Total Recall is a 1990 American science fiction action film directed by Paul Verhoeven, with a screenplay by Ronald Shusett, Dan O'Bannon, and Gary Goldman. The film stars Arnold Schwarzenegger, Rachel Ticotin, Sharon Stone, Ronny Cox, and Michael Ironside. Based on the 1966 short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" by Philip K. Dick, Total Recall tells the story of Douglas Quaid (Schwarzenegger), a construction worker who receives an implanted memory of a fantastical adventure on Mars. He subsequently finds his adventure occurring in reality as agents of a shadow organization try to prevent him from recovering memories of his past as a Martian secret agent aiming to stop the tyrannical regime of Martian dictator Vilos Cohaagen (Cox).

| Total Recall | |

|---|---|

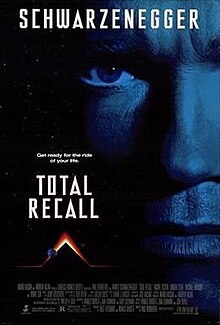

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Verhoeven |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by |

|

| Based on | "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" by Philip K. Dick |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jost Vacano |

| Edited by | Frank J. Urioste |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Tri-Star Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $48–80 million |

| Box office | $261.4 million |

Shusett bought the rights to Dick's short story in 1974 and developed a script with O'Bannon. Although considered promising, the ambitious scope kept the project in development hell at multiple studios over sixteen years, seeing forty script drafts, seven different directors, and multiple actors cast as Quaid. Total Recall eventually entered the early stages of filming in 1987 under the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group shortly before its bankruptcy. Schwarzenegger, who had long held an interest in the project but had been dismissed as inappropriate for the lead role, convinced Carolco Pictures to purchase the rights and develop the film with him as the star. On an estimated $48–80 million budget (making it one of the most expensive films made in its time), filming took place on expansive sets at Estudios Churubusco in Mexico over six months. Cast and crew experienced numerous injuries and illnesses during filming.

Total Recall was anticipated to be one of the year's most successful films. On its release, the film earned approximately $261.4 million worldwide, making it the fifth-highest-grossing film of the year. Its critical reception was mixed, with reviewers praising its themes of identity and questioning reality, but criticizing content perceived as vulgar and violent. The practical special effects were well received, earning the film an Academy Award, and the score by Jerry Goldsmith has been praised as one of his best works.

Since its release, Total Recall has been praised for its ambiguous ending positing whether Quaid's adventures are real or a fantasy, and it has also been analyzed for themes of authoritarianism and colonialism. Retrospective reviews have called it one of Schwarzenegger's best films and placed it among the best science fiction films ever made. Alongside comic books and video games, Total Recall has been adapted into the 1999 television series Total Recall 2070. An early attempt at a sequel, based on Dick's The Minority Report, became the 2002 standalone film Minority Report, and a 2012 remake, also titled Total Recall, failed to replicate the success of the original.

Plot

editIn 2084, Mars is a colonized world under the tyrannical regime of Vilos Cohaagen, who controls the mining of valuable turbinium ore. On Earth, construction worker Douglas Quaid experiences recurring dreams about Mars and a mysterious woman. Intrigued, he visits Rekall, a company that implants realistic false memories, and chooses one set on Mars (with a blue sky) where he is a Martian secret agent. However, before the implant is completed Quaid lashes out, already thinking he is a secret agent. Believing Cohaagen's "Agency" has suppressed Quaid's memories, the Rekall employees erase evidence of Quaid's visit and send him home.

En route, Quaid is attacked by men led by his colleague Harry because Quaid unknowingly revealed his past; Quaid's instincts take over and he kills his assailants. At home, he is assaulted by his wife Lori, who claims she was assigned to monitor Quaid by the Agency and that their marriage is a false memory implant. He flees but is pursued by armed men led by Richter, Cohaagen's operative and Lori's real husband. A man who claims to be Quaid's former acquaintance gives him a suitcase containing supplies and a video recording in which Quaid identifies himself as Hauser, a Cohaagen ally who defected after falling in love. According to the recording, Cohaagen brainwashed Hauser to become Quaid and conceal his secrets before securing him on Earth. Hauser instructs Quaid to return to Mars and stop Cohaagen.

On Mars, Quaid evades Richter and, following a note from Hauser, travels to Venusville, a district populated by humans and those mutated by air pollution and solar radiation within the cheaply built domes protecting the colony. Quaid meets Melina, the woman from his dreams, who knows him as Hauser and believes he is still working for Cohaagen. In his hotel room, Quaid is confronted by Lori and Dr. Edgemar from Rekall, who explains that Quaid is still at Rekall on Earth, trapped in his fantasy memory and on the verge of permanent brain damage. Quaid notices Edgemar is sweating and, believing he is real, kills him. Quaid is captured by Richter's men, but Melina rescues him and Quaid kills Lori. The pair escape with taxi driver Benny to Venusville.

The mutants lead them to a hidden rebel base, where Quaid meets their leader Kuato, a mutant growing out of the abdomen of his brother George. Kuato psychically reads Quaid's mind, learning that Cohaagen is hiding a 500,000-year-old alien reactor built into a mountain that, once activated, produces breathable air but could also destroy all turbinium, ending Cohaagen's monopoly over both resources. Benny shoots George, revealing himself to be in Cohaagen's employ, and Cohaagen's forces attack the base, killing the rebels. Kuato implores Quaid to start the reactor before Richter executes him. Cohaagen disables Venusville's air supply to slowly suffocate the remaining inhabitants.

Quaid and Melina are brought to Cohaagen, who explains that Hauser was his close friend who volunteered to become Quaid as an elaborate ruse to bypass the mutants' psychic abilities, infiltrate the rebellion, and destroy it. Quaid's Rekall visit had activated him earlier than planned and Cohaagen has been helping him to survive the oblivious Richter's pursuit. Cohaagen orders Hauser's memories to be restored in Quaid and Melina to be reprogrammed as his subservient lover, but they manage to escape to the mines below the reactor. Benny, Richter, and his men attack them, but the pair outwits and kills them all.

Cohaagen awaits them in the reactor control room, claiming that activating it will destroy the planet. He activates an explosive to destroy the controls, but Quaid throws the explosive into a nearby tunnel, where it detonates and creates a breach to the Martian surface. The explosive decompression blows Cohaagen out to the surface where he suffocates and dies. Quaid activates the reactor before he and Melina are also blown out. The reactor melts the planet's ice core into gas that bursts to the surface, forming a breathable atmosphere and saving Quaid, Melina, and the rest of Mars's population. As everyone beholds the now-blue sky, Quaid momentarily wonders if everything was a dream, before he and Melina kiss.

