 sq mi).[7]

History

editAncient

editEleusis was a deme of ancient Attica, belonging to the phyle Hippothoöntis. It owed its celebrity to its being the chief seat of the worship of Demeter and Persephone, and to the mysteries celebrated in honour of these goddesses, which were called the Eleusinia, and continued to be regarded as the most sacred of all the Grecian mysteries down to the fall of paganism.

Eleusis stood upon a height at a short distance from the sea, and opposite the island of Salamis.[8] Its situation possessed three natural advantages. It was on the road from Athens to the Isthmus of Corinth; it was in a very fertile plain; and it was at the head of an extensive bay, formed on three sides by the coast of Attica, and shut in on the south by the island of Salamis. The town itself dates from the most ancient times.

The caves on the coast of Eleusis are home to a mythological place for the Greek world. There is a cave said to be the very spot where Persephone was abducted by Hades himself and the cave was considered a gateway to Tartarus. At the spot of this abduction was a sanctuary (Ploutonion) dedicated to Hades and Persephone.[9]

The Rharian plain is also mentioned in the Homeric Hymn to Artemis;[10] it appears to have been in the neighbourhood of the city; but its site cannot be determined.

Mythology and Proto-history

editIt appears to have derived its name from the supposed advent (ἔλευσις) of Demeter, though some traced its name from an eponymous hero Eleusis.[11] It was one of the 12 independent states into which Attica was said to have been originally divided.[12]

"When Athens had only just become Athens, it went to war with another city built thirteen miles away: Eleusis," Roberto Calasso wrote of the ancient provenance of the relationship between temple-city and the Attic seat of power.[13] "It was a war usually described as mythical, since it has no date. And it was a theological war, since Athens belonged to Athena and Eleusis to Poseidon. Eumolpus and Erechtheus, the founding kings of the two cities, both died in it."[13]

It is related that in the reign of Eumolpus, king of Eleusis, and Erechtheus, king of Athens, there was a war between the two states, in which the Eleusinians were defeated, whereupon they agreed to acknowledge the supremacy of Athens in everything except the celebration of the mysteries, of which they were to continue to have the management.[14][15] Eleusis afterwards became an Attic deme, but in consequence of its sacred character it was allowed to retain the title of polis (πόλις)[16][11] and to coin its own money, a privilege possessed by no other town in Attica, except Athens. The history of Eleusis is part of the history of Athens. Once a year the great Eleusinian procession travelled from Athens to Eleusis, along the Sacred Way.

Eleusinian Mysteries

editEleusis was the site of the Eleusinian Mysteries, or the Mysteries of Demeter and Kore, which became popular in the Greek-speaking world as early as 600 BC, and attracted initiates during Roman Empire before declining mid-late 4th century AD.[17] These Mysteries revolved around a belief that there was a hope for life after death for those who were initiated. Such a belief was cultivated from the introduction ceremony in which the hopeful initiates were shown a number of things including the seed of life in a stalk of grain. The central myth of the Mysteries was Demeter's quest for her lost daughter (Kore the Maiden, or Persephone) who had been abducted by Hades. It was here that Demeter, disguised as an old lady who was abducted by pirates in Crete, came to an old well where the four daughters of the local king Keleos and his queen Metaneira (Kallidike, Kleisidike, Demo and Kallithoe) found her and took her to their palace to nurse the son of Keleos and Metaneira, Demophoon. Demeter raised Demophoon, anointing him with nectar and ambrosia and placing him at night in the fire in order to endow him with immortality, until Metaneira found out and insulted her. Demeter arose insulted, and casting off her disguise, and, in all her glory, instructed Meteneira to build a temple to her. Keleos, informed the next morning by Metaneira, ordered the citizens to build a rich shrine to Demeter, where she sat in her temple until the lot of the world prayed to Zeus to make the world provide food again.

The Great Eleusian relief which was famous in antiquity and was copied in the Roman period, is the largest and most important votive relief found and dates to 440-430 BC. It represents the Eleusinian deities in a scene depicting a mysterious ritual. On the left Demeter, clad in a peplos and holding a sceptre in her left hand, offers ears of wheat to Triptolemos, son of Eleusinian king Keleos, to bestow on mankind. On the right Persephone, clad in chiton and mantle and holding a torch, blesses Triptolemos with her right hand. The original marble relief was found at the sanctuary of Demeter, the site of the Eleusinian mysteries. A number of Roman copies also survive.[18]

Greek and Roman History

editDuring the Greco-Persian Wars, the ancient temple of Demeter was burnt down by the Persians in 484 BC;[19] and it was not until the administration of Pericles that an attempt was made to rebuild it. When the power of the Thirty Tyrants was overthrown after the Peloponnesian War, they retired to Eleusis, which they had secured beforehand, but where they maintained themselves for only a short time.[20]

