Dorking (/ˈdɔːrkɪŋ/) is a market town in Surrey in South East England about 21 mi (34 km) south of London. It is in Mole Valley District and the council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs roughly east–west, parallel to the Pipp Brook and along the northern face of an outcrop of Lower Greensand. The town is surrounded on three sides by the Surrey Hills National Landscape and is close to Box Hill and Leith Hill.

| Dorking | |

|---|---|

| Market town | |

View northeast from The Nower towards Dorking town centre and Box Hill | |

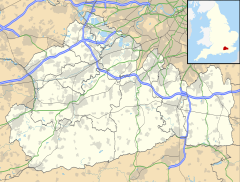

Location within Surrey | |

| Area | 6.57 km2 (2.54 sq mi) town wards[1] |

| Population | 11,158 town wards only[1] 17,098 wider built-up area[2] (2011 census) |

| • Density | 1,698/km2 (4,400/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ165494 |

| • London | 21 mi (34 km) NNE |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Dorking |

| Postcode district | RH4 |

| Dialling code | 01306 |

| Police | Surrey |

| Fire | Surrey |

| Ambulance | South East Coast |

| UK Parliament | |

The earliest archaeological evidence of human activity is from the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, and there are several Bronze Age bowl barrows in the local area. The town may have been the site of a staging post on Stane Street during Roman times, however the name 'Dorking' suggests an Anglo-Saxon origin for the modern settlement. A market is thought to have been held at least weekly since early medieval times and was highly regarded for the poultry traded there. The Dorking breed of domestic chicken is named after the town.

The local economy thrived during Tudor times, but declined in the 17th century due to poor infrastructure and competition from neighbouring towns. During the early modern period many inhabitants were nonconformists, including the author, Daniel Defoe, who lived in Dorking as a child. Six of the Mayflower Pilgrims, including William Mullins and his daughter Priscilla, lived in the town before setting sail for the New World.

Dorking started to expand during the 18th and 19th centuries as transport links improved and farmland to the south of the centre was released for housebuilding. The new turnpike, and later the railways, facilitated the sale of lime produced in the town, but also attracted wealthier residents, who had had no previous connection to the area. Residential expansion continued in the first half of the 20th century, as the Deepdene and Denbies estates began to be broken up. Further development is now constrained by the Metropolitan Green Belt, which encircles the town.

Toponymy

editThe origins and meaning of the name Dorking are uncertain.[3] Early spellings include Dorchinges (1086),[4] Doreking (1138–47),[3] Dorkinges (1180),[5] and Dorkingg (1219).[3] Both principal elements in the name are disputed. The first element may be from a personal name, Deorc, or some variant, of either Brittonic or Old English origin. Alternatively it may derive from the Brittonic words Dorce, a river name meaning "clear, bright stream", or duro, meaning a "fort", "walled town" or "gated place".[3][6] The second element, if originally plural (‑ingas), might mean "(settlement belonging to the) followers of ...", but if singular (‑ing) might mean "place", "stream", "wood" or "clump".[3]

Geography

editLocation and topography

editDorking is in central Surrey, about 21 mi (34 km) south of London and 10 mi (16 km) east of Guildford. It is close to the intersection of two valleys – the north-south Mole Gap (where the River Mole cuts through the North Downs) and the west–east Vale of Holmesdale (a narrow strip of low-lying land between the North Downs and the Greensand Ridge).[7][8] The highest point in the town is the Glory Wood, south east of the centre, where the summit (137 m (449 ft)) is marked by a Bronze Age bowl barrow.[9]

The basic plan of the town centre has not changed since medieval times (and may be Anglo-Saxon in origin).[10] The main streets (the High Street, West Street and South Street) meet at Pump Corner, forming a " Y " shape.[11][12] Together, West Street and the High Street run approximately west–east, paralleling the Pipp Brook, a tributary of the Mole, which runs to the north of the centre.[13]

The town is surrounded by the Metropolitan Green Belt (which also covers the Glory Wood) and is bordered on three sides by the Surrey Hills National Landscape. Several Sites of Special Scientific Interest are close by, including the Mole Gap to Reigate Escarpment, immediately to the north.[14] The National Trust owns several properties in the area, including Box Hill,[15] Leith Hill Tower[16] and Polesden Lacey.[17]

Geology

editThe rock strata on which Dorking sits, belong primarily to the Lower Greensand Group. This group is multilayered and includes the sandy Hythe Beds, the clayey Sandgate Beds and the quartz-rich Folkestone Beds.[18] The lower greensand was deposited in the early Cretaceous, most likely in a shallow sea with low oxygen levels. Over the subsequent 50 million years, other strata were deposited on top of the Lower Greensand, including Gault clay, Upper Greensand and the chalk of the North and South Downs.[19]

Following the Cretaceous, the sea covering the south of England began to retreat and the land was pushed higher. The Weald (the area covering modern-day south Surrey, south Kent, north Sussex and east Hampshire) was lifted by the same geological processes that created the Alps, resulting in an anticline which stretched across the English Channel to the Artois region of northern France.[20] Initially an island, this dome-like structure was drained by the ancestors of the rivers which today cut through the North and South Downs, including the Mole.[21] The dome was eroded away over the course of the Cenozoic, exposing the strata beneath and resulting in the escarpments of the Downs and the Greensand Ridge.[22]

In Dorking, the dividing line between the Lower Greensand and Gault clay is marked by the course of the Pipp Brook. In the south of the town, the Hythe Beds take the form of iron-rich, soft, fine-grained sandstone,[23] whereas the Sandgate Beds have a more loamy composition.[24] The quartz-rich Folkestone Beds have a lower iron content, and contain veins of silver sand and rose-coloured ferruginous sand.[25] Running along the north bank of the Pipp Brook (with a width of around 200 m (200 yd)) is the outcrop of Gault, a blue-black shaly clay,[26] beyond which is a narrow band of Upper Greensand, a hard, grey mica-rich sandstone.[27] In the extreme north west of the town, the marly Lower Chalk was quarried for lime production until the early 20th century.[28]

Ammonite fossils are found in the north of the town, including Stoliczkia, Callihoplites, Acanthoceras and Euomphaloceras species in the Lower Chalk and Puzosia species in the Upper Greensand.[29] Foraminifera fossils have been found in the Hythe Beds adjacent to the Horsham road, to the west of Tower Hill.[30]

History and development

editPre-history

editThe earliest evidence of human activity in Dorking comes from the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods and includes flint tools and flakes found during construction development in South Street.[31][32][33] During the rebuilding of the Waitrose supermarket in South Street in 2013, charred hazelnut shells, radiocarbon dated to between 8625 and 8465 BCE, were discovered.[34] A ring ditch containing two ceramic urns, was also found.[35] Other ditches identified during the same excavation may indicate the presence of a Bronze Age field system, although the date of these later earthworks is less certain.[34] Bowl barrows from the same period have been found at the Glory Wood (to the south of the town centre),[9] on Milton Heath (to the west)[36] and on Box Hill (to the northeast).[37][38][note 1]

Roman and Saxon

editThere is thought to have been a settlement at Dorking in Roman times, although its size and extent are unclear. Coins from the reigns of Hadrian (117–138 AD), Commodus (180–192) and Claudius Gothicus (214–270), as well as tiles and pottery fragments, have been found in the town.[10] Stane Street, the Roman road linking London to Chichester, was constructed during the first century AD[46] and is thought to have run through Dorking.[10] The exact course through the town is not known and no definitive archaeological evidence has been discovered for the route in the 3 mi (5 km) gap between the crossing of the River Mole at the Burford Bridge and North Holmwood.[10][47] A posting station is thought to have been located in the area and sites have been proposed in the town centre,[48] at Pixham[10] and at the Burford Bridge, where the road crossed the River Mole.[10][49]

Although the name Dorking implies a settlement that was well established by the time of the Norman Conquest, archaeological evidence of Saxon activity in the town centre is limited to pottery sherds.[31][32][33] Probable Saxon cemeteries have been found close to Yew Tree Road (to the north of the centre)[50] and at Vincent Lane (to the west).[51] In 1817, the so-called "Dorking Hoard" of around 700 silver pennies, dating from the mid-8th to the late-9th centuries, was found near the source of the Pipp Brook on the northern slopes of Leith Hill.[52][53][note 2] In the late Saxon period, the manor and parish were administered as part of the Wotton Hundred[54] and may have been part of a large royal estate centred on Leatherhead.[13]