Cast

edit- Arnold Schwarzenegger as Douglas Quaid / Carl Hauser: An Earth-based construction worker with a hidden past[1]

- Rachel Ticotin as Melina: A Martian freedom fighter[2]

- Sharon Stone as Lori: Quaid's wife, revealed to be a secret agent[1]

- Ronny Cox as Vilos Cohaagen: The governor of the Martian colony[3]

- Michael Ironside as Richter: Cohaagen's ruthless enforcer[3][4]

- Marshall Bell as George / Kuato (voice): The mutant leader of the Martian resistance[5]

- Michael Champion as Helm: Richter's right-hand man[6]

- Mel Johnson Jr. as Benny: A Martian taxi driver[7]

- Roy Brocksmith as Dr. Edgemar: A Rekall employee[1]

- Rosemary Dunsmore as Dr. Renata Lull: A Rekall programmer[8]

The Earth-based cast features Ray Baker as Rekall salesman Bob McClane,[8] Robert Costanzo as Harry, and Alexia Robinson as Tiffany.[9] Robert Picardo provides the voice and visual likeness of Johnnycab, an automated taxi driver.[10]

The Martian cast includes Lycia Naff as Mary, a mutant three-breasted prostitute,[11] Marc Alaimo as Captain Everett, Dean Norris as Tony, Debbie Lee Carrington as Thumbelina, Sasha Rionda as Mutant Child, Mickey Jones as Burly Miner, and Priscilla Allen as "Fat lady".[9]

Production

editEarly development

editThe development of Total Recall began in 1974, when producer Ronald Shusett purchased the adaptation rights to science fiction writer Philip K. Dick's 1966 short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" for $1,000.[a] Shusett had read the 23-page story by the then-little-known pulp fiction writer in an April 1966 edition of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.[12] Dick's story depicts a meek clerk on Earth named Quail who visits Rekal Incorporated to receive a memory implant of being a secret agent on Mars. However, the process uncovers his true identity as a secret agent who previously visited Mars and whose death will bring about an alien invasion.[15][16]

Renaming it Total Recall, Shusett worked with Dan O'Bannon to write the script. O'Bannon exhausted the existing material quickly, and the short story's abrupt ending meant he could only write thirty pages, effectively only the first act, and an original second and third act were needed; he suggested sending Quaid to Mars.[15] Shusett and O'Bannon disagreed over the third act, the former wanting something more dramatic. O'Bannon's ending revealed the handprint on the alien machine as Quaid's, who is a replica of the original, and placing his hand on it grants him total memory recall. O'Bannon described the filmed ending as "lame".[17][18] Dick read the script prior to his death in 1982 and, according to O'Bannon, enjoyed it.[19] Although studios deemed Shusett and O'Bannon's script an ambitious and brilliant idea, it was essentially considered unfilmable, in part because of the extensive special effects and high budget that would be required.[13][14]

The pair moved on to collaborating on the script for the science fiction horror film Alien (1979), the success of which earned Shusett a development deal at Walt Disney Studios. He pursued the Total Recall project at the studio, initially budgeted at $20 million, but the idea did not progress because issues with the third act could not be resolved. The project was sold to Dino De Laurentiis's De Laurentiis Entertainment Group (DEG) in 1982.[b]

Development under De Laurentiis Entertainment Group

editDe Laurentiis considered Richard Rush, Lewis Teague, Russell Mulcahy, and Fred Schepisi to direct the film, before choosing David Cronenberg in 1984.[17][21] Cronenberg was unfamiliar with Dick's work but was interested in the script. Even so, problems remained with the third act and Cronenberg spent the next year writing twelve separate drafts.[17][22] In his finished script, Quaid's true identity is Chairman Mandrell, the dictator of Earth who, following a failed assassination attempt on his life, is convinced by Mars Administrator Cohaagen to confront the organization that suppressed his memory. Cohaagen later reveals that Quaid is an inconsequential government worker chosen to play the role of Mandrell to facilitate Cohaagen usurping control of the Earth. Quaid defeats Cohaagen and assumes the identity of Mandrell.[23] Cronenberg was responsible for the mutant characters, including Kuato (originally called Quato), and further developed an idea by Shusett about mutant animals, known as Ganzibulls, in the Martian sewers; Cronenberg made them mutant camels.[24]

Cronenberg found himself at odds with Shusett regarding the tone, as Shusett and De Laurentiis did not want it to be as serious as the science fiction film Blade Runner (1982)—an adaptation of Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968).[25] Shusett described Cronenberg's work as bringing the film back to Dick's original short story, whereas they wanted an adventure closer to "Raiders of the Lost Ark go to Mars".[13][16][26] Cronenberg did not want to make that film and chose to quit. He was also frustrated by his disagreements with Shusett and De Laurentiis, and the casting of Richard Dreyfuss in the lead role.[25] Dreyfuss had requested further rewrites to have Quaid reflect the everyman persona he had established in his previous films, rather than the action-focus of the Shusett/O'Bannon story. Cronenberg had wanted to cast William Hurt as the lead instead and focus more on the concepts of memory and identity.[13][27] Christopher Reeve, Jeff Bridges, and Harrison Ford were also considered for Quaid.[c] De Laurentiis threatened to sue Cronenberg for quitting but was placated by Cronenberg agreeing to work with him on a different film.[25] A few years later, De Laurentiis offered Cronenberg the opportunity to make Total Recall as he had wanted, but Cronenberg was not interested and did not want to argue with Shusett again.[25]

De Laurentiis sought to keep the budget low following the financial failure of Dune (1984), and wanted to reduce costs by eliminating Mars entirely, but Shusett and O'Bannon dissented.[21][30] Problems with finalizing the script and the high budget continued to stall Total Recall for the next few years.[13][21] In 1987, De Laurentiis again considered hiring Rush as director, but De Laurentiis disliked the finale featuring a breathable atmosphere on Mars while Rush supported the idea. De Laurentiis accepted he was wrong after hiring director Bruce Beresford, who also supported the ending.[31] Around this time, writer Gary Goldman was offered an opportunity to refine the script, but he turned it down to focus on his own project, called Warrior, that he was working on alongside director Paul Verhoeven at Warner Bros. Pictures.[31] Beresford began preparations for a version of Total Recall described by Shusett as less gritty and more "Spielbergian" in tone, and Patrick Swayze was cast as Quaid. Set construction was underway in Australia when DEG filed for bankruptcy in 1988.[16][31][32] Approximately 80 crew were fired and the sets had to be destroyed.[31] By this point, the project had already accrued $8 million in pre-production costs, and $6 million in turnaround costs—a process allowing other studios to purchase the idea.[19][20][33]

Development under Carolco Pictures

editArnold Schwarzenegger became aware of Total Recall in the mid-1980s, either during filming of Commando (1985) or Raw Deal (1986).[13][34] He liked the script and agreed to pursue it alongside producer Joel Silver while filming Predator (1987), but the project remained unrealized due to its prohibitive budget and because De Laurentiis did not think Schwarzenegger was right for the lead role.[14][16] Following DEG's bankruptcy, Schwarzenegger convinced Andrew G. Vajna and Mario Kassar, co-owners of the independent film studio Carolco Pictures, with whom he had made Red Heat (1988), to purchase the rights for $3 million, including pre-production costs.[35] Schwarzenegger wanted to star in the film, pending rewrites to his satisfaction, and his fame and international appeal justified the studio investing the necessary budget.[16][33][34] Carolco completed its acquisition of the majority of DEG's business and assets in April 1989.[36] Schwarzenegger was given substantial influence over the project: he retained Shusett as a screenwriter and co-producer alongside producer Buzz Feitshans, and oversaw script revisions, casting decisions, and set construction.[d] He described himself as effectively an executive producer without the responsibility, but he involved himself heavily because he wanted the project to work.[37] He received a $10–$11 million salary, plus 15% of the film's profits.[40][41][e]

Schwarzenegger hired Verhoeven as the director after being impressed by his science fiction film RoboCop (1987), for which Schwarzenegger had been considered in the lead role.[34][35] Verhoeven had previously been courted by Shusett to direct the film based on his work on Soldier of Orange (1977), but declined then because he did not like science fiction.[35] Even so, Verhoeven accepted Schwarzenegger's offer after reading the Mars hotel scene where Dr. Edgemar attempts to convince Quaid he is still on Earth.[35] Verhoeven had wanted to avoid special effects-heavy films after RoboCop and said that he did not realize how much effects work would be involved.[34] He requested Goldman be brought in to help with rewrites, as well as some core personnel from RoboCop, including cinematographer Jost Vacano, production designer William Sandell, and special effects artist Rob Bottin.[42][43] By this point, approximately thirty drafts had been completed, credited to a combination of Shusett and either O'Bannon, Jon Povill, or Steven Pressfield, among others. Verhoeven read each one and highlighted those he wanted Goldman to reference.[43]