The town of Eleusis and its immediate neighbourhood were exposed to inundations from the river Cephissus, which, though almost dry during the greater part of the year, is sometimes swollen to such an extent as to spread itself over a large part of the plain. Demosthenes (384 – 322 BC) alludes to inundations at Eleusis;[21]

Pausanias (c. 110 – c. 180 AD) has left us only a very brief description of Eleusis;[22]

The Eleusinians have a temple of Triptolemus, another of Artemis Propylaea, and a third of Poseidon the Father, and a well called Callichorum, where the Eleusinian women first instituted a dance and sang in honour of the goddess. They say that the Rharian plain was the first place in which corn was sown and first produced a harvest, and that hence barley from this plain is employed for making sacrificial cakes. There the so-called threshing-floor and altar of Triptolemus are shown. The things within the wall of the Hierum [i.e., the temple of Demeter] a dream forbade me to describe.

Under the Romans Eleusis enjoyed great prosperity, as initiation into its mysteries became fashionable among the Roman nobles.

Hadrian was initiated into the Mysteries in about 125[23] and raised embankments in the plain of the river in consequence of a flood which occurred while he was spending the winter at Athens.[24]

To the same emperor most likely Eleusis was indebted for a supply of good water by means of the aqueduct, completed in about 160 AD. Apart from satisfying the need for drinking water, it also enabled the construction of public fountains and baths. It was fed by springs in Mount Parnitha and used mainly underground tunnels. It crossed the Thriasian Plain and turned abruptly towards the south at the outskirts of Eleusis. The best visible remains are on the east side of Dimitros Street.

It was destroyed by Alaric I in 396 AD, and from that time disappears from history.

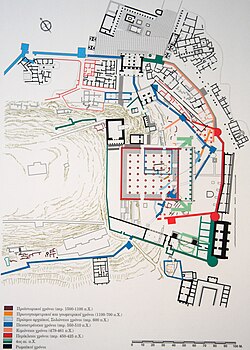

Monuments

editThe Telesterion, or temple of Demeter, was the largest in all Greece,[citation needed] and is described by Strabo as capable of containing as many persons as a theatre.[25] The building was initially designed by Ictinus, the architect of the Parthenon at Athens; but it was many years before it was completed, and the names of several architects are preserved who were employed in building it.

During its long history, the temple underwent subsequent building phases. Much of that visible today is of the Classical era (5th century BC). Its portico of 12 columns was added in the time of Demetrius Phalereus, about 318 BC, by the architect Philo.[25][26] When finished, it was considered one of the four finest examples of Grecian architecture in marble.

Modifications were also carried out in Roman times (2nd c. AD).

The Roman bridge that carried the ancient Sacred Way over the Kephissus river is visible about 1 km from the Sanctuary of Demeter. The bridge is in very good condition and is an outstanding example of ancient bridge building. It consists of a central 30 m-long main bridge with 4 arches and 10 m-long sloping access on either side.

The Sacred Way was the main road from Athens and led to Demeter's sanctuary, and was also the road used by the procession every year of the celebration of the Great Mysteries escorting the sacred objects back to Eleusis. Its course is visible in some places and has been accurately traced by rescue excavations and ran parallel to its namesake in the modern city only a few metres to the south. Roadside cemeteries from different periods throughout antiquity are found next to it and prehistoric graves witness its existence by 1600 BC. During the Hellenistic and mainly Roman eras the road was used for the exhibition of wealth and social power, with costly burial monuments being erected all along it. The road was in use until at least the 6th century AD.

Medieval and early Modern era

editIt is indicative that writers of the Byzantine era refer to it as a "small village", and shortly before the Ottoman domination the area was deserted by wars, raids and captives. During this period was settled by Arvanites. European travelers during the Ottoman domination described Eleusis as having few inhabitants and many ancient ruins.

Modern Elefsina

editIn 1829, after the Greek War of Independence, Elefsina was a small settlement of about 250 inhabitants. By the late 19th century Elefsina changed drastically as new buildings were erected by the new merchant settlers. Also during that period Eleusis became one of the main industrial centers of the Modern Greek state with concrete factory TITAN, Charilaou Soap Factory as well as the distilleries of Botrys and Kronos being established in the area.[27]

Arvanitika is still spoken in the village, with the locals qualifying their dialect more "noble" and "refined" than those of rural Arvanites.[28] Many Greek families of Asia Minor settled in Elefsina after the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe and created the settlement of Upper Elefsina, doubling its total population and enriching the region culturally and economically.[29]

During the Axis occupation of Greece (1941–1945), strong resistance developed within the city, the factories and the military airport, which once stationed Squadron 80, the squadron that Roald Dahl[30] was assigned to in the RAF. After World War II, workers from all parts of Greece moved to Elefsina to work in the industries in the region. Industrial activity, however, developed anarchically on the antiquities and next to the residential area.

