Drigung Thil Monastery (Wylie: bri gung mthil 'og min byang chub gling) is a monastery in Maizhokunggar County, Lhasa, Tibet founded in 1179. Traditionally it has been the main seat of the Drikung Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. In its early years the monastery played an important role in both religion and politics, but it was destroyed in 1290 by Mongol troops under the direction of a rival sect. The monastery was rebuilt and regained some of its former strength, but was primarily a center of meditative studies. The monastery was destroyed after 1959, but has since been partly rebuilt. As of 2015 there were about 250 resident monks.

| Drigung Thil Monastery | |

|---|---|

Tibetan transcription(s) Tibetan: འབྲི་གུང་མཐིལ Wylie transliteration: 'bri gung mthil 'og min byang chub gling THL: Drigung Til Okmin Jangchup ling Chinese transcription(s) Simplified: 直贡梯寺 | |

Drigung Thil Monastery | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Tibetan Buddhism |

| Sect | Kagyu (Drikung Kagyu lineage) |

| Location | |

| Location | Mamba Township, Maizhokunggar County, Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China[1] |

| Country | China |

| Geographic coordinates | 30°6′23.4″N 92°12′14.7594″E / 30.106500°N 92.204099833°E |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | Drigung Kyobpa Jigten-gonpo-rinchenpel |

| Date established | 1179 |

Location

editThe monastery is located in the Drikung region of central Tibet.[2] It is on the south slope of a long mountain ridge about 120 kilometres (75 mi) north-east of Lhasa, and looks over the Shorong valley.[3][4] It is at an elevation of 4,465 metres (14,649 ft), about 180 metres (590 ft) above the valley floor.[5] It commands a panoramic view of the valley.[6] Drigung Thil is in Nita township, 61 kilometres (38 mi) from the county seat, which in turn is 73 kilometres (45 mi) from Lhasa, the regional capital.[4] Three other monasteries of the Drikung Kagyu sect are located in the same region, Yangrigar, Drikung Dzong, and Drikung Tse.

Name

editAccording to legend the founder, Jigten Sumgön, chose the site when he was following a female yak (dri) who lay down at this spot. The monastery and the region are said to be named after the yak, and the monastery has preserved the horns of the yak. A more plausible source says that the region was the fiefdom of Dri Seru Gungton, a minister of King Songtsän Gampo, and is named after him.[2]

History

editDrigung Thil Monastery was founded in 1179 by Jigten Sumgön (1143–1217), the founder of the Drikung Kagyu tradition. The order is one of the eight minor Dagpo Kagyu lineages derived from disciples of Phagmo Drupa Dorje Gyalpo (1110–70), who was in turn a disciple of Gampopa.[7] The monastery was located beside a hermitage erected in 1167 by Minyak Gomring, an illiterate ascetic pupil of Phagmodrupa.[3] The population has fluctuated over the years.[7]

The abbot was the religious head, but the secular ruler was a Gompa or Gomchen. With rare exceptions this was a hereditary position within the Kyura clan until the 16th century.[3] In the early years after the death of Jigten Sumgön the monastery grew quickly, rivaling the Sakya sect in political and religious influence. The monastery dispatched lamas across Tibet in the 13th century to found meditation colonies at pilgrimage sites including Mount Kailash, the Lapchi caves and the sacred Tsari Mountain.[8]

In 1240 the Mongol armies under Dorta Nagpo (Dorta the Black) sacked Gyel Lhakhang Monastery and Reting Monastery, then turned on Drigung. The monks managed to defend the monastery and prevent its destruction.[8] In 1290, in order to destroy the political influence of Drigung, a Mongol army under the Sakya general Aklen destroyed the monastery.[8] The 9th lineage holder, Chunyi Dorje Rinchen (1278-1314) rebuilt the monastery with the help of the Sakya and the Emperor.[3] The role of the monastery was now mainly limited to being a center for contemplative studies and serving as the home of the Drigung Kargyupa subsect.[8] The monastery had regained some of its strength by the mid-14th century, but after the 15th century was eclipsed by the rise of the Gelug sect.[4] Throughout the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) the monastery played an important role in Sino-Tibetan relations.[3]

The monastery has a strong tradition of meditation, with meditators living and practicing intensively in nearby caves. Jigten Sumgön started a tradition of giving courses on sutra and tantra subjects twice yearly, which was followed by his successors, but the monastery does not have a strong tradition of scholarship. Until the 19th century the emphasis was on faith and ritual. The 34th abbot, Kyabjey Zhiway-lodro, established a teaching college at the monastery. The monks would each spend five years at this college using logic and debate to study thirteen scriptural texts.[7]

