Pro-Indonesia militias in East Timor, commonly known as Wanras (Indonesian: Perlawanan Rakyat), were active in the final years of the Indonesian occupation leading up to the 1999 independence referendum. They were groups of armed civilians trained by the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) to maintain peace and order in their region on official orders. The Indonesian Constitution of 1945 and the Defence Law of 1988 stipulate that civilians have the right and duty to defend the state by receiving basic military training.[1]

History

editDomingos Maria das Dores Soares, Administrator of Dili, created the Pam Swakarsa ("Self-Initiated Security Group") on 17 May 1999. The decision named José Abílio Osório Soares, Governor of Timor Timur, Lieutenant General Kiki Syahnakri, Provincial Military Commander (Danrem) and the Provincial Police Chief as the main advisors of Pam Swakarsa. Eurico Guterres was appointed Operational Commander. Among the 2650 registered members, there were 1521 members of the Aitarak militia.[2]

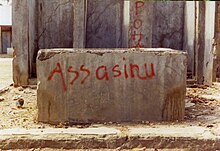

The existence of Wanra was confirmed by retired Lieutenant General Kiki Syahnakri in his testimony before the Truth and Friendship Commission (CTF) in October 2007.[3] Transmigration Minister Abdullah Mahmud Hendropriyono is considered responsible for the financing.[4] The CTF clarified the connections during the violent riots surrounding the independence referendum in East Timor in 1999. At that time, pro-Indonesian militias had tried to intimidate the population together with the TNI. These Pro-Indonesia militias were responsible for multiple atrocities and mass-killings during East Timor's bid for independence and transitional period. In Operation Guntur, up to 3,000 people were killed, hundreds of women and girls were raped, three quarters of East Timor's population were displaced and 75% of the country's infrastructure was destroyed. This led to the 1999 East Timorese crisis (known as the East Timor Scorched Earth campaign), which included notable incidents such as the Liquiçá Church, Manuel Carrascalão House, and Suai Church massacres. One of the most notorious militia leaders was Eurico Guterres, the leader of Aitarak, who was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison for his participation in the Liquiçá Church massacre.[5] Only the intervention of an international peacekeeping force was able to put a stop to the violence. Later on, East Timor came under the administration of the United Nations. According to the result of the referendum (78.5 % in favour of independence), East Timor became an independent state in 2002.

Syahnakri testified that the Wanra were legal civilian defence groups, which at the time were part of the general Indonesian defence system and existed everywhere in Indonesia, and therefore also in East Timor. However, these specified groups were only armed at their own request to protect their neighbourhood.[3]

A number of organisations founded in early 1999 formed the political arm of the pro-Indonesian autonomy movement. On 27 January 1999, sections of Wanras founded the Forum for Unity, Democracy and Justice (Indonesian: Forum Persatuan, Demokrasi dan Keadlian FPDK). Domingos Maria das Dores Soares, the government president (Bupati) of the district of Dili, took over the leadership. In April, the East Timor People's Front (Indonesian: Barisan Rakyat Timor Timur, BRTT) was also founded with Francisco Lopes da Cruz as its leader. The United Front for East Timor (UNIF), founded on 23 June as an umbrella organisation, brought together the FPDK, BRTT and other pro-Indonesian groups. The new organisation was under the joint leadership of Soares, Lopez da Cruz, and Armindo Soares Mariano, the chairman of the provincial parliament, also known as the People's Provincial Representative Council (DPRD). João da Costa Tavares commanded the militias of the UNIF, which united old militias and the newly founded ones from 1999 in the "Armed Forces of the Integration Struggle" (Indonesian: Pasukan Pro-Integrasi PPI).[6][7] The organisations were closely linked to the civil administration and were financed by it. They routinely attended military, police and government (Muspida) meetings, although they had no official status. An FPDK campaign vilified UNAMET, which was widely publicised in the Indonesian public and through diplomatic channels.[6]

After the independence referendum, the organisation was replaced by the University of Timor Aswain (UNTAS), which was founded in West Timor on 5 February 2000.[8]

Discussion about the use of the Wanra

editIndonesian military expert Kusnanto Anggoro from the Center for Strategic and International Studies emphasised that the Wanra should not be used for internal conflicts, but only to support the TNI in the fight against external threats. The defence law must clearly exclude the use of the Wanra in internal conflicts.