Environmental pollution has taken on large dimensions. During the 20th century, at the time of sustainable development, archaeological discoveries and industrial formation shaped the image of contemporary Eleusis.

In 1962, a large house of priests from the Roman era was discovered. Pollution thanks to citizens' struggles gradually has fallen.

Today, the city has become a suburb of Athens, to which it is linked by the A6 motorway and Greek National Road 8. Eleusis is nowadays a major industrial area, and the place where the majority of crude oil in Greece is imported and refined. The largest refinery is located on the west side of town, right beside where the annual Aeschylia Festival is held in honor of the great tragic poet Aeschylus.

Elefsis Shipyards is located here.

There is a military airport a few kilometers east of Elefsina. Elefsina Airfield played a crucial role in the final British evacuation during the 1941 Battle of Greece, as recounted by Roald Dahl in his autobiography Going Solo.

Elefsina is home to the football club Panelefsiniakos F.C., and the basketball club Panelefsiniakos B.C.

Aeschylia Festival

editEstablished in 1975, the Aeschylia Festival in Eleusis in Western Attica is the currently the longest standing cultural event organized by an Attica Municipality. It is held annually at Palaio Elaiourgeio, a former soap factory by the seafront that functions as an open theatre. The festival usually is running at the end of August and during all of the September. The event is organized in honor of Aeschylus, who was born in Eleusis, from whom it derives its name. It includes stage productions, art exhibitions and installations, concerts, and dance events.

Climate

editElefsina has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa), bordering on a hot semi-arid climate (BSh) for the 1958-2010 period, according to the meteorological station operated by the Hellenic National Meteorological Service. Elefsina is particularly hot during the summer, with an average July maximum of 33.2 °C (91.8 °F). According to Kassomenos and Katsoulis (2006), based on 12 years of data (1990–2001), the industrialization of west Attica, where at least 40% of the industrial activity of the country is concentrated, could be the cause of the warm climate of the zone.[31] On June 4, 2024 the WMO station in the port of Elefsina broke the record for the highest temperature ever recorded in Greece for the first 10 days of June from the National Observatory of Athens network. [32]

| Climate data for Elefsina Port 10 m a.s.l. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.9 (76.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

31.4 (88.5) |

37.4 (99.3) |

45.3 (113.5) |

44.8 (112.6) |

43.7 (110.7) |

38.4 (101.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

29.1 (84.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

45.3 (113.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.1 (93.4) |

29.7 (85.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.7 (67.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

4.5 (40.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 60.4 (2.38) |

33.6 (1.32) |

24.6 (0.97) |

20.3 (0.80) |

19.4 (0.76) |

33.1 (1.30) |

11.1 (0.44) |

10.5 (0.41) |

32.3 (1.27) |

28.9 (1.14) |

65.6 (2.58) |

57.5 (2.26) |

397.3 (15.63) |

| Source: National Observatory of Athens Monthly Bulletins (Mar 2016-Apr 2024)[33][34] and World Meteorological Organization[35] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Elefsina, Greece (1958–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

28.8 (83.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

22.6 (72.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.3 (45.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 48.4 (1.91) |

37.6 (1.48) |

38.9 (1.53) |

26.0 (1.02) |

18.2 (0.72) |

8.0 (0.31) |

5.7 (0.22) |

5.0 (0.20) |

15.7 (0.62) |

47.3 (1.86) |

63.4 (2.50) |

62.9 (2.48) |

377.1 (14.85) |

| Source: Hellenic National Meteorological Service[36] | |||||||||||||

European temperature record

editUntil 2021, Elefsina was one of the areas in the Athens Metropolitan Area (the other one was Tatoi) which held the record of the highest ever officially recorded temperature in Europe for 44 years with a reading of 48.0 °C (118.4 °F) on 10 July 1977.[37]

Hospitals and medical centres

editElefsina has only one general hospital the Thriassio General Hospital, located 3.9 km north of the city centre.