In 1959 there were about four hundred monks, sixty people in meditation retreats and eight Incarnate Lamas.[7] Before and during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) the monastery was looted of almost all its collection of statues, stupas, thangkas, manuscripts and other objects apart from a few small statues that the monks managed to hide. The buildings were severely damaged. Reconstruction began in 1983 and seven of the fifteen temples were rebuilt.[3] The traditions of the monastery were also revived in 1989 at the Jangchubling Drikung Kagyu Institute in Dehradun, Uttar Pradesh (now Uttarakhand), India.[7] As of 2015 Drigung Thil Monastery was occupied by about 250 monks. Although well known, particularly for its sky burial site, it does not attract many tourists, especially since the monks moved to close sky burials to uninvited guests.[9] Nevertheless, in the Tibetan New Year it is visited by thousands of pilgrims, mainly coming from Kham to the east.[6]

-

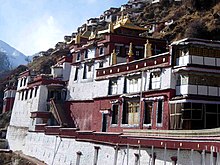

Monastery complex in 2009

-

Monastery complex

Structures

editThere are more than fifty buildings in the monastic complex.[6] The Tsuglakhang, the main shrine hall, stands on a rampart of solid stone about 20 metres (66 ft) high, fronted by a large terrace that in the past was the place where lessons were given. The shrine room in this building holds many statues and stupas, including a central statue of Jigten Sumgön made of gold and copper and filled with rare jewels and relics.[3] The image of Jigten Sumgön stands beside a large figure of the Guru Rimpoche, and a chörten in the hall holds Jigten Sumgön's remains.[8]

There are many smaller buildings scattered around the ridge. They are accessed by steep steps, or by wooden ladders in a few cases.[3] There are several temples above the main chanting hall, which almost all contain a statue of Jigten Sumgön. A small building above the tsokchen (assembly hall) is dedicated to Achi, who protects the monastery, with depictions of her peaceful and wrathful manifestations. A pilgrimage trail runs around the monastery from below the chanting hall up to the crest of the ridge and the sky burial site at 14,975 feet (4,564 m), and then skirts various chörtens and shrines before descending to the starting point. The monastery has a guest house and a tea shop.[8]

-

Outlook over the valley

-

Monk tending fire

-

Lamps

-

Monks and drums

References

edit- ^ Drikung Thil monastery, (near) Poindo/Lhunzhub.

- ^ a b Drikung, The Main Seat of Drikung Kagyu Order.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Drikung Thil, Drikung Kagyu Order.

- ^ a b c Zhang Hongxia 2008.

- ^ McCue 2010, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Drigung Monastery, The Land Of Snows.

- ^ a b c d e Berzin 1991.

- ^ a b c d e f McCue 2010, p. 129.

- ^ Logan, Pamela. "Survival and Evolution of Sky Burial Practices". Retrieved 28 July 2024.

Sources

edit- Berzin, Alexander (1991). "A Brief History of Drigungtil Monastery". Kagyü Monasteries. Dharamsala, India: Chö-Yang, Year of Tibet. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- "Drigung Monastery". The Land Of Snows. 2010-09-30. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Drikung, The Main Seat of Drikung Kagyu Order". Drikung Kagyu Order of Tibetan Buddhism. Archived from the original on 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Drikung Thil". Drikung Kagyu Order of Tibetan Buddhism. Archived from the original on 2015-02-03. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "Drikung Thil monastery, (near) Poindo/Lhunzhub, Xizang, CN". Mapping Buddhist Monasteries. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- McCue, Gary (2010). Trekking in Tibet: A Traveler's Guide. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1-59485-411-8. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- Zhang Hongxia (2008-10-18). "Kagyu monasteries - Drigung Thil Monastery" (in Chinese). Xinhua News Network Center. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

Literature

edit- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2001. Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet. Vol. One: India & Nepal; Vol. Two: Tibet & China. (Volume One: 655 pages with 766 illustrations; Volume Two: 675 pages with 987 illustrations). Hong Kong: Visual Dharma Publications, Ltd. ISBN 962-7049-07-7. ’Bri gung mthil («drigung til») monastery: gSer khang lha khang («serkhang lhakhang»); Pls. 171B, 172B, 212C, 255B, 256B, 256C, 256D–E, 258B, 264C, 275B–C, 275E, 277C, 288C, 324F, 329D; Tshogs chen («tsokchen»); Pls. 260E, 261A, 269A–B, 329B–C; Ya phyi lha khang («yachi lhakhang»), Pl. 13.

External links

edit- Drigungtil high resolution photographs

- Brief history of monastery

- Drigung Monastery travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Media related to Drigung Monastery at Wikimedia Commons