Writing

editGoldman had little knowledge of Dick's work but tried to respect the source material and work of previous screenwriters.[44] He considered the second half of the film a concession to traditional Hollywood narratives and so retained most of the structure from Beresford's shooting script. Because the creative team wanted to commence soon, Goldman believed he did not have the freedom to make substantial changes to the script and focused on refining the existing content and making the scientific aspects more realistic. Verhoeven and Schwarzenegger agreed that everything after Dr. Edgemar's visit to Quaid on Mars was not working.[43][45] Verhoeven wanted a significant change, to indicate that Edgemar could be telling the truth and Quaid is actually having a mental breakdown on Earth. Goldman rewrote the script to make it possible for the film to be viewed as both reality and fantasy.[46] He also made Hauser an ally to Cohaagen, clearly defining Quaid and Hauser as separate identities.[47] Goldman believed that making Hauser evil would better justify Quaid not returning to his original personality. It would also explain why Hauser becomes Quaid: to conceal his intentions from the psychic mutants. Goldman made the Benny character a villain, because he believed African Americans were typically typecast as good characters and the reveal would be surprising.[48]

The script also had to be revised to match Schwarzenegger's action-hero public image, although Goldman tried to make it less comical than some of the actor's previous films.[45] The meek clerk Quail was renamed Quaid, to avoid referencing then-vice president Dan Quayle, and became a muscle-bound construction worker, while fight scenes were rewritten to include more feats of strength and less martial arts or running.[15][16][37] Second unit director and stunt coordinator Vic Armstrong, among other stunt people who had worked with Schwarzenegger on Conan the Barbarian (1982) and Red Sonja (1985), said that they knew what he could physically do without looking silly.[49] Schwarzenegger also wanted more creative methods to dispatch Quaid's foes because he had been criticized for an over-reliance on guns to kill people in films like Commando.[50] After Goldman's first rewrite, he discussed it with Verhoeven, Schwarzenegger, Shusett, Vajna, and Kassar. Schwarzenegger and Shusett believed the climax lacked emotion, which was an intentional choice by Verhoeven, who did not take the Martian rebel plot very seriously and prioritized the intellectual aspects of the narrative. To appease Schwarzenegger, Goldman conceived of Cohaagen shutting off the oxygen to the mutants in Venusville.[45] After nearly sixteen years in development, seven directors, four co-writers, and forty script drafts, Total Recall went into production.[13][51][52]

Cast and characters

editVerhoeven chose Michael Ironside to portray Cohaagen's henchman Richter. Ironside had previously auditioned for the lead in RoboCop and Verhoeven had also offered him the role of antagonist Clarence Boddicker, which he turned down because he did not want to portray another "psychopath" character following his role in Extreme Prejudice (1987). Ironside said he considered Richter more of a "sociopath", who had personal ambitions and covets Cohaagen's position.[3][50][53] Turning down a role on RoboCop and a separate film had created the impression that Ironside was difficult to work with, so he had to complete an audition before being offered the role. In it, he portrayed someone having an emotional breakdown leading to him lying on the floor crying as Verhoeven moved in for a closeup shot.[3][54] Schwarzenegger believed Ironside's physical presence made him a credible threat to his portrayal of Quaid.[50]

The female leads, Rachel Ticotin and Sharon Stone, were chosen in part for their athleticism, which was needed for the physically demanding roles.[13] Stone said that her physically formidable character resulted in the cast and crew treating her like she was "one of the guys", and that Ironside "was the one guy who never forgot I was a woman. When I was thrown down, he would help me up."[55] Verhoeven's daughters were responsible for casting Benny, picking Mel Johnson Jr.'s screen test for the available options. He recounted having just finished filming a "horrible" black exploitation film when he read the Total Recall script and, after seeing Benny described as a "black jivester", he threw the script across the room. Nonetheless, he eventually read it through and decided to audition because he believed the character was more fully realized, saying "this guy is cold and calculating and the story was intriguing."[7][10][56]

Cox had previously worked with Verhoeven on RoboCop and traded on the actor's history of playing good-natured characters to make his villainous turn more impactful. Describing his portrayal, Cox said that he did not employ method acting but did try to understand how the character would feel and think and how he would react to situations and that would determine his performance. The character's hairstyle came about after Cox's hair was slicked-back in order to make a face mold for special effects purposes. Cox knew it was the right look and convinced Verhoeven to reshoot two days of Cox's scenes with the new style.[10][57] When Marshall Bell auditioned for the role, the script did not explain the relationship between George and Kuato, and he was confused as to why George had so few lines. Although voice actors were considered for Kuato, Verhoeven decided to use Bell.[5] Verhoeven based the appearance and physicality of Brocksmith's Dr. Edgemar on the central scientist character portrayed by Paul Newman in Alfred Hitchcock's 1966 thriller Torn Curtain. He wanted an actor who looked "naive and strange and a bit weird."[58]

Filming and post-production

editPrincipal photography for Total Recall began in April–May 1989.[28][59] Filmed almost entirely in sequence—a rare feat—the production took place over 20 weeks.[f] The initial budget was reported as $30 million,[20] but the final budget was reported as being between $48 million and $80 million.[g][h] Total Recall was filmed almost entirely on sets at Estudios Churubusco in Mexico City, Mexico, where 43 cast and up to 500 crew members worked across forty-five sets on ten soundstages. The Earth train station was filmed in the Mexico City Metro and many exterior Mars scenes took place at the Valley of Fire State Park in Overton, Nevada.[i]

Shusett and Goldman were present on set, providing additional rewrites where necessary; Goldman estimated the script was changed "less than one percent".[68] Verhoeven sometimes required up to twenty takes of scenes, but remained faithful to the script and discouraged improvisation. Even so, some scenes, such as Benny's death, lacked sufficient detail and in these cases dialogue was mostly improvised.[7][32][68] Although Verhoeven had been adamant that he did not want a second unit director—having fired three of them on RoboCop—Armstrong ended up filming 1,200 different setups and all of the fight scenes; Verhoeven was happy with his work. Armstrong's first scene was filming Schwarzenegger drilling cement.[60]

Filming was beset by injuries and illness. Almost everyone involved suffered from dust inhalation on set. Food poisoning and gastroenteritis from the local Mexican cuisine was also a problem, except for Shusett and Schwarzenegger, who had his food brought from the United States after a negative experience while filming Predator in Mexico.[18][32] The illness compounded the difficulties Lycia Naff had filming her scenes as the three-breasted prostitute. She said she felt like crying because even though the breasts were artificial, she felt exposed in front of the cast and crew.[11] Schwarzenegger cut his wrist while smashing a train window when an explosive designed to pre-detonate the glass failed. His injuries were patched up and concealed by his jacket. He also incurred other minor cuts and broken fingers.[32][55]

Ironside cracked his sternum and separated two ribs after running into Michael Champion, who was holding an Uzi during the pursuit of Quaid and Melina in a Martian hotel. Filming had to be paused while he recovered, as Richter was involved in most of the remaining scenes. After three weeks, a producer asked that he return to filming but they could not obtain insurance unless Ironside performed fifty push-ups. Despite the doctor's advice, he attempted the feat and reinjured himself; after thirty push-ups, the doctor said it was sufficient. Ironside's first scene upon his return involved him fighting Schwarzenegger on an elevator, but he struggled to lift his arm. The doctor had Oakland Raiders quarterback Jim Plunkett drop off a brace built for his own injury, which held Ironside's chest in a stable position, although it made breathing difficult. Ironside filmed his scene over the remainder of the day, only being hit once accidentally by Schwarzenegger, who was cautious due to his condition.[3] A separate fight between Stone and Ticotin was arranged to feature one of the actresses and one stunt person because padding could not be concealed under their outfits. Verhoeven wanted the actresses to perform the fight stunts themselves, but Armstrong insisted on using a stunt person.[60]