Yusron Ihza Mahendra, the deputy spokesman of Commission I for Defence of the House of Representatives, contradicts this opinion and also supports the use of the Wanra in internal conflicts.

Defence Ministry spokesman Brigadier General Edi Butar Butar explained that the current law does not even mention the terms "Wanra" and "Sishankamrata" (Indonesian: sistem pertahanan rakyat semesta; "defence of the population and security system"). The 2002 Defence Law only provides for the TNI as the main component of the defence system. Civilian groups are only listed as a reserve component. The continued existence of existing civilian units is now the responsibility of the provincial administration. The TNI is now only responsible for their military training.[1]

Militias

editNotable militias included:[5][9]

| Symbol | Wanra | District | Militia Chief |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aitarak (Thorn) | Dili | Eurico Guterres | |

| Besi Merah Putih (Red and White Iron) | Manuel de Sousa | ||

| Laksaur | Cova Lima | Olivio Mendonca Moruk | |

| Mati Hidup dengan Indonesia (Live and Die with Indonesia) | Ainaro | Cancio de Carvalho | |

| Team Alfa | Lautém | Joni Marques | |

| Saka/Sera | Baucau | Joanico da Costa | |

| Pedjuang 59-75 Makikit | Viqueque | Martinho Fernandes | |

| ABLAI | Manufahi | Nazario Corterel | |

| AHI | Aileu | Horacio | |

| Sakunar | Oe-Cusse Ambeno | Simão Lopes | |

| Halilintar | Bobonaro | Maliana: João da Costa Tavares;

Bobonaro: Natalino Monteiro | |

| Jati Merah Putih | Lautém (Lospalos) | Edmundo de Conceição Silva | |

| Darah Merah Integrasi | Ermera | Lafaek Saburai (Afonso Pinto), | |

| Naga Merah (Red Dragon) | Ermera | Miguel Soares Babo | |

| Dadarus Merah Putih | Bobonaro | Natalino Monteiro |

Fictional depictions

editFictional representations of these groups, their members, and their atrocities were shown in the 2006 Australian miniseries Answered by Fire.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Nurhayati, Desy (2016-01-07). "TNI 'should not deploy Wanra' for internal rows". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2024-06-19 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Comissão de Acolhimento, Verdade, e Reconciliac̦ão Timor Leste (2013). "Part 3: The History of the Conflict". Chega!: The Final Report of the Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR) (PDF). KPG. p. 138. ISBN 978-979-9106-47-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nurhayati, Desy (2015-04-30). "TNI 'armed' East Timor civilians". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2024-06-19 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "Timorese slam award for 'rights abuser' ex-general". UCA News. 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b Robinson, Geoffrey (2001). "People's war: militias in East Timor and Indonesia" (PDF). South East Asia Research. 9 (3): 271–318. doi:10.5367/000000001101297414. S2CID 29365341.

- ^ a b Comissão de Acolhimento, Verdade, e Reconciliac̦ão Timor Leste (2013). "The campaign – Active pro-autonomy groups". Chega!: The Final Report of the Timor-Leste Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR). KPG. pp. 140‒141. ISBN 978-979-9106-47-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Domingos Soares - Master of Terror". 2010-10-09. Archived from the original on 2010-10-09. Retrieved 2024-06-19.

- ^ Müller, Michaela; Schlicher, Monika (2002). "Politische Parteien und Gruppierungen in Ost-Timor, Indonesien-Information Nr. 1 2002 (Ost-Timor)". Watch Indonesia!.

- ^ "Action in Solidarity with Asia and the Pacific". 1999. Archived from the original on 2005-05-08. Retrieved 2024-06-19.