Governance

editDorking appears in Domesday Book of 1086 as the Manor of Dorchinges. It was held by William the Conqueror, who had assumed the lordship in 1075 on the death of Edith of Wessex, widow of Edward the Confessor. The settlement included one church, three mills worth 15s 4d, 16 ploughs, woodland and herbage for 88 hogs and 3 acres (1.2 ha) of meadow. It rendered £18 per year in 1086. The residents included 38 villagers, 14 smallholders and 4 villeins, which placed it in the top 20% of settlements in England by population.[13][55]

In around 1087, William II granted the manor of Dorking to Willam de Warenne, the first Earl of Surrey, whose descendants have held the lordship almost continuously until the present day.[13] By the early 14th century, the manor had been divided for administrative purposes into four tithings: Eastburgh and Chippingburgh (corresponding respectively to the eastern and western halves of the modern town); Foreignburgh (the area covered by the Holmwoods) and Waldburgh (which would later be renamed Capel).[12] On the death of the seventh Earl, John de Warenne, in 1347, the manor passed to his brother-in-law, Richard Fitzalan, the third Earl of Arundel. In 1580 both Earldoms passed through the female line to Phillip Howard, whose father, Thomas Howard, had forfeited the title of Duke of Norfolk and had been executed for his involvement in the Ridolfi plot to assassinate Elizabeth I.[56] The dukedom was restored to the family in 1660, following the accession of Charles II.[57]

As the status of the de Warennes and their descendants increased, they became less interested in the town. In the 14th and 15th centuries, prominent local families (including the Sondes and the Goodwyns) were able to buy the leases on some of the lordship lands.[58][59] One such area was the Deepdene, first mentioned in a court roll of 1399. This woodland was held by several tenants, before being inherited in 1652 by Charles Howard, the fourth son of the 15th Earl of Arundel, in whose family it remained until 1790. The estate was expanded by successive owners, including the Anglo-Dutch banker Thomas Hope and his eldest son Henry Thomas Hope, who commissioned William Atkinson to remodel the main house as a "sumptuous High Renaissance palazzo".[60][note 3]

Unlike the neighbouring towns of Guildford and Reigate, Dorking was never granted a Borough Charter and remained under the control of the Lord of the Manor throughout the Middle Ages.[12] Reforms during the Tudor period reduced the importance of manorial courts and the day-to-day administration of towns such as Dorking became the responsibility of the vestry of the parish church.[63][64] There was little change in local government structure over the subsequent three centuries, until the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 transferred responsibility for poor relief to the Poor Law Commission, whose local powers were delegated to the newly formed poor law union in 1836.[65][note 4] In 1841, the Dorking Union constructed a new workhouse, south of the town centre, designed by William Shearburn. The entrance block still stands and is now part of Dorking Hospital.[66]

A local board of health (LBH) was established in Dorking in 1881 to administer infrastructure including roads, street lighting and drainage. The LBH organised the first regular domestic refuse collection and, by mid-1888, had created a new sewerage system (including a treatment works at Pixham).[67][61] The Local Government Act 1888 transferred many administrative responsibilities to the newly formed Surrey County Council and was followed by an 1894 Act that created the Dorking Urban District Council (UDC).[67][61] Initially the offices of the UDC were in South Street,[67] but in 1931 the Council moved to Pippbrook House, a Gothic Revival country house to the north east of the town centre, designed as a private residence by George Gilbert Scott in 1856.[68][69][note 5]

The Local Government Act 1972 created Mole Valley District Council (MVDC), by combining the UDCs of Dorking and Leatherhead with the majority of the Dorking and Horley Rural District. In 1984, the new council moved into purpose-built offices, designed by Michael Innes, at the east end of the town.[70]

Transport and communications

editFollowing the end of Roman rule in Britain, there appears to have been no systematic planning of transport infrastructure in the local area for over a millennium. During Saxon times, the section of Stane Street between Dorking and Ockley was bypassed by the longer route via Coldharbour and the upper surface of the Roman road was most likely quarried to provide stone for local building projects.[71] Two routes linked the town to London, the first via the Mole crossing at Burford Bridge to Leatherhead[note 6] and the second, the "Winter Road", climbed the south-facing scarp slope of Box Hill from Boxhurst and ran northeastwards to meet the London-Brighton road at Tadworth.[71][note 7]

The development of Guildford (12 mi (19 km) to the west) was stimulated by the construction of the Wey Navigation in the 1650s.[73] In contrast, although several schemes were proposed to make the Mole navigable, none were enacted[74][75] and transport links to Dorking remained poor. As a result, the local economy began to suffer and the town declined through the late 17th and early 18th centuries.[71]

The turnpike road through Dorking was authorised by the Horsham and Epsom Turnpike Act of 1755.[76][note 8][note 9] The new turnpike dramatically improved the accessibility of the town from the capital and a report from 1765 noted both that the Thursday grain market had increased in size and that the local flour mills were significantly busier.[78] A mail coach operated return journeys between Dorking and London six days per week and several stagecoaches used the route daily until the mid-19th century.[79] In contrast, the east–west Reigate–Guildford road remained the responsibility of the parishes through which it ran and only minimal improvements were made before the start of the 20th century.[77]

The first railway line to reach Dorking was the Reading, Guildford and Reigate Railway (RG&RR), authorised by Acts of Parliament in 1846, 1847 and 1849.[80] Dorking station (now Dorking West) was opened in 1849 northwest of the town, initially as a temporary terminus for trains from Reigate.[81] Local residents had expressed a preference for the station to be sited closer to the town centre at Meadowbank, but since the line passed through a deep cutting at this point it was deemed impractical to provide the necessary freight facilities at this location.[82] Two years later a second station, now known as Dorking Deepdene, was opened on the same line.[83][note 10]

The second railway line to serve the town was authorised by Acts of Parliament in 1862 and 1864[84] and was opened by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway in 1867.[85][86] A west-south connecting spur to the RG&RR was provided on opening, but was removed around 1900, before being briefly restored between 1941 and 1946 as a wartime resilience measure.[84][note 11]

Dorking station was provided with extensive goods facilities, a locomotive yard and a turntable (later the site of the car park).[85] It was built with two platforms, but a third was added in 1925, when the railway line was electrified from Leatherhead.[87][note 12] The original building was demolished in 1980 and was replaced by a larger structure, designed by Gordon Lavington, which integrated the station with offices for Biwater.[88]

In the late 1920s, improvements were made to the Dorking-Reigate road (now the A25), including the construction of Deepdene Bridge over the River Mole.[89][90] The bypass road (now the A24) was opened in 1934[91] following considerable local opposition to the route, which cut through the Deepdene estate.[92][93]

Commerce and industry

editA market at Dorking is first recorded in 1240 and in 1278, the sixth Earl of Surrey, John de Warenne, claimed that it had been held twice weekly since "time out of mind".[94] The early medieval market was probably centred around Pump Corner and between South Street and West Street, but it appears to have moved east to the widest part of the High Street by the early 15th century.[12]

In the century following the Norman conquest, agricultural activity was focused on the lordship lands, which lay to the north of the Pipp Brook. However, as the Middle Ages progressed, woodland to the south and west of the centre was cleared enabling farms owned by the Goodwyns, Stubbs and Sondes families to expand.[58] By the start of the Tudor period, there were at least five watermills in Dorking – two at Pixham (one on the Pipp Brook, owned by the Sondes and one on the Mole, owned by the Brownes), two close to the town centre (both owned by the manor) and one at Milton, on the road to Westcott. There may also have been a windmill on Tower Hill.[59]

The town flourished in Tudor times and, in the 1590s, a market house was built between what is now St Martin's Walk and the White Horse Hotel.[11][note 14] The antiquarian John Aubrey, who visited the town between 1673 and 1692, noted that the weekly market (which took place on Thursdays) was "the greatest... for poultry in England" and noted that "Sussex wheat" was also sold.[97] The free-draining Lower Greensand found in the Dorking area is particularly suited for rearing chickens and the local soils provide grit to assist the birds' digestive systems.[98] The Dorking fowl, which has five claws instead of the normal four, is named after the town.[99][note 15]

Wine made from the wild cherries that grew in the town was another local speciality. A 'cherry fair' was held in July in the 17th and 18th centuries,[100] and was revived in the 20th century at St Barnabas Church, Ranmore. Aubrey also recorded that an annual fair took place on Ascension Day.[97]