Schwarzenegger was known for his pranks on the set, such as arranging styrofoam snowball fights and water pistol battles during dinners as well as booking parties to reward the crew for the six-day working weeks and practical stunts.[7][32][38] Even so, Ironside recounted how Schwarzenegger helped him stay in regular contact with his ill sister using the personal phone in his trailer, at a time before widespread use of mobile phones or internet access. Ironside later learned Schwarzenegger was also regularly calling his sister to check on her.[3]

Initially scheduled for release on June 15, Total Recall's post-production schedule was rushed to move the date forward two weeks to avoid competition from other films, particularly Dick Tracy with its cast of popular stars. Editor Frank J. Urioste worked overtime to complete Total Recall's 113-minute cut early.[39][68][69] This meant there was no time to test screen the film, which Verhoeven and Goldman believed worked against the finished product, including its third act.[39][68] The film also had to be trimmed to remove violent content and gore, including a longer version of Benny's death, to avoid an X rating, which would have restricted attendance to audience members over the age of 17. Total Recall ultimately received an R rating, allowing younger people to see it when accompanied by an adult.[18][70]

Special effects and design

editThe development of the film's special effects was led by Dream Quest Images, with Eric Brevig serving as visual effects supervisor, Alex Funke as special effects photographer, Thomas L. Fisher as special effects supervisor, William Sandell as production designer,[j] and Mary Siceloff as effects producer.[42] Rob Bottin, who previously worked with Verhoeven on RoboCop, provided the character visual effects.[3][5] Concept artist Ron Cobb and illustrator Ron Miller contributed to designs for technology, vehicles, and locations.[21][74][75] Additional effects were provided by Metrolight Studios,[72] and Industrial Light & Magic.[39]

Total Recall features over 100 visual effects, including miniatures and bluescreen effects.[42] The film was made at the onset of computer-generated imagery (CGI), which was not a suitable option for photorealistic or textured imagery, and was used mainly in the X-ray machine sequence. Most other effects were practical, employing sophisticated prosthetics and animatronics to realize automated taxi drivers, "fat lady" disguises, mutants, and scenes of explosive decompression.[5][73][76] Total Recall features thirty-five sets across eight of Estudios Churubusco's soundstages.[71] The sets were expansive and connected by tunnels so long that they continued outside of the stage, making it possible to drive between them on film.[10][53][54]

Expansive locations, including Martian exteriors, were created using miniature sets produced by Stetson Visual Services in Los Angeles, and supervised by Mark Stetson and Robert Spurlock.[77] The sets were large, with the alien reactor being among the largest and most complex sets ever constructed in cinema, and the largest set built for the film. It had to be built vertically to fit on Dream Quest's stage. Even so, it was limited by the 25 ft (7.6 m) high ceilings.[78][79] The Martian mountain set was also substantial, measuring 14 ft (4.3 m) tall and 14 ft (4.3 m) in diameter, with only the frontside constructed, allowing special effects to be operated from behind.[80][81]

Music

editThe score was composed by Jerry Goldsmith. The producers intended to have him record the score in Munich because the pay for musicians there was lower, but the players were unfamiliar with Goldsmith's style and the resulting score was disappointing. Instead, Goldsmith was given the funding necessary to record the score in London with the National Philharmonic Orchestra, who were more fitting to Goldsmith's musical intentions with brass and string instruments combined with electronic sounds. The recording was put on hiatus for three months so Verhoeven could have time to edit the special effects, during which Goldsmith recorded the score for Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990), before returning to finish his work on Total Recall. Goldsmith also performed the commercial jingles and elevator music heard in the film, and composer Bruno Louchouarn provided additional pieces heard on Mars.[84]

Release

editContext

editFollowing the previous year's record $5 billion box office, more films than ever were expected to surpass $100 million at box office as fifty films were scheduled for release during the summer theater season of 1990 (May 18 – September 3). Dick Tracy was predicted to dominate the box office, and films such as Another 48 Hrs., Back to the Future Part III, Days of Thunder, Die Hard 2, RoboCop 2, and Total Recall were expected to perform well based on their brand recognition and star appeal. These films were all scheduled for release by the end of June to ensure a long theatrical run during the peak time of the year, and other releases were scheduled to avoid opening against them. The importance of domestic box office grosses was also decreasing as studios increasingly earned profits from home media releases, television rights, and markets outside of the United States and Canada. These growing markets were, in turn, increasing film production costs as stars commanded higher salaries to compensate for their international appeal, with Total Recall, Die Hard 2, and Days of Thunder among the most expensive films being released. Average salaries for male leads had also increased to between $7–$11 million.[85]

Marketing

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Total Recall teaser on YouTube | |

| Total Recall trailer on YouTube |

The teaser for Total Recall, made by distributor Tri-Star Pictures, disappointed Schwarzenegger and tested poorly with audiences. It lacked the action scenes and special effects, and presented the film in a vague, dramatic way. Schwarzenegger believed it "cheapened" the film, saying "it looks like a $20 million movie in this trailer ... it's like a $50 million movie." He contacted Peter Guber, the head of Tri-Star's owner Sony Pictures Studios, who contracted a different company, Cimmaron/Bacon/O'Brien, to produce a new trailer focusing on the action and special effects; it fared much better with audiences and attracted praise from industry professionals, such as Joel Silver.[32]

Box office

editIn the U.S. and Canada, Total Recall was released on June 1, 1990, in 2,060 theaters. It grossed $25.5 million—an average of $12,395 per theater—and finished as the number one film of the weekend, ahead of Back to the Future Part III ($10.3 million), which was in its second weekend of release, and Bird on a Wire ($6.3 million), in its third. This figure gave it the highest opening weekend gross of the year to date, narrowly beating Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles's $25.4 million.[k] This was also the highest opening for an R-rated film,[89] and one of the ten highest-grossing three-day opening weekends ever.[l] The film fell to number two in its second weekend, with an additional gross of $15 million (a decline of forty-one percent), behind the debut of Another 48 Hrs. ($19.5 million), and to the number three position in its third week with an additional gross of $10.2 million, behind Another 48 Hrs. ($10.7 million) and the debut of Dick Tracy ($22.5 million).[90][91]

By mid-July, the film had earned over $100 million and was classified as a success.[92] During the remainder of its sixteen-weekend theatrical run, Total Recall never regained the number one position, leaving the top-ten highest-grossing films by the end of July.[93] Total Recall earned an approximate total box office gross of $119.4 million.[m] This figure made it the second-highest-grossing film of the summer, behind the surprise success of Ghost, and the seventh-highest-grossing film of the year behind The Hunt for Red October ($120.1 million), Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles ($135.3 million), Pretty Woman ($178.4 million), Dances with Wolves ($184.2 million), Ghost ($217.6 million), and Home Alone ($285.8 million).[n]

Figures are unavailable for all theatrical releases outside of the U.S. and Canada, but the film is estimated to have earned a further $142 million, giving it a cumulative worldwide gross of $261.4 million,[o] making it the fifth-highest-grossing film of the year, behind Dances with Wolves ($424.2 million), Pretty Woman ($432.6 million), Home Alone ($476.7 million), and Ghost ($517.6 million).[p] Taking into account production fees, interest, residual payments, and other costs, Total Recall is estimated to have returned $36 million in profit to the studio.[98][q]

Reception

editCritical response

editOn its release, Total Recall received mixed reviews from critics, who generally praised the production values and Schwarzenegger's performance, but criticized the violent content.[39][99][100] Audience polls by CinemaScore reported moviegoers gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[101]