Historical population

edit| Year | Municipal unit | Municipality |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 20,320 | – |

| 1991 | 22,793 | – |

| 2001 | 25,863 | – |

| 2011 | 24,901 | 29,902 |

| 2021 | 24,971 | 30,147 |

Sports

editElefsina hosts the multi-sport club Panelefsiniakos with successful sections in football and basketball. Another historical club of Elefsina is Iraklis Eleusis, founded in 1928.

| Notable sport clubs based in Eleusis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Club | Sports | Founded | Achievements |

| Iraklis Elefsinas | Football | 1928 | Earlier presence in Gamma Ethniki |

| Panelefsiniakos | Football | 1931 | Earlier presence in A Ethniki |

| Basketball | 1969 | Earlier presence in A1 Ethniki | |

| O.K.E. | Basketball | 1996 | |

Notable people

edit- Aeschylus (c. 525 BC/524 BC – c. 456 BC/455 BC), playwright and veteran of the Battle of Marathon

- Theodoros Pangalos (1878–1952), general

- Stelios Kazantzidis (1931–2001), singer

- Vasilis Laskos (1899–1943), commander of submarine Katsonis, a hero of the Second World War

- Orestis Laskos (1908–1992), director, screenwriter and actor

- Vangelis Liapis (1914–2008), scholar and folklorist

- Theodoros Pangalos (1938– 2023), politician

- Alexandros Kontoulis (1858–1933), military officer

- Ioannis Kalitzakis (1966– ), footballer

- Katerina Mouriki (1951–), children's novelist

- Panagiotis Lafazanis (1951–), politician

Twin towns

editElefsina is twinned with:

Gallery

edit-

The upper part of one of the two caryatids that flanked the Lesser Propylaea of the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Eleusis.

-

Ruins of the Telesterion at the Sanctuary of Demeter in Eleusis with view to the modern town

-

Part of the ancient walls

-

Ruins of the East Triumphal Arch by Antoninus Pius, archaeological site

-

Cuirassed bust of Marcus Aurelius, archaeological site

-

Funerary Proto-Attic Amphora with a depiction of the blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseus and his companions, 670-660 BC, Eleusis Museum

-

Saint George's Cathedral

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Municipality of Elefsina, Municipal elections – October 2023, Ministry of Interior

- ^ "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2000) [1990]. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (new ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-582-36467-7.

- ^ Δήμητρος Ελευσινίας – Βικιθήκη [Orphic hymns / Demetrios Eleusinia]. el.wikisource.org (in Greek). Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ "Eleusis – Greek Mythology Link". www.maicar.com. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015.

- ^ Gardner, Ernest Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 262.

- ^ "Archaeologists Find a Classic Entrance to Hell". Adventure. 16 April 2013. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Homeric Hymn to Artemis 450

- ^ a b Pausanias (1918). "38.7". Description of Greece. Vol. 1. Translated by W. H. S. Jones; H. A. Ormerod. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Strabo. Geographica. Vol. ix. p.397. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- ^ a b Calasso, Roberto (2020). The celestial hunter. Richard Dixon. [London], UK. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-241-29674-5. OCLC 1114975938.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Vol. 2.15.

- ^ Pausanias (1918). "38.3". Description of Greece. Vol. 1. Translated by W. H. S. Jones; H. A. Ormerod. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Strabo. Geographica. Vol. ix. p.395. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- ^ Florin Curta; Andrew Holt (28 November 2016). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4.

- ^ Gisela M. A. Richter. “A Roman Copy of the Eleusinian Relief.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 30, no. 11, 1935, pp. 216–221. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3255443

- ^ Herodotus. Histories. Vol. 9.65.

- ^ Xenophon. Hellenica. Vol. 2.4.8, et seq., 2.4.43.

- ^ Demosthenes, c. Callicl. p. 1279.

- ^ Pausanias (1918). "38.6". Description of Greece. Vol. 1. Translated by W. H. S. Jones; H. A. Ormerod. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; William Heinemann – via Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Eusebius: Chronicle

- ^ Euseb. Chron. p. 81

- ^ a b Strabo. Geographica. Vol. ix. p. 395. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- ^ Plutarch Per. 13.

- ^ "History of the town of Eleusis". Archived from the original on 19 June 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Adamou E. & Drettas G. 2008, Slave, Le patrimoine plurilingue de la Grèce – Le nom des langues II, E. Adamou (éd.), BCILL 121, Leuven, Peeters, p.56.

- ^ "Museum of Greeks of Minor Asia".

- ^ Dahl, Roald (1986). Going Solo. Cape. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-224-02407-5.

- ^ Kassomenos, P. A.; Katsoulis, B. D. (31 July 2006). "Mesoscale and macroscale aspects of the morning Urban Heat Island around Athens, Greece". Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics. 94 (1–4): 209–218. Bibcode:2006MAP....94..209K. doi:10.1007/s00703-006-0191-x. ISSN 0177-7971. S2CID 119670327.

- ^ "June first ten days record". Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ "Monthly Bulletins". www.meteo.gr.

- ^ "Latest Conditions in Elefsina".

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization". Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "Climatological Information for Elefsina, Greece". Hellenic National Meteorological Service. 16 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "WMO Region VI (Europe, Continent only): Highest Temperature". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "eleusis 2021" (PDF). p. 16.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Eleusis". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

External links

edit- Official website (in English and Greek)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. VIII (9th ed.). 1878. p. 128.