Chalk and sand were quarried in Dorking until the early 20th century. Chalk was dug from a pit on Ranmore Road and heated in kilns to produce quicklime.[note 16] In the medieval and early modern periods, the lime was used to fertilise local farm fields, but from the 18th century onwards (and especially after the construction of the turnpike to Epsom in 1755), it was transported to London for use in the construction industry.[102][note 17] Sand from the Folkestone Beds was quarried from several sites in the town, including at two pits in Vincent Lane.[104]

Caves and tunnels were also dug in the sandstone under several parts of the town. Many were used as cellars for storing wine bottles,[105] but deeper workings followed seams of silver sand, which was used in glass making.[106] Most of the surviving caves are privately owned and not accessible to the public. A well-known example is the cockpit beneath the former Wheatsheaf Inn in the High Street, in which fighting cocks were set against each other for sport. During the construction of the car park to the south of Sainsbury's supermarket, the builders broke through into a large cavern of unknown date, the walls of which were painted with trompe-l'œil pillars. Unfortunately, in order to complete the car park, it was necessary to fill in the cave with concrete.[104] Guided tours of the caves in South Street are held on a regular basis and are organised by Dorking Museum.[107]

By the start of the 19th century, increasing mechanisation of agriculture was leading to a local surplus of labour. The wages for unskilled farm workers were decreasing, exacerbated by a fall in produce prices following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Like many towns in the south of England, Dorking was affected by civil unrest among its poorest residents.[108] In November 1830 a riot broke out and a mob of 80 attacked the Red Lion Inn in the High Street. A troop of soldiers from the Life Guards regiment was called in to restore order.[109] In 1831 it was noted that the town (population 4711) had one of the highest rates of poor relief in Surrey.[108]

In early 1832, the vestry devised a supported scheme to enable young unemployed, unskilled labourers to leave the town to settle in Upper Canada.[note 18] The cost of the voyage from Portsmouth to Montreal for 61 recipients of poor relief was paid by private donations, however the emigrants also received an allowance for food and clothing from parish funds. Although many were young, single men aged 14–20, a few families also joined the group.[note 19] Most appear to have settled in the Toronto area, but a few are recorded as living in Kingston, Ontario.[108]

In 1911, the town was described in the Victoria County History as "almost entirely residential and agricultural, with some lime works on the chalk, though not so extensive as those in neighbouring parishes, a little brick-making, watermills (corn) at Pixham Mill, and timber and saw-mills."[61]

Residential development

editAlthough the turnpike road through Dorking had been constructed in the 1750s,[77] the built-up part of the town had changed little by the start of the 19th century.[112] Most of the local professional class and wealthier tradesmen lived along the three main streets (the High Street, West Street and South Street), whilst the often crowded houses of artisans and labourers tended to be in the narrower lanes and alleys. Poor sanitation was still a major problem for the poorer residents and, in 1832, a cholera outbreak was recorded in Ebenezer Place (north of the High Street), where 46 people were crammed into nine cottages.[112]

Nevertheless, Dorking was beginning to attract more affluent residents, many of whom had accumulated their wealth as businessmen in London. Charles Barclay (a Southwark brewery owner) and the bankers Joseph Denison and Thomas Hope (none of whom had any previous connection with the area) purchased the estates at Bury Hill, Denbies and Deepdene respectively. Higher-status individuals living closer to the town centre included William Crawford, the City of London MP, and Jane Leslie, the Dowager Countess of Rothes.[112] Although the incoming landowners played little part in local commerce, they appear to have been the driving force behind schemes to pave streets and to provide gas lighting (both paid for by public subscription).[113]

Rose Hill, the first planned residential estate in Dorking, was developed by William Newland, a wealthy Guildford surgeon, who also had interests in the Wey and Arun Canal. Newland purchased the "Great House" on Butter Hill and the surrounding 6.5 ha (20 acres) of land in 1831, which he divided into plots for 24 houses, arranged around a central paddock, known as "The Oval". The Great House was divided into two separate dwellings (Butter Hill House and Rose Hill House), adjacent to which a mock-Tudor arch was erected over the main carriageway entrance from South Street. Initially sales were slow, but the proposals for the building of the railway line from Redhill stimulated interest in the development in the late 1840s. Although most of the purchasers were private individuals (the majority of whom had been born outside of the local area), the Dorking Society of Friends bought one of the plots in 1845 for the construction of a meeting house.[112][114] By 1861 the estate was complete.[112]

The arrival of the railway in 1849 catalysed the expansion of the town to the south and west. Between 1850 and 1870, the National Freehold Land Society was responsible for housing developments in Arundel and Howard Roads, as well as around Tower Hill. Poorer quality houses were built along Falkland and Hampstead Roads (many of which were replaced in the 1960s and 1970s). Holloway Farm was sold in 1870 and the first houses in Knoll, Roman and Ridgeway Roads were constructed before 1880. Houses in Cliftonville (named after its promoter, Joseph Clift, a local chemist) were also built around the same time.[115] To the north of the High Street, smaller semi-detached and terraced houses were constructed in the 1890s for artisans in Rothes Road, Ansell Road, Wathen Road, Hart Road and Jubilee Terrace.[115]

No significant residential expansion took place in Dorking in the first two decades of the 20th century. In the 1920s and 1930s, the breakup of the Deepdene and Pippbrook estates (and the electrification of the railway line from Leatherhead) stimulated housebuilding to the north and east of the town, including Deepdene Vale and Deepdene Park.[116][117] The sale of part of Bradley Farm (part of the Denbies estate) in the 1930s, enabled the building of Ashcombe, Keppel and Calvert Roads. The Dorking UDC intended to build housing on the rest of the farm (now Denbies Wine Estate), however their plans were interrupted by the outbreak of war and were ultimately prevented by the creation of the Metropolitan Green Belt.[116]

The first council housing was built in Dorking by the UDC in Nower Road in 1920 and similar developments took place in Marlborough and Beresford Roads later the same decade. In 1936, the council obtained a Slum Clearance Order to demolish 81 properties in Church Street, North Street, Cotmandene and the surrounding areas. In total 217 residents were displaced, many of whom were rehoused by the UDC in the Fraser Gardens estate, designed by the architect George Grey Wornum.[note 20] The Chart Downs estate to the southeast of the town was built between 1948 and 1952.[118][119]

Controversially,[120][121] in the late 1950s and 1960s, Dorking UDC constructed the Goodwyns estate on land compulsorily purchased from Howard Martineau, a major local benefactor to the town. The initial designs were by Clifford Culpin and the project was subsequently developed by William Ryder, who was responsible for the erection of the Wenlock Edge and Linden Lea tower blocks.[118] Both the design of the buildings and the layout of the estate were praised in the early 1970s by architectural historians Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner.[122]

Religion

editThe first mention of a church at Dorking occurs in Domesday Book of 1086.[55] In around 1140, Isabel de Warenne, the widow of the second Earl of Surrey, granted the church and a tithe of the rents from the manor to Lewes Priory in Sussex. In the 1190s, the tithe was converted to a pension of £6, which was paid annually to the Priory until at least 1291.[123] The Priory also acquired the right to appoint the town's priest.[124]

It is unclear where in the town the Domesday church was located. It appears to have been replaced at some point during the 12th century (possibly by Isabel de Warenne) by a large cruciform building with a central tower.[124] A rededication from St Mary to St Martin may have taken place around the same time.[123] In 1334 the church was granted to the Priory of the Holy Cross in Reigate.[126] In the late 14th century a clerestory and two side aisles were added to the nave.[127]

The so-called Intermediate Church was constructed in 1835–1837.[10][128] It had a square tower, topped with an octagonal spire, and could seat around 1800 worshippers.[129] Its floor level was approximately 1.8 m (6 ft) higher than that of the church it replaced, allowing the base of the medieval nave to become a crypt.[130] In 1868–1877, the Intermediate Church was rebuilt into the present St Martin's Church, designed in the Decorated Gothic style by the architect Henry Woodyer.[131][132] The 64 m (210 ft) spire of the current church was dedicated as a memorial to Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (who had died in 1873)[133] and in 1905–1911 the Lady chapel was added.[132]

In order to accommodate the growing population in the south of the town, a second Anglican church, St Paul's, was opened in 1857 on land donated by Henry Thomas Hope. Designed by the architect, Benjamin Ferrey, it was built of Bath stone in the Decorated Geometric style.[134][135] A daughter church to St Martin's, designed by Edwin Lutyens and dedicated to St Mary, was opened at Pixham in 1903.[136][137]