The narrative polarized reviewers; some praised it as an above-average, complex, and visually interesting science fiction film that successfully blends humor with satirization of the genre's tropes,[r] while others found it lacked humor, romance, or a strong narrative structure.[104][106] Gene Siskel and Peter Travers believed the latter half of the film, after Quaid reaches Mars, to be where Total Recall became "mechanical", abandoning logic and artistic ambition for excessive action and violence.[s] Travers described it as a transitory blockbuster in contrast to The Terminator (1984) (also starring Schwarzenegger), which he said would "haunt our dreams".[109] Several reviewers agreed that the hotel confrontation between Quaid and Rekall's Dr. Edgemar on Mars, in which the former learns everything he has experienced is potentially a dream, was the best scene,[103][104][105] and found the concept of overwriting memories and identity to be a genuinely horrifying concept.[103][109] Jonathan Rosenbaum called it a "worthy entry in the dystopian" genre initiated by Blade Runner that avoided being derivative of its predecessors.[110]

The film was often compared to Verhoeven's previous work on RoboCop, with some reviews remarking that Total Recall lacked the same "impudence and incandescence" or satirization of 1980s action films as the earlier film.[103][111][112] Some said the film was only fun when Verhoeven inserted moments of RoboCop's camp style.[111][112] The Washington Post's review compared it unfavorably with the Sylvester Stallone action film Cobra (1986), saying it was disappointing in its overuse of violence and abandonment of cynicism and creativity for machoism and misogyny.[108] Several reviews focused on the excessive violence, with Vincent Canby describing it as part of an influx of action-adventure films featuring numerous deaths, counting seventy-four kills in the film and over two hundred in Die Hard 2.[104][113] Some were concerned by the dismissive and sometimes comical depiction of the deaths, and the general reliance on violence as a solution to all problems posed.[t] Even so, the Los Angeles Times's review said the violence never seemed to be deliberately sadistic or callous.[103] Despite this criticism, Bottin's practical effects were roundly praised, particularly the three-breasted prostitute and mutants that provided many of the film's standout visuals, despite their sometimes perverse or macabre nature.[u]

Reviews praised Schwarzenegger for playing against his public action hero image by portraying a confused, vulnerable, and sympathetic character, with Roger Ebert considering him vital to the film's success.[v] Desson Howe and Travers described it as Schwarzenegger's finest and most interesting work since The Terminator.[109][111] Even so, others believed the actor's "superman presence" and comic one-liners were out of place and undermined attempts to make the audience emotionally connect with Quaid's genuine fears about his identity. Janet Maslin wrote that this was further harmed by the narrative failing to emphasize his dual identities.[103][109] Some reviews considered the role to be beyond Schwarzenegger's acting abilities, describing him as "unusually oafish ... a cross between Frankenstein's monster, a hockey puck, and Colonel Klink", incapable of generating a romantic connection with Stone's or Ticotin's characters.[106][108][109] Some female reviewers were critical of the film's treatment of women, who they perceived as "hybrid hooker-commandos" and "basically whores", writing that the three-breasted prostitute is the film's idea of a "witty mutation" while Ticotin "registers less strongly than Stone's ambiguous, blonde slut-wife".[103][104][108]

Accolades

editAt the 63rd Academy Awards in 1991, Total Recall won the award for Best Visual Effects (Eric Brevig, Rob Bottin, Tim McGovern, and Alex Funke). The film received a further two nominations: Best Sound (Nelson Stoll, Michael J. Kohut, Carlos Delarios, and Aaron Rochin) and Best Sound Effects Editing (Stephen Hunter Flick).[10][114] At the 44th British Academy Film Awards, the film received one nomination, for Best Special Visual Effects (losing to the comedy film Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989)).[115] At the 17th Saturn Awards, Total Recall was named Best Science Fiction Film.[116] It was also nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation (losing to fantasy romance film Edward Scissorhands).[117]

Post-release

editAftermath

editFollowing Total Recall, Schwarzenegger's popularity continued to grow as he went on to star in Kindergarten Cop (1990), Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and True Lies (1994), earning over $1 billion combined at the box office and solidifying his status as the most popular international film celebrity, based on surveys of studio executives and talent agents.[32][118] Verhoeven worked with Stone again when he directed the box office success Basic Instinct (1992) for Carolco.[119][120] Despite their desire to collaborate on another project, Schwarzenegger and Verhoeven did not work together again. Their last attempt to do so, the big-budget historical drama Crusade, was abandoned by Carolco in the mid-1990s in favor of Cutthroat Island (1995), a box office flop that contributed to Carolco entering bankruptcy the same year.[w]

Shusett and Goldman did not like aspects of Total Recall, believing it was overly long and failed to make the audience care about the mutants, as well as disliking the excessive swearing, violence, and deaths. They also thought the special effect of Schwarzenegger's and Ticotin's swelling heads went on too long and, alongside Verhoeven, they regretted the rushed post-production and lack of test screenings to solicit feedback that could have led to a "tighter" re-edit on the third act.[68] Total Recall also failed to impress Cronenberg, who believed Schwarzenegger was not the right actor for the lead role.[23] Two lawsuits followed the film's release. John J. Goncz, a prop maker, sued for $3 million alleging that his credit was removed from Total Recall after he refused permission for Carolco to merchandise a survival knife he made for it. A separate suit, also for $3 million, was brought by the Southern California Consortium, who said Total Recall used animated sequences they had created for scientific videos about planets orbiting the Sun. The outcomes of these lawsuits are unknown.[39]

Home media

editTotal Recall was released on VHS and LaserDisc on November 1, 1990; it was rushed out to take advantage of the Christmas season.[x] It was priced at $24.99, a relatively low figure compared to standard prices closer to $90, because audience research had shown a willingness to purchase the film due to its rewatchability. Although retailers normally avoided selling films with violent or sexual content, they were willing to stock Total Recall.[129] It was predicted to perform well as a purchase and rental.[126][127][128] It became one of the bestselling home entertainment products of the year, in which purchases outperformed rentals for the first time. It was also one of the top rentals in December, trading the number one position back and forth with Pretty Woman.[130][131]

The film was first released on DVD in 2000, and received criticism from IGN for what was perceived as poor image quality. It was followed by a special edition version in 2001 that included a commentary track with Verhoeven and Schwarzenegger and a documentary about the film's production, including its release and subsequent reaction.[132][133] A special Total Recall: Mind-Bending Edition Blu-ray was released in 2012, featuring a high-definition restoration from the original negative. This version included a new interview with Verhoeven and a comparison of the restored footage against the original.[4][134][135] For its 30th anniversary in 2021, the film was remastered as a 4K resolution Ultra HD Blu-ray (including a digital copy) based on a digital scan from the original 35mm film negatives under Verhoeven's supervision.[11] As well as content from the 2012 Blu-ray, this release introduced a 60-minute documentary about the success and failure of Carolco Pictures, and retrospectives on the film score, special effects, and production.[4] A separate 5-disc collectors edition was released with a double-sided poster, art cards, essays about the film and the score on compact disc (CD).[136]

Goldsmith's score was first released on CD in 1990 with 10 tracks. A deluxe edition was released in 2000 with 27 tracks.[137] Coinciding with the 30th anniversary, Quartet Records released the remastered soundtrack on a 2-CD and limited edition 3-Vinyl record set. The anniversary edition included the score plus alternates and source music, restored by Goldsmith's long-time sound mixer Bruce Botnick.[138]

Other media

editA novelization of the film, written by Piers Anthony and based on the script and Dick's original novel, was released in 1990; it retains the original character name of Douglas Quail.[139] That same year, an action-platformer video game, Total Recall, was released for the Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC, and Nintendo Entertainment System, and Amiga, and Atari ST computers. A ZX Spectrum version was planned but cancelled because it would not be ready for the Christmas 1990 release date.[140] A comic book adaptation of the film was also released in 1990 by DC Comics.[141] A 2011 four-issue miniseries comic book was released by Dynamite Entertainment. Written by Vince Moore with art by Cezar Rezak, the series' narrative continues on from the end of the film, depicting Quaid dealing with a Mars still in chaos following Cohaagen's death.[142][143][144]

Themes and analysis

editThemes

editThe main theme of Total Recall is the question of whether or not Quaid's experiences are real or a dream induced by his failed Rekall memory implantation. Despite the film's deviations from Dick's original story, both focus on this theme.[16] Verhoeven explicitly wanted both possibilities to be viable, although his personal preference is that Quaid's experiences are a dream. He explained "it's a dream, which is disturbing to the audience because they don't want that, of course. They want an adventure story, they don't want a fake adventure story. So they are on [Quaid's] side trying to believe that it's all true, while [Dr. Edgemar] is trying to tell him that it's not true."[46] Quaid chooses to believe in his reality and kills Dr. Edgemar.[46] Lori confirming that the Quaid persona is effectively a dream breaks down the barrier between reality and fantasy, leaving Quaid and the audience unable to definitively determine the reality of what they are experiencing.[145]

It is left up to the audience to determine what is real, and because of Schwarzenegger's public image as a superhuman action hero, the possibility remains that Quaid's adventures on Mars are real. Verhoeven said that re-watching the film can induce more doubt in the audience, particularly when the Rekall manager, Bob McClane, effectively outlines everything that will happen to Quaid after the memory implantation. During the same scene, Melina is shown on the Rekall screen before Quaid has met her.[146] At the film's end, Quaid still questions if everything is a dream, and Melina suggests that he kiss her before he wakes up. English professor Jason P. Vest said that by not including herself in Quaid's possible delusion, Melina both suggests and denies she is a creation of Quaid's fantasy.[147] Ironside stated that he believed the film is an analog for manipulating reality for the common people through news and the media at the behest of those in power.[54] Writer Bek Aliev believed that this theme remains relevant in the age of social media, where the line between a person's average life and more curated online life becomes blurred.[148]

Another theme of Total Recall is the meaning of identity in a world where memories are commodities that can be erased or fabricated completely.[149] Vest contrasted this with Blade Runner, in which memory is presented as a precious and vital component of the human experience, while in Total Recall, memories can be easily removed, replaced, or revised and these changes are generally embraced. When Quaid learns that he is really Hauser, he affirms to himself "I am Quaid" and rejects the Hauser personality.[150]

Author David Hughes wrote that Quaid is not an altered version of Hauser but a completely separate personality with his own memories and morality. He contrasted Quaid with Blade Runner's replicants—artificial humans—except that it is Quaid's mind that is artificial. Quaid is forced to choose between returning to his original but antagonistic persona or remaining as the artificial but benevolent construct of Quaid. Hughes considered this an interesting moral choice and true to Dick's work.[47] Quaid is offered a chance at a better life by being restored to Hauser's higher social status, but will lose himself in the process.[48] Goldman believed Quaid's refusal to be the authentic choice because he did not believe someone would willingly and permanently give up their identity.[151] SyFy writer Noah Berlatsky said that as an everyday worker who desires grand adventures, Quaid is an audience stand-in, and suggested the hologram projector that creates a duplicate image of Quaid to be akin to the audience viewing themselves through the phantom personality that is Quaid.[1]

The film presents a politically, morally, and visually unattractive future in which the Earth's locations are covered in brutalist, concrete architecture. Verhoeven specifically chose to use this style because he believed it suggested a cruel society indifferent to the suffering of the Martian colonists as long as turbinium ore mining continues. Mars is represented ubiquitously with various red hues, invoking associations with blood, danger, and a hellish domain.[152][153] The in-film Propaganda networks show reality being altered in real-time, as they brand the resistance as terrorists and describe the indiscriminate slaughter of them as restoring order with minimal use of force.[154]

Analysis

editAccording to Vest and English professor Frank Grady, most political assessments of the film considered it left-wing for its anti-corporation and revolutionary message but Vest perceived a more conservative subtext in which the "white protagonist saves a society of the less well-off who cannot save themselves".[155][156] They identified Total Recall as one of many films produced throughout the 1980s—such as Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) and Predator—that were "fronted by white male characters who employ violence to preserve American righteousness, liberty, autonomy, and reinforce an idealistic American image of combating unnecessary bureaucracy, fascists, communists, and foreign and domestic threats". Schwarzenegger identified himself as a conservative and supporter of U.S. president Ronald Reagan, which Vest opined made him "an unusual choice to portray the protagonist who liberates Mars from Cohaagen's dictatorship".[157][158] Quaid's rejection of the Hauser persona can be seen as an example of self-determination and American exceptionalism, but in doing so he also avoids responsibility or punishment for Hauser's acts, which Grady considered an act of moral cynicism. Historian Stephen Prince described Quaid's choice not as the loss of self, but conscious rejection of it.[157][159] Remarking on the similarities between Total Recall and the science fiction film The Matrix (1999), educator Neal King found that both protagonists begin as discontented workers who learn their life is a fabrication, become instrumental to those rebelling against overwhelming authority, and eventually learn they were deliberately created to quash the rebellion. Any good deeds they perform are a result of who they were programmed to be, meaning their free will is an illusion.[160]

Grady and SyFy writer Stephanie Williams described the privatization of air in Total Recall as the extreme of unchecked corporate power, comparing it to the real world privatization of water sources by companies whose core incentive is to increase profits, such as in the Flint water crisis. The mutants on Mars are the result of early colonists exposed to a toxic atmosphere because of cheap domes, and their offspring still serve Cohaagen, meaning the authorities have escaped any responsibility for their involvement. In the end, Cohaagen suffocates in a toxic atmosphere that he could have changed at any time.[156][161] The film also contains a number of product placements for brands such as Pepsi, Coca-Cola, and Jack in the Box, promoting corporate interests while portraying an anti-corporate stance.[156]

Linda Mizejewski, a professor of women's studies at the Ohio State University, suggests that the name "Cohaagen" is supposed to sound Afrikaans and this, along with the character's links to the mining industry, is part of an analogy between Apartheid-era South Africa, in which there was a highly prosperous mining industry, and sharply defined class divisions, akin to those in the film between the mining executives and the ordinary, oppressed Martians.[162] Likewise, Aliev considered the relationship between the lower classes on Mars and the government to be analogous to real-world colonial and post-colonial social structures, such as Apartheid. The technology that undermines the existing power structure is a metaphor for decolonization and championing the voices of the oppressed.[148] Vest believed Total Recall did not offer a positive representation of minorities, as Benny, the only important African American character, collaborates with Cohaagen and helps assassinate the Martian freedom fighter Kuato. Vest believed that his repeated references to having multiple children "reinforced stereotypes of African American men as irresponsible and promiscuous", and that "his alliance with Cohaagen presents the character as untrustworthy, selfish, and corrupt".[163]

Vest identified certain elements in the film as sexist and misogynistic. Many female characters are presented as prostitutes or mutants, which he believed suggested that "femininity is a source of moral or physical deformity". Many female characters are violently killed throughout, such as Lori, who is dispatched while Schwarzenegger quips that she should "consider that a divorce". However, while Melina is sometimes reliant on Quaid to save her, both she and Lori are portrayed as effective fighters and Melina is essential to saving Quaid's life at the end.[159][164] Union College film studies co-director Michelle Chilcoat wrote that Total Recall began a decade of cyberpunk films that focused on a separation and transformation of the mind away from a traditional human body, such as The Lawnmower Man (1992), Strange Days (1995), and The Matrix. Even so, Chilcoat argues that given the option to become anything via Rekall, Total Recall repeatedly asserts Quaid's heterosexuality.[165]

Legacy

editModern reception

editSince its release, several publications have named Total Recall as one of the greatest science fiction films ever made.[y] Rotten Tomatoes named it one of the 300 essential films to watch,[171] and it is also listed in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[172] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 83% approval rating from the aggregated reviews of 75 critics, with an average score of 7.4/10. The consensus reads, "Under Paul Verhoeven's frenetic direction, Total Recall is a fast-paced rush of violence, gore, and humor that never slacks."[173] The film has a score of 57 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 15 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[174]