In the two centuries following the passing of the 1558 Act of Uniformity, many inhabitants of Dorking embraced more extreme forms of protestantism and by 1676, the parish (which had a total population of around 1500) contained 200 nonconformists.[138] In 1620, six residents, including Williams Mullins (a cobbler) and his daughter Priscilla, joined the Mayflower to establish a Separatist colony in the New World.[139][140][141][note 21] During the Civil War, the townsfolk supported the Parliamentarians, but although some of Oliver Cromwell's soldiers were billeted in Dorking, no fighting took place nearby.[144]

Christopher Feake, the Fifth Monarchist and independent minister, lived in the town (allegedly under a false identity) following The Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. He may have incited some of the more radical residents to violence.[138][146] Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe and a committed Presbyterian throughout his life, was educated in Dorking for five years, c. 1669–74. He attended a school in Pixham Lane run by Revd James Fisher a non-conformist who had been ejected as Rector of Fetcham.[146] In 1662 Fisher was involved in establishing Dorking Congregational Church, which by the 1690s was meeting in a barn on Butter Hill in South Street.[147] The present United Reformed Church in West Street, designed by the architect William Hopperton, was built for the group by William Shearburn in 1834.[148]

John Wesley visited Dorking a total of nineteen times between 1764 and 1789.[149] He opened a Methodist chapel in the town in 1777.[150] A new church with a spire was built in South Street in 1900, however this building was sold and demolished in 1974. Since 1973, Dorking Methodists have held services at St Martin's.[151]

Although England had become a predominantly Protestant country during the Reformation, the families of the Earls of Arundel and Dukes of Norfolk remained Catholic.[149] The first Catholic church in Dorking was built in the early 1870s on land owned by the fifteenth Duke of Norfolk, Henry Fitzalan-Howard and was rebuilt into the present St Joseph's Church in the mid-1890s, by the architect Frederick Walters.[152][153]

A mosque was established in Hart Road in 2006. From 1984 the building had been used as a meeting room for the Plymouth Brethren and was a synagogue for a time, before being acquired by the Dorking Muslim Community Association.[154][155]

Dorking in the World Wars

editIn late 1914, Dorking became a garrison town.[156] Empty houses were requisitioned and from January 1915 around 4000 troops were accommodated including those from the London Scottish regiment, the Civil Service Rifles and the Queen's Westminster Rifles.[157] Training took place in the fields to the west and north west of the town.[158] Many local residents were recruited to the Surrey Yeomanry, which (until mid-1915) was stationed at Deepdene House and at the Public Hall in West Street.[159][157] Although he was aged over 40 at the start of the war, the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps, one unit of which was based in the town.[158]

Of the many soldiers from Dorking who died during World War I, the youngest was Valentine Strudwick. He was born in Falkland Road on 14 February 1900 and was educated at St Paul's School. He enlisted in 1915 after concealing his true age and joined the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own). A year later, in January 1916 at the age of 15 years 11 months, he was killed in action at Boezinge, near Ypres. He is buried at Essex Farm Cemetery in Belgium.[160][161]

Empty houses in the town also provided billets for soldiers during World War II and over 3000 school children were evacuated to the Dorking area in September 1939. A local refugee committee (led by Vaughan Williams and the novelist E. M. Forster) was established to find accommodation for refugees fleeing Nazi persecution and also to support long-resident German and Czech nationals in applications to Home Office tribunals to remain at liberty in the UK.[163][164]

At the start of the war, the fortified GHQ Line B was constructed directly to the north of Dorking. This defensive line ran along the North Downs from Farnham via Guildford, before following the River Mole to Horley. The banks of the Mole were fortified with anti-tank obstacles, pillboxes and gun emplacements and an anti-tank ditch was dug from west to east across Bradley Farm (now Denbies Wine Estate). The town itself was a Class "A" nodal point and from August 1940 the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade (part of the VII Corps) was assigned to its defence.[165][166] Pippbrook House (the then offices of the Dorking UDC) became a mobilisation centre and housed an ARP post as well as the local branch of the Women's Voluntary Service.[69]

Over the course of the war, 77 high-explosive bombs and 60 incendiaries were dropped by the Luftwaffe, however only one incident (in October 1940) resulted in fatalities in the town.[163][167]

After the war, at least two Covenanter tanks were buried at Bradley Farm. The first was excavated and restored in 1977 and is now on display at The Tank Museum at Bovington in Dorset.[168] A second was excavated in 2017 for the archaeology programme WW2 Treasure Hunters, presented by the musician Suggs on the TV channel HISTORY. The tank was displayed at the vineyard for six months, before being removed for restoration.[169]

National and local government

editUK parliament

editAs of 2024, Dorking is in the Dorking and Horley parliamentary constituency.

County council

editCouncillors are elected to Surrey County Council every four years. The town is divided between two main wards. The villages to the south east of Dorking are in a third ward:

| First Elected | Member[170] |

Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Hazel Watson[171] | Dorking Hills (includes Pixham and all parts of the town north of West Street, the High Street and Reigate Road)[172] | |

| 2005 | Stephen Cooksey[173] | Dorking South and the Holmwoods (includes the Goodwyns estate and all parts of the town south of West Street, the High Street and Reigate Road)[172] | |

| 2001 | Helyn Clack[174] | Dorking Rural (includes Brockham and other villages southeast of Dorking)[172] | |

District council

editFive councillors represent the town on Mole Valley District Council (the headquarters of which are in Dorking):

| Election | Member[175] |

Ward | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Paul Elderton[176] | Dorking North | |

| 2016 | David Draper[177] | ||

| 1992 | Stephen Cooksey[178] | Dorking South | |

| 2002 | Margaret Cooksey[179] | ||

| 2008 | Tim Loretto[180] | ||

Town council

editDorking does not have a Town Council, however stakeholder engagement in local decision making is conducted through a number of bodies, including the Dorking Town Forum.[181][182]

Twin towns

editDorking is twinned with Gouvieux (Oise, France), Güglingen (Baden-Württemberg, Germany) and Sinalunga (Tuscany, Italy).[183][184]

Demography and housing

editIn the 2011 Census, the combined population of the Dorking North and South wards was 11,158.[1] The larger "built-up area" (which includes the Goodwyns estate, North Holmwood, Pixham and Westhumble, in addition to the two town wards) had a population of 17,741.[2]

| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans/temporary/mobile homes/houseboats | Shared between households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorking North | 378 | 548 | 451 | 465 | 0 | 0 |

| Dorking South | 865 | 695 | 417 | 1,045 | 0 | 3 |

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned with a loan | hectares |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorking North | 4,157 | 1,842 | 34 | 38 | 255 |

| Dorking South | 7,001 | 3,025 | 34 | 32 | 402 |

| Regional average | 35.1 | 32.5 |

Dorking North ward excludes Pixham and Westhumble.[185] Dorking South ward excludes North Holmwood and the Goodwyns estate.[186]

Public services

editUtilities

editUntil the early 18th century, local residents obtained drinking water either directly from the Pipp Brook or from wells. In 1735, a pump was installed to lift water from a spring on the site of Archway Place, which was then distributed via wooden pipes made from bored tree trunks. Local dissatisfaction over the charges levied for the supply, prompted the vestry to reopen a well in the town centre and to install a hand pump there in 1780.[note 23] The Archway Place spring became polluted by sewage in the middle of the 19th century and the works closed.[187][188][190]

The Dorking Water Company (DWC) was formally established in 1869, following the passing of the Dorking Water Act 1869.[191] The company dug a 90 m (300 ft) well on Harrow Road East from where water was transferred by a steam-driven pump to a reservoir on Tower Hill.[192][note 24] In 1902, a new pumping station was built on Station Road and, in 1919, the old one was converted to housing. The second pumphouse was replaced by a new works with boreholes on Beech Close in 1939.[192] The DWC was absorbed by East Surrey Water in 1959.[194]

The Local Board of Health created the first sewerage system in Dorking and opened the treatment works at Pixham on the River Mole in 1888. Four years later, some 1360 houses (around 92% of the town) had been connected, necessitating an extensive rebuilding of the works in 1893.[67] The sewerage system became the responsibility of the Thames Water Authority under the Water Act 1989.

The town gasworks were built in 1834[190] by the Dorking Gas Light Company to supply gas for street lighting. From 1849, the coal required was delivered by train to Dorking West station and then transferred to the works by horse-drawn vehicle. The company was merged with that of Redhill in 1928 and became part of the East Surrey Gas Company when the industry was nationalised in 1948. After gas production ceased in 1956, the site of the works became part of the Dorking Business Park on Station Road.[194][195]

An electricity generating station was opened in 1903 in Station Road, close to the town gasworks. Initially it was capable of generating 180 kW of power, but by the time of its closure in 1939, its installed capacity was 1 MW.[196] Under the Electricity (Supply) Act 1926, Dorking was connected to the National Grid, initially to a 33 kV supply ring, which linked the town to Croydon, Epsom, Leatherhead and Reigate. In 1939, the ring was connected to the Wimbledon-Woking main via a 132 kV substation at Leatherhead.[197][195]

Emergency services and justice

editA nightly patrol was established in Dorking in 1825 and in 1838 a small police force, initially with just three officers, was established under the Lighting and Watching Act 1833.[198] This force became part of the Surrey Constabulary on its creation in 1851.[199] A combined police station and magistrates' court complex was opened at the east end of the High Street in 1894 and the police station relocated to Moores Road in 1938.[200] Purpose-built magistrates courts were opened adjacent to Pippbrook House in 1979[201] and closed in 2010.

A volunteer fire brigade was formed in 1870. Initially based at South Street, it moved to the Public Hall at the west end of West Street in 1881.[200] The brigade became full time in 1912 and, in 1971, it moved to a new fire station adjacent to the newly built ambulance station at North Holmwood.[202] In 2021, the fire authority for Dorking is Surrey County Council and the statutory fire service is Surrey Fire and Rescue Service.[203] Dorking Ambulance Station is run by the South East Coast Ambulance Service.[204]

Healthcare

editDorking Cottage Hospital, opened in 1871 in South Terrace, was the first hospital in the town.[61][205] It was merged in 1948 with the adjacent County Hospital, which had evolved from the Union Workhouse and Poor Law Infirmary, to form Dorking General Hospital.[206] Since 2004, Dorking Hospital has been run as a community hospital by a consortium of local GP groups that provides Outpatient Services for the local area.[207] The nearest accident & emergency departments are at Epsom Hospital (7 mi (11 km)) and East Surrey Hospital (7 mi (11 km)).[208] As of 2020, there are GP practices on Reigate Road and South Street.[209]

Transport

editRoads

editThe A24 London-Worthing and the A25 Guildford-Sevenoaks roads intersect at Deepdene Roundabout on the eastern side of Dorking. The one-way system in the town centre was introduced in 1968.[210]

Railways

editThe Epsom-Horsham and Guildford-Reigate railway lines cross to the northeast of Dorking, but there is now no physical connection between the two.[84] The town is served by three railway stations. Dorking station is managed by Southern and is served by trains to London Victoria via Sutton, to London Waterloo via Wimbledon and to Horsham.[211] Dorking Deepdene and Dorking West stations are managed by Great Western Railway and are served by trains to Reading via Guildford and to Gatwick Airport via Redhill.[212][213]

Buses

editRoute 32 from Dorking to Guildford via Shere and to Redhill via Earlswood is run by Compass Bus.[214] Route 93 from Dorking to Horsham via Goodwyns and Holmwood Park is run by Metrobus on behalf of Surrey County Council.[215] Route 465 from Dorking to Kingston upon Thames via Leatherhead is run by London United.[216] Routes 21 (Epsom – Dorking – Crawley) and 22 (Shere – Dorking – Crawley) are run by Metrobus.[217]

Cycle routes

editNational Cycle Route 22 passes through the town centre[218] and the Surrey Cycleway runs to the east.[219]

Long distance footpaths

editThe Greensand Way, a 108 mi (174 km) long-distance footpath from Haslemere, Surrey to Hamstreet, Kent, passes through the south of Dorking.[220] The route approaches the town centre from the east, passing over The Nower, then crossing the junction between South Street and Horsham Road. It climbs through the Glory Wood, before crossing Deepdene Terrace.[221] The North Downs Way, between Farnham and Dover, passes approximately 1,000 yd (1 km) to the north of Dorking.[222] Dorking station is the southern terminus of the Mole Gap Trail, which starts at Leatherhead station.[223]

Education

editPrimary schools

editThere are five primary schools in Dorking, the oldest of which is Powell Corderoy School. It was founded in 1816 as The Dorking British School, and its original premises were in West Street; but twenty years later it moved to North Street. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the school had expanded and the funds for a new building in Norfolk Road were raised by Edith Corderoy and Mr T. Powell. The new site was opened in 1898 and the school adopted its present name in 1906.[200][224] The school moved to its current location in Longfield Road in 1968.[224]

St Martin's Primary School was founded as a National School by the vestry in the 1830s,[225] however there is thought to have been a school located in the transepts of the parish church as early as the 17th century.[226] The National School was moved from the grounds of the church to West Street in 1862.[226] The Middle School relocated to Ranmore Road in 1969 and was joined by the First School in 1985.[227] The Pixham First School was founded in 1880 by Mary Mayo and was built to a design by Gilbert Redgrave.[228] St Paul's Primary School was founded in 1860.[229][230]

St Paul's School was designed by the architect, Thomas Allom, and admitted its first pupils in March 1860.[231] The infants department opened in 1872 and, from that year, the school educated children aged from 5 to 13.[232] Today, St Paul's is a Church of England Voluntary Aided Primary School and educates children from the ages of 5 to 11.[233]

St Joseph's Catholic Primary School was founded in 1873 by Augusta Fitzalan-Howard, Duchess of Norfolk. The first premises were in Falkland Grove adjacent to St Joseph's Church. The school was run by nuns of the Servite Order from 1887 to 1970, when it moved to its present site in Norfolk Road, which had been vacated by Powell Corderoy School.[234]

St John's Primary School was founded in 1955 on the Goodwyns housing estate to the south of the town.[227] It was known as The Redlands Junior School until August 1999.[235]

New Lodge School, a private prep school formed in 2002 from the merger of Stanway School and Nower Lodge School, closed in 2007.[236][237]

Secondary schools

editThe Ashcombe School is a coeducational secondary school, north of the town centre. It traces its origins to the Dorking High School for Boys, founded in 1884, and the St Martin's High School for Girls, opened in 1903.[200] In 1931, the two schools were merged to become the Dorking County School and moved to a new site in Ashcombe Road. In 1959 the Mowbray County Secondary Modern for girls was opened on an adjacent site. The two schools were combined to create the Ashcombe School in 1975.[227]

The Priory School opened as the County Secondary Modern Mixed School in September 1949. It was initially based at the Dene Street Institute, but moved to its present location in West Bank within a few years. In 1959, the girls were transferred to the Mowbray School in the Ashcombe Road, and Sondes Place continued as a boys-only school.[238] In 1976 it became a mixed comprehensive school and was renamed the Priory School in 1996.[239]

Culture

editArt

editThe Dorking Group of Artists, established in 1947, exhibits locally twice a year, in Betchworth and at Denbies.[240] The Arts Society Dorking promotes local art appreciation and the preservation of the town's artistic heritage.[241]

Leith Hill Musical Festival

editThe three-day Leith Hill Musical Festival for local, amateur choral societies, founded in 1905, takes place at the Dorking Halls each year. Ralph Vaughan Williams was the Festival Conductor until 1953, a post currently held by Jonathan Willcocks.[242][243]

Each day features a different group (or division) of choirs, which compete against each other in the morning and then combine to give a concert in the evening. Following the tradition established by Vaughan Williams, the Messiah by Handel and the St Matthew and St John Passions by J. S. Bach are frequently performed.[242][244]

After the death of Vaughan Williams in 1958, the festival committee commissioned David McFall to design a bronze bas relief likeness of the composer: one cast was placed in St Martin's Church and another in the Dorking Halls.[245]

Recording studios

editStrawberry Studios South was opened in 1976, in a former cinema in South Street, by Graham Gouldman and Eric Stewart of the band 10cc. They recorded the album, Deceptive Bends there. Other artists also worked at the Studios, including Paul McCartney, who recorded part of "Ebony and Ivory" (a duet with Stevie Wonder) there.[246] The English rock band, The Cure, recorded at Rhino Studios at Pippbrook Mill.[247]

Literature

editThe Battle of Dorking, a novella written by Lt. Col. Sir George Tomkyns Chesney in 1871, was set in the town. Describing a fictional invasion and conquest of Britain by a German-speaking country, it triggered an explosion of what came to be known as invasion literature.[248][249] Benjamin Disraeli wrote part of his political novel Coningsby while staying at Deepdene between 1841 and 1844. The novel was subsequently dedicated to his host, Henry Thomas Hope.[60][250] The fourth chapter of A Fool's Alphabet by novelist Sebastian Faulks, published in 1992, is set in the town.[251]