In a 2012 retrospective, Vulture wrote that despite its anachronistic aspects, such as outdated technology, Total Recall remained relevant, particularly in its themes of the oppressed fighting back against their oppressors, which was compared to the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement.[175] Discussing the film in 2016, The A.V. Club described it as one of the best 1980s-style action films.[176] Other publications have called it one of Schwarzenegger's most entertaining films and one of his best roles.[154][175][177] The film's score, by Jerry Goldsmith, is considered among his finest work and, in his own words, one of his "greatest scores".[82][83]

A 2020 Inverse retrospective argued that Total Recall, not Blade Runner, was the best adaptation of Dick's work, despite its deviations from the source material. He argued that Blade Runner presented a stylish and cool future, whereas Total Recall presents an "ugly, banal, and grimy" future. Similarly, he believed Quaid's upbeat, amoral antihero protagonist was closer to Dick's traditional protagonists.[178] Even so, Comic Book Resources wrote that "its weirdness and appreciation of dumb-fun" meant that it would probably never be as highly considered as Blade Runner or films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).[148] To mark Schwarzenegger's 75th birthday in 2022, Variety listed Total Recall as the fourth-best film in his 46-year career.[179]

Cultural influence

editTotal Recall became one of the most expensive films ever made in its time, and one of the last big-budget films to use almost entirely practical special effects.[54][102][153] It is also seen as among the films responsible for a significant rise in the costs of film production because of the high salaries studios like Carolco paid to stars with international appeal such as Schwarzenegger, Stallone, and Mel Gibson, recouping their investment by selling their films to the rapidly growing film markets outside of the U.S. and Canada.[41][180] Alongside the boost to Schwarzenegger's career, Total Recall also redefined Stone from a model to a legitimate film star.[32][118][181]

A 2020 SyFy article credited Total Recall as one of three action films, along with Terminator 2 and True Lies (1994), that revived Schwarzenegger's career after a series of less successful action films such as The Running Man (1987), and Red Heat.[99][182] Schwarzenegger recounted coming across the film on television that year, and believing it still held up, saying: "that is really great filmmaking ... when you can, after 30 years, watch a movie and it still feels the same."[32] Schwarzenegger also named his 2012 memoir Total Recall.[183]

In 2020, The Guardian wrote that, with hindsight, Total Recall formed the middle of Verhoeven's unofficial science fiction action film trilogy about authoritarian governance, following RoboCop and preceding Starship Troopers (1997).[154] Quaid's line, "consider that a divorce", after killing Lori, is considered one of Schwarzenegger's most iconic one-line quips from his filmography,[148][176][154] and the three-breasted prostitute, portrayed by Lycia Naff, is regarded as an iconic character in cinematic history.[7][11] Although she eventually came to terms with the role, Naff was initially embarrassed by her appearance in Total Recall and avoided interviews or fan interactions, saying "I decided not to answer every letter from every prisoner in the world who was writing to me ..."[184]

Total Recall influenced films such as The Matrix, The 6th Day (2000), also starring Schwarzenegger, as well as other media such as Rick and Morty, South Park, and The Expanse.[z] It has been referenced in politics when, during his 2020 address to the Austrian World Summit climate conference about the urgency of their 2050 climate neutrality goal, Dutch politician and European Commissioner for Climate Action, Frans Timmermans, said, "it's been 30 years since Total Recall and Kindergarten Cop — I mean these things go so fast ... we have to act now and we can."[188]

Sequel and adaptations

editTotal Recall's success led to development of a sequel. Goldman had optioned another of Dick's works, the 1956 novella The Minority Report, intending to direct it himself. Unable to make progress on that project, he and Shusett worked together on adapting The Minority Report into a Total Recall sequel in 1993, depicting Quaid as the head of an organization that uses mutants with precognition abilities to predict and stop crimes before they happen.[16][39][189] Carolco struggled to secure either funding or Schwarzenegger's interest to progress the project before its bankruptcy.[190][191][189] The television rights to Total Recall were bought by DFL Entertainment for $1.2 million to develop the television series Total Recall 2070 (1999).[63][192][193] The show, set entirely on Earth, was not based on the film and was described by author David Hughes as closer to a Blade Runner adaptation.[63][194] In the interim, Shusett and Goldman had removed the Total Recall elements from their script to develop it as a standalone film, Minority Report (2002).[16][189]

The film rights to Total Recall were bought by Dimension Films for $3.15 million at Carolco's bankruptcy auction.[63][192][193] The studio began development of a sequel, intending to bring back the principal cast, but not Verhoeven. Matt Cirulnick developed a script, but Shusett's original contract guaranteed him first draft rights to a sequel and he, based on an earlier agreement, was obliged to work with Goldman.[aa] The pair's story continued from the end of Total Recall with Mars now an independent planet. The rebels explore Quaid's mind for Hauser's memories of a mind-control project. It featured several twists, including Quaid waking up at Rekall on Earth, and other hints that he is living within a dream.[195][196][197] Schwarzenegger became actively involved by 1998, but believed their idea was overly complicated.[198][191] Cirulnick wrote another draft, revealing that Hauser and Quaid are both fabricated personalities, and depicting the destruction of Mars to save Earth from a bomb placed in the Sun. This draft was well received by Dimension, but he was asked to rewrite it to lower the budget.[189] Development eventually ceased as a series of failed films had harmed Dimension financially, and the studio was unable to reach an agreement with Schwarzenegger.[189][199]

The rights to Total Recall were eventually purchased by Columbia Pictures and a remake was announced in 2009.[200] Released in 2012, the film, also called Total Recall, starred Colin Farrell, Bryan Cranston, Kate Beckinsale, and Jessica Biel. Its plot follows elements of the 1990 film but omits Mars entirely, taking place on a mostly uninhabitable Earth.[201][202] The film failed to replicate the financial or critical success of the original.[ab]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[3][12][13][14]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[13][14][16][17][20][21]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[13][14][16][28][29]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[35][37][38][39]

- ^ Arnold Schwarzenegger's estimated $10–$11 million salary, minus his share of film profits, is equivalent to $23.3 million–$25.7 million in 2023

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[7][10][38][60]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[39][61][62][63]

- ^ The estimated budget of $48–$80 million is equivalent to $112 million–$187 million in 2023

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[5][18][55][64][65][66][67]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[67][71][72][73]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[32][86][87][88]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[32][86][87][88]

- ^ The United States and Canada box office of $119.4 million is equivalent to $278 million in 2023

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[16][94][95][96]

- ^ The worldwide 1990 box office of $261.4 million is equivalent to $610 million in 2023

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[16][32][39][97]

- ^ Carolco Pictures is estimated to have earned $36 million in profit from the theatrical box office, equivalent to $84 million in 2023

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[102][103][104][105]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[104][106][107][108][109]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[103][104][107][108][113]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[72][104][109][112]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[103][104][105][112]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[32][119][121][122][123][124][125]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[126][127][128][129]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[166][167][168][169][170]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[148][153][175][176][185][186][187]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[189][190][191][195][193]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[100][203][204][205]