Sport

editShrove Tuesday football

editA football game was played annually in Dorking on Shrove Tuesday between two teams representing the eastern and western halves of the town. The match began at 2pm outside the gates to St Martin's Church and lasted until 6pm.[252] After a particularly riotous game in 1897,[253] the local magistrates declared that the tradition was in breach of the Highway Act 1835 and 50 participants were fined.[254] Arrests were also made after local townsfolk attempted to stage the match in 1898, 1899 and 1903.[255][256][257] The local newspaper declared the custom extinct in 1907.[258]

Association football

editDorking F.C. was formed in 1880 and moved to Meadowbank in 1956.[259][260] The stadium was condemned as unsafe in 2013 and for the next three years, the club shared grounds, first at Horley and then Westhumble.[261][262] Dorking F.C. closed in 2017.[263][264]

Dorking Wanderers F.C. was founded in 1999. The team played its home games at Westhumble for ten seasons from 2007, before moving to the refurbished Meadowbank Stadium in July 2018.[265][266]

Rugby

editDorking rugby football club was founded in 1921. Initially its home matches were played at Meadowbank, but it moved the following year to Pixham. In 1972 the club relocated to the Big Field at Brockham[267] as tenants of the National Trust, which had acquired the field in 1966.[268] In the 2019–20 season, the 1st XV played in the London and South East Premier division.[269] Notable former players include Elliot Daly, George Kruis and Kay Wilson.[267]

Motor racing

editRob Walker's privateer racing team was based at Pippbrook Garage in London Road from 1947 to 1970. The team won nine Grands Prix and their drivers included Stirling Moss (1958–1961) and Graham Hill (1970).[270] Walker's contribution to motorsport and to Dorking was celebrated on the centenary of his birth in October 2018 with a parade of classic cars through the town centre.[271]

Cycling

editDorking Cycling Club was founded in 1877[272] and by the 1890s was organising camps for amateur cyclists from across the south east of England.[273] The club was refounded in 2011 and organises a programme of weekly rides for members.[272] The 2012 Summer Olympic cycling road races passed through Dorking en route to Box Hill.[274][note 25][note 26]

Running

editDorking and Mole Valley Athletics Club is based at Pixham Sports Ground. They host the annual Dorking Ten road race starting from Brockham Green.[281]

The weekly Mole Valley Parkrun has taken place at Denbies Wine Estate since March 2018.[282][283] The vineyard also hosts the annual Run Bacchus marathon.[284] The annual UK Wife-Carrying Race[285] takes place at The Nower.[286][287]

Tourist attractions

editDenbies Wine Estate

editDenbies Wine Estate, to the north of Dorking, is one of the largest wine producers in the UK. The vineyard, which covers some 107 ha (260 acres), was first planted in 1986 on the site of Bradley Farm, part of the Denbies estate. The winery and visitor centre were opened in 1993.[288][289]

Dorking Museum

editDorking Museum was opened in West Street in January 1976.[290] The building had previously been an iron foundry, which had opened in the 1820s and closed after World War II.[291] The museum houses a wide range of historical artefacts, as well as fossils and mineral samples from the Dorking area.[292] Permanent displays explain the history of the town from prehistoric times to the present day,[293] and the building also hosts temporary exhibitions, often connected with significant anniversaries of events such as World War I.[294][295]

The museum was fully refurbished between 2008 and 2012[293] and was short-listed for the Museums Heritage Awards in 2013.[296]

South Street Caves

editThe caves in South Street are thought to have been excavated in four distinct phases. Firstly, three wells, the largest of which has the date 1672 inscribed on its wall, were sunk vertically from Butter Hill above. The upper level, a network of four caverns which intersects the wells, was dug in the late 17th or early 18th centuries. These caves are linked by a staircase to the lowest level, a circular chamber which may have been used by religious dissenters, approximately 20 m (70 ft) below ground level. In Victorian times, the larger caverns were adapted for use as wine cellars. The current entrance to the caves dates from 1921.[107]

The South Street caves were sold to Dorking UDC in 1921 and were leased by the council to various local wine merchants until the 1960s. The Dorking and Leith Hill Preservation Society first opened the caves for public tours in the 1970s.[104] Dorking Museum assumed responsibility for running tours in May 2015. Prince Edward visited the caves in March of the same year.[104][297]

Other nearby attractions

editSeveral National Trust properties are close to Dorking, including Box Hill,[15] Leith Hill,[16] Polesden Lacey[17] and Ranmore Common.[298]

Parks and open spaces

editCotmandene

editCotmandene is a 4.78 ha (10-acre) area of common land to the east of the town centre (the name is thought to mean the heath of the poor cottages).[299][300] During the Middle Ages it was used by commoners to graze pigs.[13] The first almshouses on the north side of Cotmandene were built in 1677[301] and were given endowments in 1718 and 1831. They were rebuilt in 1848 and again in 1961.[65]

Cricket matches were played on the heath during the 18th century and are recorded in Edward Beavan's 1777 poem Box Hill.[302] A painting entitled A Cricket Match on Cotmandene, Dorking by the artist James Canter, dating to around 1770, is now held by the Marylebone Cricket Club.[303] In the 19th century, a funfair took place at the same time as the Ascension Day livestock fair in the town centre.[304] In 1897, to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk (who was lord of the manor of Dorking) gave Cotmandene to the Urban District Council (UDC) on the condition that it was "to remain a perpetual ornament and pleasure to the town".[200]

Deepdene Terrace and Gardens

editDeepdene was a country house to the south-east of Dorking. Its name derives from the narrow natural amphitheatre in the former grounds, most likely formed by erosion of the sandstone hillside by spring water.[60] The gardens were first laid out by Charles Howard in the 1650s and both the diarist, John Evelyn, and John Aubrey recorded visits there in the second half of the 17th century.[305][306] The grounds include a mausoleum in which owners Thomas Hope and Henry Thomas Hope are buried.[60]

In the late 19th century, the property began a period of decline accelerated by the bankruptcy of the owner, Lord Francis Hope, in 1896. Much of the estate was sold for housebuilding in the early 20th century. In 1943, the terrace and garden were purchased by the Dorking and Leith Hill Preservation Society (chaired by Ralph Vaughan Williams) and transferred to the UDC, however the house was demolished in 1969.[60] In the mid-2010s, the garden was restored and was reopened to the public as the "Deepdene Trail".[307][308][309]

Glory Wood

editThe Glory Wood (the highest point in Dorking) is an area of primarily deciduous woodland to the southeast of the town centre. The southern part is known as "Devil's Den" and contains mainly oak with an area of coppiced sweet chestnut.[310]

The Glory Wood was promised to the town in 1927 by Lord Francis Hope, on the condition that it was not to be built upon.[311] The land was to have been transferred to the UDC in July 1929, however Hope withheld the gift until 1934, in protest at the published route of the Dorking Bypass through the Deepdene estate.[312][313]

Meadowbank

editMeadowbank is a park on the north side of the Pipp Brook. In medieval times, it was part of the lordship lands and later became part of the Denbies estate. By the start of the 20th century, it was the grounds of large private house (also called "Meadowbank"). The house and grounds were purchased by Dorking UDC in 1926, with the intention of building 150 council houses, however owing to financial constraints, the Council instead decided to sell the western third for development. The Parkway estate was completed in 1935.[202]

The park was landscaped in the decade before World War II and included the Pippbrook Mill mill pond, which was given to the town in 1934. From 1954, Meadowbank became the permanent home of Dorking Football Club until 2014.[261][314] Dorking Wanderers F.C. moved to the refurbished ground in 2018.[315]

The Nower

editThe Nower is an area of open grassland, which rises above Dorking to the west of the town centre. Together with the adjacent Milton Heath, it forms a 16 ha (40-acre) nature reserve owned by Mole Valley District Council[310] and is managed by Surrey Wildlife Trust.[316]

The Nower was given to the town in 1931 by Charles Barclay, the owner of the Bury Hill estate,[317][318] although it had been accessible to visitors since Victorian times. Views over Dorking may be enjoyed from "The Temple", which dates from the early 19th century.

Notable buildings and landmarks

editDorking Cemetery

editDorking Cemetery was opened in 1855 on farmland that had been purchased from the Deepdene estate.[319] Two chapels were built for funeral services, one for Anglicans (with a rectangular floor plan) and one (with an octagonal floor plan) for non-conformists. Both were designed by Henry Clutton and were constructed from flint with stone dressings.[320][321] An entrance lodge on Reigate Road was also provided.[322] Originally the area of the cemetery was 1.6 ha (4 acres), but was enlarged to 5.7 ha (10 acres) between 1884 and 1923.[319]

The English novelist George Meredith[323] and Victoria Cross recipient Charles Graham Robertson[324] are among those buried there. The cemetery also contains 61 Commonwealth war graves of military personnel from the First and Second World Wars.[325]

Dorking Halls

editThe Art Deco Dorking Halls building, designed by the architect Percy W. Meredith for the Leith Hill Musical Festival (LHMF), was opened in 1931. The Grand Hall was intended to be used for performances of the Passions by J. S. Bach, but two smaller halls (the Masonic and Martineau) were also constructed as part of the same complex. During World War II, the building was used by the Meat Marketing Board and the Army, and it was then sold to Dorking UDC. A major refurbishment was undertaken by Mole Valley District Council between 1994 and 1997.[326] The Martineau Hall houses the Premier Cinema.[327][note 27]

Pippbrook House

editPippbrook House, a Gothic country house to the north east of the town centre, was designed as a private residence for William Henry Forman by George Gilbert Scott in 1856.[68][note 28] The house and surrounding 2.3 ha (5.7 acres) were bought by the UDC in December 1930, for use as administrative offices.[333] The UDC's successor, MVDC, opened purpose-built offices in the grounds in 1984, which enabled the local public library to move into the space vacated. The library relocated to St Martin's Walk in the town centre in 2012.[68] In 2020, MVDC announced plans to develop Pippbrook House as a "community hub and start-up business centre".[334]

White Horse Hotel

editThe first building to be recorded on the site of the White Horse Hotel was granted to the Knights Templar by John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey, in around 1287.[335] When the Templars were suppressed in 1308 by order of Pope Clement V, the property was confiscated and passed to the Knights of the Order of St John. For much of the late medieval period, it was known as the "Cross House" and in the 16th century it was the residence of the parish priest.[336]

The property became an inn around 1750 (by which time it was known as "The White Horse"), a few years before the opening of the Epsom to Horsham turnpike road.[336] Most of the current hotel was built during the 18th century (including the timber-framed frontage which faces the High Street), however some parts date from the 15th and 16th centuries.[337] Famous guests have included Charles Dickens who wrote his novel The Pickwick Papers, whilst resident in the mid-1830s.[338] Further additions were made to the hotel in the 19th century, which is protected today by a Grade II listing.[337]

Statues and sculptures

editThe galvanised metal sculpture of a Dorking cockerel by the artist Peter Parkinson was erected on the Deepdene roundabout in 2007. The 3 m-tall (10 ft) statue pays homage to the historical importance of the town's poultry market.[340] The cockerel is a frequent target of yarn bombing and can be seen dressed in hats, scarves and other items of clothing.[341][342]

The two statues outside the Dorking Halls were designed by William Fawke. The statue of architect and master builder Thomas Cubitt was installed in 1995. The statue of Ralph Vaughan Williams was donated by Sir Adrian White and was unveiled in 2001.[326]

The sculpture of two cyclists at the Pixham End roundabout was unveiled in July 2012, less than two weeks before the Olympic road race events were routed through Dorking. The installation was designed by the artist Heather Burrell, and just over half of the cost was donated by members of the public, each of whom is represented by an oak leaf on either the cyclists' torsos or the bicycle wheels.[343]

There are two sculptures by the artist Lucy Quinnell in the town: the first, a metal arch commemorating the writer and philosopher Grant Allen, was installed at the entrance to Allen Court in 2013;[344] the second, depicting the Mayflower sailing westwards towards the New World, was commissioned by Mole Valley District Council and was unveiled in West Street in 2021.[345]

War memorial

editThe town war memorial, in South Street, was dedicated in 1921 "in memory of Dorking men who fell in the Great War". Designed by the architect Thomas Braddock, it was constructed from dressed Portland stone. The memorial was modified in 1945 to commemorate those who had died in World War II, with the addition of the wings at each side. At the base, a verse from 1 Samuel is inscribed: "They were a wall unto us both by night and by day."[346][347] The names of 264 people who died in the two conflicts (both military personnel and civilians) are recorded, including seven women.[348] The memorial is protected by a Grade II listing.[346][note 29]

Notable residents

editThree former residents of Dorking have been awarded the Victoria Cross (VC):

- Sir William Leslie de la Poer Beresford was given his VC for rescuing a comrade at Ulundi (now in South Africa) during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. After retiring from the army, he lived at the Deepdene with his wife, the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough.[351][352]

- Sir Lewis Halliday was awarded the VC for repelling an enemy attack during the 1899-1901 Boxer Rebellion in China. He died in Dorking in 1966.[353][354]

- Charles Graham Robertson was given his VC for repelling an enemy attack during the German spring offensive in March 1918. On his return to Dorking after the war, he was honoured with a parade and the presentation of a gold watch. He continued to live in the town until his death in 1954 and is buried in the cemetery.[324][355]

People born in the town include:

- Walter Dendy Sadler (1854–1923), artist and painter.[356]

- Laurence Olivier (1907–1989), actor and director. A blue plaque marking his birthplace can be found in Wathen Road.[357][358]

- Jamie Mackie (born 1985) former Scotland international football player.[359]

- Peter George (1943–2007) former chairman and chief executive of Hilton Group Plc.[360]

People who have lived in the town include:

- Daniel Defoe (c.1660–1731), who attended Rev. James Fisher's boarding school in Pixham Lane, and later mentioned Dorking in his Tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain.[146]

- Peter Labilliere (1725–1800), a former Army Major and political agitator lived in a cottage on Butter Hill from 1789.[361][362] In accordance with his wishes he was buried head downwards 11 June 1800 on the western side of Box Hill.[363]

- The composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958) lived in Dorking from 1929 to 1951.[364] One of his most famous works, The Lark Ascending, was inspired by a poem of the same name published in 1881 by the author George Meredith, who lived at Box Hill.[365]

- Composer David Moule-Evans (1905–1988)[366] collaborated with Vaughan Williams on the pageant play England's Pleasant Land, written by E.M. Forster, which was first performed in Dorking in 1938.[367]

- Absolute Radio DJ Christian O'Connell lived in Dorking for several years until 2018.[368]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ No evidence of Iron Age settlement activity has been found in the town centre, however the nearby hillforts at Anstiebury (Leith Hill)[39][40] and Holmbury Hill[41][42] date from the first century BC.[43] Traces of an Iron Age field system and settlement activity have been observed on Mickleham Downs (about 2 mi (3 km) northeast of Dorking).[44][45]

- ^ The hoard was discovered by a ploughman working at Winterfold Hanger. The coins were contained in a fragile wooden box, buried 25–30 cm (10–12 in) beneath the ground. The find included pennies from the reigns of Æthelwulf of Wessex (839–858), Æthelberht of Wessex (860–866), Beornwulf of Mercia (823–826), Burgred of Mercia (852–874) and several other monarchs. Around a third of the coins were donated to the British Museum.[52][53]

- ^ Similarly, in 1448 Sir Thomas Browne, Sheriff of Kent, purchased the manor of West Betchworth, which included Betchworth Castle. Browne converted the castle into a fortified house, in which his family and their descendants lived until the 1830s, when it was bought by Henry Thomas Hope and added to the Deepdene estate.[61] Hope dismantled much of the castle (which was in a poor state of repair) leaving the ruins visible today.[60] The remains are protected by a Grade II listing.[62]

- ^ The Dorking Union was responsible in for poor relief in the parish of Dorking (which included Holmwood, Westcott and Coldharbour) and also the parishes of Abinger, Capel, Effingham, Mickleham, Newdigate, Ockley and Wootton.[65]

- ^ Pippbrook House is a Grade II*-listed building.[68]

- ^ In the late 17th century the Burford Bridge was a footbridge and wheeled traffic was required to cross the Mole via the adjacent ford.[72]

- ^ Much of this "Winter Road" route is now Box Hill Road and the B2032.