Sources

edit- ^ a b c d Berlatsky, Noah (July 11, 2020). "30 Years Later, Total Recall Still Understands Escapism Better Than Most Fantasy". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (March 22, 2011). "Eva Mendes, Kate Bosworth, Diane Kruger Among Actresses Reading for Female Leads in Total Recall Remake". Collider. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kaye, Don (December 7, 2020). "How Total Recall Brought a Memorable Villain to Life". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c Szadkowski, Joseph (December 22, 2020). "Total Recall 4K Ultra HD movie review". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Damore, Meagan (December 7, 2020). "Total Recall Star Marshall Bell Reflects on the Film's Enduring Legacy". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Lambie, Ryan (December 7, 2020). "Total Recall's Richter: A Day in the Life of Cinema's Unluckiest Villain". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on February 17, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Pockross, Adam (June 25, 2020). "When Mel Johnson Jr. First Read Total Recall's Description Of Benny, He Threw The Script Across The Room". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "Greatest Film Plot Twists, Film Spoilers and Surprise Endings". Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "Total Recall (1990)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Pockross, Adam (June 1, 2020). "Total Recall At 30: Cohaagen, Benny & Johnny Cab Recall Paul Verhoeven's Mind-bending Masterpiece". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Vineyard, Jennifer (August 3, 2012). "A Candid Conversation With Total Recall's Original Three-Breasted Woman". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Hughes 2012, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Murray 1990, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e Murray 1990b, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Hughes 2012, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Rose, Frank. "The Second Coming of Philip K. Dick". Wired. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2012, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Dee, Jake (September 3, 2020). "10 Behind-The-Scenes Facts About The Making of Total Recall". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Murray 1990b, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Broeske, Pat H. (December 4, 1988). "Spaced Out". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts 1990, p. 6.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 78.

- ^ a b Hughes 2012, p. 65.

- ^ Hughes 2012, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2012, p. 63.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 8.

- ^ Hughes 2012, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Vest 2009, p. 48.

- ^ Ruimy, Jordan (May 25, 2016). "Interview: Paul Verhoeven Talks Elle, Why Well Known Actresses Turned It Down & The Problem With Hollywood". The Playlist. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2012, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Siegel, Alan (June 4, 2020). "Arnold Schwarzenegger's Mission to Mars". The Ringer. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b Murray 1990, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b c d Murray 1990b, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2012, p. 67.

- ^ "Carolco Signs Deal for DEG: Carolco Pictures signed a...". Los Angeles Times. April 21, 1989. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Murray 1990, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Mathews, Jack (September 3, 1989). "The Man Inside the Muscles : From Mr. Universe to Mr. Hollywood--How Arnold Schwarzenegger got the last laugh". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Total Recall". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 11, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "The 101 Most Powerful People in Entertainment". Entertainment Weekly. November 2, 1990. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Fabrikant, Geraldine (December 10, 1990). "The Hole in Hollywood's Pocket". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c Roberts 1990, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Hughes 2012, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Hughes 2012, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Hughes 2012, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Hughes 2012, p. 68.

- ^ a b Hughes 2012, p. 69.

- ^ a b Hughes 2012, p. 70.

- ^ Murray 1990, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c Murray 1990, p. 54.

- ^ Hughes 2012, pp. 66, 71, 88.

- ^ Murray 1990b, pp. 30, 72.

- ^ a b Murray 1990b, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d Slater-Williams, Josh (November 24, 2020). "I can remember it for you wholesale: The making of Total Recall, 30 years on". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c VanHoose, Benjamin (June 5, 2020). "Arnold Schwarzenegger Suffered a 'Deep' Wrist Wound While Shooting Total Recall 30 Years Ago". People. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Sue (July 28, 1990). "Mel Johnson Jr. Happy to Be in Total Recall's Driver's Seat". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Pockross, Adam (June 19, 2020). "Ronny Cox Only Played 'Boy Scout Nice-guys' Until Paul Verhoeven Turned Him Bad". Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Erbland, Kate (April 19, 2012). "24 Things We Learned from Paul Verhoeven's Total Recall Commentary". Film School Rejects. Archived from the original on May 19, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Pecchia, David (March 26, 1989). "Films now going into production: ...". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Armstrong, Vic (May 12, 2011). "What was it like being a stunt director on Total Recall?". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (December 7, 1989). "It's Fade-Out for the Cheap Film As Hollywood's Budgets Soar". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Vest 2009, pp. 29, 184.

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2012, p. 77.

- ^ Malkin, Elisabeth (May 22, 2014). "Golden Line Adds Tarnish to Sprawling Subway System". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Rother, Larry (January 1, 1990). "A New Star For Studios Is Mexico". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Scene In Nevada: Total Recall". Nevada Film Office. May 16, 2016. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Allis, Tim (July 16, 1990). "A Face You Can't Totally Recall? Bad Guy Michael Ironside Chased Arnold Schwarzenegger to Mars". People. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2012, p. 72.

- ^ "Total Recall (18)". British Board of Film Classification. June 13, 1990. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "Why Total Recall's Underrated". Esquire Middle East. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Murray 1990b, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Magid, Ron (March 2, 2020). "Many Hands Make Martian Memories in Total Recall". American Cinematographer. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Failes, Ian (June 4, 2015). "Recalling Total Recall". Fxguide. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- ^ Murray 1990b, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Zalben, Alex (December 4, 2020). "Total Recall 30th Anniversary: Get an Exclusive Look Behind the Scenes at the Mars That Almost Was". Decider. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Roberts 1990, pp. 13, 15, 19–20, 22, 31–32.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 8.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 23.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 31.

- ^ Roberts 1990, p. 32.

- ^ a b Wilson, Sean (March 16, 2017). "Saluting the Film Scores of Paul Verhoeven Movies". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Chapman, Glen (September 14, 2010). "Music in the movies: the sci-fi themes of Jerry Goldsmith". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Clemmensen, Christian (April 28, 2021). "Total Recall". Filmtracks.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (June 3, 1990). "Film; For Summer Films, Position Is (Almost) Everything". The New York Times. pp. 13, 17. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ a b "Domestic 1990 Weekend 22 June 1–3, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Richard W. (June 22, 1990). "A Real Blockbuster, Or Merely a Smash?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Broeske, Pat H. (June 4, 1990). "Total Recall Totally Dominates Box Office : Movies: Film starring Schwarzenegger posts one of the top 10 biggest three-day openings ever". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Variety, June 1996, p. 6.

- ^ "Domestic 1990 Weekend 23 June 8–10, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Domestic 1990 Weekend 24 June 15–17, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (July 12, 1990). "Hollywood Looks Beyond Mayhem For a Blockbuster". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Total Recall". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Top 1990 Movies at the Domestic Box Office". The Numbers. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (September 22, 1990). "Love Conquers All in Hollywood Summer Season". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (November 3, 1990). "Top Movie Of the Year A Sleeper: It's Ghost". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Top 1990 Movies at the Worldwide Box Office". The Numbers. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Stevenson, Richard W. (June 26, 1991). "Carolco Flexes Its Muscle Overseas". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Broeske, Pat H. (June 5, 1990). "Recall Totally Outdistances Future in Box-Office Race : Movies: Schwarzenegger's sci-fi flick opens with $25.5 million. But it only just edges the Turtles $25.3-million record". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Jones, Mike (June 23, 2021). "Chance The Rapper Argues Eddie Murphy Should Have Starred In Total Recall". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on July 3, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "Cinemascore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "Total Recall". Variety. January 1, 1990. Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wilmington, Michael (June 1, 1990). "Movie Review : Total Schwarzenegger : Film: Paul Verhoeven's futuristic action-thriller Total Recall plunges the muscular hero in a deadly game of mind over matter". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maslin, Janet (June 1, 1990). "Review/Film; A Schwarzenegger Torn Between Lives on Earth and Mars". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger (June 1, 1990). "Total Recall". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Steinmetz, Johanna (June 1, 1990). "Faulty Recall". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene (June 1, 1990). "Total Recall Starts Well". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Kempley, Rita (June 1, 1990). "Total Recall (R)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Travers, Peter (June 1, 1990). "Total Recall". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Total Recall". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on June 29, 2008. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Howe, Desson (June 1, 1990). "Total Recall (R)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Gleiberman, Owen (June 8, 1990). "Total Recall (1990)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2021.