- ^ The route of the road across Holmwood Common was later altered and other improvements were made under the Horsham and Dorking Turnpike Road Act of 1858. Turnpikes south from Horsham to Steyning and Worthing were constructed in 1764 and 1802 respectively.[77]

- ^ Tollhouses were provided at "Giles Green" (close to the intersection of the A24 and the North Downs Way) and at the "Harrow Gate" (close to the junction of the A2003 and Hampstead Road). In 1857, the "Harrow Gate" tollhouse was moved further south to Flint Hill. Its approximate position is the present-day junction between Tollgate Road and the A2003.[77]

- ^ Dorking Deepdene station was originally named "Box Hill and Leatherhead Road".[83]

- ^ In 1923 the Southern Railway proposed a north-east spur to link the town's two railway lines. The necessary land was purchased and parliamentary approval was obtained, but no construction work took place.[84]

- ^ Electrification was extended to Horsham in 1938.[87]

- ^ Two Dorking cockerels, representing the town, appear as supporters on the Mole Valley District Council coat of arms either side of the escutcheon.[95]

- ^ The market house was demolished in 1813.[96]

- ^ The Dorking Poultry Society was founded in 1867 and held an annual competition for local breeders.[99]

- ^ Chalk (calcium carbonate) must be heated above 825 °C (1,517 °F) to convert it to quicklime (calcium oxide).[101]

- ^ The antiquarian J.S. Bright, writing in 1884, claimed that Dorking produced "some of the best lime in England" and that it was used in the construction of Somerset House, the Bank of England, London Bridge and the Palace of Westminster.[103]

- ^ Although the Dorking programme was locally funded, practicalities were arranged under the Petworth Emigration Scheme which was responsible for enabling a total of 1800 people from rural towns across south east England to travel to and settle in Canada.[110][111]

- ^ An additional 16 residents, who were not in receipt of poor relief and who were able to pay for their own passage, also joined the group. In total 77 Dorking residents left England for Canada in 1832, with a further 13 from Capel.[108]

- ^ The Fraser Gardens estate was named after Sir Malcolm Fraser of Pixham, who donated the funds to purchase the land from the Denbies estate.[118][119]

- ^ William Mullins, his wife Alice, daughter Priscilla and son Joseph lived at 58–61 West Street with their apprentice, Robert Carter. All five travelled together on the Mayflower.[139][142] Mullins' house is the only surviving home of a Pilgrim Father in England.[143] The sixth Dorking resident to join the Pilgrims was Peter Browne.[142]

- ^ The Old Pumphouse dates from the early 19th century. It is built on the site of the first water pumping station in Dorking, which supplied fresh water to the town from the Pipp Brook. The new building includes the original cellar, which still contains part of one of the original pumps. The Grade II listed building bears a plaque, inscribed "R. P. Waterworks erected 1738". The initials 'R. P.' reference Resta Patching junior, the son of a prominent Dorking Quaker, who was responsible for the scheme.[187][188][189]

- ^ The location of the hand pump in the town centre, installed in 1780, is unclear, but it thought to be at Pump Corner at the intersection of the High Street, West Street and South Street.[187]

- ^ In the 1880s there was a proposal to supply seawater to the town from a conduit between Lancing and London.[193]

- ^ The torch relays for the 1948 and 2012 Olympic games passed through Dorking.[275]

- ^ The London–Surrey Cycle Classic was a test event which took place in summer 2011 along the same course as the 2012 Olympic cycling road race.[276] Between 2013 and 2019, the London–Surrey Classic and RideLondon-Surrey Classic (for professional and amateur cyclists respectively), were also routed through the town.[277] Both events were cancelled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic[278] and in the same year, Surrey County Council decided not to support running the events after 2021.[279][280]

- ^ There have been a number of cinemas in the town. The first to open (in 1910) was the Cinema Royal in the High Street, but it closed after WWI. The building is now used by The Salvation Army.[328] The Royal Electric Cinema (later the New Electric and then the Regent) opened in 1913 and closed in 1938.[328][329] The Pavillion, also in South Street, opened in 1925 and closed in 1963.[328][329] The Playhouse, at the Public Hall in West Street, showed silent films from 1913 to 1930.[328] The largest cinema was the Embassy on Reigate Road, opposite the Dorking Halls, which opened as the Gaumont in 1938. After closure in 1973, it served as a meeting hall for Jehovah's Witnesses until its demolition in 1983.[328][329]

- ^ The first recorded owners of the Pippbrook estate were Walter and Alicia atte Pyppe in 1378. The first substantial house was built in 1758 by William Page of Tower Hill, who lived there for six years. Between 1764 and 1817, there were a further ten owners, of which the last was Henry Pigot, a general in the British Army.[330] The house was then bought by William Crawford, on whose death in 1843 it passed to his son, Robert Wigram Crawford.[331] Thomas Seaton Forman purchased the property in 1849, but died just over a year later and it was inherited by his brother, William Henry Forman, who commissioned the current building.[332]

- ^ The construction of the War Memorial was part of a larger improvement scheme to widen South Street. A bandstand was built adjacent to the Memorial, paid for by private funds. Increasing traffic noise had however rendered it unusable by the Town Band by the 1930s[210] and it was demolished in the 1960s.[349] The dedication plaque is preserved at Dorking Museum.[350]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Key Statistics; Quick Statistics: Population Density Archived 11 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine 2011 United Kingdom census, Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 December 2013

- ^ a b UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Dorking Built-up area sub division (1119884849)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Briggs, Rob (2018). "Dorking, Surrey". Journal of the English Place-Name Society. 50: 17–54. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Surrey Domesday Book". Archived from the original on 15 July 2007.

- ^ Ekwall 1940, p. 142

- ^ Gover, Mawer & Stenton 1934, pp. 269–270

- ^ Crocker 1990, p. 20

- ^ Bright 1884, p. 11

- ^ a b Historic England. "Bowl barrow in The Glory Wood (1007881)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robertson, Jane (August 2004) [2002]. "Extensive Urban Survey of Surrey: Dorking" (PDF). Surrey County Archaeological Unit. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ a b Bright 1884, p. 13

- ^ a b c d Ettinger, Jackson & Overell 1991, pp. 15–16

- ^ a b c d e Ettinger, Jackson & Overell 1991, pp. 11–13

- ^ "Surrey Interactive Map". Surrey County Council. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Box Hill". National Trust. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Leith Hill Tower and Countryside". National Trust. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Polesden Lacey". National Trust. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021..

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 11–13

- ^ Gallois & Edmunds 1965, pp. 35–40

- ^ Gallois & Edmunds 1965, pp. 51–53

- ^ Gallois & Edmunds 1965, pp. 74–77

- ^ Gallois & Edmunds 1965, pp. 71–72

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 47–51

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 58–59

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 73–74

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 80–82

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 84–87

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, pp. 97–99

- ^ Kennedy, William James (1969). "The correlation of the Lower Chalk of south-east England". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 80 (4): 459–560. Bibcode:1969PrGA...80..459K. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(69)80033-7.

- ^ Dines et al. 1933, p. 118

- ^ a b "Land at rear of 72–82 South Street, Dorking". Surrey Archaeological Society. 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Land at rear of 72–82 South Street, Dorking". Surrey Archaeological Society. 2012. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Waitrose, South Street, Dorking". Surrey Archaeological Society. 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ a b "A Bronze Age ring-ditch discovered at Waitrose site, Dorking". Surrey County Council. 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ "An Exciting Excavation in South Street, Dorking". Exploring Surrey's Past. 2016. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Bowl barrow on Milton Heath (1007882)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Bowl barrow on Box Hill, 250m north-west of Boxhurst (1007888)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Bowl barrow on Box Hill, 230m west of Upper Farm Bungalow (1007889)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Historic England. "Anstiebury Camp: a large multivallate hillfort south-east of Crockers Farm (1007891)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Hayman, H (2008). "Archaeological excavations at Anstiebury Camp hillfort, Coldharbour, in 1989 and 1991" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 94: 191–207. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Holmbury Camp: a small multivallate hillfort north of Three Mile Road (1013183)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Hooker, R; English, J (2008). "Holmbury Hillfort: An archaeological survey". Surrey Archaeological Society. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Thomas, MS (2010). "A re-contextualisation of the prehistoric pottery from the Surrey hillforts of Hascombe, Holmbury and Anstiebury" (PDF). Surrey Archaeological Collections. 95: 1–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Salkeld, E (28 February 2020). "Having a field day with Lidar in the Surrey HER". Exploring Surrey's Past. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Hogg, I (2019). "Activity within the prehistoric landscape of the Surrey chalk downland, Cherkley Court, Leatherhead". Surrey Archaeological Collections. 102: 103–129.